A training program was developed to increase general practitioners' engagement in the optimal management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH). The goal of this study was to evaluate changes in BPH management after the implementation of a training program.

Material and MethodsThis observational retrospective cohort study was conducted between 2019 and 2020. Aggregated data were analyzed in three evaluation periods (2010, 2012 and 2015), addressing quality indicators for diagnosis, treatment, and treatment outcomes.

ResultsOverall, 118 795 patients who presented any data points were included. All quality indicators (number of IPSS and PSA determinations) increased between the first period and the last. Combination (α-blocker + 5-ARI) therapy was increasingly prescribed during the study periods whereas the proportion of prescriptions for single-agent α-blocker showed no significant differences among the periods analyzed. However, the total number of patients eligible for combination therapy who actually received this treatment was low in all periods (7.5%, 17.9%, and 20.1%, in 2010, 2012, and 2015, respectively). The outcome indicators revealed a decrease in referrals to the urology unit mostly among newly diagnosed patients. Even though the proportion of patients who underwent BPH-related surgeries increased significantly from the first to the second period, the number of surgeries remained stable between the second and third periods.

ConclusionsThe training program had a generally positive impact on the management of BPH patients in PC, but the overall study period may be insufficient to show an effect on some outcome indicators such as the number of surgeries.

Se desarrolló un programa de formación para fomentar la implicación de los médicos de atención primaria (AP) en el manejo óptimo de la hiperplasia benigna de próstata (HBP). El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar los cambios en el manejo de la HBP tras la implementación de un programa de formación.

Material y métodosEste estudio observacional retrospectivo de cohortes se llevó a cabo entre 2019 y 2020. Los datos agregados se analizaron en tres períodos de evaluación (2010, 2012 y 2015), abordando indicadores de calidad para el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y los resultados del tratamiento.

ResultadosEn total, se incluyeron 118.795 pacientes. Todos los indicadores de calidad (valores de IPSS y PSA) aumentaron entre el primer periodo y el último. El número de prescripciones de tratamiento combinado (α-bloqueante + 5-ARI) aumentó a lo largo de los periodos de estudio, y la proporción de prescripciones de α-bloqueante en monoterapia no mostró diferencias significativas entre los periodos analizados. Sin embargo, el número total de pacientes elegibles para terapia combinada que recibieron este tratamiento fue bajo en todos los períodos (7,5%, 17,9% y 20,1%, en 2010, 2012 y 2015, respectivamente). Los indicadores de resultados revelaron una disminución de las derivaciones a Urología, principalmente entre los pacientes recién diagnosticados. Aunque la proporción de pacientes que se sometieron a cirugía relacionada con la HBP aumentó significativamente del primer al segundo periodo, el número de cirugías se mantuvo estable entre el segundo y el tercer periodo.

ConclusionesEl programa de formación tuvo un impacto altamente positivo en el manejo de los pacientes con HBP en AP, pero el periodo total del estudio puede no ser suficiente para reflejar los efectos sobre algunos indicadores de resultados, como por ejemplo el número de cirugías.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a prevalent disease among aging males.1,2 Clinical BPH is a chronic disease defined as a non-malignant prostate overgrowth that often causes the obstruction of the urethral flow and other manifestations characterized as lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).1,3 BPH is classified according to LUTS severity.4,5 These symptoms affect the quality of life (QoL) of 43% of men >60 in Spain.6 However, the QoL of patients with moderate-severe symptoms improves with the use of medical treatments available in real-life practice, thus highlighting the importance of continued care in these patients.7

According to guideline recommendations, the current diagnosis of patients with LUTS suggestive of BPH involves a general anamnesis, completion of a validated symptom score questionnaire, evaluation of LUTS severity, physical examination, and the assessment of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) values.8–10 All these procedures are available in primary care (PC), and general practitioners (GPs) can be trained to perform them.2,11 Increasing the involvement of GPs in the management of these patients would impact positively on the maintenance of their QoL and reduce healthcare costs.

For these reasons, a training program (TP) was developed with the agreement of the main Urology and PC societies of Spain to improve GPs’ skills in the management of BPH patients. This program aimed to provide guidance to GPs at two levels: first, addressing the specific management of outpatients with a diagnosis suggestive of LUTS, and second, focusing on the management of patients with a confirmed diagnostic of BPH.12

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of the TP imparted to GPs in the Valencian Community on the optimal management of BPH patients, through the evaluation of a set of quality-of-care indicators addressing diagnosis, treatment, and use of resources.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis was an observational, retrospective, aggregate cohort study conducted in the Valencian Community, Spain, between October 2019 and February 2020.

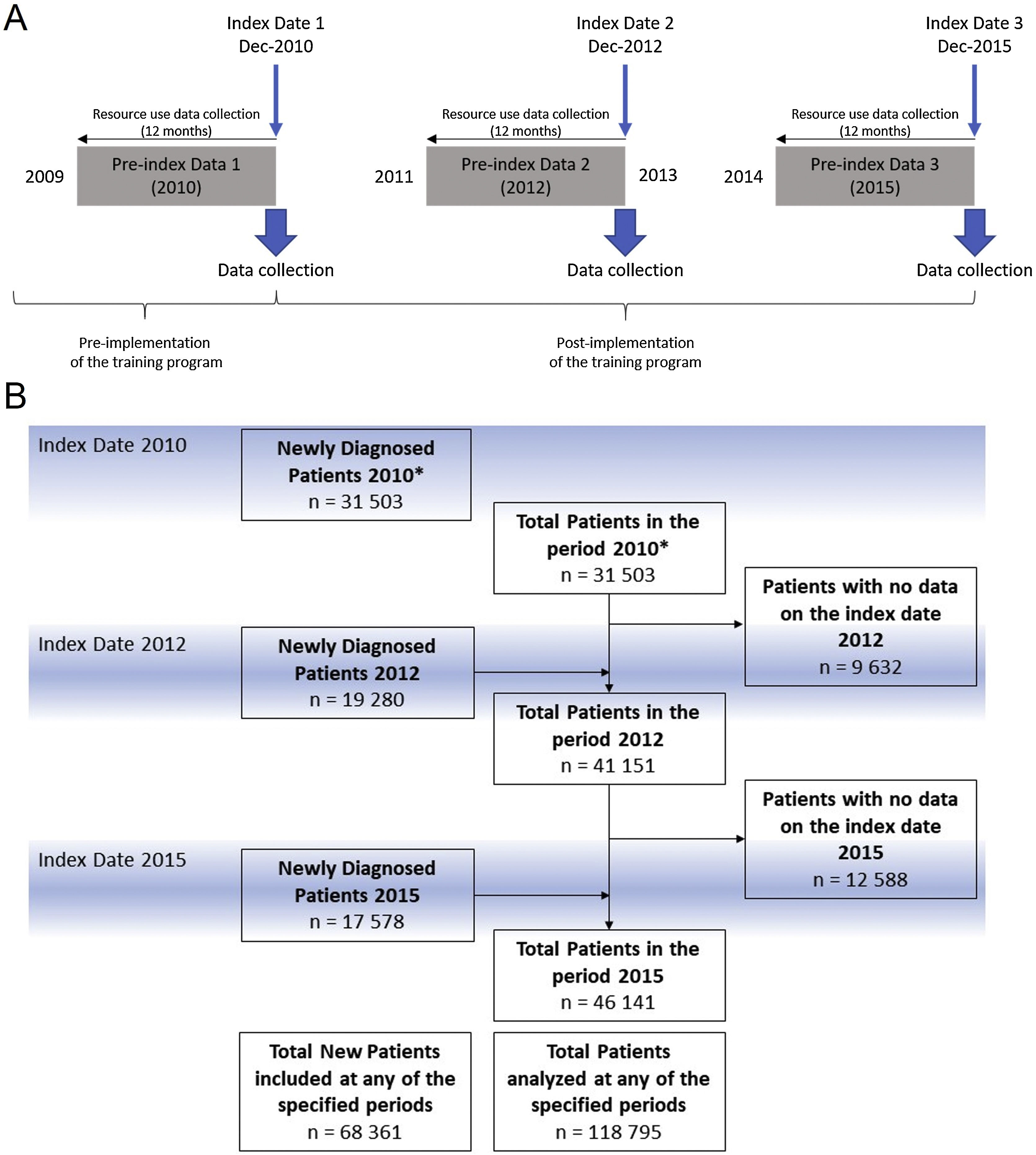

The TP entitled “Training and Research Program in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in the Valencian Community” consisted of lectures delivered by physicians trained in the 2010 consensus on BPH referral criteria12 implemented in a total of 82 PC centers in the Valencian Healthcare System (VHS) in three phases: the first and second included 32 healthcare centers each and were performed during 2011 and 2012, respectively. The third and last included 18 healthcare centers during 2013 and 2014. Evaluation periods were as follows: 1) before the implementation of the training (Jan-Dec 2010); 2) one year after initiation of the program (Jan-Dec 2012) when half of the centers had completed the training; 3) (Jan-Dec 2015) when all the centers had completed the training (Fig. 1A).

PatientsPatients included had to be ≥50 years, attending a VHS center between 2010 and 2015, with a BPH diagnosis confirmed according to the corresponding International Classification of Diseases (9th edition) (ICD-9-CM) codes. Patients with an additional diagnosis of prostate cancer or included in other clinical trials were excluded.

Objectives and variablesThe primary objective was to evaluate changes in BPH management of patients after implementation of the TP. For this purpose, the evolution of quality indicators for diagnosis (International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS] assessment and PSA performed at diagnosis), for treatment (number of patients receiving α-blocker + 5-ARI combination therapy or α-blocker in monotherapy in BPH patients with moderate-severe symptoms), and for treatment outcomes (number of emergency urinary catheterization procedures; number of referrals to urology units; rate of BPH-related surgeries [according to ICD-9-CM codes]; number of IPSS assessments and PSA tests at follow-up) were investigated.

The following secondary variables were also collected to further assess the use of resources related to BPH management: all BPH-related treatments by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification13 (α-adrenoreceptor antagonists, testosterone-5-α-reductase inhibitors, other drugs used in BPH, drugs for urinary frequency and incontinence, and drugs used in erectile dysfunction), and diagnostic tests (general clinical laboratory tests, creatinine, urine sediment, urine dipstick, abdominal ultrasound, and uroflowmetry).

Data sourceData from the patients included in this study, containing ICD-9-CM coded medical conditions, clinical variables, PC visits and referrals to secondary care, laboratory results, and prescribed medication, were retrieved from the outpatient electronic medical record database (ABUCASIS), which is available in all outpatient centers of the VHS and contains anonymized patient records. ABUCASIS is also linked to the Spanish Ministry of Health Minimum Basic Data Set (MBDS) database that records hospital discharge information (including diagnosis and procedures).14

Data collectionAll variables from study patients collected between January 2010 and December 2015 were retrieved for study analysis. The data were retrieved as an aggregate collection of variables from patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria at the moment of the collection at three index dates: December 2010, December 2012, and December 2015. Secondary variables were collected from the 12-month period before each index date (Fig. 1A).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS statistical package version 23 and R (R Code Team, 2020). Categorical variables were described as the frequency and percentage of the variable for the available data, specified for each. Bivariate analysis was performed comparing variables using the Chi-square test. The statistical significance threshold was set at an alpha value of 0.05.

ResultsStudy populationThe study included a total of 68,361 newly diagnosed patients in all periods (all patients with a diagnosis of BPH before 2010 were deemed newly diagnosed at index date 2010). A total of 118,795 patients presented data in all study periods. Fig. 1B shows the disposition of patients included at each index date and the total number of patients analyzed per period.

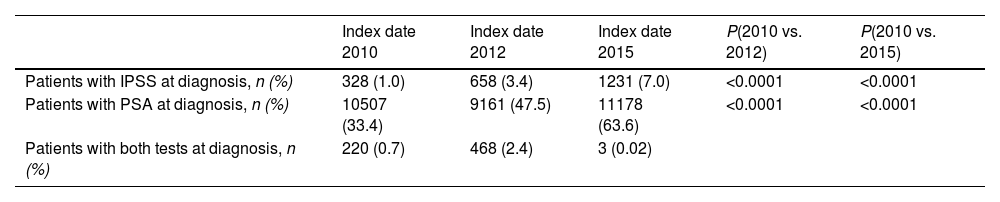

Evaluation of changes in BPH management using diagnostic indicatorsTo evaluate the changes in BPH management after the implementation of the TP, we assessed the evolution of the number of IPSS assessments and PSA tests at diagnosis as quality indicators for diagnosis.

The proportion of patients with IPSS assessment at the time of diagnosis increased three-fold and seven-fold from the first period to the second and third periods, respectively (Table 1). Differences in the number of patients with IPSS assessments at the time of diagnosis were statistically significant between the time periods: 2010 vs. 2012, and 2010 vs. 2015. Similarly, the proportion of patients with a PSA determination at diagnosis increased significantly from the first period to the second and almost doubled from the first period to the third. The differences in the number of patients with a PSA determination at the time of diagnosis were statistically significant between the time periods: 2010 vs. 2012, and 2010 vs. 2015 (Table 1).

Number of patients with the selected tests and questionnaires in each period.

| Index date 2010 | Index date 2012 | Index date 2015 | P(2010 vs. 2012) | P(2010 vs. 2015) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with IPSS at diagnosis, n (%) | 328 (1.0) | 658 (3.4) | 1231 (7.0) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Patients with PSA at diagnosis, n (%) | 10507 (33.4) | 9161 (47.5) | 11178 (63.6) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Patients with both tests at diagnosis, n (%) | 220 (0.7) | 468 (2.4) | 3 (0.02) |

*P corresponding to the comparison between the 2010 and 2012 results; **P corresponding to the comparison between the 2010 and 2015 results.

IPSS: International Prostate Symptom Score; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

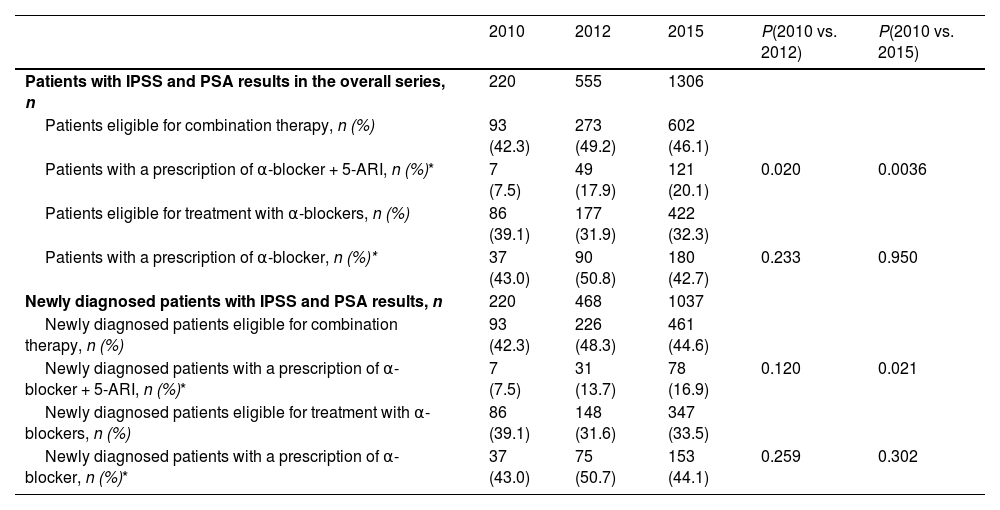

The evolution of prescriptions of the combination therapy (i.e., α-blocker + 5-ARI) or an α-blocker in monotherapy was assessed as an indirect measure to evaluate changes in the management of BPH patients after implementation of the TP (Table 2).

Description of treatments prescribed over the three periods in the overall series and in newly diagnosed patients.

| 2010 | 2012 | 2015 | P(2010 vs. 2012) | P(2010 vs. 2015) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with IPSS and PSA results in the overall series, n | 220 | 555 | 1306 | ||

| Patients eligible for combination therapy, n (%) | 93 (42.3) | 273 (49.2) | 602 (46.1) | ||

| Patients with a prescription of α-blocker + 5-ARI, n (%)* | 7 (7.5) | 49 (17.9) | 121 (20.1) | 0.020 | 0.0036 |

| Patients eligible for treatment with α-blockers, n (%) | 86 (39.1) | 177 (31.9) | 422 (32.3) | ||

| Patients with a prescription of α-blocker, n (%)* | 37 (43.0) | 90 (50.8) | 180 (42.7) | 0.233 | 0.950 |

| Newly diagnosed patients with IPSS and PSA results, n | 220 | 468 | 1037 | ||

| Newly diagnosed patients eligible for combination therapy, n (%) | 93 (42.3) | 226 (48.3) | 461 (44.6) | ||

| Newly diagnosed patients with a prescription of α-blocker + 5-ARI, n (%)* | 7 (7.5) | 31 (13.7) | 78 (16.9) | 0.120 | 0.021 |

| Newly diagnosed patients eligible for treatment with α-blockers, n (%) | 86 (39.1) | 148 (31.6) | 347 (33.5) | ||

| Newly diagnosed patients with a prescription of α-blocker, n (%)* | 37 (43.0) | 75 (50.7) | 153 (44.1) | 0.259 | 0.302 |

IPSS: International Prostate Symptom Score; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

*Percentages are based on the total number of patients eligible for the corresponding treatment.

Throughout the study, in the overall sample, the proportion of patients considered eligible for combination therapy (i.e., IPSS score moderate-severe and PSA > 1.5 ng/mL) increased notably (Table 2). Of the total number of patients eligible for combination therapy, less than one-tenth were receiving it in the first period, while almost one-fifth were receiving it in the second and third periods. The proportion of patients with a prescription for combination therapy increased significantly between the first period and the second and third periods (Table 2). The same significant trend was observed in newly included patients (Table 2).

Conversely, the proportion of patients eligible for α-blocker monotherapy was higher in the first period compared to the second and third periods (Table 2). Nearly half of eligible patients had a prescription for single-agent α-blocker in all periods, and no significant differences in the number of patients receiving this treatment were observed among any of the study periods (Table 2). Similarly, in newly diagnosed patients, no significant differences were observed between the proportion of patients receiving single-agent α-blocker in any of the periods analyzed (Table 2).

Evaluation of changes in BPH management using outcome indicatorsOutcome indicators to evaluate changes in BPH management after the implementation of the TP consisted of the number of catheterizations performed, referrals to the urology unit, BPH-related surgeries, and continued IPSS and PSA follow-up.

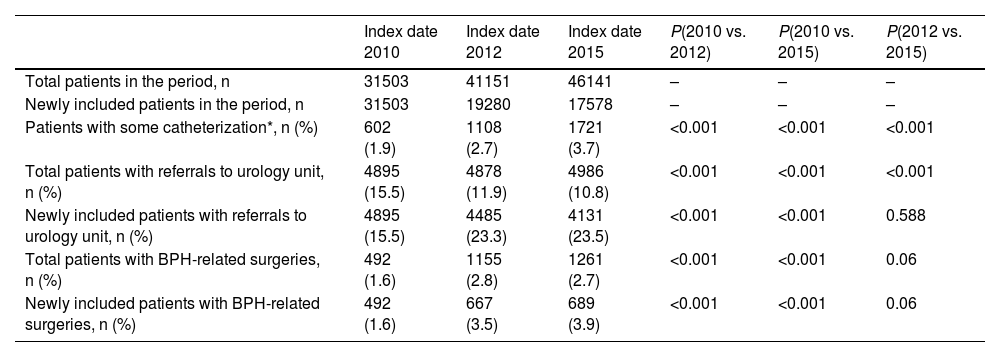

The number of patients in each period in whom any catheterization procedure was performed for acute urinary retention increased significantly over the study duration. However, the rate of procedures performed per patient remained stable: n = 637, n = 1201, and n = 1924 total catheterization procedures were performed in 2010, 2012, and 2015, respectively, at a per-patient rate of 1.1 in all three periods (Table 3). Regarding the number of referrals to urology units, the proportion of patients referred decreased significantly over the study periods (Table 3). Notably, most of the patients referred to the urology unit were newly diagnosed (91.9% and 82.9% of the total referrals were newly diagnosed patients at index dates 2012 and 2015, respectively). Conversely, the proportion of patients that underwent BPH-related surgery increased significantly from index date 2010–2012 and to 2015, but no significant difference was observed in the last period (from index date 2012–2015) (Table 3). More than half of patients undergoing BPH-related surgery were newly diagnosed (57.7% and 54.6% at index dates 2012 and 2015, respectively) (Table 3).

Outcome indicators in the overall series and in newly diagnosed patients.

| Index date 2010 | Index date 2012 | Index date 2015 | P(2010 vs. 2012) | P(2010 vs. 2015) | P(2012 vs. 2015) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients in the period, n | 31503 | 41151 | 46141 | – | – | – |

| Newly included patients in the period, n | 31503 | 19280 | 17578 | – | – | – |

| Patients with some catheterization*, n (%) | 602 (1.9) | 1108 (2.7) | 1721 (3.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total patients with referrals to urology unit, n (%) | 4895 (15.5) | 4878 (11.9) | 4986 (10.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Newly included patients with referrals to urology unit, n (%) | 4895 (15.5) | 4485 (23.3) | 4131 (23.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.588 |

| Total patients with BPH-related surgeries, n (%) | 492 (1.6) | 1155 (2.8) | 1261 (2.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.06 |

| Newly included patients with BPH-related surgeries, n (%) | 492 (1.6) | 667 (3.5) | 689 (3.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.06 |

*Sum of catheterized patients and patients with urinary retention.

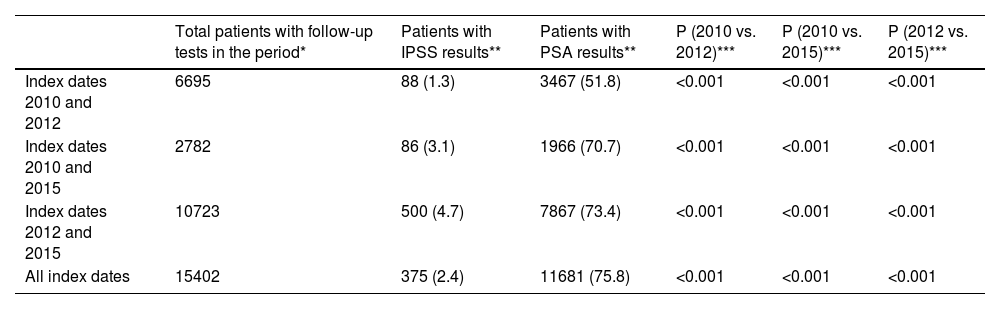

To evaluate the maintenance of IPSS and PSA assessments, only patients with follow-up tests (i.e., patients with at least two consecutive IPSS and PSA assessments) were included. The proportion of patients with recorded IPSS and PSA assessments increased over the study duration with significant differences between all study periods (Table 4).

Evaluation of the continuity of IPSS and PSA assessments during the study.

| Total patients with follow-up tests in the period* | Patients with IPSS results** | Patients with PSA results** | P (2010 vs. 2012)*** | P (2010 vs. 2015)*** | P (2012 vs. 2015)*** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index dates 2010 and 2012 | 6695 | 88 (1.3) | 3467 (51.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Index dates 2010 and 2015 | 2782 | 86 (3.1) | 1966 (70.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Index dates 2012 and 2015 | 10723 | 500 (4.7) | 7867 (73.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| All index dates | 15402 | 375 (2.4) | 11681 (75.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

IPSS: International Prostate Symptom Score; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

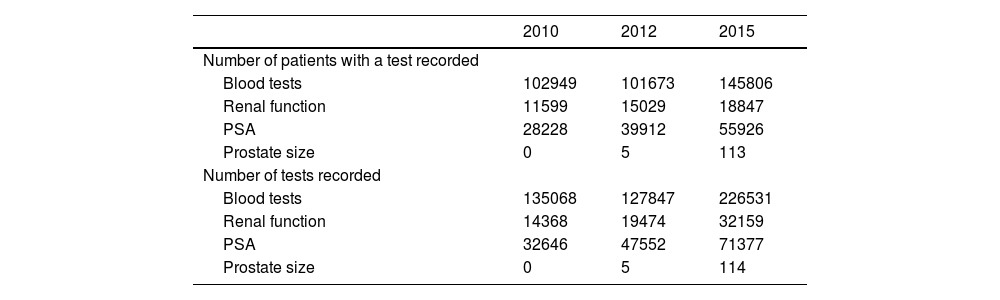

We also examined the use of resources as indicators of the evolution of BPH management, including the number of diagnostic tests performed throughout the study, and the number of patients with a record of these diagnostic tests. Both indicators were higher in the last period compared with the first period of the study (Table 5).

Patients with diagnostic tests for BPH and number of tests performed in each period.

| 2010 | 2012 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with a test recorded | |||

| Blood tests | 102949 | 101673 | 145806 |

| Renal function | 11599 | 15029 | 18847 |

| PSA | 28228 | 39912 | 55926 |

| Prostate size | 0 | 5 | 113 |

| Number of tests recorded | |||

| Blood tests | 135068 | 127847 | 226531 |

| Renal function | 14368 | 19474 | 32159 |

| PSA | 32646 | 47552 | 71377 |

| Prostate size | 0 | 5 | 114 |

PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

In Spain, most BPH patients without complications can be managed by GPs, and a standard BPH management procedure for specialist referral may be of use to health professionals who see these patients.2,15 Thus, we aimed to evaluate changes in real-life BPH management after implementation of the “Training and Research Program in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia of the Valencian Community.”

We observed significant improvements in quality indicators for diagnosis (i.e., IPSS scores and PSA determinations) in all study periods. Likewise, other investigations report the association between the increase in the use of validated tools such as IPSS, as referred in clinical guidelines, with the improvement in the precision of diagnosing patients with BPH in PC settings.16

For men experiencing moderate or severe LUTS at risk of disease progression, clinical guidelines recommend initiating combination treatment.8–10 In the overall study sample we observed a significant increase in the number of patients receiving the combination therapy from the first to the third period. However, the proportion of patients eligible for this therapy according to progression criteria established in clinical guidelines remained much higher.2,12,17,18 In contrast, the proportion of patients with a prescription for an α-blocker therapy remained stable throughout the study and was higher than among those receiving combination therapy. Despite the fact that changes in treatment prescription trends throughout the study indicated a better management of those patients (combination therapy prescriptions increased), patients eligible for combination therapy who actually received it remained low, according to guideline recommendations for patients at risk of disease progression.2,12,17,18 Real-world evidence from Spain's primary care and urology clinics suggests suboptimal treatment practices, as patients meeting progression criteria are not receiving 5-ARI in monotherapy or combination.16 Recent analyses emphasize the importance of promptly initiating combination therapy, showing lower risks of acute urinary retention and BPH-related surgery compared to delayed initiation.19,20 This underscores the critical need to adhere to clinical guidelines across various settings, including PC and urology clinics.

On the other hand, we observed an increase in the number of catheterizations throughout the study but the number of procedures per patient remained stable, resulting in an increase in the total number of patients undergoing catheterization between the first and third study periods.

In the overall study sample, there was a notable decrease in the number of patients referred throughout the study, but a significant increase in referrals for newly diagnosed patients in each period, may be due to the inclusion of patients referred for ultrasounds. Thus, controlled patients were better managed in PC, while newly diagnosed, probably suspicious patients were referred for a better diagnosis. These findings suggest improved management of BPH patients, as the total number of referrals for the entire patient series decreased. Even though these results did not reflect any improvement in the management of BPH patients as a result of the TP, a longer follow-up might be necessary to show the potential impact of training on certain indicators.

We also observed a positive trend in post-therapy management, with a significant increase in patients who underwent follow-up tests (i.e., two or more records in at least two consecutive periods at least), in all study periods. Specifically, the last periods (2012–2015) retrieved a higher proportion of patients with at least two IPSS records, even though the total number of patients accounting for this increase was still suboptimal (<5%). Similarly, we observed an increase in the number of follow-up PSA determinations in all study periods. These results indicate that the IPSS questionnaire and PSA determinations are being increasingly used in follow-up visits.

The main strength of this study is its substantial sample size that met study size predeterminations, reflecting the real-life practice of BPH patients followed in the VHS and ensuring the applicability of the results. This applicability is reinforced by the significant results that confirm the positive impact of the TP on the management of BPH patients in PC. However, limitations apply, primarily the retrospective nature of the study that restricted data collection to information already included in the patient’s clinical record. Additionally, despite the inclusion of many variables, the aggregated data collection approach prevented the analysis of other covariables with known influence on the management of BPH patients, along with individual assumptions and prescription follow-up. Additionally, only IPSS and PSA determinations were considered when assessing the risk of disease progression, due to the impossibility of obtaining quality data on prostate volumes. Finally, all patients included at the first index date (2010) were considered as new patients which could prevent the interpretation of some results. Other studies may contribute to the knowledge in this regard.

Overall, the study results showed a positive impact of the TP on improving the management of BPH patients by GPs in Valencia. The results showed an increasing use of tests, such as IPSS and PSA, in diagnosis and follow-up. Moreover, better therapeutic management according to prescribing guidelines and the decreasing trend of referrals in the overall sample indicated a general improvement in the management of the BPH patient by GPs.

FundingThis work was funded/sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

Conflicts of interestLV, JJ, and AM are employees of GSK and hold shares. The remaining of the authors have nothing to declare.

Author contributionsJN-P, ELA, JCP, and FBM contributed to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition of the data, the interpretation of study data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be submitted for publication.

Medical writing support was provided by Amanda López and Beatriz Albuixech-Crespo of (Medical Statistics Consulting, Valencia, Spain) and funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). Authors would like to acknowledge GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) employees - Alfonso Agra and Natalia Fernandez for their support to carry out this Project.

Please cite this article as: Navarro-Pérez J, López Alcina E, Calabuig Pérez J, Brotons Muntó F, Martínez A, Vallejo L, et al., Nuevas pautas de actuación en la hiperplasia benigna de próstata en la Comunidad Valenciana: un estudio de vida real, Actas Urol Esp. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acuro.2023.11.006