To understand the residents’ perceptions of the, COVID-19 driven, newly implemented online learning systems adopted among accredited urology residency programs nationwide, and their sustainability following the pandemic era.

Materials and methodsA survey was designed and dispersed to urology program coordinators and directors to distribute to their residents.

In the survey, Online education models was the all-encompassing term to describe any form of resident education that occurred online. Anonymous surveys were exported from Survey Monkey and data was analyzed for statistical significance.

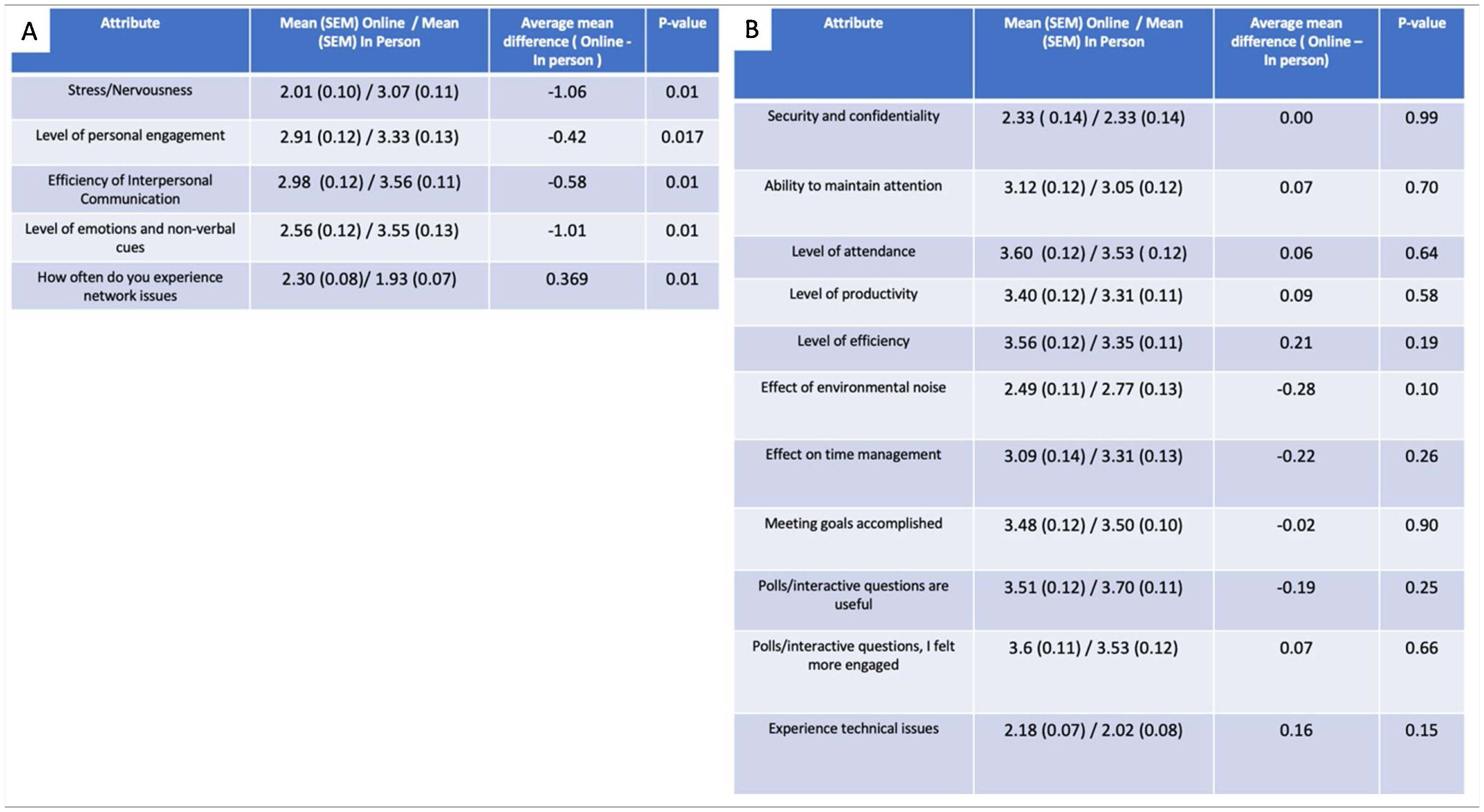

ResultsOver 70% of urology residents agreed or were neutral to the statement that Online education models were equivalent to in-person learning. Only 13% of residents stated that online learning should not be continued following the pandemic. Several different parameters were assessed, and only 5 of them showed statistical significance. Stress, personal engagement, interpersonal communication efficiency and non-verbal cues were all lower with online education models. The only attribute that was scored higher by residents was network connectivity issues.

ConclusionsAn overwhelming majority of urology residents in the United States believe Online education models should continue to be adopted once the pandemic is over.

Comprender la percepción de los residentes respecto a los sistemas de aprendizaje en línea, los cuales, impulsados por la pandemia del COVID-19, han sido recientemente implementados a nivel nacional en los programas de residencia urológica acreditados. Adicionalmente, nos proponemos analizar su sostenibilidad tras la era de la pandemia.

Material y métodosSe diseñó una encuesta para, a través de los coordinadores y directores de programas de urología, difundir a los residentes de urología.

En la encuesta, los modelos de educación en línea englobaron cualquier forma de educación recibida por los residentes que se diera en línea. Las encuestas anónimas se exportaron de Survey Monkey y se analizaron los datos para determinar la significación estadística.

ResultadosMás del 70% de los residentes de urología estuvieron de acuerdo, o mostraron una actitud neutral, ante la afirmación de que los modelos de educación en línea eran equivalentes al aprendizaje presencial. Sólo el 13% de los residentes afirmó que el aprendizaje en línea no debería continuar tras la pandemia. Se evaluaron diversos parámetros, y sólo 5 de ellos mostraron significación estadística. El estrés, el compromiso personal, la eficacia de la comunicación interpersonal y las señales no verbales fueron más bajos para los modelos de educación en línea. El único aspecto al que los residentes dieron mayor puntuación fue el de los problemas de conectividad a una red.

ConclusionesLa gran mayoría de los residentes de urología en Estados Unidos cree que los modelos de educación en línea deben mantenerse una vez terminada la pandemia.

COVID-19 has brought disruption to in-person education at all levels of medical training. With modern technology, there have been many attempts to create ‘tele’-education opportunities for urology residents. As early as 1998, the internet was being used to create educational opportunities1. Furthermore, there have been multiple studies in the literature that have looked at internet-education for urology residents2,3.

In a 2005 study, Cook et al. had residents participate in a tele-teaching seminar on pediatric urology. They found that the residents had a high acceptance rate of tele-teaching and believed that the experience significantly improved their urology foundation2. Salem et al, surveyed 228 residents from Germany and Canada who were asked about their use of new media (internet-based) for education. 45% of their overall education time was spent on new media, with a median of 270 min online3. In Portugal, residents were queried on their use of videos in surgical education, where 98.6% of them used videos to prepare for surgery4. Residents placed a high value on the presence of video didactic illustrations and the presence of narration4.

Pugh et al. notes both the benefits and challenges of incorporating the internet into surgical education. The authors cite work-hour caps and the advance of laparoscopy as two forces that were key in bringing about a paradigm shift in surgical education. They emphasized the use of web-based curricula as a supplement to enhance teaching and learning — not as a substitute5. In this study, we attempt to evaluate the scope of the online education models impact that COVID-19 has had on urology residents across the nation and understand the feasibility of online education models through the use of an online survey.

For the purposes of our study, we defined online education models as follows: Variety of electronic information and telecommunication technologies employed to support long-distance health-related education between health professional-to-health professionals. It includes but is not limited to online courses, online training, online classes, and online video-conferences.

Materials and methodsThe survey was approved by the Academic Medical Center Institutional Review Board. We included an informed consent that emphasized the anonymity of the survey study and subjects. This study obeyed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guideline6–8. Response options included yes or no, Likert Scales, multiple-choice selections.

The survey was designed to ask important questions of the resident’s perception of, access to, and desire to continue learning using an online model. Multiple meetings with current and past urology residents were used to identify areas of concern regarding online education. The questions were designed by ZC and NK and then reviewed by RAG, TP, AA and the IRB prior to survey administration.

We conducted a cross-sectional national survey of American urology residents. We examined their experience regarding online education models during the COVID-19 pandemic. The complete survey is depicted in supplementary material (supplementary file). The survey design was in accordance with the Checklist for Reporting Results of internet E-Surveys9. This was the first and most comprehensive survey regarding this topic to our knowledge.

Participants, recruitment and statistical analysisOur team designed and administered the anonymous survey on the web-based application SurveyMonkey in order to assess the urology residents’ exposure and perspectives to distant learning during COVID-19. Since we are unable to directly email urology residents, we relied on Program Directors, Program Coordinators, and Regional Urologic societies to aid in the distribution of the survey. Urology residency programs emails were available through the AUA website. The survey administrations in the U.S were fully compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, HIPPA, web-based data collection platform. Participants were given 3 weeks from the date of initial mailing until survey closure, and received 3 reminders. We analyzed the Data using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA) version 24.0 IBM Statistics with two-sided p values and α fixed at 0.05. For descriptive statistics, data were reported using percentages and categorical variables and means with standard deviations for continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test, and p values of <0.05 were considered significant.

ResultsResident demographicsUrology residents across the country were surveyed about virtual resident education. Surveys were distributed to Program Directors, Program Coordinators, and regional urologic societies willing to aid in the distribution of the survey to their resident; therefore we were unable to gauge an appropriate response rate of the survey. There was a response from 103 residents; among them, forty-nine percent were between the age of 25 and 30. Thirty-one to thirty-five was the next highest representation at 31%, followed by those over 36-years-old (19. 5%) and those under or equal to 24 (1.09%) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Seventy-three percent of responders were male, which is in line with the current distribution of urology residents10. Fifty-nine percent of responders were married, and another 16% were cohabitating. Twenty-four percent were single. Fifty-seven percent of residents had 0 dependents, followed by 21% having 1, 13% with 2, 9% with 3, and 1% with 4 (Supplementary Fig. 1B–D). These commonly asked demographic questions were asked to better understand if residents with other people in the household impacted their views of online education compared to their single counterparts. Lastly, 42% of responses came from the Southeastern Section, then the Mid-Atlantic (12.9%). The Western, South Central, North Central, and North Eastern each made up 8.6% of residents, New England was 7.5%, and lastly, New York with 3% (Supplementary Fig. 1E).

Past and current online education modelsResidents were asked if online education models existed prior to COVID-19 and 26.4% confirmed virtual learning existed, however due to the nature of the survey, we are unable to determine which virtual learning model was in place (Fig. 1A). When considering what percentage of their current educational models within their respective urology residency programs should use an online education models platform, 37% replied: 0–20%, followed by 35% chose 21–40%, 17% chose 41–60%, 8% chose 61–80 %, and 2% elected for 81–100% (Fig. 1B). In an attempt to gauge how often residents were using online education models per week, 2−3 h was the most common, then 3−4 h, 6+ h, 4−5 h, and lastly 1−2 h and 5−6 h tied at the bottom (Fig. 1C). One resident had no current online education models.

Resident education learning opportunities. A. Poll of online education models prior to COVID-19. B. Residents feelings about what percentage of their education should be virtual. C. Hours of a week dedicated to online learning. D and E. Educational events that are used or should be conducted online. F. Device used to attend a virtual learning event. G. Platforms used to attend event.

As of June 25th, 2020, when the survey was closed, 85% of programs had transitioned Morbidity and Mortality conferences to an online/virtual platform. 82% of programs elected for Grand Rounds to be presented via online education models. 80% of didactics sessions, 73% of journal clubs, 67% of lectures, and 13% of programs offered OR simulation via online education models (Fig. 1D). Urology residents agreed that all educational activities could be transitioned to an online format, except for Grand Rounds where only 35% of residents believed that this activity should be presented online (Fig. 1E).

Electronic devices used to attend and participate in online education models were analyzed. 90% of residents used a laptop. Half also stated they have used their phone to attend. Tablets and third-party computers were among the least used (Fig. 1G). As far as platforms used, Zoom was the most common (90%), followed by WebEx (52%), Skype (13%), Google (10%), and other programs (9%), and institutional specific programs (7%) (Fig. 1F).

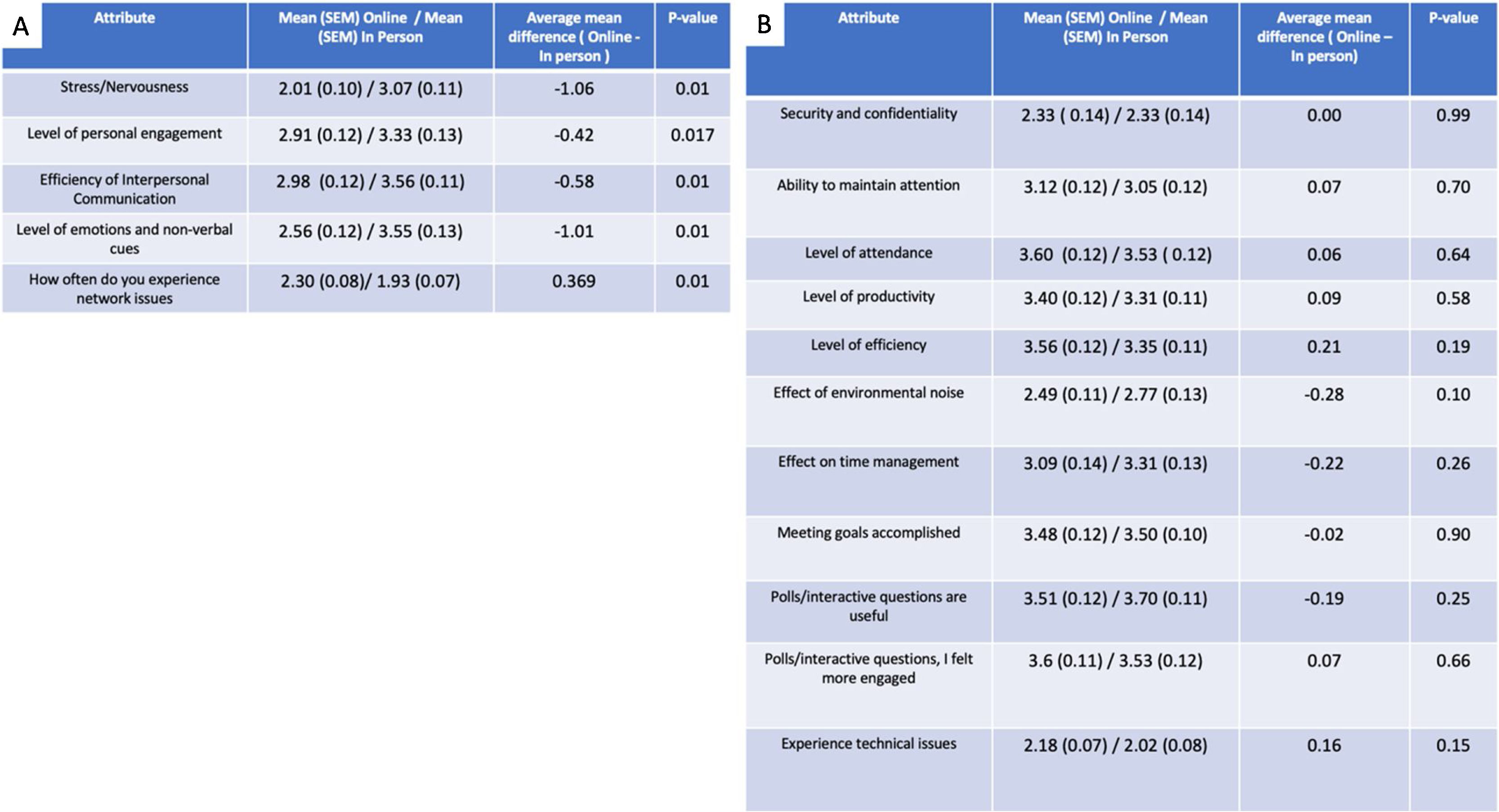

In-Person vs online education models personal attributesSeveral attributes were ranked on a Likert scale to compare how a resident felt about In-Person Education and online education models. A score of 1 = very low and a score of 5 = very high. Stress and Nervousness had a whole point lower mean difference (Telehealth – In person, −1.06) associated with online education models (p < 0.01) (Table 1). When stratified by the number of dependents in the household, those with less than 3 members felt that their stress/nervousness was decreased when utilizing online education compared to in-person education (Supplemental Fig. 2). The level of personal engagements mean difference was −0.42 when online education models was employed (p = 0.017) (Table 1). Efficiency of interpersonal communication had a mean difference of −0.59 and level of emotions and non-verbal cues conveyed, mean difference −1.01 were both significantly lower (p < 0.01 and p < 0.01). Internet connectivity, including lack of internet, intermittent internet, dropped connection was another concern that was statistically significant between the two groups (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2A). All other non-significant attributes tested are listed in Fig. 2B.

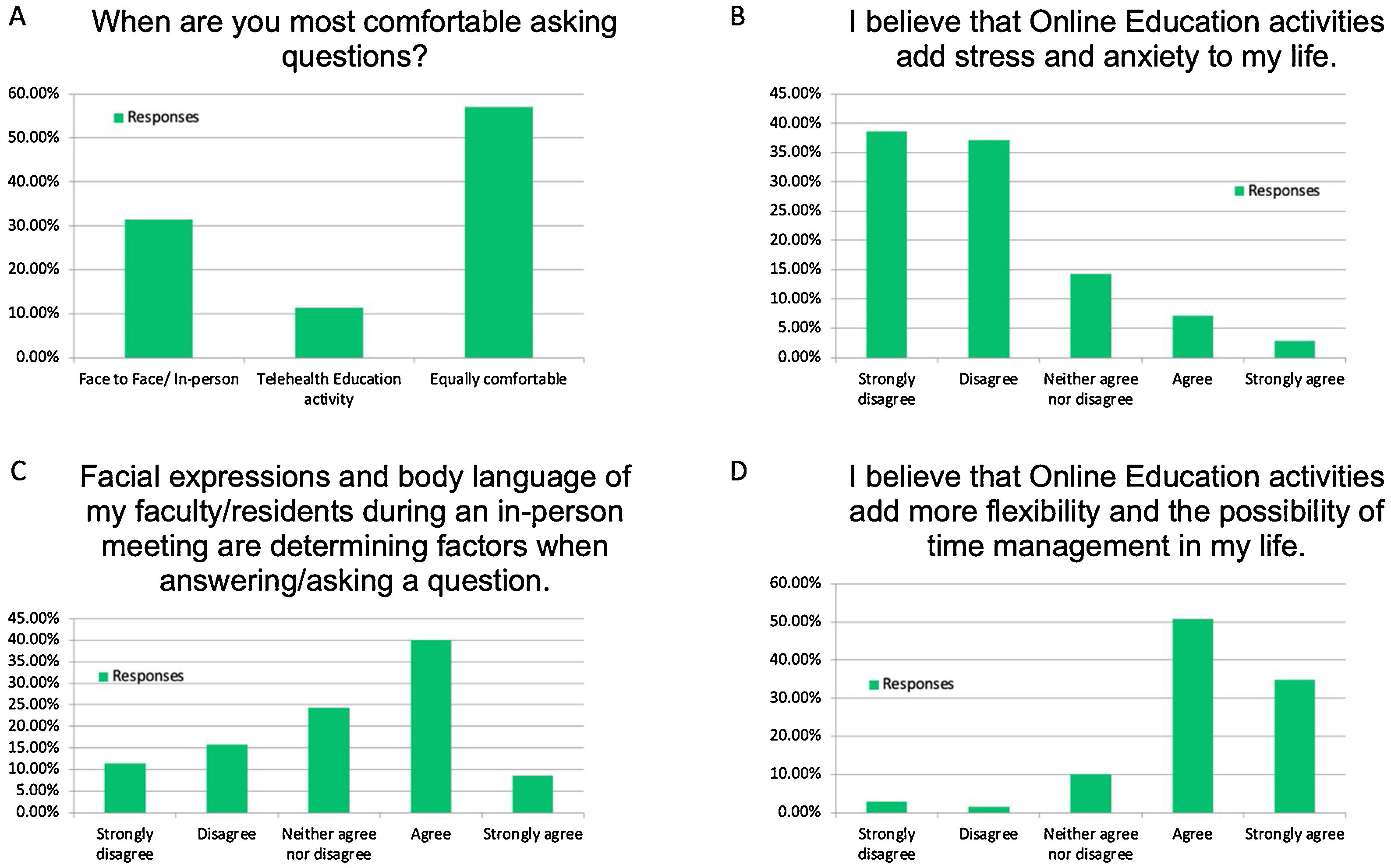

Engagement of residents with online education models and in-person meetings. A. Location of where residents feel most comfortable asking questions. B. Stress and anxiety with online education models. C. Facial expression influence on question asking. D. How residents feel Online education models influences time flexibility.

57% of residents indicated that they were equally comfortable asking questions in-person or virtually. 31% preferred in-person, while the remaining 12% would preference online (Fig. 2A). 76% strongly disagree or disagree that online education models add stress and anxiety to their life, 14% are neutral, and 10% feel that it does (Fig. 2B). 49% of residents said that facial expressions and body language are a determining factor when answering a question at an in-person event, while 24% were neutral and 27% said it did not affect them (Fig. 2C). 85% of participants said that online education models can add flexibility and time management to their life. 10% were neutral, and the remaining 6% felt online education models decreased their flexibility (Fig. 2D).

Online education models encourage education and collaborationUsing a Likert scale where 1 = never and 5 = always, residents were asked about continual education as a result of online education models. Residents were asked if they missed an education session that they would watch/listen to this session at a later time. An average of 3.7 where 3 is sometimes and 4 is usually was reported. Taking recorded lectures one step further, residents indicated that an E-learning library (scored 4.0) would usually be used if available. Lastly, an average of 3.8 was calculated for re-watching recorded online education models (Supplementary Fig. 3A).

Ninety percent of residents believe that online education models can foster new collaborations (Supplementary Fig. 3B). This is further demonstrated by a vast majority of residents attending elective online education models. Since COVID-19 has happened, 87% of residents have stated that they used online education models outside of their required learning, with almost 50% using outside learning more than ten times (Supplementary Fig. 3C).

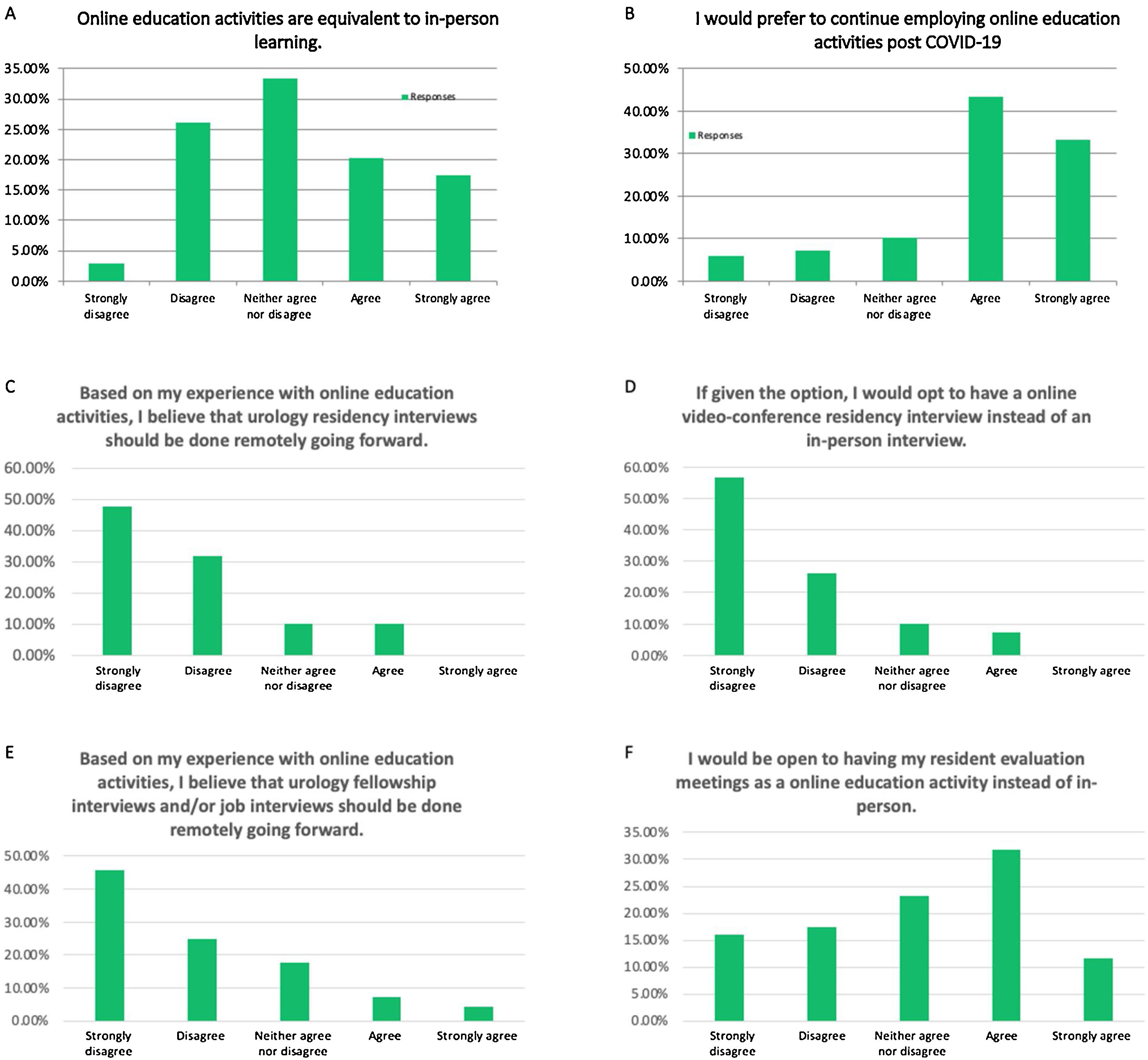

Future applications of online education models for residentsIn attempting to understand if online education models is equivalent to in-person learning, the question was asked directly in the survey. 33% of residents neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement. 20% of residents agreed and 17% strongly agreed that the two were equivalent. 26% of residents disagreed, and 3% strongly that they were equal (Fig. 3A). When polled if online education models should be continued after the pandemic, 77% felt that it should, 10% were neutral, and 13% believe it should stop (Fig. 3B).

Future applications for online education models. Likert Scale response of Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. Percentage of responses are recorded. A. Residents opinion towards the equivalency of Online education models and In-Person education. B. Should Online education models be continued post-COVID-19. C-E reveals resident responses of residency and fellowship interviews should be conducted remotely. F. Residents’ opinions of evaluation meetings being virtual.

Regarding future residency interviews, 79% of residents believed future residency interviews should not be conducted remotely going forward (Fig. 3C). Similarly, 83% of residents would choose an in-person interview over an online one (Fig. 3D). These same feelings were held for fellowship interviews where 70% said the interview should not be conducted virtually (Fig. 3E). Residency feedback with superiors does seems to be an even split between wanting and in-person and virtual assessment (Fig. 3F).

DiscussionSince COVID-19, the conventional instructional and educational models have been dismantled. Reflection of the modified education models should be analyzed to determine if these new adaptations are feasible. Over 100 urology residents provided us insight into their educational adaptations and only 13% would not wish to adopt virtual education in the future. Therefore, we may conclude that online education is a suitable learning modality for residents and should be heavily considered in future educational endeavors.

As reported by the majority of the residents surveyed, online education models provided adequate teaching, and in many instances, a satisfactory alterative for the traditional educational model. In addition to the obvious safety and public health protection it provides, the advantages of distance learning are multiple. This experience provides autonomy and self-learning to the residents, which has been reported in the literature as one of the attractive elements of this methodology11,12. This “Learner autonomy” has been shown to be of valuable asset in the success of distance learning13,14. Furthermore, online education models provides a flexibility that is not afforded with any other education strategy15. The overall average of responses obtained in our study shows residents are willing to use a learning library and would re-watch recorded education activities. Given the high rate of burnout in the urology field, any time-saving modality should be considered16. The flexibility that online education models offer when compared to physical learning is very likely to enhance the productivity and focus of the residents as they will have the option to actually choose topics of their interest as well as follow their own schedule and personal pace17,18. In the United States, within the collaborative COVID-19 lecture series at the University of California San Francisco, over 1000 survey responses demonstrated the effectiveness of lectures and their capacity to educate globally19. Other academic groups held urology-focused education as reviewed by Smigelski et al.20 Additionally, these collaborative models are seen in other specialties21.

This study demonstrates residents’ opinions on the feasibility of online education models. Although the results have strong indications that online education models are favorable, there are some pitfalls in the present study. The sample size is relatively small. It is undetermined how many residents the survey officially reached, due to the technical difficulties during the first weeks of the pandemic. Also, a majority of program coordinators were working from home, and it is unsure if emails were reaching out to their programs. Additionally, we did not have the list of all urology residents individually, therefore it is unknown if the survey was delivered to them. Moreover, the geographic distribution has a major focus on the Southeastern Section of the AUA. All 8 AUA sections are represented in the survey; however, there is no uniform distribution. This is most likely due to recognition of our institutional name in the southeast. Lastly, our survey was sent only to program coordinators and program directors, who were also working under new conditions and limited our capacity to reach each office successfully.

ConclusionThe opportunities provided by online education models are unlimited. They have proven to be an adequate salvage of urology residents’ education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Residents in the survey are overwhelmingly supportive of the feasibility of online education models in the future. Given some of the pitfalls of rapid technology advances, we suggest that the most realistic and applicable model would be a hybrid between the traditional in-person teaching and online education models. Allow those who want in-person learning to come, while simultaneously streaming and recording the education activity for others. The exact combination of these two approaches should be the focus of future discussions between urology education committees, societies, and trainees. Even after the COVID-19 crisis fades away and the dust settles, we believe that online education models will be here to stay.