Some studies have suggested that prenatal paracetamol exposure might associate with the risk of child asthma. However, other studies have not confirmed this result. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to investigate their relationship.

MethodsTwo authors searched Pubmed and Embase databases up to June 2016. The strength of the association was calculated with the OR and respective 95% CIs. The random-effects model was chosen to calculate the pooled OR.

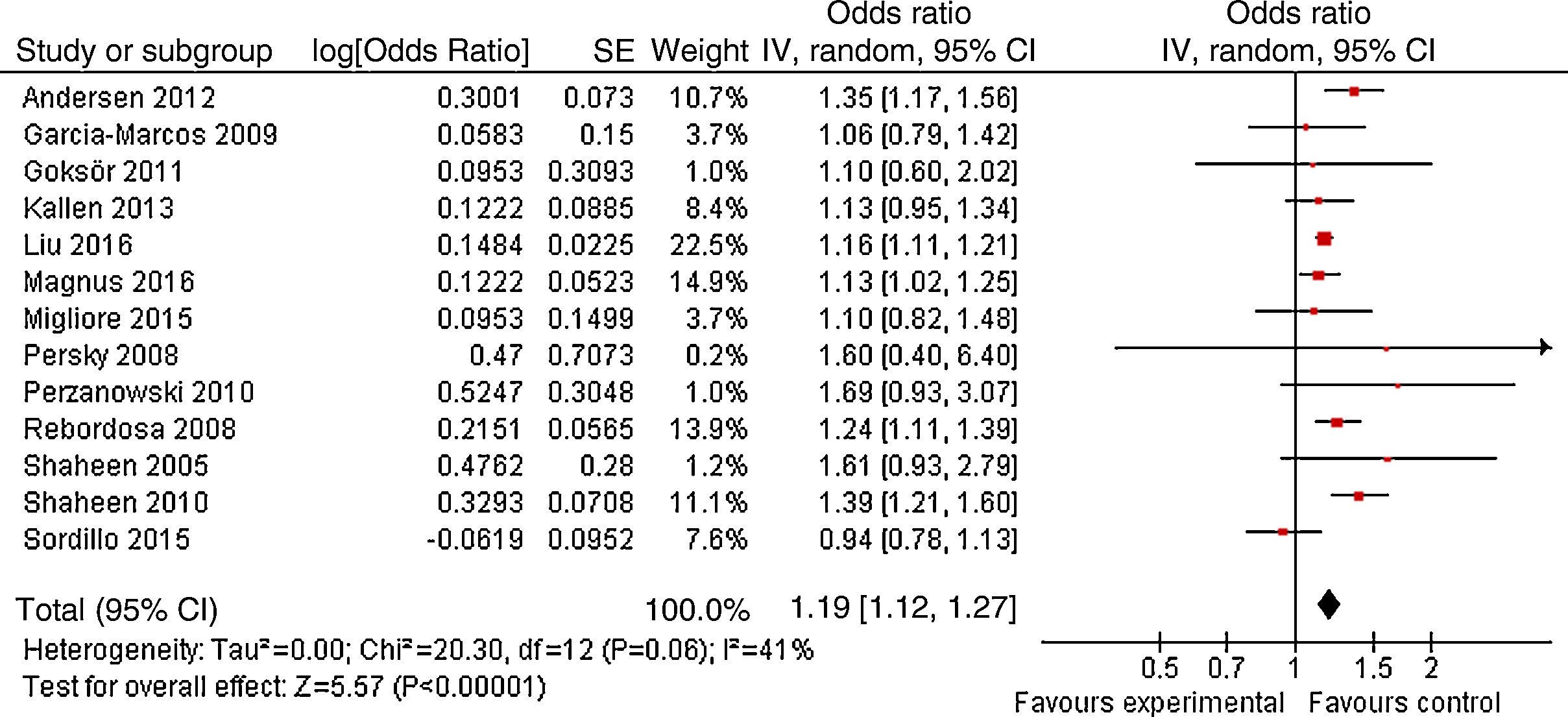

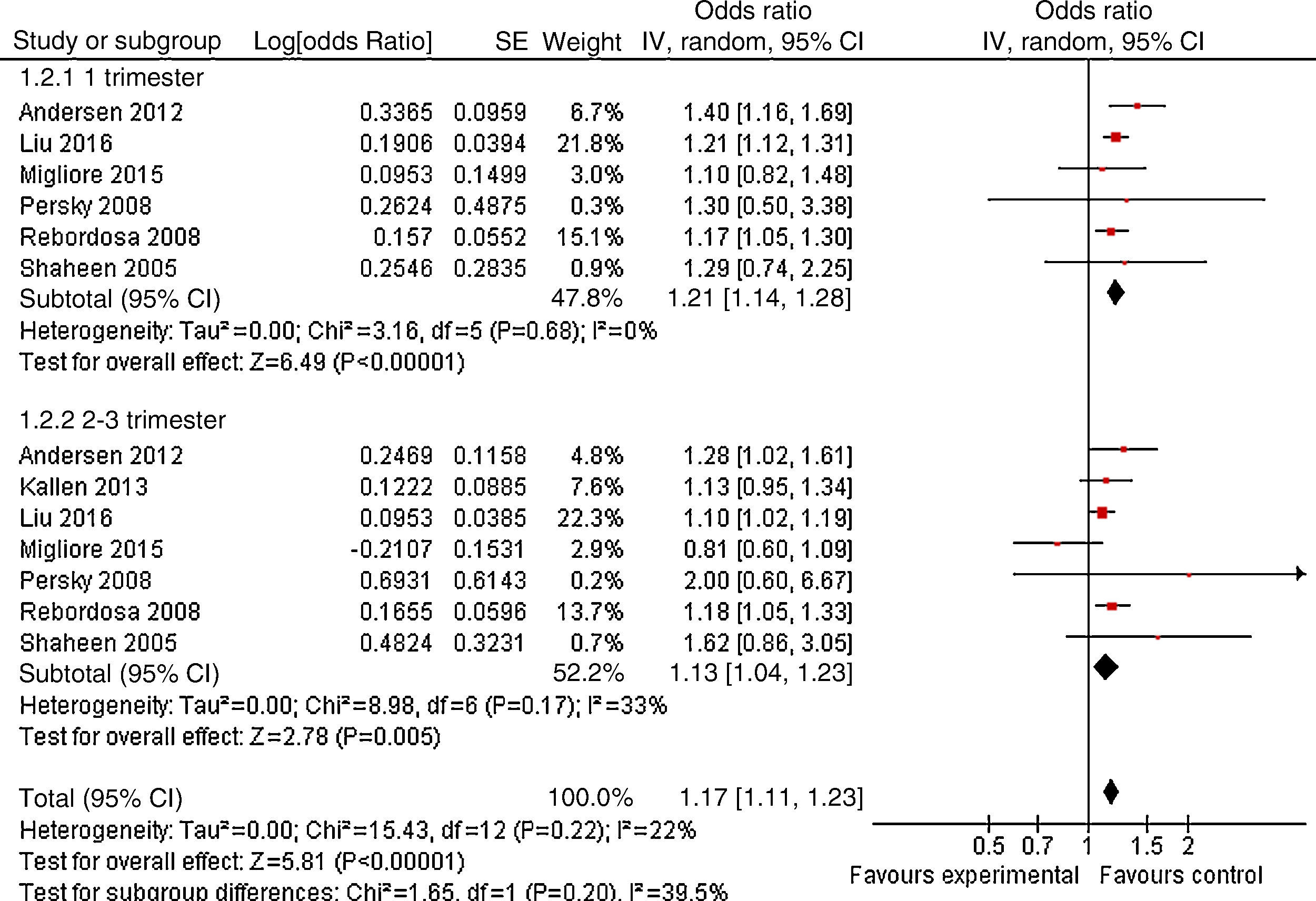

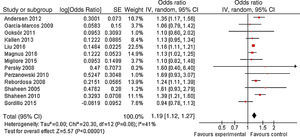

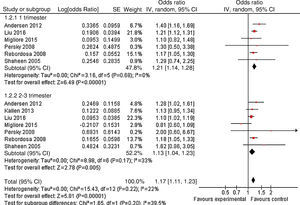

ResultsA total of 13 articles of more than 1,043,109 individuals were included in the meta-analysis. A statistically significant association between prenatal paracetamol exposure and child asthma risk was found. The data showed that prenatal paracetamol exposure could increase the risk of child asthma (OR=1.19; 95% CI, 1.12–1.27; P<0.00001) in a random-effect model. Six studies reported paracetamol exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy. We found that paracetamol exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy was associated with increased risk of child asthma (OR=1.21; 95% CI, 1.14–1.28; P<0.00001). Furthermore, we observed that paracetamol exposure during the 2–3 trimesters of pregnancy was also associated with child asthma risk (OR=1.13; 95% CI, 1.04–1.23; P=0.005).

ConclusionsThis study suggested that prenatal paracetamol exposure was significantly associated with the increased risk of child asthma.

Asthma is a common chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways which is associated with airway hyperresponsiveness, smooth muscle spasm, and airflow obstruction. Over recent years, the global rates of asthma have increased significantly. Asthma affects about 9% of children in the world. Its frequency fluctuates from 1 to 30% among countries, being higher in Western countries.1

Paracetamol is the most commonly used analgesic and antipyretic worldwide and is widely available over the counter (OTC).2 In the United States approximately 50 million adults consume products containing paracetamol every week. Paracetamol is used by distinct populations spanning across life stages, who have varying information-seeking priorities. These include young children, pregnant women, and the elderly. Some studies suggested that prenatal paracetamol exposure might associate with the risk of child asthma. However, other studies did not confirm this result.3–15 Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to investigate their relationship.

MethodsPublication searchTwo authors searched Pubmed and Embase databases up to June 2016. The search criteria “paracetamol” and “asthma” were used in text word searches. The reference lists of the selected articles were also manually examined to find relevant studies that were not discovered during the database searches. There was no language restriction.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaStudies were selected for meta-analysis if they met the inclusion criteria as follows: (1) cohort or case–control study design; (2) studies that investigated the association between prenatal paracetamol exposure and the risk of child asthma. The following exclusion criteria were defined as follows: (A) incomplete raw data, (B) repetitive reports, and (C) material and methods used were not well described or reliable.

Data extractionTwo investigators extracted all variables and outcomes of interest independently. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus. Data on first author and year of publication, study design, race, follow-up duration, sample size, and confounders were extracted.

Quality assessmentThe included studies were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). The NOS employs a star rating system to assess quality from three broad perspectives of the study: (1) selection of the study groups; (2) comparability of the groups; and (3) identification of the exposure (for case–control studies) or outcome of interest (for cohort studies). Scores ranged from 0 to 9 stars. We considered a study awarded 0–3, 4–6, or 7–9 as a low-, moderate-, or high-quality study, respectively.

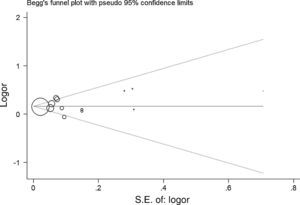

Statistical analysisThe strength of the association between prenatal paracetamol exposure and child asthma risk was calculated with the OR and respective 95% CIs. The significance of the pooled OR was determined by the Z test, and P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was assessed with the I2 statistics. The random-effects model was chosen to calculate the pooled OR. The presence of publication bias was assessed by a visual inspection of a funnel plot. All statistical tests were carried out using the Revman 5.1 software (Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark) and STATA 11.0 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

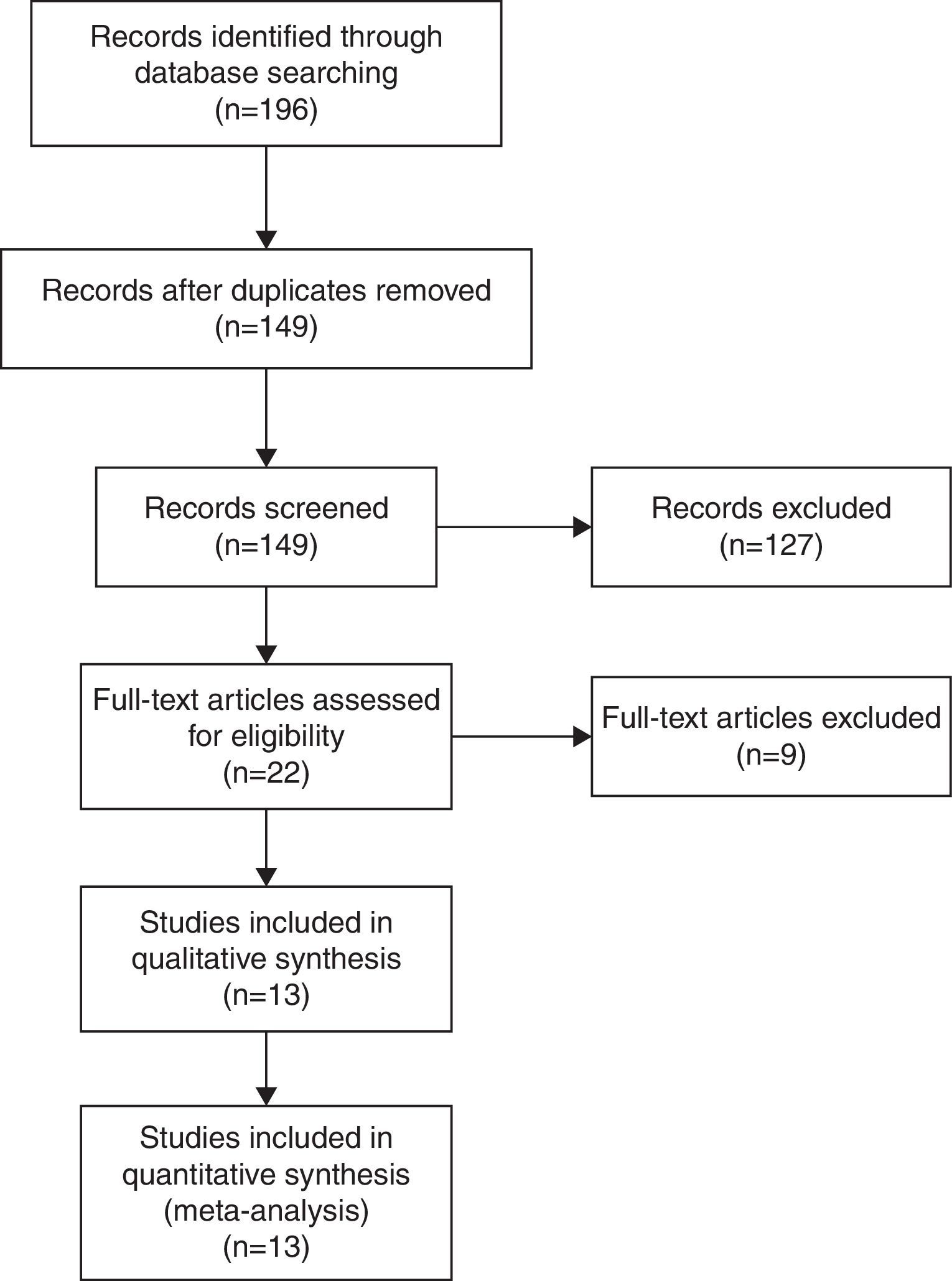

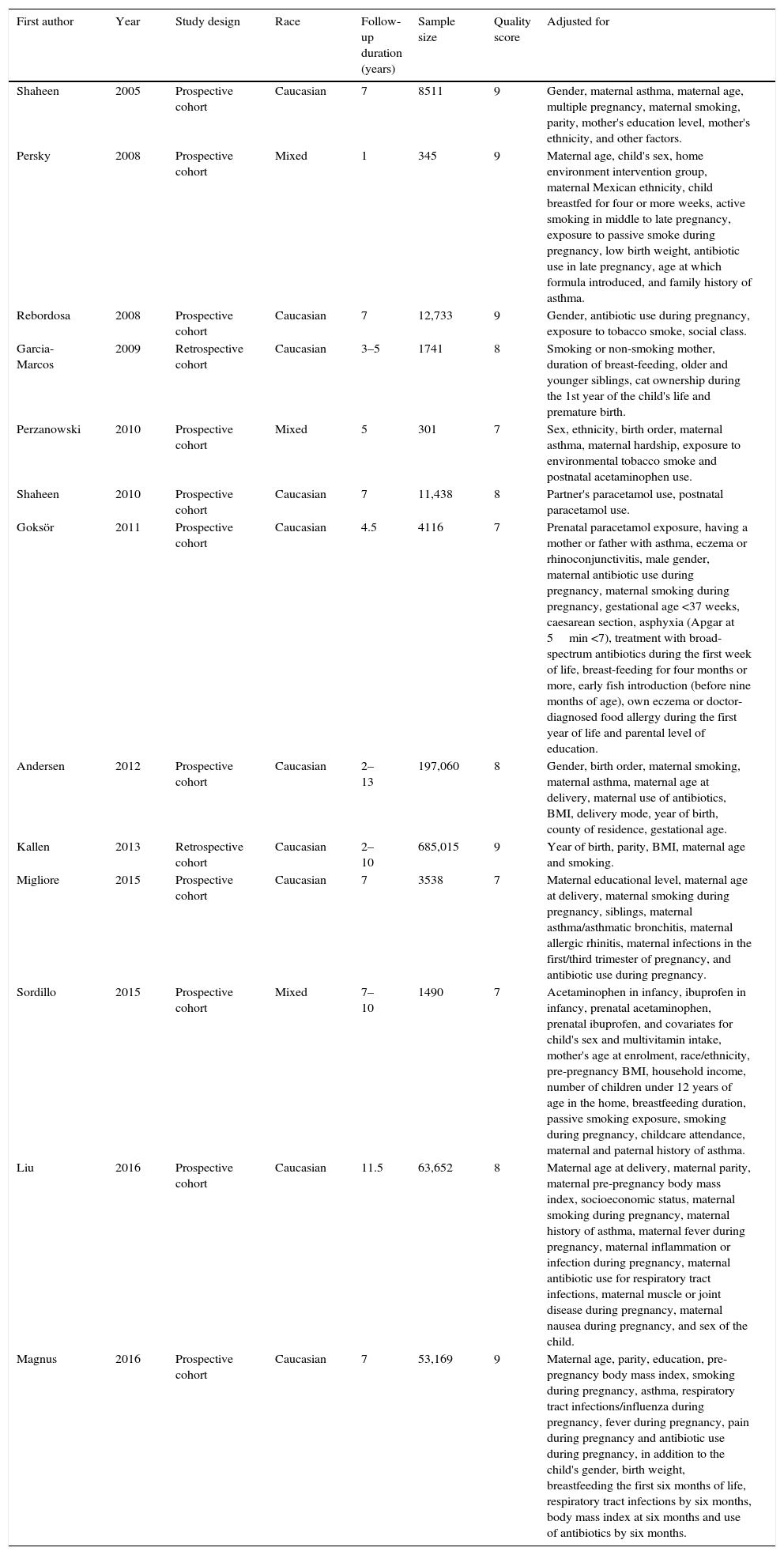

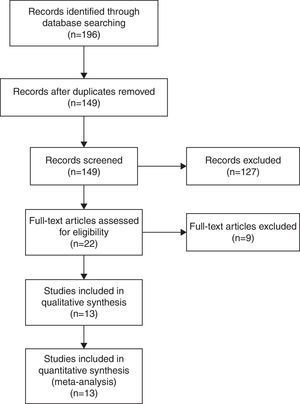

ResultsLiterature searchThe initial literature search retrieved 196 relevant articles. After carefully screening the titles, texts, and abstracts, a total of 13 articles of more than 1,043,109 individuals were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Table 1. All studies included were in accordance with NOS scale and all studies defined as high-quality study.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| First author | Year | Study design | Race | Follow-up duration (years) | Sample size | Quality score | Adjusted for |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaheen | 2005 | Prospective cohort | Caucasian | 7 | 8511 | 9 | Gender, maternal asthma, maternal age, multiple pregnancy, maternal smoking, parity, mother's education level, mother's ethnicity, and other factors. |

| Persky | 2008 | Prospective cohort | Mixed | 1 | 345 | 9 | Maternal age, child's sex, home environment intervention group, maternal Mexican ethnicity, child breastfed for four or more weeks, active smoking in middle to late pregnancy, exposure to passive smoke during pregnancy, low birth weight, antibiotic use in late pregnancy, age at which formula introduced, and family history of asthma. |

| Rebordosa | 2008 | Prospective cohort | Caucasian | 7 | 12,733 | 9 | Gender, antibiotic use during pregnancy, exposure to tobacco smoke, social class. |

| Garcia-Marcos | 2009 | Retrospective cohort | Caucasian | 3–5 | 1741 | 8 | Smoking or non-smoking mother, duration of breast-feeding, older and younger siblings, cat ownership during the 1st year of the child's life and premature birth. |

| Perzanowski | 2010 | Prospective cohort | Mixed | 5 | 301 | 7 | Sex, ethnicity, birth order, maternal asthma, maternal hardship, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and postnatal acetaminophen use. |

| Shaheen | 2010 | Prospective cohort | Caucasian | 7 | 11,438 | 8 | Partner's paracetamol use, postnatal paracetamol use. |

| Goksör | 2011 | Prospective cohort | Caucasian | 4.5 | 4116 | 7 | Prenatal paracetamol exposure, having a mother or father with asthma, eczema or rhinoconjunctivitis, male gender, maternal antibiotic use during pregnancy, maternal smoking during pregnancy, gestational age <37 weeks, caesarean section, asphyxia (Apgar at 5min <7), treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics during the first week of life, breast-feeding for four months or more, early fish introduction (before nine months of age), own eczema or doctor-diagnosed food allergy during the first year of life and parental level of education. |

| Andersen | 2012 | Prospective cohort | Caucasian | 2–13 | 197,060 | 8 | Gender, birth order, maternal smoking, maternal asthma, maternal age at delivery, maternal use of antibiotics, BMI, delivery mode, year of birth, county of residence, gestational age. |

| Kallen | 2013 | Retrospective cohort | Caucasian | 2–10 | 685,015 | 9 | Year of birth, parity, BMI, maternal age and smoking. |

| Migliore | 2015 | Prospective cohort | Caucasian | 7 | 3538 | 7 | Maternal educational level, maternal age at delivery, maternal smoking during pregnancy, siblings, maternal asthma/asthmatic bronchitis, maternal allergic rhinitis, maternal infections in the first/third trimester of pregnancy, and antibiotic use during pregnancy. |

| Sordillo | 2015 | Prospective cohort | Mixed | 7–10 | 1490 | 7 | Acetaminophen in infancy, ibuprofen in infancy, prenatal acetaminophen, prenatal ibuprofen, and covariates for child's sex and multivitamin intake, mother's age at enrolment, race/ethnicity, pre-pregnancy BMI, household income, number of children under 12 years of age in the home, breastfeeding duration, passive smoking exposure, smoking during pregnancy, childcare attendance, maternal and paternal history of asthma. |

| Liu | 2016 | Prospective cohort | Caucasian | 11.5 | 63,652 | 8 | Maternal age at delivery, maternal parity, maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index, socioeconomic status, maternal smoking during pregnancy, maternal history of asthma, maternal fever during pregnancy, maternal inflammation or infection during pregnancy, maternal antibiotic use for respiratory tract infections, maternal muscle or joint disease during pregnancy, maternal nausea during pregnancy, and sex of the child. |

| Magnus | 2016 | Prospective cohort | Caucasian | 7 | 53,169 | 9 | Maternal age, parity, education, pre-pregnancy body mass index, smoking during pregnancy, asthma, respiratory tract infections/influenza during pregnancy, fever during pregnancy, pain during pregnancy and antibiotic use during pregnancy, in addition to the child's gender, birth weight, breastfeeding the first six months of life, respiratory tract infections by six months, body mass index at six months and use of antibiotics by six months. |

BMI, body mass index.

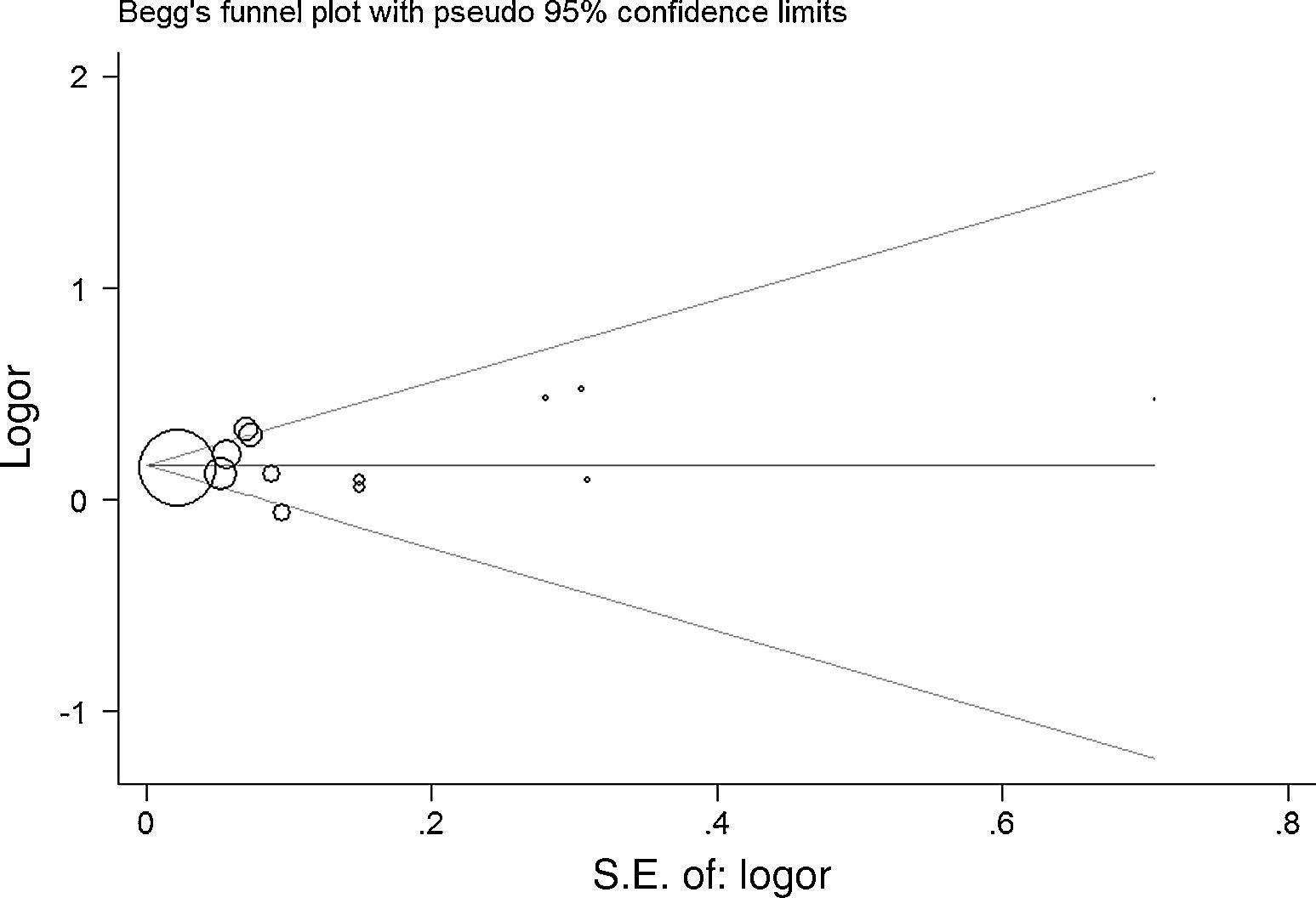

As shown in Fig. 2, a statistically significant association between prenatal paracetamol exposure and child asthma risk was found. The data showed that prenatal paracetamol exposure could increase the risk of child asthma (OR=1.19; 95% CI, 1.12–1.27; P<0.00001) in a random-effect model. Six studies reported paracetamol exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy. We found that paracetamol exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy was associated with increased risk of child asthma (OR=1.21; 95% CI, 1.14–1.28; P<0.00001; Fig. 3). Furthermore, we observed that paracetamol exposure during the 2–3 trimesters of pregnancy was also associated with child asthma risk (OR=1.13; 95% CI, 1.04–1.23; P=0.005; Fig. 3). The funnel plot is symmetrical (Fig. 4), suggesting no publication bias. Egger test further verified that no publication bias existed (P=0.51).

This meta-analysis suggested prenatal paracetamol exposure might increase the risk of child asthma. Paracetamol exposure during the first trimester and 2–3 trimesters could also increase child asthma risk.

Thiele et al. provided strong evidence that prenatal paracetamol interfered with maternal immune and endocrine adaptation to pregnancy, affected placental function, and impairs foetal maturation and immune development.16 Dimova et al. found that acetaminophen decreased intracellular GSH in human pulmonary macrophages and type II pneumocytes and the secretion of TNF-alpha and possibly IL-6 by human pulmonary macrophages.17 Kozer et al. suggested that paracetamol was associated with reduced antioxidant status and erythrocyte glutathione concentrations.18

Several limitations should be identified. First, as a meta-analysis of observational studies, it was prone to bias (e.g., recall and selection bias) inherent in the original studies. However, the adjusted ORs were used in this meta-analysis, suggesting that our results were robust. Second, lacking the original data of the eligible studies limited the evaluation of the subgroup analyses by gender, age, and other factors. Third, almost all the studies were performed in Caucasian populations. Thus, our results may be applicable only to this population.

In conclusion, this study suggested that prenatal paracetamol exposure was significantly associated with the increased risk of child asthma.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestNone.

This study is supported by Student's Platform for Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of Jilin University (Nos. 2015791178 and 2015791168).