Staphylococcus aureus causes numerous mild to severe infections in humans, both in health facilities and in the community. Patients and health care workers (HCWs) may disseminate strains during regular medical examinations or hospitalization. The aim of this study was to determine the nasal carriage rate of methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant S. aureus among health care workers at Hospital Provincial del Centenario, a public general hospital in Rosario, Argentina. A transversal study was conducted on 320 health care workers. Nasal swabs were taken and presumptive S. aureus colonies were isolated. Bacterial identity and methicillin resistance status were confirmed by amplification of the nuc and mec genes. Chi square test and Fisher exact test were used for statistical analysis. Of 320 HCWs, 96 (30%) were nasal carriers of S. aureus, 20 of whom (6.3%) carried methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and 76 (23.7%) methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA). Carriage was within thepublished values for physicians (30%) and higher for technicians (57%). Accompanying resistance (62/96, 64.6%) was detected, including resistance to fluoroquinolones (23/96, 24%), aminoglucosides (13/96, 13.5%) or to macrolides (33/96, 34.4%). All the strains were susceptible to vancomycin whereas only 3.1% (3/96), all of them on MSSA strains, were resistant to mupirocin. This study is the first one of its kind in Argentina and one of the few performed in South America, to highlight the relevance of nasal carriage of MRSA and MSSA in health care personnel and brings to light the need for consensus recommendations for regular S. aureus carriage screening as well as for decolonization strategies.

Staphylococcus aureus es agente causal de numerosas infecciones en humanos, que pueden ser desde leves hasta graves, y circula tanto en la comunidad como en las instalaciones de los centros de salud. Los pacientes y los trabajadores de la salud pueden diseminar cepas durante los exámenes médicos de rutina o durante la hospitalización. El foco de este estudio fue determinar la tasa de portación nasal de S. aureus sensible o resistente a meticilina en trabajadores de la salud del Hospital Provincial del Centenario, un hospital público de atención primaria en Argentina. Se llevó a cabo un estudio transversal en 320 trabajadores de la salud (TS). Se tomaron hisopados nasales y se aislaron colonias presuntivas de S. aureus. La identidad de las bacterias y su resistencia a meticilina fueron confirmadas por amplificación de los genes nuc y mec. El análisis estadístico comprendió el test de la chi al cuadrado y el test de exactitud de Fisher. De 320 TS, 96 (30%) fueron portadores nasales de S. aureus, de los cuales 20 (6,3% del total) llevaban cepas de S. aureus resistentes a meticilina (SARM) y 76 (23,7% del total) eran portadores de cepas sensibles a meticilina (SASM). La portación entre los médicos fue del 30% y estuvo dentro de los niveles publicados; dentro del subgrupo del personal técnico la portación fue superior: 57%. Se detectaron resistencias acompañantes (64,6%; 62/96) a fluoroquinolonas (24%; 23/96), aminoglucósidos (13,5%; 13/96) o macrólidos (34,4%; 33/96). Todas las cepas fueron sensibles a vancomicina y solo el 3,1% (3/96), las 3 SASM, fueron resistentes a mupirocina. Este estudio, el primero en su tipo en Argentina y uno de los pocos hechos en América del Sur, remarca la relevancia de la portación nasal de SARM y SASM en el personal de atención de la salud y evidencia la necesidad de contar con recomendaciones consensuadas para el tamizaje regular de S. aureus, así como de estrategias de descolonización.

Staphylococcus aureus is a pathogen affecting humans with a display of its ample potential to cause infections, ranging from mild to severe skin infections to life threatening infections such as endocarditis, osteomyelitis and pneumonia29, ranking as the second most common cause of hospital-acquired (nosocomial) bloodstream infections33. About 20% of patients undergoing surgery acquire at least one nosocomial S. aureus infection, leading to increased morbidity, mortality, hospital stay, and costs. Infections due to S. aureus strains could be caused by strains circulating in the community or present in hospital environments7. It is of importance to follow the evolution of resistance to antibiotics in this species, especially to β-lactams. Since resistance to other antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones and macrolides has also been detected in both types of strains, vancomycin became the last resort medication for an efficient treatment. Strains displaying methicillin resistance (MRSA) could be divided into two groups according to the origin of the infection, hospital (HA-MRSA) and community (CA-MRSA)-acquired strains; while the former strains affect mainly healthy young patients, predominantly through soft tissue infections, the latter affect older patients than those in CA-MRSA who are exposed to health care settings causing pneumonia, bacteremia, and invasive infections5. Moreover, it has been reported that a great proportion of CA-MRSA strains were mostly resistant to only one non-β-lactam antibiotics while HA-MRSA strains were resistant to two or more of those antibiotics in Argentina9. MRSA strains are highly prevalent in Latin American hospitals; in Argentina, those strains account for approximately 50% of all S. aureus isolates recovered from health care-onset infections8. It is considered that the principal route of transmission of MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) in the hospital is from patient to patient via the contaminated hands of health care workers (HCWs)28. Moreover, the main site of S. aureus carriage is the anterior nares of the nose, and carriage may be transient (hours or days) or persistent14; this carrier status has been identified as a risk factor for the development of nosocomial infections in general hospital populations32. Since it is well known that S. aureus can be found as part of the nasal microbiota without causing overt disease, this carrier state may also be an important factor for dissemination from physicians and nurses to patients and vice-versa4,6. Despite the possible role that HCWs may perform in dissemination of MSSA and MRSA strains, relatively few reports have addressed this issue25,28. With the major aim of studying the relevance of S. aureus (both MSSA and MRSA) nasal carriage, we screened the HCWs at a public general hospital serving the city of Rosario, the third largest one in Argentina. Subsequent to that, we also studied the antibiotic resistance present in the strains isolated. We herein describe our findings on both aspects.

Materials and methodsPopulation definition and studyA transversal study of the carriage of MRSA and MSSA in staff nurses, doctors and other health care personnel (n=320) was conducted at Hospital Provincial del Centenario, a general public hospital in Rosario, Argentina. The hospital has over 150 beds and its services cover different general and surgical fields including Transplant and Oncology units. From August to December 2014, participants were recruited on a voluntary basis during their regular activities. An informed consent form was made available to each participant who also completed a questionnaire regarding demographic data (sex, age, level of training and specialty as appropriate). Exclusion criteria for the population under study were the current presence of diseases compatible with S. aureus infections such as impetigo, skin and soft tissue infections, sinusitis, otitis or rhinitis, or antibiotic use within the previous three months.

Two nasal swabs (one from each nostril) were taken from each participant; samples along with questionnaires were recorded under a random number and processed at our microbiology laboratory within two hours of sampling. The samples were streaked on Chapman Agar (Britania, Buenos Aires, Argentina) plates which were then incubated at 37°C for 48h. Mannitol-positive colonies were re-streaked on nutrient agar (Difco, Sparks, USA) plates at 37°C for 24h. Isolated colonies were analyzed by Gram stain and colonies compatible with S. aureus were tested for coagulase and catalase production by standard microbiological protocols. Isolates that were catalase-positive and coagulase-positive were taken presumptively as S. aureus.

All the strains were tested for their antibiotic susceptibility according to the current guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) on Müeller Hinton Agar (Britania, Buenos Aires, Argentina) plates1. Methicillin resistance was evaluated by using cefoxitin disks (30μg) (Britania, Buenos Aires, Argentina). Mupirocin resistance was tested according to Fuchs et al.12 using 10μg mupirocin disks. Resistance to penicillin was assayed only in MSSA strains according to CSLI1 using 10 U penicillin disks (Britania, Buenos Aires, Argentina); in the resistant strains the presence of β-lactamases was detected using DiaTabs (Diagnostic Tablets for Bacterial Identification, Rosco Diagnostica, Taastrup, Denmark). Resistance to macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramins was established by the double disk method (D-test) as described elsewhere1. The susceptibility to glycopeptides was determined by a prediffusion method8,26 using tablets for vancomycin (30μg) and teicoplanin (30μg) (Rosco Diagnostica, Taastrup, Denmark).

Molecular biology techniquesThe identity of the isolates presumptively identified as S. aureus and their methicillin resistance (MetR) were confirmed by multiplex PCR, using DNA extracted from isolated colonies as template according to Louie et al. using the primers described therein18. The expected sizes of PCR products are as follows: 798bp (16S rRNA gene); 533bp (mecA) and 270bp (nuc). Products were separated by standard agarose gel electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide (0.3μg/ml) visualized and photographed under UV light. PCR product size was estimated by comparison to a 100bp molecular weight marker (Embiotec, Buenos Aires, Argentina).

Statistical analysisp-values for the variables analyzed in each case were calculated by the Fisher exact test and the Chi square test; considering a p-value <0.05 as significant.

The Ethics Committees of the Universidad Nacional de Rosario and Hospital Provincial del Centenario approved the study protocol.

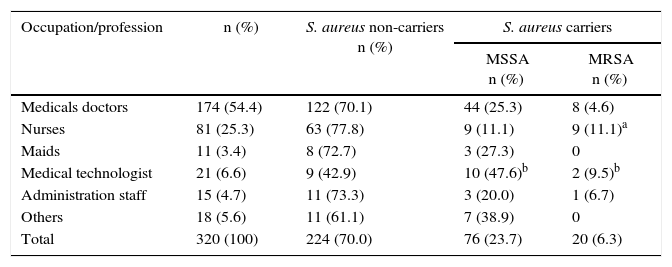

ResultsDistribution of S. aureus carriers in HCWsThe population under study (n=320) was significantly biased by gender with a predominant female fraction of 69.7%. HCWs were grouped into three age ranges, 20–29, 30–39 and over 40 years old (37.5%, 36.6%, 25.9%, in each group). The distribution by occupation showed a large fraction of physicians (54.4%), followed in importance by nurses (25.3%); other roles such as technicians (6.6%), clerks and administrative staff (4.7%), and other HCWs (nutritionists, psychologists, chiropractors, janitors, maids, hospital orderlies and others) representing 9%.

The screening for nasal carriage of S. aureus revealed the presence of this bacterial species in 30% of the volunteers. In only three services (3/24), the personnel was found to be free of S. aureus nasal carriage, stressing the widespread presence of this bacterium in the hospital. The distribution of carriage according to duties showed that 30% of the medical doctors (52/174) and 22% of nurses (18/81) carried S. aureus, the difference was not statistically significant according to the Chi square and the Fisher exact tests (p>0.05). However, the largest subpopulation of positive carriers was the one of medical technologists – those working in operating rooms, chemotherapy and medical imaging – (12/21; 57.1%); this difference was statistically significant according to the Fisher exact test (p<0.05) (Table 1). This high value contrasts with the relatively low positive carriage shown by administration staff, janitors and hospital orderlies, subpopulations that are also in direct contact with patients (Table 1).

Distribution of nasal S. aureus carriage by occupation

| Occupation/profession | n (%) | S. aureus non-carriers n (%) | S. aureus carriers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSSA n (%) | MRSA n (%) | |||

| Medicals doctors | 174 (54.4) | 122 (70.1) | 44 (25.3) | 8 (4.6) |

| Nurses | 81 (25.3) | 63 (77.8) | 9 (11.1) | 9 (11.1)a |

| Maids | 11 (3.4) | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | 0 |

| Medical technologist | 21 (6.6) | 9 (42.9) | 10 (47.6)b | 2 (9.5)b |

| Administration staff | 15 (4.7) | 11 (73.3) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (6.7) |

| Others | 18 (5.6) | 11 (61.1) | 7 (38.9) | 0 |

| Total | 320 (100) | 224 (70.0) | 76 (23.7) | 20 (6.3) |

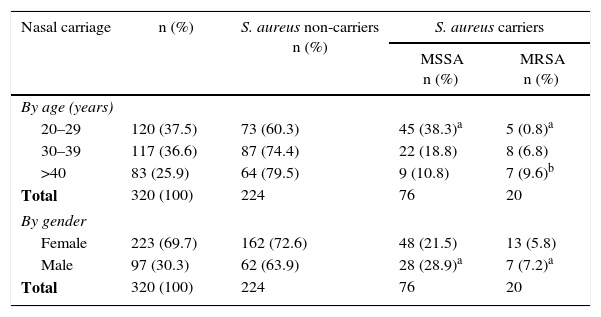

Phenotypic and genotypic analysis determined that 20.8% (20/96) of all S. aureus isolates were MetR (Figure S1); distribution by duties revealed that medical doctors and nurses carrying S. aureus were found to be positive for MRSA carriage (8/52 and 9/18 respectively) followed by medical technologists (2/12) and administration staff members (1/4) (Table 1). Moreover, nurses are more frequent carriers of MRSA than physicians at a statistically significant percentage as shown by the Fisher exact test (p<0.05, Table 1). Statistical analysis using the Chi square and the Fisher exact tests with age and sex as variables showed that there was a statistically significant correlation between S. aureus nasal carriage and age and sex, being predominant the 20–29 year old group over the other age groups and in male over females (p<0.05 in both cases) in agreement with the literature20,21. Carriage of MRSA strains was higher in the oldest group (>40 years old) according to the Fisher exact test (p<0.05) (Table 2).

Distribution of S. aureus nasal carriage by age and sex

| Nasal carriage | n (%) | S. aureus non-carriers n (%) | S. aureus carriers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSSA n (%) | MRSA n (%) | |||

| By age (years) | ||||

| 20–29 | 120 (37.5) | 73 (60.3) | 45 (38.3)a | 5 (0.8)a |

| 30–39 | 117 (36.6) | 87 (74.4) | 22 (18.8) | 8 (6.8) |

| >40 | 83 (25.9) | 64 (79.5) | 9 (10.8) | 7 (9.6)b |

| Total | 320 (100) | 224 | 76 | 20 |

| By gender | ||||

| Female | 223 (69.7) | 162 (72.6) | 48 (21.5) | 13 (5.8) |

| Male | 97 (30.3) | 62 (63.9) | 28 (28.9)a | 7 (7.2)a |

| Total | 320 (100) | 224 | 76 | 20 |

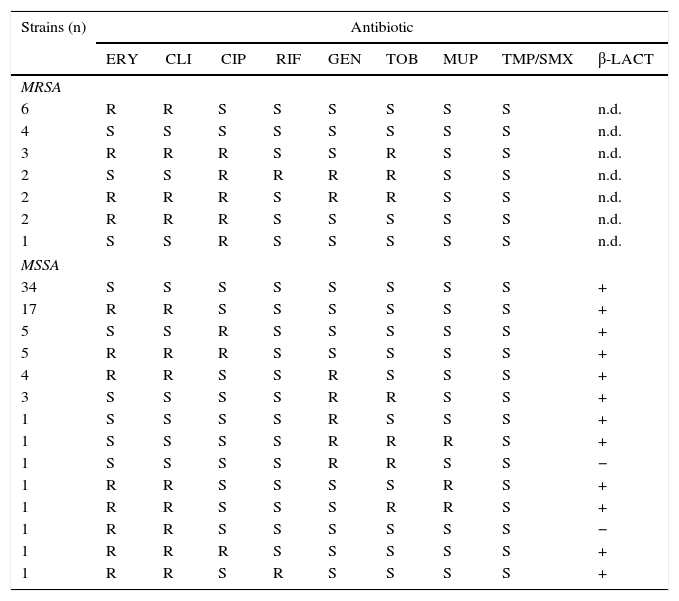

Although a major aim of this study was the detection and quantification of MSSA and MRSA carriage in HCWs in a public hospital, it is of no lesser importance to address the issue of accompanying resistance to other antibiotics.

Of the MRSA isolates analyzed, 10 out of 20 were also resistant to ciprofloxacin, while 13 out of 20 showed resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin with constitutive 9/13 or inducible 4/13 phenotypes. Resistance to rifampicin (2/20), gentamicin (4/20) and tobramycin (7/20) was also detected but at lower levels (Table 3).

Phenotypic analysis of antibiotic resistance of S. aureus isolated in this study

| Strains (n) | Antibiotic | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERY | CLI | CIP | RIF | GEN | TOB | MUP | TMP/SMX | β-LACT | |

| MRSA | |||||||||

| 6 | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | n.d. |

| 4 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | n.d. |

| 3 | R | R | R | S | S | R | S | S | n.d. |

| 2 | S | S | R | R | R | R | S | S | n.d. |

| 2 | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | S | n.d. |

| 2 | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | n.d. |

| 1 | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | n.d. |

| MSSA | |||||||||

| 34 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | + |

| 17 | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | + |

| 5 | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | + |

| 5 | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | + |

| 4 | R | R | S | S | R | S | S | S | + |

| 3 | S | S | S | S | R | R | S | S | + |

| 1 | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | + |

| 1 | S | S | S | S | R | R | R | S | + |

| 1 | S | S | S | S | R | R | S | S | − |

| 1 | R | R | S | S | S | S | R | S | + |

| 1 | R | R | S | S | S | R | R | S | + |

| 1 | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | − |

| 1 | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | + |

| 1 | R | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | + |

n.d=not determined.

R and S correspond to resistant and susceptible strains, respectively. ERY, erythromycin; CLI, clindamycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; RIF, rifampicin; GEN, gentamicin; TOB, tobramycin; MUP, mupirocin; TMP/SMX, sulfomethoxazol-trimethroprim; β-LACT, β-lactams.

Most MSSA isolates were positive for β-lactamases as expected (74/76, 97.4%) and also revealed high frequency of erythromycin and clindamycin resistance (31/76, 40.8%) of which an inducible phenotype was detected in 25 out of 31 isolates (80.6%) and a constitutive phenotype was detected in 6 samples (19.4%). Furthermore, resistance to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin was 12 and 13%, respectively. Only 1 out of 76 (1.3%) of MSSA strains was resistant to rifampicin. The presence of resistance to multiple antibiotics was less important in this group (64/76, 84.2%) strains showing either pan-susceptibility or resistance to only one of the antibiotics tested. Moreover, all MSSA and MRSA isolates were fully susceptible to vancomycin and sulfomethoxazole-trimethroprim. Likewise, mupirocin was equally active against both S. aureus isolates except for three MSSA strains that were resistant (Table 3). Statistical analysis showed that the presence of resistance to two or more antibiotic groups was more common in MRSA strains than in MSSA strains (p<0.0001 by the Fisher exact test).

DiscussionMost of the literature on the molecular analysis of world-wide S. aureus prevailing clones focuses on their carriage among patients at very specific age groups or health conditions or at settings of different nature such as tertiary age care, pediatric units, etc.3,15,31. Similarly, comparable studies performed in Argentina so far have also focused on patients as the subjects of the study9,11,17,27. There is a paucity of information on the role of human carriage among HCWs, personnel that could easily carry and spread S. aureus strains to patients28. An overview of the published work highlights that carriage of MSSA or MRSA in HCWs occurs at a variable rate in countries with very different public health and social structures, however, there is no simple way to predict carriage rates on the basis of the mentioned variables10,22,24. Our study of nasal carriage in HCWs in a local public hospital showed that 30% of the personnel carried S. aureus, of whom 6.3% accounted for MRSA; those frequencies are comparable to others reported in the literature, i.e., in a recently published study carried out in a tertiary care hospital in Perú, a total S. aureus carriage of 22.7% was detected, of this percentage, 8.7% was characterized as MRSA13. Interestingly, we detected a statistically significant proportion of medical technologists – including those working in operating rooms – carrying S. aureus in their nares, a situation that has a direct impact on the possibility of spreading those colonizing strains to inpatients during the surgery; second and third to that group were medical doctors (30%) and nurses (22%). with no statistically significant difference between them. Remarkably, nurses were mainly colonized by MRSA strains rather than MSSA strains (statistically significant, p<0.005 by the Fisher's exact test) than medical doctors.

Upon our detection of MRSA and MSSA carriage, we determined the frequency of accompanying resistances, finding higher levels of fluoroquinolone resistance in MRSA strains (10/20) compared to MSSA (11/76); those values were statistically significant (p<0.05, Fisher exact test). Macrolide resistance showed non-statistically difference (p>0.05) between MRSA and MSSA (13/20 and 31/76, respectively). Resistance was also detected for rifampicin and aminoglucosides at low level without statistically significant difference between MRSA and MSSA strains (p>0.05). The analysis of antibiotic resistance profiles in both MSSA and MRSA clearly showed that macrolides have lost a great deal of efficacy; however, importantly, susceptibility to sulfomethoxazole-trimethroprim and vancomycin is still intact. Interestingly, an unrelated but similar study performed on medical students (n=233) of our institution by another research group, revealed values comparable to the ones we found for HCWs, with 23.6% of S. aureus nasal carriage, 6.8% of which was MRSA; however there is a large difference in resistance to macrolides, being much more reduced (3% constitutive expression and 15% inducible expression) in that study than in our study. This again may reflect the different antibiotic usage in the different groups under analysis19.

Finally it is worth mentioning that we found very few MSSA strains displaying resistance to mupirocin (3/76), while all the MRSA were fully susceptible. There is no consensus on whether a decolonization strategy should be applied when nasal carriage of MRSA is detected. Although there are biocides such as chlorhexidine that may be used for this purpose, mupirocin is the most commonly used topic decolonizing agent due to its little cost and efficacy16,30. Resistance to this compound has been reported but it does not develop at high frequency23. Although this may suggest that its use does not place a strong selective pressure, it is of relevance to consider the need to set up guidelines for its use in hospitals and health care centers.

In summary, the screening of nasal carriage of S. aureus by staff members at a public hospital in Argentina revealed that 30% of its personnel was positive for this bacterium, 6.3% of whom was also MRSA. As no resistance to sulfomethoxazole-trimethroprim or vancomycin was detected on the MRSA strains studied, those drugs (being sulfomethoxazole-trimethroprim the first option) are good therapeutic choices in case those strains were transmitted to patients in the hospital environment. Based on the chance of person-to-person transmission, routine nasal screening and decolonization strategies should be considered by health care providing institutions. However, in order to have a complete view of the scenario of S. aureus carriage in this population, and the efficacy of the suggested control strategies, the dynamics of intermittent vs. persistent carriage should be addressed through a longitudinal study. In this perspective, a recent publication shows the importance of host heterogeneity (persistent and intermittent carriers depending on the length of carriage) in the correct mathematical modeling of possible S. aureus transmission2. Therefore, that factor should also be included to avoid systematic errors in the predictions of the effects of intervention strategies. Our report sets up the baseline for studying nasal carriage in local HCW; thus, further research is warranted.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors state that the procedures followed conformed to the ethical standards of the responsible human experimentation committee and in agreement with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the correspondence author.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by a grant from ANPCyT (Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica, Argentina; PICT 1406). We would like to thank to Dr. Nora Martín for her excellent technical assistance, Dr. Juan Pablo Scapini and Dr. Gerardo Leotta for advice and strains. We thank advanced M.D. students Laura Crognolleti, Antonella Cipollone and Melissa Calderon for sample collection and strain isolation.