This study assessed if the healthcare system overload and the organizational changes made in response to COVID-19 may be having an impact on clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the peritonsillar infection (PTI).

Materials and methodsIn a retrospective longitudinal and descriptive follow-up, we reviewed the circumstances of the patients attended during 5 years, from 2017 to 2021, in two hospitals, one regional and other tertiary. Variables related to underlying pathology, history of tonsillitis, time of evolution, previous visits to Primary Care, diagnostic findings, abscess/phlegmon ratio, and length of hospital stay were recorded.

ResultsFrom 2017 to 2019, the incidence of the disease ranged between 14 and 16 cases/100,000 inhabitants-year, and decreased to 9.3 in 2020, a 43% less. Patients with PTI consulting in pandemic time were visited much less often in Primary Care services. They showed a greater severity of symptoms and the period of time between their appearance and diagnosis was longer. Additionally, there were more abscesses and the need for hospital admission greater than 24h was 66%. There was hardly a causal relationship with acute tonsillitis, although 66% of the patients evidenced history of recurrent tonsillitis, and 71% concomitant pathology. All these findings showed statistically significant differences with the pre-pandemic cases.

ConclusionsThe protection of airborne transmission, the social distancing and the lockdown adopted in our country are measures that seem having been able to modify the evolution of PTI, with a much lower incidence, a longer recovery period and a minimal relationship with acute tonsillitis.

Este estudio trata de valorar la repercusión de la pandemia sobre la incidencia y la evolución clínica de la infección periamigdalina (IPA).

Material y métodosRevisamos en un seguimiento longitudinal y descriptivo retrospectivo las circunstancias de los pacientes atendidos durante 5 años, de 2017 a 2021, en dos hospitales, uno comarcal y otro terciario. Se registraron variables relacionadas con la patología de base, antecedentes de amigdalitis, tiempo de evolución, visitas previas en Atención Primaria, hallazgos en el diagnóstico, relación absceso/flemón y días de estancia hospitalaria.

ResultadosDe 2017 a 2019 la incidencia de la enfermedad osciló entre 14 y 16 casos/100.000 habitantes-año, pero en 2020 se redujo a 9,3, un 43% menos. Los pacientes con IPA que consultaron en pandemia generaron pocas visitas previas en servicios de Atención Primaria, presentaron mayor severidad de los síntomas y mayor demora en el diagnóstico. Además, hubo más abscesos que flemones y la necesidad de ingreso hospitalario superior a 24h fue del 66%. Apenas hubo causalidad con amigdalitis agudas, aunque el 66% de los pacientes padecía amigdalitis de repetición, y el 71% patología concomitante. Todos estos hallazgos mostraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas respecto a los casos prepandemia.

ConclusionesLa protección de la transmisión aérea, el distanciamiento social y el confinamiento adoptados en nuestro país son medidas que han podido modificar la evolución de la IPA, con una incidencia muy inferior, un período de recuperación mayor y mínima relación con amigdalitis aguda.

The repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare in our country have been clear. The need to reassign human and material resources while establishing a specific order of care for patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection markedly reduced the availability of Primary Care personnel for the rapid detection of acute pathology in many specialities.1,2

Peritonsillar infection (PTI) is an ENT emergency which used to be first detected in health centres. Nevertheless, the protection and safety protocols for medical personnel during the pandemic restricted the maneouvres involved in inspecting the upper aerodigestive tract.2–4

The overload in these centres due to the organizational changes implemented may also have affected the care of patients with PTI, which was underestimated or less controlled.5 It is also possible that the fear of catching the infection in the street or hospital environments led patients to delay seeking care, thereby facilitating the progression of the disease due to the absence or ineffectiveness of treatment. This circumstance has already been documented,3,6 and it is clear that in our country the lack of medical staff led to a slowdown in care during the pandemic. This in turn gave rise to modifications in the behaviour of pacientes, healthcare professionals and even the diseases themselves.1,5

The unexpected magnitude of the pandemic in our sector consumed a large number of human and material resources. It undoubtedly affects the surgical and out-patient waiting lists in our speciality. Although emergency hospital ENT in Spain seem to have withstood the pressure of the demand for attention, countries such as the United Kingdom have designed contingency plans to refer the treatment of peritonsillar absesses to an intermediate or out-patient level of healthcare.4,7

In the light of the above considerations, we find it interesting and useful to evaluate whether variations have arisen in the medical circumstances of the patients seen in our area for PTI over recent years. This review was developed to describe and analyse their clínical and epidemiological characteristics, as well as any eventual modifications during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and methodsA longitudinal and descriptive retrospective study was carried out of pacientes diagnosed and treated for PTI from January 2017 to December 2021. The computerized records of the participating hospitals were used for this purpose. One hospital is regional and the other is its tertiary referral hospital, with a catchment area of 480,000 inhabitants. 336 episodes were recorded during the period of time in question.

The diagnosis of PTI was based on anamnesis and physical examination, which were always carried out by an ear, nose and throat doctor. 23 specialists took part during the period under study, of which 18 did so during at least 3 years. Abscesses were differentiated from inflamed areas by obtiaing pus by puncture–aspiration during the visit, which is considered to be the test of choice for diagnosis.8,9 The following clinical variables were recorded:

- •

Age and sex.

- •

Concommitant basal pathology.

- •

A history of repeated tonsillitis.

- •

Connection with symptoms of acute tonsilitis.

- •

Episodes of previous inflamations/abscesses.

- •

Days of evolution until diagnosis.

- •

Medical care and the prescription of antibiotic therapy in a primary care centre prior to diagnosis.

- •

Signs and symptoms at the moment of diagnosis.

- •

Classification as inflamation or abscess by means of puncture–aspiration.

- •

Days of hospitalization when admission occurred.

- •

Recurrences of the process.

Patients were excluded from the study when these data were lacking. The therapeutic options chosen were the same in both Health Departments. The protocol used in our departments to manage PTI was applied to all of the pacientes treated. The recommendation was to drain accumulated fluid if any were present, hospitalization for antibiotic therapy, corticoid thereapy and intravensous analgesia – including admission for observation in the emergency ward during a period of hours to receive these treatments, considering out-patient minor surgery as hospitalization –. During the periods of maximum hospital occcupation and over-crowding of the wards, it was suggested to the pacientes who showed a clear clinical improvement following drainage and the first dose of intravenous treatment that they should be discharged and visit the out-patient surgery after 48h for reassessment. If the patient rejected admission, this treatment was administered orally in their home.

Patients were discharged based on the criteria of a clinical improvement and laboratory findings. Data analysis was undertaken using the SPSS 27.0 statistical package for Windows. The ANOVA-test was used to compare several measurements of quantitative variables with normal distribution of the information, independently of the cases and equality of varience. Chi-squared distribution was selected for random independent variables with a standard normal distribution, expressed as a ratio.

The lineal regression model was used to correlate two quantitative variables, to approximate the relationship of dependency between a dependent factor and other independent ones with a random term, calculating the equation of regression lines and the R correlation coefficient to determine the quality of fit. Any comparison where P<0.001 was considered to be a statistically significant difference.

ResultsIn the 5 years that were reviewed, 10 cases were excluded as they lacked the required data on anamnesis or clinical findings. The clinical manifestations and examination findings are shown in Table 1. This shows that the most common symptom was sore throat that occurred spontaneously or when swallowing, reflex otalgia, dysphagia, as well as asymmetry in the veil and/or pillars found in clinical examination. All of these symptoms affected more than 90% of the diagnosed pacientes. The rarest alterations detected were glositis, the feeling of dyspnoea, dysphonia and cervical spasms,which affected less than one quarter of the group.

Clinical manifestations and findings recorded in the anamnesis and examination of the pacientes who visited due to peritinsillar infection, and the percentages in which they appeared.

| Manifestations and findings | % |

|---|---|

| Sore thorat | 96.2 (306) |

| Odinophagia–dysphagia | 94.6 (301) |

| Reflex otalgia | 93 (295) |

| Veil-tonsillar asymmetry | 90.5 (288) |

| General discomfort | 79.5 (253) |

| Pain on veil pressure | 71 (226) |

| Sialorrhea–drooling–choking | 68.8 (219) |

| Trismus | 63.5 (202) |

| Pharyngolalia | 63.2 (201) |

| Uvula displacement | 47.4 (151) |

| Uvula oedema | 44.9 (143) |

| Slight fever–fever | 37.4 (119) |

| Reactive cervical adenitis | 32 (102) |

| Halitosis | 29.2 (93) |

| Cough | 21 (67) |

| Uni/bileral purulent tonsillitis | 13.2 (42) |

| Furred–depapillated–scalded tongue | 8.1 (26) |

| Dyspnea | 7.2 (23) |

| Dysphonía | 5.9 (19) |

| Cervical pain/contracture-torticollis | 5 (16) |

| Other speed problems | 2.8 (9) |

The % resulting from the coefficient between cases in which the manifestation was detected and the total volume of episodes studied (n=318).

Table 2 shows the interannual evolution of the clinical peculariaties and chronobiological aspects of the subjects with PTI. The number of PTI cases seen in the 3 years before the COVID-19 pandemic increased gradually with an incidence that rose to 15.1/100,000 inhabitants-year, although this fell to 10.4 in the first 2 complete yeatrs of the pandemic. In fact, the annnual incidence fell by 43% from 2019 to 2020. In 2021 a tendency for the number of cases to rise seemed to exist. No paciente treated for peritonsillar inflammation or abscess had acute infection by COVID-19 at the moment of diagnosis. No significant variations were found according to the sex or age of the pacientes, although the subjects seen after the start of the pandemic had a higher average age.

Interannual evolution of the clinical and epidemiological data of all the patients included in the study.

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 67 | 72 | 79 | 45 | 55 | 318 |

| Case incidence/inhabitants-year | 13.9 | 15 | 16.4 | 9.3 | 11.4 | 13.2 |

| No. cases COVID+ | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No. of pacientes | 62 | 66 | 74 | 45 | 54 | 301 |

| No. of pacientes with ≥2 episodes | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Age (years) | 29.6±12.7 | 22.7±11.9 | 28.3±14.8 | 36.3±15.3 | 34.1±13.2 | 28.9±13.1 |

| M/F sex ratio | 1.16 (36/31) | 0.94 (35/37) | 1.19 (43/36) | 1.25 (25/20) | 0.83 (25/30) | 1.06 (164/154) |

| Days of symptims prior to admission | 3.2±1.8 (1–10) | 4.3±2.3 (1–9) | 3.9±2.5 (1−12) | 5.7±3.0 (1−13)* | 4.5±2.5 (1−10) | 4.4±2.6 (1−12) |

| No. visits/pat. to Primary Care before diagnosis | 2.1±1.2 (0–5) | 1.6±0.9 (0–4) | 2.1±0.7 (0–4) | 0.5±0.6 (0–2)* | 1.2±1.2 (0–4)* | 1.3±1.1 (0–5) |

| No. of cases with ATB treatment prior to diagnosis | 7 (10%) | 10 (13%) | 8 (10%) | 2 (4%) | 5 (9%) | 32 (10%) |

| Cases that visited hospital directly | 5 (7%) | 10 (13%) | 9 (11%) | 23 (51%)* | 16 (29%) | 63 (20%) |

| Days of hospitalization | 1.1±0.7 (0–3) | 1.2±0.6 (0–3) | 1.1±0.5 (0–2) | 1.9±1.7 (0–13)* | 1.4±0.8 (0–4) | 1.3±1.0 (0–13) |

| No. cases admitted ≥24h. | 9 (13%) | 15 (20%) | 12 (15%) | 30 (66%)* | 17 (30%) | 83 (26%) |

| Abscess/inflammation ratio | 1.23 (37/30) | 1.05 (37/35) | 1.39 (46/33) | 3.09 (34/11)* | 2.92 (41/14)* | 1.58 (195/123) |

| No. items manifestation-findings* | 6.8±4.7 | 6.2±5.8 | 5.8±5.7 | 11.9±7.3* | 8.1±5.8 | 6.9±6.0 |

| Cases with concomitant pathology | 29 (43%) | 22 (30%) | 31 (39%) | 32 (71%)* | 35 (63%)* | 149 (46%) |

| Cases with previous tonsillitis | 23 (34%) | 23 (31%) | 26 (32%) | 5 (11%)* | 15 (27%) | 92 (28%) |

| Cases with a history of repeated tonsillitis | 24 (35%) | 22 (30%) | 22 (27%) | 30 (66%)* | 26 (47%) | 124 (38%) |

Clinical manifestations and findings are shown in Table 1.

ATB: antibiotic; M: male; F: female.

Furthermore, once the pandemic had commenced in our country the patients who were diagnosed had more symptoms and the results of examination were more emphatic, as is shown by the fact that a significantly higher number of clinical items were found then in comparison with previous years (an average of 6/paciente in 2017, 2018 and 2019 vs. 12/paciente in 2020). The number of individuals with PTI who visited the hospital emergency services directly without first having been seen by Primary Care rose from 11% in 2019 to 51% in 2020. The percentage of pacientes who had already started antibiotic treatment prior to diagnosis was lower during the pandemic, although without statistically significant differences in comparison with previous years. Moreover, in 2020 the average period of time with symptoms prior to diagnosis was longer than 5 days, the longest of all the years studied, and the duration of hospitalization in pacientes with PTI in the years of the pandemic was also longer – two thirds of the subjects treated in 2020 required more than 24h before being discharged, as opposed to 15% in 2019 –. These values were always found to be statistically significant when they were compared to the 3 previous years.

What is more, in the first year of the pandemic patients with PTI had a significantly higher percentage of concomitant basal pathology in comparison with the patients treated before the pandemic. Likewise, those treated during the pandemic (in 2020) showed less association with having suffered acute tonsillitis, although their history of repeat tonsillitis was far more pronounced than it had been in previous years. Finally, presentation was far more common in the form of a peritonsillar abscess during the pandemic. All of these differences were foujnd to be statistically significant.

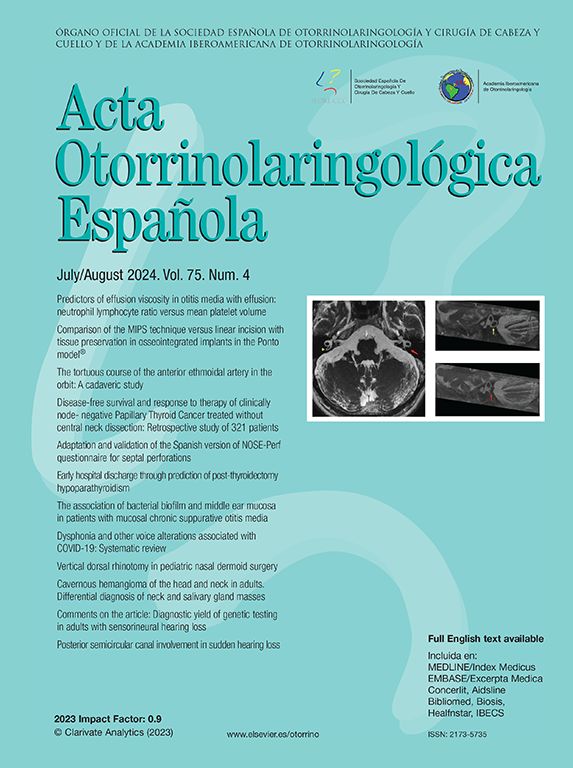

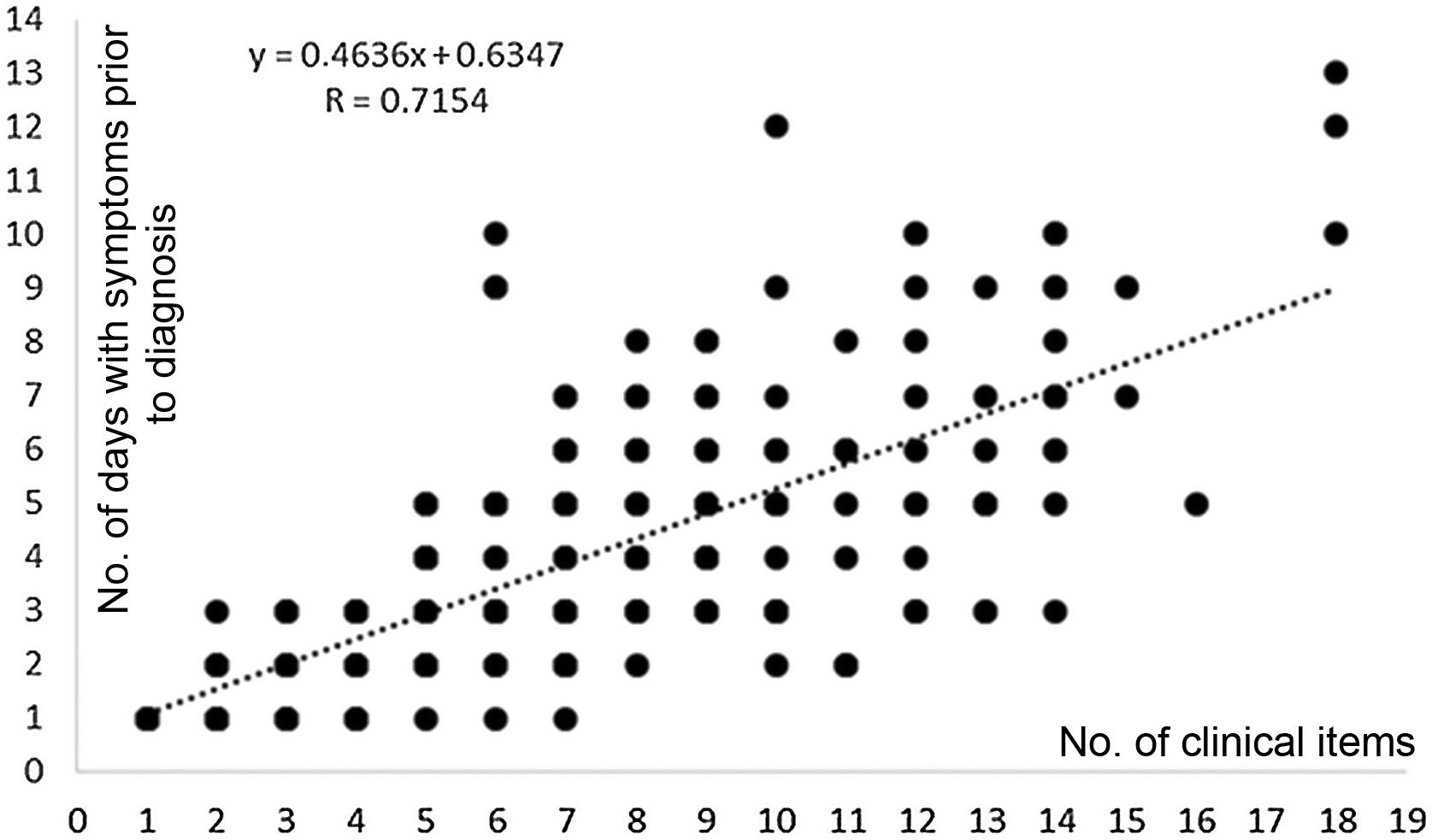

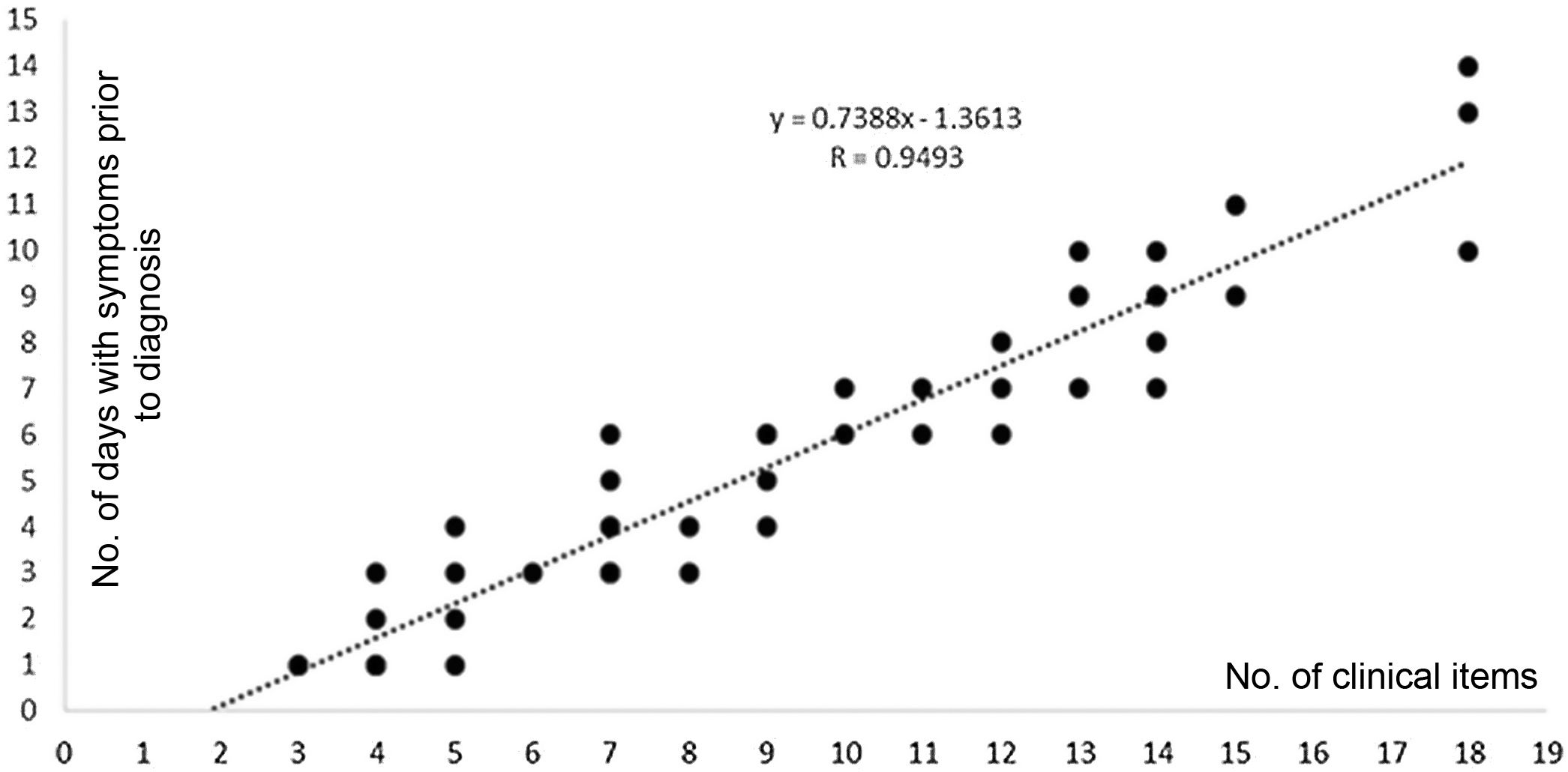

The lineal regression model for the quantitative variables that were tested (age, number of days with symptoms, visits to Primary Care before diagnosis, duration of hospital stay and number of clinical items recorded at the moment of the definitive diagnosis) showed very low R correlation coefficents. A positive tendency was only detected when the number of clinical items detected were paired with the number of days patients had symptoms prior to diagnosis in the 5 years reviewed, although this relationship was not statistically significant, with R=0.7154 (Fig. 1). When this model was applied to the same variables in 2020 it was found to be statistically significant, with R=0.9493 and P<0.001 (Fig. 2), while in 2021 the correlation coefficient was equally high but not decisive, where R=0.836 (Fig. 3).

Lineal regression line and equation obtained by correlating the quantitative variables “No. of clinical items” (abscisses) and “No. of days with symptoms prior to diagnosis” (ordinates) durint the períod from 2017 to 2021, both inclusively. A positrive tendency that was not statistically significant.

Lineal regression line and equation obtained by correlating the quantitative variables “No. of clinical items” (abscisses) and “No. of days with symptoms prior to diagnosis” (ordinates) in 2020, the first year of the pandemic in Spain. A stasticially significant positive tendency.

Lineal regression line and equation obtained by correlating the quantitative variables “No. of clinical items” (abscisses) and “No. of days with symptoms prior to diagnosis” (ordinates) in 2021, the second year of the pandemic in Spain. A positrive tendency that was not statistically significant.

The clinical signs of PTI and exploratory findings usually make it possible to establish the diagnosis in the first visit. On the other hand, it is also important for patients to visit at an early stage, given the likelihood of an inflammation evolving into an abscess and progress to deep cervical levels if treatment is delayed or incorrect. It is therefore important to optimize resources, training and fluidity of communication between Primary Care and ONT specialists.

Although the incidence of the disease falls within a broad range of from 5 to 50 cases per every 100,000 inhabitants and year,9–11 our records indicate that the volume of pacientes treated for PTI has fallen since the pandemic started (by 43% from 2019 to 2020), and other series consulted have also shown this.10,12,13 A reasonable explanation for this would be the fact that infection by SARS-CoV-2 and PTI share the same mechanism of respiratory transmission by the emission of aerosoles and droplets with a diameter of from 5μm to 10μm. The social and medical actions implemented to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (the use of masks, social distancing and lock-down at home) surely also restricted the spread of PTI. Allen et al. found that the incidence of tonsillitis fell almost to the point of disappearing from 2019 to 2020.14 The number of urgent visits to the departments within the speciality also seem to have fallen during the pandemic,7,13,15 and governments with solvent health services did not restrict emergency access for pacientes with acute ENT pathology. Some authors find an explanation not only in the lack of appropriate healthcare, with unplanned closures of health centres, as they also take into account the acquired relcutance of the population to visit health facilities, together with the effectiveness of telephonic visits in ENT.13,16

Clinical findings and the results of physical examination of pacientes with PTI became more negative after the beginning of the pandemic. Due to the work overload in Primary Care centres and the development of the telephonic medical service, the first visit to these patients in a hospital environment took place later. This explains why there are more abscesses than inflammations, with clinical symptoms that have progressed further and also increased in number. The fact that this population has a very low prescribing rate for antibiotics is striking.

We find that sore throat, dysphagia–odinophagia, veil-tonsil assymetry, sialorrhea, pharyngalgia and trismus are very common in almost all of the series.9–11,15 Although the gathering of clinical information is often subject to a subjective element that depends on the patient and the doctor, the symptoms in general are intense and simultaneous, although in percentages which vary from those supplied by other authors, although agreeing with them in that detection does not necessarily involve the presence of accumulated fluid.7,9,11,17 Nevertheless, in 2019 the United Kingdom drew up the first predictive index of a peritonsillar abscesss based on the presence of unilateral throat pain, trismus, a pharyngolalic or “hot potato” voice and deviation of the uvula.18 This seems to have been validated during the pandemic wihtout including oral examination when identifying patients without including oral examination when identifying patients with velopharyngeal supurating accumulations.17

When the SARS-CoV-2 infection started the amount of antibiotics prescribed to partients with PTI fell, and these patients were also characterized by first visiting a hospital emergency service and having a longer average hospital stay, which is congruent with the increased severity of their symptoms. The statistically significant differences in these variables that were found in our study in comparison with previous years lead us to consider that there were major defects in the offer of care at primary level. These defects have been widely documented: urgent face-to-face visits were imposssible, diagnosis was by telephone and examinations of the upper airways were not very exhaustive.2,3,5

Due to the above considerations, in 2020 and 2021 the Sociedad Española de Otorrinolaringología y Patología Cérvico-Facial published specific recommendations, considering pacientes with PTI as surgical emergencies, without restricting their access to healthcare resources and emphasising the use uniforms and protective equipment, with anaesthesia by infiltration, drainage by incision without using an electric scalpel and admission in major out-patient surgery regime when possible.19 Under these conditions, only pacientes in the poorest general health would be admitted to hospital, and this without doubt prolonged their average stay.

Hospital admissions lasted for significantly longer during the pandemic than was the case beforehand. Some cases even needed more than 10 days before they oculd be discharged. This lengthening of hospitalization does not correlate well in the logistic regression model used with either the intensity or the duration of symptoms, or with the number of visits patients may have made to their general practicioner before a definitive diagnosis was established. We believe that other parameters shown in the evolution table may have an influence here. In 2020 the abscess/inflammation ratio of the pacientes rose to 3.09, while it had been 1.39 the previous year. It is highly posisble that the interventionist therapeutic option selected in these cases, puncture and/or drainage, had to be repeated because it was insufficient or incomplete, requiring a cervical approach in complicated cases. This year was by far the one with the highest number of patients with PTI and other concomitant pathologies such as diabetes, asthma, environmental allergies, kidney failure or autoimmune disorders. This meant that patients’ clinical condition evolved slowly. Other actions may have also been necessary, such as tolsillectomy or the stabilizationof metabolic pathologies or chronic diseases, and this too meant that hospitalization had to be prolonged.

In 2012 Costales et al. documented their protocol for action in 100 consecutive cases of peritonsillar inflammation and abscess. They state that they see no need for drainage, as puncture-aspiration is sufficient together with a few hours of intravenous therapy and follow-up at home and as out-patients to resolve the problem,9 which is closer to the North American form of treatment.11 Europe in general had not agreed this proposal then. However, in March 2020 the United Kingdom, a counry which was strongly impacted by COVID-19 and subsequent hospital deficiencies, published national rules for practice when examining the upper respriatory-alimentary tracts, advising against unnecessary procedures.20 This is very similar to the previous Spanish proposal. Smith et al. state that they found a very satisfactory response to this in their multicentre review of 12 weeks in 2020 of 83 hospitals and 418 cases of PTI. Nevertheless, their main objective was to confirm the reliability of the intravenous administration of corticoids and antibiotic in comparison with drainage of the abscesss as a tool to reduce the number of admissions, due to the limited resources of Primary Care.21 In general, the authors who have adopted this approach find that the symptoms do not reappear.7,21,22

Given these preventive measures, at the start of the pandemic only a small percentage of patients with a peritonsillar abscess or inflammation mentioned any link with a previous episode of tonsillitis, while in previous periods this link existed for one third of patients. The lack of influence of acute tonillitis on the menhanism which causes PTI seems to be confirmed, with increased aetiopathogenic involvement of other factors, such as smoking, Weber gland obstruction or oxidative stress in lymphoid tissue.10,23,24

We believe that this follow-up offers a complete report on the evolution of PTI before and during the pandemic. The marked interruption in routine and proximity healthcare seems to have led to variations in the clinical and social behaviour of patients with this infection. The work is compact and complete, as it uses data from the protocolized working of 23 specialists during 5 consecutive years, exactly at a moment that as historical as it was unforeseeable. This study did not aim to collect information on physiological or laboratory parameters, selection techniques or algorithms for working.

Reducing the use of emergency services by improving access to Primary Care units is a long-term objective. This was first mentioned in the pioneering work by Shortliffe et al. in Hartford Hospital in 1958,25 as they found that only a small number of patients who visited the emergency department required hospital care. At the time the proposed solutions were to promote the use of out-patient care and educate pacientes about seeking a preliminary treatment with their family doctors. It is possible that the outbreak of COVID-19 will move our current society in a similar direction. Although it is true that the current priority is to fight the pandemic, many aspects of medical care will have to be revised over time.

ConclusionsThe COVID-19 pandemic had a significant repercussion on the cases of PTI seen by ear, nose and throat specialists in emergency departments. They were found to be delayed, probably due to the reluctance of the population to visit as well as the limited access to primary medical care services, all of which were due to the measures taken to achieve social isolation. Although the number of cases which required hospital treatment fell significantly thanks to the preventive measures against SARS-CoV-2, it is also true that the cases seen had symptoms which had developed further, already in abscess phase and with more comorbidity and symptomology, all of which justifies a longer period of hospitalization.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.