To know the changes that there has experienced the profile of patient candidate to prostatectomía radically throughout last 2 decades in our institution.

Material and methodsWe analyze retrospectively a series of 1132 patients with prostate cancer stage T1–T2, submitted to radical prostatectomy during the period 1989–2009. The series is divided into five homogeneous groups as per the number of patients and arranged chronologically. The free survival of biochemical progression (SLPB) is used as a criterion for principal forecast.

ResultsIn spite of the changes in the diagnosis and treatment of the disease, from the point of view of the forecast (SLPB) we estimate two groups different from patients: the first 250 controlled ones and the rest. The point of chronological cut is placed in this series at 1999. We find significant differences in the majority of the clinical – pathological variables as PSA's level to the diagnosis (p<0.001), percentage of palpable tumors (p<0.001), clinical stage (p<0.001), Gleason in the prostate biopsy (p=0.004), groups at risk of D’Amico (p<0.001), pathological stage (p<0.001) and percentage of patients mincingly ganglionar (p<0.001). Nevertheless, there are some undetected differences of statistical significance in the Gleason of the specimen of prostatectomy (p=0.06) and in the percentage of surgical margins (p=0.6).

ConclusionsThis study analyzes a patient-wide proceeding sample from the whole Spanish geography and presents some important information that reflects the evolution that has suffered the cancer of prostate located, so much regarding the diagnosis as to the forecast, in our country in the last 20 years.

Conocer los cambios que ha experimentado el perfil de paciente candidato a prostatectomía radical a lo largo de las últimas 2 décadas en nuestra institución.

Material y métodosAnalizamos retrospectivamente una serie de 1.132 pacientes con cáncer de próstata estadio T1-T2, sometidos a prostatectomía radical durante el periodo 1989-2009. La serie se divide en 5 grupos homogéneos en cuanto al número de pacientes y ordenados cronológicamente. Se emplea la supervivencia libre de progresión bioquímica (SLPB) como criterio pronóstico principal.

ResultadosA pesar de los cambios en el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la enfermedad, desde el punto de vista del pronóstico (SLPB) apreciamos 2 grupos diferentes de pacientes: los primeros 250 intervenidos y el resto. El punto de corte cronológico se sitúa en esta serie en 1999. Encontramos diferencias significativas en la mayoría de las variables clínico-patológicas como nivel de PSA al diagnóstico (p < 0,001), porcentaje de tumores palpables (p < 0,001), estadio clínico (p < 0,001), Gleason en la biopsia prostática (p = 0,004), grupos de riesgo de D’Amico (p < 0,001), estadio patológico (p < 0,001) y porcentaje de pacientes con afectación ganglionar (p < 0,001). No obstante, no se detectan diferencias de significación estadística en el Gleason del espécimen de prostatectomía (p = 0,06) y en el porcentaje de márgenes quirúrgicos (p = 0,6).

ConclusionesEste estudio analiza una muestra amplia de pacientes procedente de toda la geografía española y presenta algunos datos importantes que reflejan la evolución que ha sufrido el cáncer de próstata localizado, tanto en lo que respecta al diagnóstico como al pronóstico, en nuestro país en los últimos 20 años.

The discovery of the prostate specific antigen (PSA) in the 1980s made possible the early diagnosis of prostate cancer and radical prostatectomy as treatment with a curative aim, historical moment of prostate cancer treatment which we are still in. We know that the type of patient treated with surgery has evolved over the last 25 years because we have improved with the experience in diagnostic subtlety and the indications, thanks to the knowledge of clinical factors influencing the prognosis. In addition, there has been a progressive social awareness in the medical class and civil society, which have produced an increase in the number of patients diagnosed and a marked clinicopathological migration of the stages of this disease.1–4

We intend to determine the changes experienced by the profile of patient candidate to this surgery over 2 decades, and to do this we reviewed our institution's experience with 1132 patients diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer and consecutively treated with radical prostatectomy at our center.

Materials and methodsWe retrospectively analyzed the series of patients with stage T1–T2 prostate cancer surgically treated with radical prostatectomy at our center between 1989 and 2009. Before surgery, all the patients underwent detailed clinical history with physical examination and rectal examination, PSA, and prostate biopsy. Clinical staging was completed with computed tomography (CT) and from 2000 with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In patients with PSA greater than 20ng/ml or Gleason 8–10 or Gleason 7 together with PSA>10ng/ml, bone scans were performed to complete the staging.

The open approach corresponds to the technique described by Walsh5 in 1982. Until 2007, bilateral ilio-obturator lymphadenectomy was also performed and subsequently in patients with PSA>15 and/or Gleason>6. The laparoscopic approach was performed in our center for the first time in 2005. Since then, laparoscopic or open surgery has been performed according to the preferences of the surgeons and with the teaching aim that residents can learn both techniques.

After surgery, the follow-up was performed by means of PSA determinations at 3, 6, and 12 months. Later, it continued for every 6 months until a total of 3 years and, thereafter, every year. We define the PSA biochemical recurrence as a determination of PSA≥0.4ng/ml (Hybritech®) obtained at least 30 days after the surgery, and subsequently confirmed with an equal or higher value.

In order to study the evolution of the type of patient operated, we aim to discover: (a) whether there are different groups of patients; (b) how many different groups of patients were treated, and (c) where the chronological cut-off point or points are placed. To this end, the treated patients were divided into chronological sections defined by a comparable number of patients in each group, which, at the same time, represents the minimum number of patients to be treated statistically.

The main criterion chosen to assess the difference in the type of patient involved is the biochemical progression-free survival (BPFS) so that the differences in this parameter determine the definition of the groups. The clinicopathological characteristics of the resulting groups are also assessed.

To calculate qualitative variables and comparison of proportions, we used contingency tables (Chi-square test or Fisher's test), for the comparison of means in quantitative variables Student's t test, for the actuarial survival analysis the Kaplan –Meier model, and for the comparison of survival curves, the equality of survival distributions log-rank test. All the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data are presented as means±standard deviation. A p value<0.05 was required to determine the statistical significance.

ResultsIn the period 1989–2009, 1132 radical prostatectomies have been performed to patients in clinical stage T1–T2 in the Clínica Universidad de Navarra, 990 (87.5%) using open approach and 142 (12.5%) laparoscopically. The distribution by total Gleason in the piece was 611 (55.1%) Gleason 6, 276 (24.9%) Gleason 7, 222 (20%) Gleason 8–10. The pathological stage distribution was 773 (68.3%) pT2 (181 [16%] pT2a, 176 [15.5%] pT2b, 416 [36.7%] pT2c), 355 (31.3%) pT3 (228 [20.1%] pT3a, 127 [11.2%] pT3b), and 4 (0.4%) pT4. A total of 50 (4.4%) patients had positive nodal disease.

The patients were divided into 5 groups: 250 patients operated in the period 1990–1999 comprise the first group; the second consists of another 250 operated between 1999 and 2002; the third one are made of another 250 operated between 2002 and 2004; a fourth one made of another 250 operated in 2004–2007; and a fifth and final group including 132 patients whose operation was performed between 2007 and 2009. These groups are evenly distributed in numerical terms and with a clear temporary ordering that may reflect changes in the medical behavior or in the characteristics inherent to the type of patient.

When the BPFS of each group is analyzed and compared to the others, several observations become evident. On the one hand, the first group shows significant differences with each and every one of the 4 remaining groups, having a worse BPFS rate (p<0.05). Among the second, third, fourth, and fifth groups, there are no significant differences (p>0.05). Therefore, from the point of view of the prognosis in terms of biochemical progression, there are only 2 different groups (the first 250 patients treated and the rest) and the established chronological cut-off is April 1999.

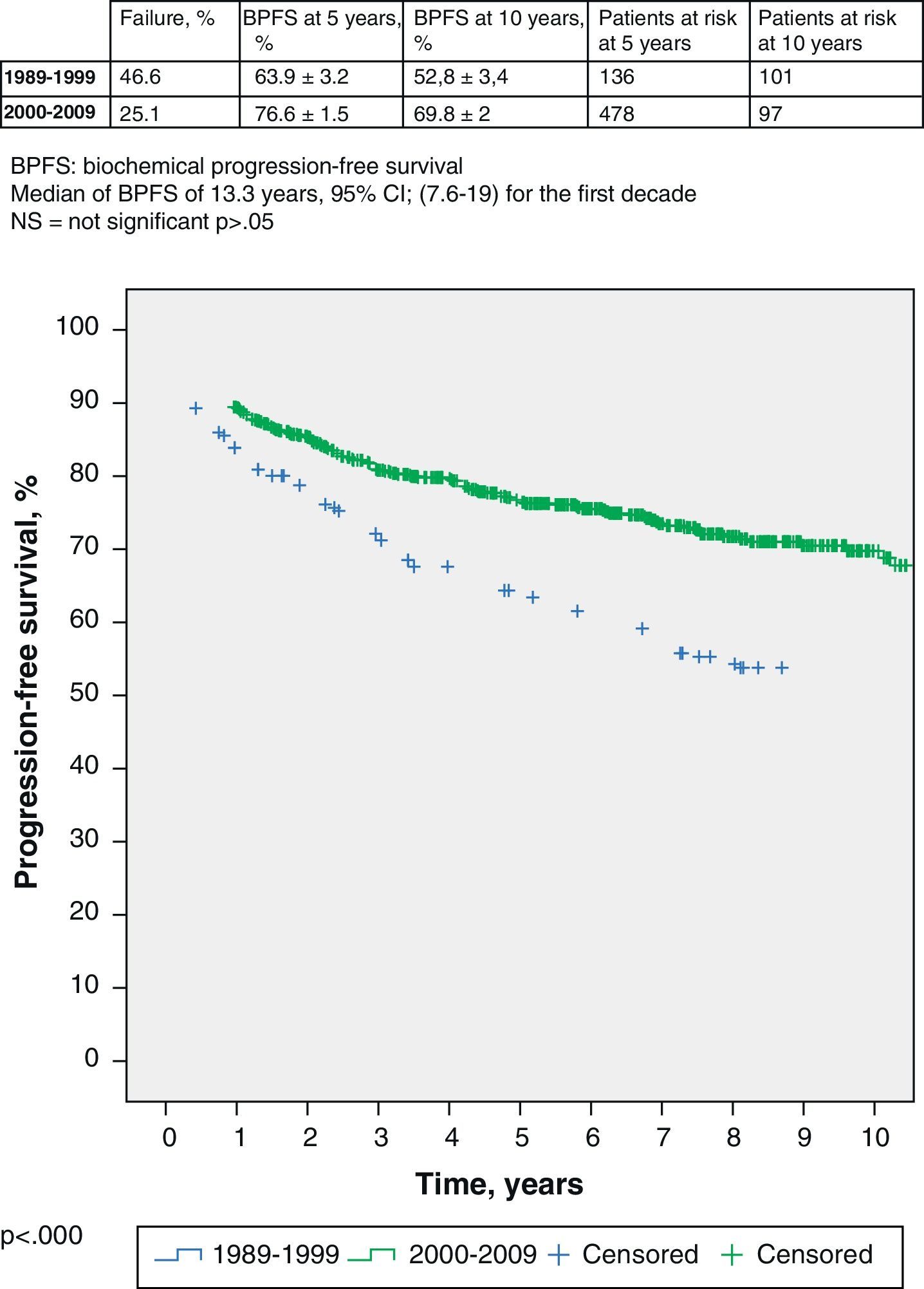

If we delve into the study of these 2 groups, we see that the median follow-up is 13 years for the former and 6.6 years for the rest. Logically, these data determine different percentage of patients with biochemical failure in each group: 46.6% in the first one and 25.1% in the second one. The BPFS of the first group (1989–1999) is 63.9% (95% CI 60.7–67.1%) at 5 years, with 136 patients at risk, and 52.8% (95% CI 49.4–56.2) at 10 years, with 101 patients at risk; respectively. The BPFS of the second group (2000–2009) at 5 years is 76.6% (95% CI 75.1–78.1%), with 478 patients at risk, and 69.8% (95% CI 67.8–71.8%) at 5 years, with 97 patients at risk (log-rank, p<0.000) (Fig. 1).

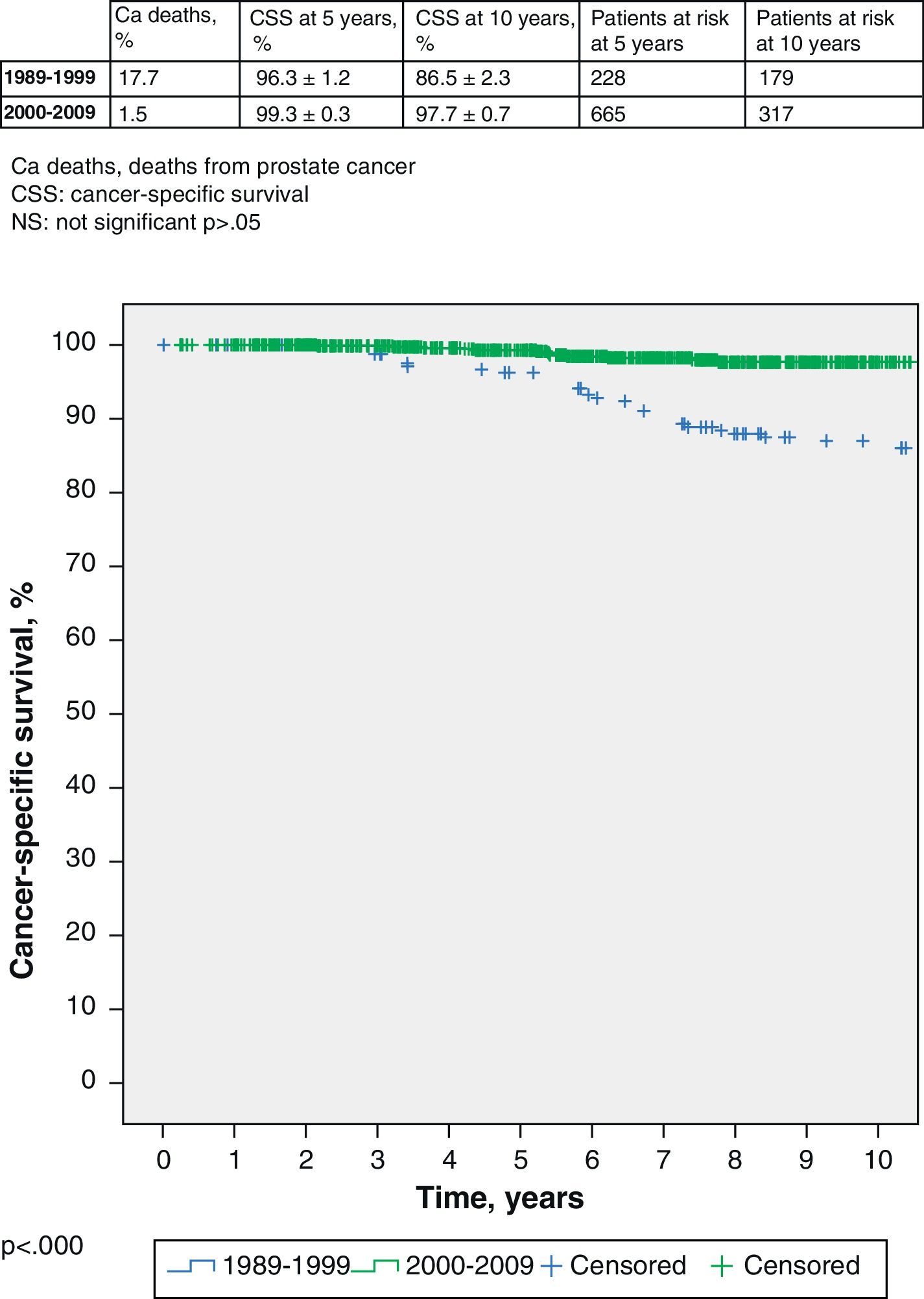

Although it is not the main aim of this work, we also find that survival is also significantly worse in the first group with 17.7% of prostate cancer deaths compared to 1.5% of deaths in the second group. The cancer-specific survival (CSS) of the first group (1989–1999) is 96.3% (95% CI 95.1–97.5%) at 5 years, with 228 patients at risk, and 86.5% (95% CI 84.2–88.8%) at 10 years, with 179 patients at risk; respectively. The CSS in the second group (2000–2009) at 5 years is 99.3% (95% CI 99.0–99.6%), with 665 patients at risk, and 97.7% (95% CI 97.0–98.4) at 10 years, with 317 patients at risk (log-rank, p<0.000) (Fig. 2).

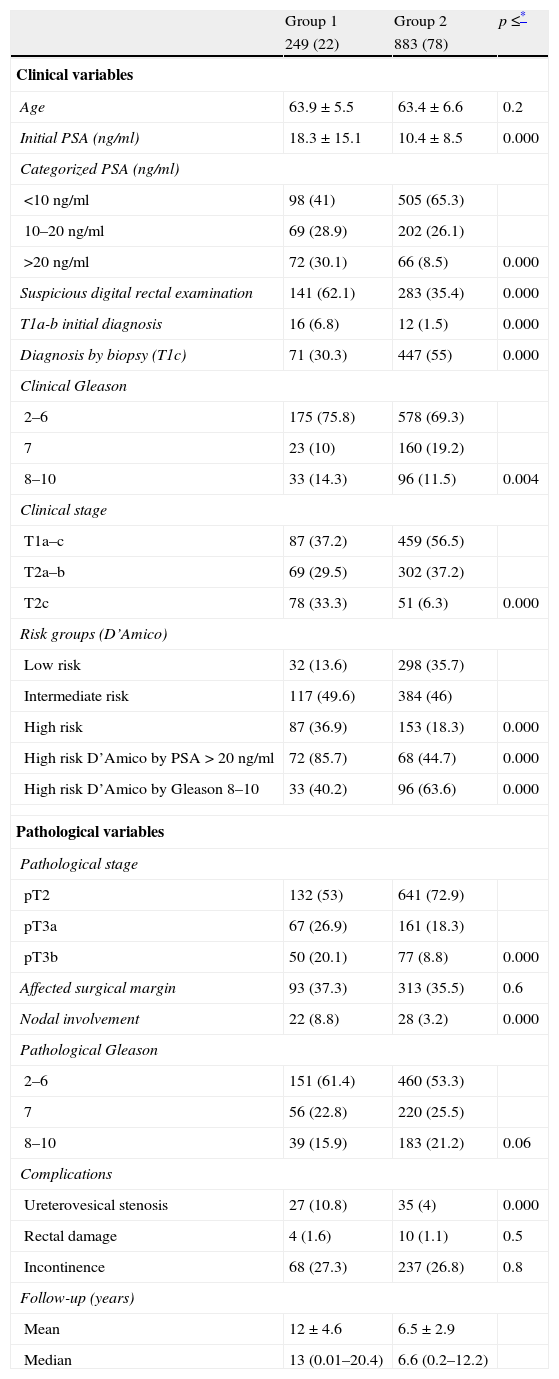

The clinicopathological characteristics of both groups are summarized in Table 1. The first one consists of patients with clinical and histopathological data justifying worse prognosis. Significant differences are shown in all the variables compared, including PSA level at diagnosis, percentage of patients with suspicious digital rectal examination, Gleason in the prostate biopsy, clinical stage, D’Amico risk groups, pathological stage, and percentage of patients with nodal involvement (Table 1). Regarding Gleason in the prostatectomy specimen, differences are detected although about to reach statistical significance (p=0.06). There are no differences between groups in the percentage of patients with impaired margins (p=0.6), possibly implying the same methodological rigor with regard to the performance of the technique over time. With regard to the complication rate, a lower rate of ureterovesical stenosis is detected in patients of the 2000–2009s than in those of the 1989–1999s, but no differences are detected regarding rectal injury or incontinence. These data are also detailed in Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of both groups (n=1132).

| Group 1 | Group 2 | p≤* | |

| 249 (22) | 883 (78) | ||

| Clinical variables | |||

| Age | 63.9±5.5 | 63.4±6.6 | 0.2 |

| Initial PSA (ng/ml) | 18.3±15.1 | 10.4±8.5 | 0.000 |

| Categorized PSA (ng/ml) | |||

| <10ng/ml | 98 (41) | 505 (65.3) | |

| 10–20ng/ml | 69 (28.9) | 202 (26.1) | |

| >20ng/ml | 72 (30.1) | 66 (8.5) | 0.000 |

| Suspicious digital rectal examination | 141 (62.1) | 283 (35.4) | 0.000 |

| T1a-b initial diagnosis | 16 (6.8) | 12 (1.5) | 0.000 |

| Diagnosis by biopsy (T1c) | 71 (30.3) | 447 (55) | 0.000 |

| Clinical Gleason | |||

| 2–6 | 175 (75.8) | 578 (69.3) | |

| 7 | 23 (10) | 160 (19.2) | |

| 8–10 | 33 (14.3) | 96 (11.5) | 0.004 |

| Clinical stage | |||

| T1a–c | 87 (37.2) | 459 (56.5) | |

| T2a–b | 69 (29.5) | 302 (37.2) | |

| T2c | 78 (33.3) | 51 (6.3) | 0.000 |

| Risk groups (D’Amico) | |||

| Low risk | 32 (13.6) | 298 (35.7) | |

| Intermediate risk | 117 (49.6) | 384 (46) | |

| High risk | 87 (36.9) | 153 (18.3) | 0.000 |

| High risk D’Amico by PSA>20ng/ml | 72 (85.7) | 68 (44.7) | 0.000 |

| High risk D’Amico by Gleason 8–10 | 33 (40.2) | 96 (63.6) | 0.000 |

| Pathological variables | |||

| Pathological stage | |||

| pT2 | 132 (53) | 641 (72.9) | |

| pT3a | 67 (26.9) | 161 (18.3) | |

| pT3b | 50 (20.1) | 77 (8.8) | 0.000 |

| Affected surgical margin | 93 (37.3) | 313 (35.5) | 0.6 |

| Nodal involvement | 22 (8.8) | 28 (3.2) | 0.000 |

| Pathological Gleason | |||

| 2–6 | 151 (61.4) | 460 (53.3) | |

| 7 | 56 (22.8) | 220 (25.5) | |

| 8–10 | 39 (15.9) | 183 (21.2) | 0.06 |

| Complications | |||

| Ureterovesical stenosis | 27 (10.8) | 35 (4) | 0.000 |

| Rectal damage | 4 (1.6) | 10 (1.1) | 0.5 |

| Incontinence | 68 (27.3) | 237 (26.8) | 0.8 |

| Follow-up (years) | |||

| Mean | 12±4.6 | 6.5±2.9 | |

| Median | 13 (0.01–20.4) | 6.6 (0.2–12.2) | |

Data presented as mean±SD or number (%) of 249 patients in group 1.

Data presented as mean±SD or number (%) of 883 patients in group 2.

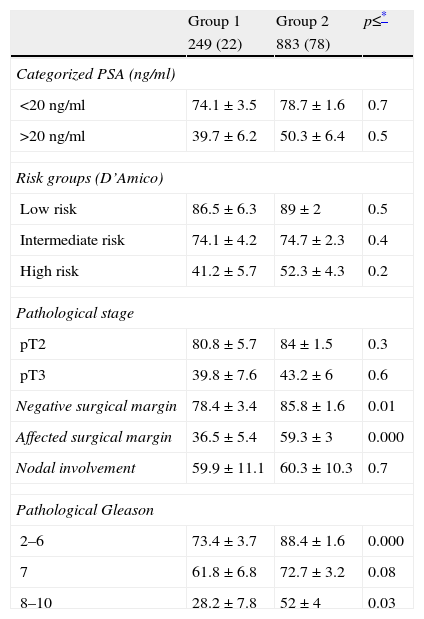

When the BPFS of both groups is compared stratifying according to different clinicopathological variables, no significant differences are detected in the BPFS over time for the different risk groups of D’Amico (low, intermediate, high) or for groups categorized according to PSA (

Biochemical progression-free survival of cohorts stratified by different variables (n=1132).

| Group 1 | Group 2 | p≤* | |

| 249 (22) | 883 (78) | ||

| Categorized PSA (ng/ml) | |||

| <20ng/ml | 74.1±3.5 | 78.7±1.6 | 0.7 |

| >20ng/ml | 39.7±6.2 | 50.3±6.4 | 0.5 |

| Risk groups (D’Amico) | |||

| Low risk | 86.5±6.3 | 89±2 | 0.5 |

| Intermediate risk | 74.1±4.2 | 74.7±2.3 | 0.4 |

| High risk | 41.2±5.7 | 52.3±4.3 | 0.2 |

| Pathological stage | |||

| pT2 | 80.8±5.7 | 84±1.5 | 0.3 |

| pT3 | 39.8±7.6 | 43.2±6 | 0.6 |

| Negative surgical margin | 78.4±3.4 | 85.8±1.6 | 0.01 |

| Affected surgical margin | 36.5±5.4 | 59.3±3 | 0.000 |

| Nodal involvement | 59.9±11.1 | 60.3±10.3 | 0.7 |

| Pathological Gleason | |||

| 2–6 | 73.4±3.7 | 88.4±1.6 | 0.000 |

| 7 | 61.8±6.8 | 72.7±3.2 | 0.08 |

| 8–10 | 28.2±7.8 | 52±4 | 0.03 |

Data presented as mean±SD or number (%) of 249 patients in group 1.

Data presented as mean±SD or number (%) of 883 patients in group 2.

The data of progression-free survival at 5 years were presented.

In recent years, there has been a significant change in the preoperative characteristics of patients with prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy. The result of this change has been the emergence of a new patient profile characterized by being younger, with localized disease, and with lower levels of PSA, which is translated in prognostic terms in better local control of the disease and better rates of progression-free and cancer-specific survival.6–11

No doubt the PSA is at the origin of these changes. Its discovery made possible the early diagnosis and the curative treatment option that represented a progressive universalization of the method, a larger number of patients diagnosed, an increase in the surgical experience, the publication of results, the improvement in diagnostic subtlety, and a clear increase in the sensitivity of society against the disease. The result has been a gradual migration to the diagnosis in earlier clinicopathological stages.6–11 The proportion of high-risk tumors has decreased significantly. In a study with 8600 patients, the low-risk proportion was 30% in 1989–1992 compared to 45% in 1999–2001. Besides, their characteristics have also changed. The determinant is no longer the PSA or the T3 DRE and now is the Gleason score.4,8–10 Simultaneously, there has been a gradual change of the Gleason grading criteria to higher stages.12

All these observations are shown in the series analyzed here. However, although over 20 years the type of patient operated has changed, only two groups are evident if we use the BPFS as segregation criterion. The dividing line confirms that it is the first 250 (those operated between 1989 and 1999) the ones who have characteristics significantly, or at the limit of statistical significance, worse in the major clinicopathological variables. This fact was also highlighted in other series.4,8–10

We have also observed a decrease in the incidental prostate cancer diagnosis (T1a, T1b), due on the one hand to the control with medical treatment of the symptoms resulting from the lower urinary tract in patients with prostate hyperplasia and the larger number of PSA determinations performed in the patients with this type of symptoms.9,13 These facts imply a proportional growth of the cases diagnosed by elevated PSA (T1c).14 Our casuistry also shows a decrease from 6.8 to 1.5% in the diagnosis of T1a and b cancer between both decades (p<0.000). A pathological migration phenomenon is shown with a tendency to pT2, consistent with the results published by other authors.6,15–21 This fact implies a clear improvement as well in the overall survival expectancy.

It is quite striking that both the pathological Gleason and the margins are not significantly different between the 2 groups in our study. We assume that it is due to the evolution of the pathological grading criteria with a trend to increase the Gleason, so that in the second period they are classified as Gleason 7 patients that in the first one would have been classified as Gleason 2–6. This phenomenon of migration of groups with prognostic significance is known as Will Rogers phenomenon,22 could explain the fact that the BPFS is significantly worse in Gleason 2–6 patients in the first group than in Gleason 2–6 patients in the second one (p<0.000). Other authors do not find differences in relation to Gleason7 either. The same is true when we study the margins, since we find no differences between the 2 groups (p=0.6). Again, the survival of patients with free margins of the first group is significantly worse than that of the same patients in the second group (p<0.000). This fact certainly implies that pathologists have refined the analysis of the piece, making it less likely that patients with affected margins are now described as negative.

We can say then that our practice reflects only 2 periods with differences in the type of patient treated with radical prostatectomy. There has not been a slow and gradual change, because in this case we would probably have found more different groups or greater heterogeneity between groups. The most reasonable explanation assumes that there was a qualitative change around 1999–2000, a period in which there was an explosion in our country in the PSA determination, both in general medicine and in business analysis, and a very significant increase in the number of patients diagnosed.8–10 In fact, to complete the first group of 250 patients operated, it took 10 years and only 5 years for the following 500, keeping then steady rate, without changes.

This study analyzes a large number of patients and has a significant medical and sociological interest because in a way it reflects how the diagnosis and treatment of localized prostate cancer has been managed in the past 20 years in an institution that treats patients from all over Spain. In this sense, these data may represent an approach to the management of this disease in our cultural environment,23 possibly different from that of the Anglo-Saxon or northern Europe countries.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Algarra R, Zudaire J, Rosell D, Robles JE, Berián JM, Pascual I. Evolución del tipo de paciente candidato a prostatectomía radical a lo largo de 2 décadas (1989–2009). Actas Urol Esp. 2013;37:347–353.