There are rather few publications about hypersensitivity reactions to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) in the paediatric age. In this study, we aimed to assess the frequency of confirmed NSAID hypersensitivity in children with a previous reported reaction to NSAID in order to investigate the role of the drug provocation test (DPT) in the diagnostic workup and to explore the factors associated with confirmed NSAID hypersensitivity.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective analysis of the clinical files from every patient under 18 years old who attended two Portuguese paediatric allergy outpatient clinics, from January 2009 to August 2014, due to a suspected NSAID hypersensitivity.

ResultsWe included 119 patients, with a median age of nine years (P25–P75: 5–14). Ibuprofen was the commonest implicated NSAID in the patients’ reports (n=94–79%). After DPT, NSAID hypersensitivity was confirmed in nine (7.6%) patients, excluded in 93 (78.2%) and was inconclusive in 17 (14.3%). In the majority (n=95–79.8%), the reaction occurred in the first 24h after intake. Eighty-four patients (70.6%) reported only cutaneous manifestations and 18 (15.1%) had systemic symptoms. Anaphylaxis represented a relative risk to NSAID hypersensitivity confirmation. No association was found for atopy and the number of previous reactions.

ConclusionIn our study, NSAID hypersensitivity was confirmed in a small proportion of the patients with a previous reported reaction. Ibuprofen was the most implicated drug with urticaria/angio-oedema as the commonest manifestation. Anaphylaxis was associated with confirmed drug hypersensitivity. The drug provocation test was essential to establish the diagnosis.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are a widely used group of medications with antipyretic and analgesic properties. This leads to frequent reports of hypersensitivity reactions to NSAIDs (NSAID-H) by adults as well as children. The reported prevalence of hypersensitivity reactions to NSAIDs in the general population is 0.3% in adults, with similar results in children.1 In Portugal, the prevalence of self-reported NSAID-H was 0.5% among children attending day-care centres.2

A previous study, which was performed in Portugal among children, showed that, although adverse drug reactions are frequently described in this population, after a thorough investigation, a true drug hypersensitivity will be confirmed in only a few cases.3

In patients evaluated due to a possible NSAID-H, the investigation confirmed this suspicion in a minority of them.4,5 The drug provocation test (DPT) with the culprit drug is considered the gold standard to diagnose NSAID hypersensitivity.6,7 The prevalence of immunologically mediated reactions to NSAIDs ranges from 0.1% to 3.6%.8

There are rather few studies in the paediatric population regarding NSAID hypersensitivity reactions. Atopy, immediate-type reactions or respiratory symptoms as previous manifestations have been identified as risk factors by some authors.5

The aim of our study was to assess the frequency of confirmed NSAID hypersensitivity in children with a previous reported reaction to NSAID, to investigate the role of the drug provocation test (DPT) in the diagnostic workup and to explore the factors associated with confirmed NSAID hypersensitivity.

MethodsStudy design, setting and participantsWe conducted a retrospective analysis of the clinical files from every patient under 18 years old who attended two Portuguese Immunoallergy Departments (one in Lisbon and another in Oporto), from January 2009 to August 2014, due to a suspected NSAID hypersensitivity.

The participating centres were the Immunoallergy Department of Dona Estefânia Hospital, CHLC, in Lisbon and the Immunoallergy Department of Maria Pia Hospital, CHP, in Oporto, which are the two main public paediatric allergy centres in Portugal.

Data collectionData was retrospectively collected by a standardised questionnaire in order to gather information about NSAID reactions and diagnostic test results. In both allergy centres, the usual diagnostic workup includes a first clinical assessment of the reported reaction followed by a DPT.

The standardised questionnaire comprised questions regarding the chronology of the reaction (acute – if the reaction occurred in the first 24h after the intake; delayed – if it occurred after 24h),7,8 implicated drugs, clinical presentation, number of previous reactions, age at the time of the first reaction, drug provocation test result, atopic status (defined as at least one positive skin prick test – SPT – to aero/food allergens) and previous diagnosis of allergic diseases (asthma, atopic eczema, allergic rhinitis, food allergy and chronic urticaria). Anaphylaxis was defined as a severe, life-threatening generalised or systemic hypersensitivity reaction, according to the literature.9

Drug provocation testIf there was no contraindication,7,8,10 NSAID provocation test was performed to confirm or exclude the presence of hypersensitivity and to classify the reaction.

Open DPTs were conducted by an experienced allergist according to the recommendations of the ENDA (European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology Drug Hypersensitivity Interest Group).10 The diagnostic work-up included single-blind, placebo-controlled DPT if the reported symptoms were subjective or if the open DPT performed ended in an unclear result. Incremental doses of the drug were administrated at intervals of 30–60min, stopping as soon as the first objective symptoms occurred or at the end of the intake of the defined doses of the protocol. The first administration was usually 1/10 of the therapeutic dose, according to the weight and age, and the total cumulative dose was similar to the usual maximal individual intake dose (adjusted to weight and age). Symptoms and vital signs were monitored before, during and at the end of the DPT. Three hours was the minimal period of surveillance after the last drug administration. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians before the procedure.

The DPT was considered positive if it reproduced the previous reported reaction or elicited objective manifestations.

A NSAID-H confirmation was assumed when the patient had a positive DPT with the implicated or alternative NSAID. A NSAID-H was excluded if the DPT with the implicated drug was negative. The investigation was considered inconclusive when DPT was negative with the alternative NSAID but a DPT with the culprit NSAID was not performed (in this case, a single NSAID-H cannot be excluded), or when a DPT was not performed at all (due to the parent's refusal).

Statistical analysisAn exploratory analysis of the variables of interest (gender, age, presence of atopy and allergic conditions, type of drug, manifestations and chronology, NSAID tolerance) was carried out. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparisons of differences between medians. A chi-squared test or Fisher Exact Test was used to compare the categorical variables. The level of significance considered was α=0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23® (New York, USA).

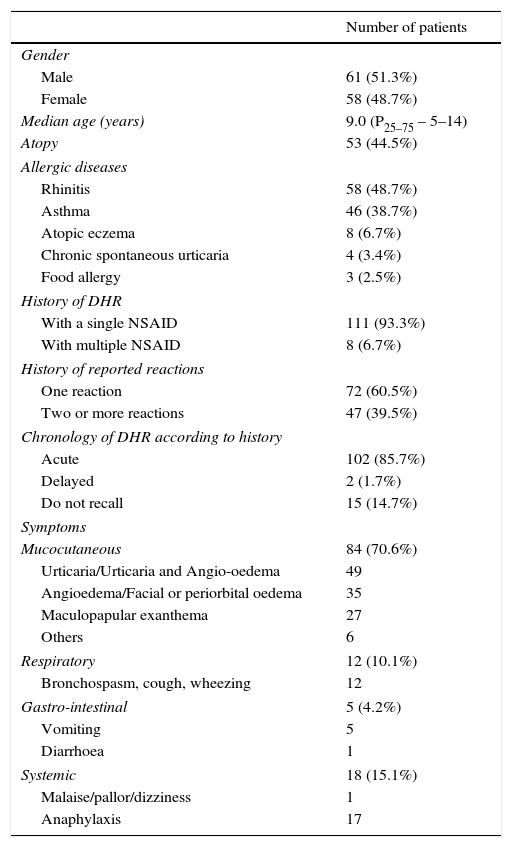

ResultsWe included 119 children, 51.3% boys, with a median age of 9.0 years (P25–75 – 5–14). Atopy was present in 53 (44.5%) and 60.5% had a previous diagnosis of allergic diseases. According to the clinical reports, 111 patients (93.3%) described a reaction to a single NSAID (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of patients and clinical manifestations of the reported reaction.

| Number of patients | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 61 (51.3%) |

| Female | 58 (48.7%) |

| Median age (years) | 9.0 (P25–75 – 5–14) |

| Atopy | 53 (44.5%) |

| Allergic diseases | |

| Rhinitis | 58 (48.7%) |

| Asthma | 46 (38.7%) |

| Atopic eczema | 8 (6.7%) |

| Chronic spontaneous urticaria | 4 (3.4%) |

| Food allergy | 3 (2.5%) |

| History of DHR | |

| With a single NSAID | 111 (93.3%) |

| With multiple NSAID | 8 (6.7%) |

| History of reported reactions | |

| One reaction | 72 (60.5%) |

| Two or more reactions | 47 (39.5%) |

| Chronology of DHR according to history | |

| Acute | 102 (85.7%) |

| Delayed | 2 (1.7%) |

| Do not recall | 15 (14.7%) |

| Symptoms | |

| Mucocutaneous | 84 (70.6%) |

| Urticaria/Urticaria and Angio-oedema | 49 |

| Angioedema/Facial or periorbital oedema | 35 |

| Maculopapular exanthema | 27 |

| Others | 6 |

| Respiratory | 12 (10.1%) |

| Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing | 12 |

| Gastro-intestinal | 5 (4.2%) |

| Vomiting | 5 |

| Diarrhoea | 1 |

| Systemic | 18 (15.1%) |

| Malaise/pallor/dizziness | 1 |

| Anaphylaxis | 17 |

DHR – drug hypersensitivity reaction; NSAID – non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Prior to the investigation, 70 (58.8%) patients had proven tolerability to at least one alternative NSAID (which was verified after the reported reaction – the patient took an alternative NSAID after the reported reaction but previous to this investigation): 60 (85.7%) referred tolerance to paracetamol, eight (11.4%) to acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), three (4.3%) to metamizole, two (2.9%) to ibuprofen and one (1.4%) to nimesulide.

In our sample, 47 (39.5%) patients reported two or more previous reactions (41 with the same drug and six with different NSAID) (Table 1).

Parents reported a previous adverse reaction to other drug class in 24 (20%) of the children, mostly to antibiotics (n=17).

At the time of the first reported reaction, 84 (70.6%) patients had only mucocutaneous manifestations after the intake of the implicated NSAID, 18 (15.1%) had systemic symptoms (17 anaphylaxis), 12 (10.1%) had isolated respiratory manifestations and five (4.2%) referred gastrointestinal symptoms (Table 1).

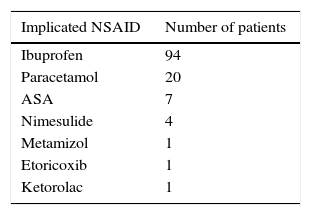

The most common implicated NSAID in the patients’ reaction reports was ibuprofen (N=94; 79%) (Table 2).

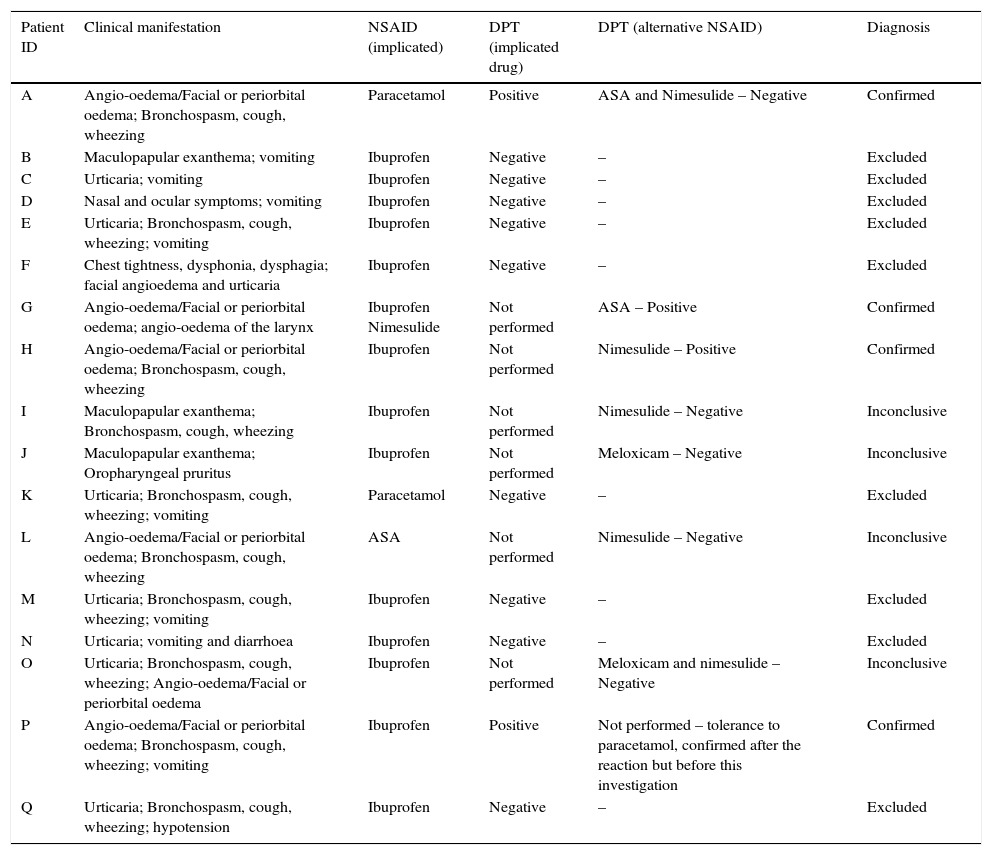

The characteristics of the first reaction and the results of the investigation performed in the patients who reported anaphylaxis are detailed in Table 3.

Clinical manifestations of the reported reaction, implicated drug and drug provocation tests results in the anaphylaxis cases.

| Patient ID | Clinical manifestation | NSAID (implicated) | DPT (implicated drug) | DPT (alternative NSAID) | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Angio-oedema/Facial or periorbital oedema; Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing | Paracetamol | Positive | ASA and Nimesulide – Negative | Confirmed |

| B | Maculopapular exanthema; vomiting | Ibuprofen | Negative | – | Excluded |

| C | Urticaria; vomiting | Ibuprofen | Negative | – | Excluded |

| D | Nasal and ocular symptoms; vomiting | Ibuprofen | Negative | – | Excluded |

| E | Urticaria; Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing; vomiting | Ibuprofen | Negative | – | Excluded |

| F | Chest tightness, dysphonia, dysphagia; facial angioedema and urticaria | Ibuprofen | Negative | – | Excluded |

| G | Angio-oedema/Facial or periorbital oedema; angio-oedema of the larynx | Ibuprofen Nimesulide | Not performed | ASA – Positive | Confirmed |

| H | Angio-oedema/Facial or periorbital oedema; Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing | Ibuprofen | Not performed | Nimesulide – Positive | Confirmed |

| I | Maculopapular exanthema; Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing | Ibuprofen | Not performed | Nimesulide – Negative | Inconclusive |

| J | Maculopapular exanthema; Oropharyngeal pruritus | Ibuprofen | Not performed | Meloxicam – Negative | Inconclusive |

| K | Urticaria; Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing; vomiting | Paracetamol | Negative | – | Excluded |

| L | Angio-oedema/Facial or periorbital oedema; Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing | ASA | Not performed | Nimesulide – Negative | Inconclusive |

| M | Urticaria; Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing; vomiting | Ibuprofen | Negative | – | Excluded |

| N | Urticaria; vomiting and diarrhoea | Ibuprofen | Negative | – | Excluded |

| O | Urticaria; Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing; Angio-oedema/Facial or periorbital oedema | Ibuprofen | Not performed | Meloxicam and nimesulide – Negative | Inconclusive |

| P | Angio-oedema/Facial or periorbital oedema; Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing; vomiting | Ibuprofen | Positive | Not performed – tolerance to paracetamol, confirmed after the reaction but before this investigation | Confirmed |

| Q | Urticaria; Bronchospasm, cough, wheezing; hypotension | Ibuprofen | Negative | – | Excluded |

NSAID – non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; ASA – acetylsalicylic acid; DPT – drug provocation test.

Total cumulative doses were: ibuprofen 10mg/kg until 600mg, paracetamol 15mg/kg until 1000mg, nimesulide 100mg and ASA 20mg/kg until 1000mg.

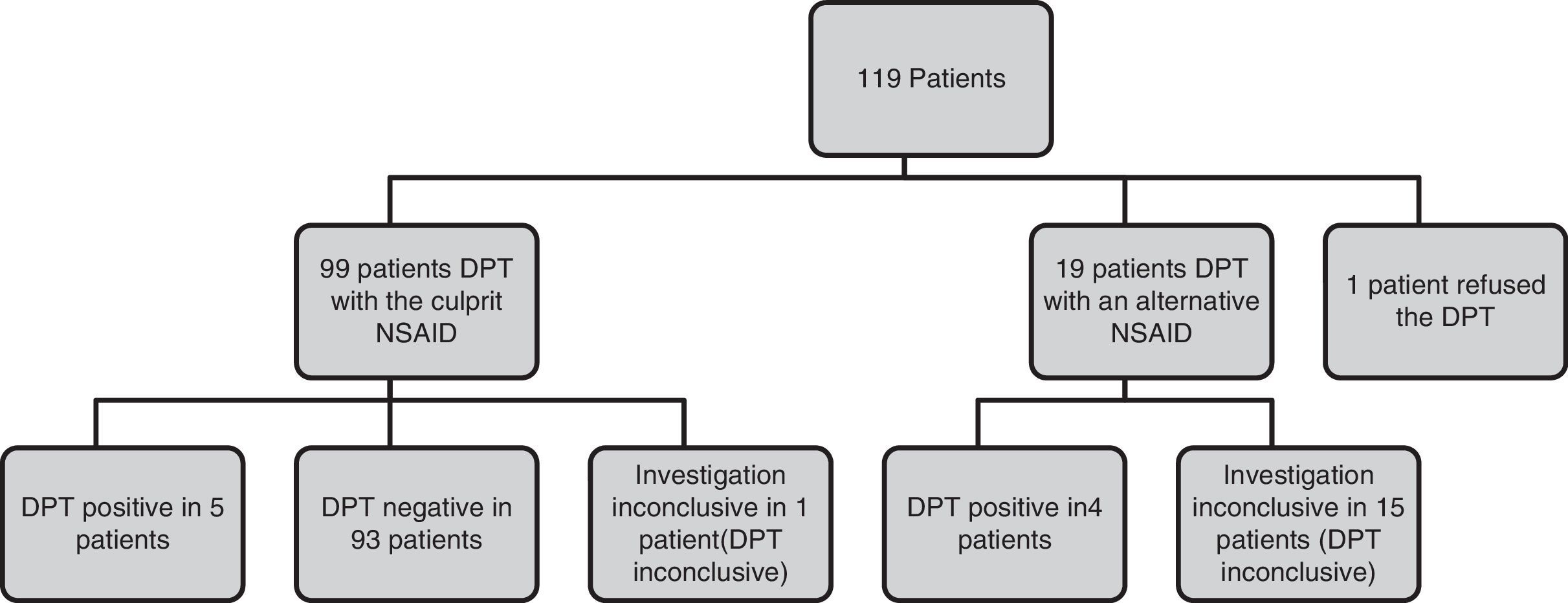

The DPT diagram is presented in Fig. 1. In our sample, 99 (83.2%) patients were challenged with the implicated NSAID (positive in five DPT) and 19 (16%) with an alternative NSAID due to severity of the reactions/patient refusal (positive in four). One patient refused the DPT with the implicated drug as he already had a known tolerance to an alternative NSAID.

The presence of NSAID hypersensitivity was confirmed in nine patients (7.6%) (Table 4), excluded in 93 (78.2%) and inconclusive in 17 (14.3%) patients.

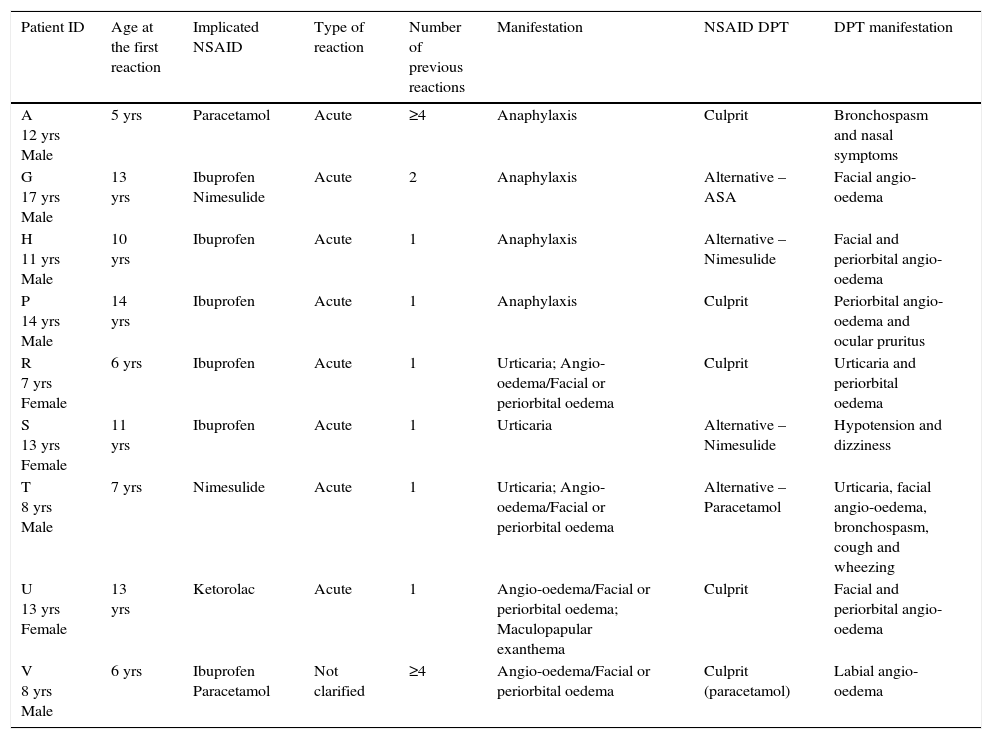

Characterisation of the patients with confirmed NSAID-H.

| Patient ID | Age at the first reaction | Implicated NSAID | Type of reaction | Number of previous reactions | Manifestation | NSAID DPT | DPT manifestation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A 12 yrs Male | 5 yrs | Paracetamol | Acute | ≥4 | Anaphylaxis | Culprit | Bronchospasm and nasal symptoms |

| G 17 yrs Male | 13 yrs | Ibuprofen Nimesulide | Acute | 2 | Anaphylaxis | Alternative – ASA | Facial angio-oedema |

| H 11 yrs Male | 10 yrs | Ibuprofen | Acute | 1 | Anaphylaxis | Alternative – Nimesulide | Facial and periorbital angio-oedema |

| P 14 yrs Male | 14 yrs | Ibuprofen | Acute | 1 | Anaphylaxis | Culprit | Periorbital angio-oedema and ocular pruritus |

| R 7 yrs Female | 6 yrs | Ibuprofen | Acute | 1 | Urticaria; Angio-oedema/Facial or periorbital oedema | Culprit | Urticaria and periorbital oedema |

| S 13 yrs Female | 11 yrs | Ibuprofen | Acute | 1 | Urticaria | Alternative – Nimesulide | Hypotension and dizziness |

| T 8 yrs Male | 7 yrs | Nimesulide | Acute | 1 | Urticaria; Angio-oedema/Facial or periorbital oedema | Alternative – Paracetamol | Urticaria, facial angio-oedema, bronchospasm, cough and wheezing |

| U 13 yrs Female | 13 yrs | Ketorolac | Acute | 1 | Angio-oedema/Facial or periorbital oedema; Maculopapular exanthema | Culprit | Facial and periorbital angio-oedema |

| V 8 yrs Male | 6 yrs | Ibuprofen Paracetamol | Not clarified | ≥4 | Angio-oedema/Facial or periorbital oedema | Culprit (paracetamol) | Labial angio-oedema |

Yrs – years; NSAID – non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; DPT – drug provocation test.

Of the nine patients with proven NSAID-H, seven had a previous diagnosis of an allergic disease (five atopic, sensitised to house dust mites). Of the 93 patients without NSAID-H, 30 had confirmed sensitisation to house dust mites.

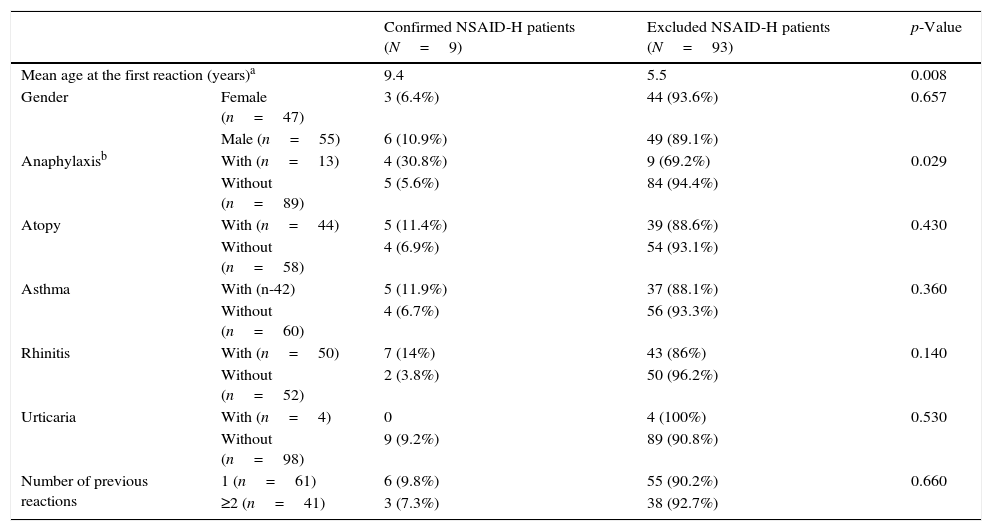

Patients with confirmed hypersensitivity were older at the time of the first reaction (p=0.008) than patients in which NSAID-H was excluded. A reported history of anaphylaxis was associated with confirmed NSAID-H (p=0.029) (RR=5.48, 95% CI 1.69–17.8, p=0.0047). No statistically significant differences were found for asthma, urticaria, atopy and a number of previous reactions. However, patients with asthma or rhinitis presented a higher frequency of confirmed NSAID-H (11.9% versus 6.7% for asthma and 14% versus 3.8% for rhinitis) than those without allergic respiratory disease (Table 5).

Characterisation of the patients that had confirmed and excluded NSAID-H.

| Confirmed NSAID-H patients (N=9) | Excluded NSAID-H patients (N=93) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at the first reaction (years)a | 9.4 | 5.5 | 0.008 | |

| Gender | Female (n=47) | 3 (6.4%) | 44 (93.6%) | 0.657 |

| Male (n=55) | 6 (10.9%) | 49 (89.1%) | ||

| Anaphylaxisb | With (n=13) | 4 (30.8%) | 9 (69.2%) | 0.029 |

| Without (n=89) | 5 (5.6%) | 84 (94.4%) | ||

| Atopy | With (n=44) | 5 (11.4%) | 39 (88.6%) | 0.430 |

| Without (n=58) | 4 (6.9%) | 54 (93.1%) | ||

| Asthma | With (n-42) | 5 (11.9%) | 37 (88.1%) | 0.360 |

| Without (n=60) | 4 (6.7%) | 56 (93.3%) | ||

| Rhinitis | With (n=50) | 7 (14%) | 43 (86%) | 0.140 |

| Without (n=52) | 2 (3.8%) | 50 (96.2%) | ||

| Urticaria | With (n=4) | 0 | 4 (100%) | 0.530 |

| Without (n=98) | 9 (9.2%) | 89 (90.8%) | ||

| Number of previous reactions | 1 (n=61) | 6 (9.8%) | 55 (90.2%) | 0.660 |

| ≥2 (n=41) | 3 (7.3%) | 38 (92.7%) | ||

In the present study, we found a 7.6% frequency of NSAID-H. Ibuprofen was the most frequent implicated drug and urticaria and angio-oedema were the commonest clinical manifestations.

Children often have a history of NSAID reactions, particularly to ibuprofen. According to the literature, in 86% of the single reactors and in 56% of cross-reactors, a NSAID-H is not confirmed.6 It is believed that concomitant conditions such as infections, fever, or the use of other drugs might play a role in the pathophysiology of the reaction, eliciting symptoms in these patients.6,8

A well-documented clinical history is essential for the correct diagnosis of NSAID-H and should include a description of the symptoms, time interval between drug administration and the symptoms onset, implicated drugs, drugs tolerated after the reaction, route of administration, number of episodes and underlying diseases.8 However, a diagnosis of NSAID-H supported solely by the clinical history may lead to overdiagnosis.4

A history of repeated previous reactions was reported to predict a future response to NSAID.7 In our study, similarly to the study by Yilmaz et al.6 the number of previous reactions was not associated with a positive DPT result.

It was suggested that ibuprofen could be used to detect the cross-reactive type of NSAID-H in children.6 According to our results, ibuprofen was the most frequent reported culprit in suspected reactions and the commonest drug involved in challenge-proven NSAID-H. This is in line with Zambonino et al.1 and Guvenir et al.4 This is partially explained because in the paediatric age the prescription of NSAIDs is largely restricted to a few drugs, namely ibuprofen and paracetamol.

During the investigation of a suspected NSAID-H, it is important to check for paracetamol tolerance in all children with cross-intolerance to NSAIDs because there are few medications approved for the treatment of fever or inflammation at younger ages.1 It has been shown that reactivity to paracetamol among NSAID-H patients ranges from 0% to 25%.8,11 In the present study, 2 out of 9 patients (22%) with confirmed NSAID-H reacted to paracetamol.

In this work, as found by other authors,1,12,13 urticaria and angio-oedema were the most frequent manifestations reported by the patients, with facial angio-oedema, with or without generalised urticaria, as the most common clinical presentation.8,11 In the majority of the patients with cutaneous manifestations (94.0%), NSAID-H was confirmed in only five patients. The low frequency of confirmed diagnosis has been reported by other authors, suggesting that even in patients with a history of urticaria/angio-oedema, the diagnostic procedure could safely start with the offending NSAID.14

Anaphylaxis is usually considered a contraindication for DPT because of the risk associated. In the work of Zambonino et al.1 the DPT with the culprit drug was not performed in patients who reported anaphylaxis. However, in the study of Yilmaz et al.6 a report of anaphylaxis was not associated with the DPT result. In our work, 17 patients reported anaphylaxis as the clinical manifestation. However, the hypersensitivity was only confirmed in four. These DPT were performed in the majority of anaphylaxis reported cases, as other possible causes, such as viral infections or other drugs, could not be ruled out. Most drug challenges were negative, although this clinical presentation was associated with more positive results than have been described in the literature.7

In what concerns atopy, several studies have shown an association between NSAID-H, allergic diseases (asthma, rhinitis) and atopy sensitisation in children and adults, which has been considered a significant risk factor for NSAID-H in young children.1,11,15–17 An association particularly with house dust mite sensitisation has been described.18 The exact mechanism remains unclear.15,17 However, this association was not found by other authors.4,14

In our study, patients with confirmed NSAID-H presented a higher frequency of asthma and rhinitis than patients with excluded NSAID-H. Almost half (44.5%) of our patients were atopic. Nevertheless, these differences were not statistically significant possibly due to the low number of positive patients.

In our sample, genders were equally distributed (58 girls and 61 boys). However, in the nine patients with NSAID-H, six were male. These data are consistent with previous reports.11 The male preponderance may be explained considering the association of NSAID-H with atopy and the somewhat increased prevalence of atopic diseases in boys.11

Regarding the median age at the time of the first reaction, patients with confirmed NSAID-H were older than those for which the diagnosis was excluded. This difference, which was previously described,19 could be related to the fact that younger children are more susceptible to viral infections, causing skin eruptions and leading to a deceptive diagnosis of NSAID-H.

DPT is the gold standard for the NSAID-H diagnosis,7,8,10 and a negative result should be reassuring to the patient. Nonetheless, patients frequently continue to avoid the tested NSAID after a negative result,20 emphasising the importance of an effective communication between patients and physicians. There are few published studies about NSAID-H in children. For this reason, we consider that the present study provides additional information about this topic, reinforcing the need to undergo an investigation by a DPT with the implicated NSAID.

ConclusionWe found a low frequency (7.6%) of true NSAID-H in children with a previous NSAID reaction. Ibuprofen was the most frequently implicated drug and urticaria and angio-oedema were the commonest clinical manifestation. Anaphylaxis was a relative risk to confirmed drug hypersensitivity. Despite this, in the face of reported anaphylaxis, the clinical history might not be sufficient to establish a final diagnosis of NSAID-H. The drug provocation test proved to be essential in the NSAID-H diagnosis workup and should be considered, even when systemic symptoms are reported.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.