Autoimmune mechanisms play a role in the pathophysiology of chronic urticaria. As the genetic background of autoimmunity is well proven, the role of genetics in chronic urticaria is hypothesised.

Methods153 unrelated chronic spontaneous urticaria patients with a positive result of autologous serum skin test were included into the study, as were 115 healthy volunteers as control group. In all subjects we analysed CCR2 G190A and CCR5 d32 polymorphisms.

ResultsWe noticed higher prevalence of CCR2 A allele as well as lower frequency of CCR5 d32 in chronic urticaria group in comparison to control group, with borderline statistical significance. Additionally, we assumed haplotype Gd statistically significant negative chronic urticaria association with tendency to higher frequency of Aw haplotype in this group.

ConclusionsThe results of our study imply the role of autoimmune components in chronic urticaria pathogenesis and present chronic urticaria as possibly genetically related disorder.

Chronic urticaria (CU) is a relatively common dermatosis characterised by the manifestation of wheals and/or angio-oedema for at least six weeks. In the pathophysiology of CU inflammatory, hormonal as well as autoimmune abnormalities should be taken into account.1–3 The last one can be connected with IgG anti-IgE antibodies or antibodies directed against the high-affinity IgE receptor (Fc¿R1).4 Additionally, this form of CU is frequently associated with other autoimmune diseases. Since the genetic background of autoimmune disorders is widely proven, the role of genetics in some forms of CU is hypothesised.5

Chemokine receptors polymorphisms play a significant role in some autoimmune mechanisms. Chemotactic responses are mediated by receptors being members of seven-transmembrane-domain proteins signalling through heterotrimeric guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-binding proteins.6

The possible inflammatory cause of CU is widely discussed.7 The role of chemokine receptors in inflammation is connected with enabling cells to migrate in response to proper signalling.8 As a result, subjects with different receptor expressions might present a different mode of initiation of inflammatory and autoimmune processes.

The CCR2 gene produces two isoforms, i.e. CCR2A and CCR2B. CCR2-64I variant is an effect of single nucleotide change in the CCR2 gene leading to the substitution of the amino acid valine (V) with isoleucine (I) in the first transmembrane domain of the receptor. CCR2-64I product increases the stability of CCR2A and plays a role in the development of Th2-type response. CCR2-64I allele is more common in asthmatic (especially atopic) patients.9,10 Additionally, this variant was proven to be associated with type 1 diabetes (T1D), being protective against the development of sarcoidosis.11,12

CCR5 activates multiple intracellular processes and plays an important role in T cell functions.13,14 CCR5 receptor genes are supposed to be involved in autoimmunity as well. 32 base pair (bp) deletion in the CCR5 gene (CCR5 d32) results in premature termination in the region coding the extracellular loop of the CCR5 receptor. It results in non-functional receptor resistant to specific chemokines as well as in decreased susceptibility to HIV-1 infection.15 There are numerous studies suggesting an influence of CCR5 d32 on rheumatoid arthritis (RA).16–20

In our study we decided to evaluate whether CCR2 and CCR5 polymorphisms influence the susceptibility to CU in the Polish population.

Materials and methodsStudy sample characteristicsWe included 153 unrelated chronic spontaneous urticaria patients (113 females and 40 males, mean age 38.2, with range 20–61 years) with a positive result of autologous serum skin test (ASST). We established the diagnosis of chronic spontaneous urticaria on the precise medical history and physical examination. Additionally we examined 115 unrelated healthy volunteers (83 females and 32 males, mean age 43.5 with range 19–59) in control group.

DNA isolation and genotyping of polymorphismsGenomic DNA was obtained from leukocytes with usage of MasterPure™ DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI, USA).

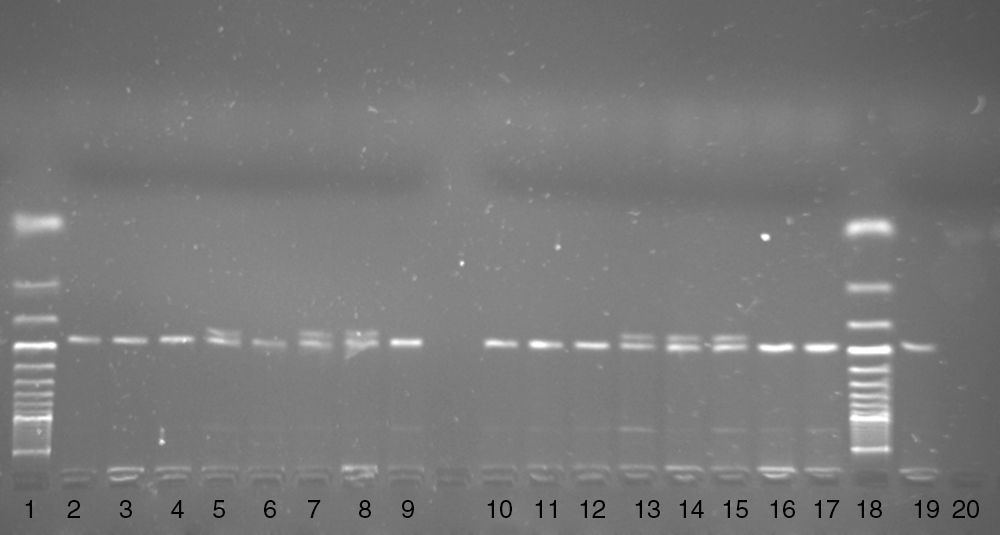

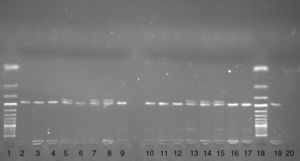

Two polymorphisms i.e. the G190A polymorphism (rs1799864, V64I) in the CCR2 gene and the d32 polymorphism in the CCR5 gene, were genotyped. The G190A polymorphism in the CCR2 gene was genotyped using the PCR-FFLP method. The DNA fragment was amplified using the following primers F 5′-TTG TGG GCA ACA TGA TGG and R 5′-CTG TGA ATA ATT TGC ACA TTG.21 In the F primer cytosine was replaced by adenine (underlined) to create a digestion sited for the BseJI restriction enzyme in the presence of the A allele. The 182bp PCR product was digested with the BseJI restriction enzyme (Fermentas, Latvia) for 180min at 65°C. After digestion, the PCR product was electrophoresed on 3.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide. In the presence of the A allele a 164bp DNA fragment and in the presence of G allele a 182bp PCR product were observed on agarose gel (Fig. 1).

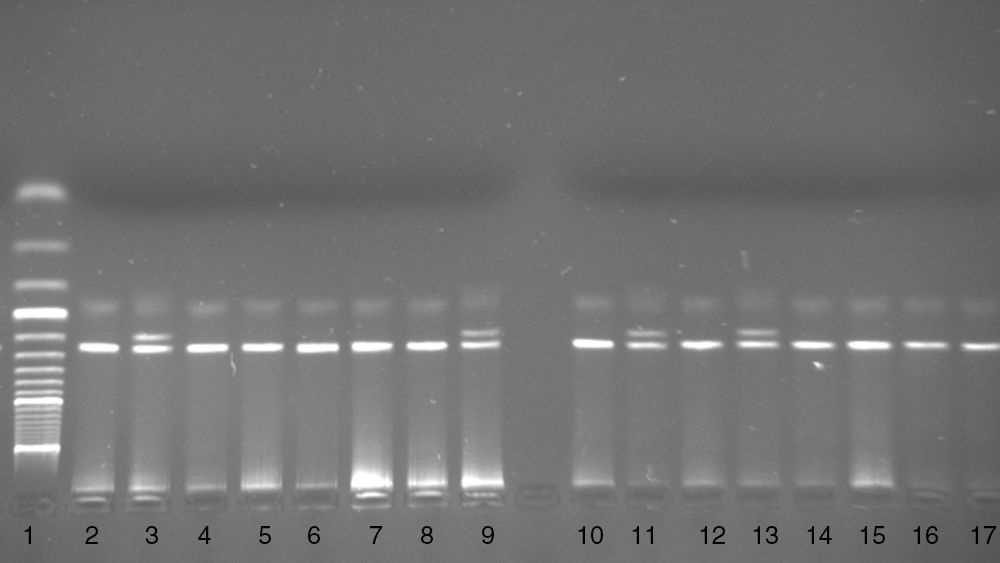

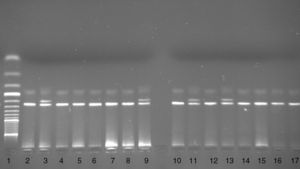

The d32 polymorphism in the CCR5 gene was genotyped using the PCR based method. A DNA fragment was amplified using the following primers: P1 5′-TTT ACC AGA TCT CAA AAA GAA G-3′ and P2 5′-GGA GAA GGA CAA TGT TGT AGG-3′.22 The PCR product was electrophoresed on 3.0% agarose gel with ethidium bromide. In the presence of the wild type (wt) allele a 274bp PCR product and in the presence of the deletion allele a 242bp PCR product were seen on agarose gel (Fig. 2).

Statistical analysisAllele and genotype frequency calculations were performed with Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates’ continuity correction. Additionally odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were analysed. Uncertain haplotype frequencies calculation was performed with the Package ‘BayHap’ (R version 2.7.0 from The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://cran.r-project.org).

The project was approved by Ethical Committee of the Medical University of Silesia.

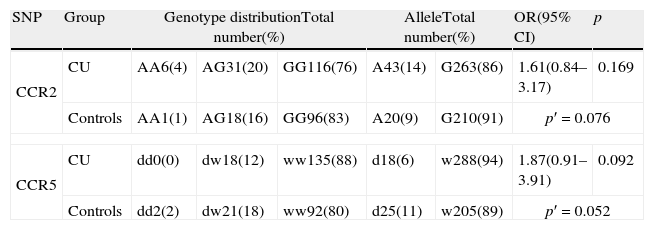

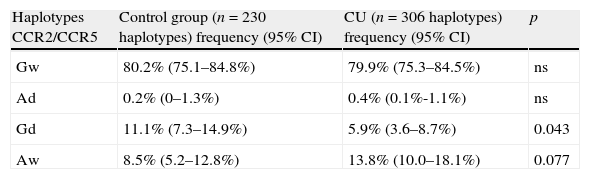

ResultsStatistical analysis for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium revealed no deviation either in the CU group or in the control group. The data obtained for the analysed polymorphisms are presented in Table 1. We noticed close to statistical significance higher prevalence of rs1799864 A allele among CU patients when compared to the controls. A allele prevalence was 1.7-fold higher in the CU group. Additionally, we found lower frequency of d32 in the CU group in comparison to the control group, with borderline statistical significance. The analysed polymorphisms were in linkage disequilibrium (D′=0.73). After haplotype construction analysis there was a negative relationship between Gd and CU with tendency to higher frequency of Aw haplotype in this group (Table 2).

CCR2 and CCR5 genotype and allele distribution in chronic urticaria patients and healthy controls.

| SNP | Group | Genotype distributionTotal number(%) | AlleleTotal number(%) | OR(95% CI) | p | |||

| CCR2 | CU | AA6(4) | AG31(20) | GG116(76) | A43(14) | G263(86) | 1.61(0.84–3.17) | 0.169 |

| Controls | AA1(1) | AG18(16) | GG96(83) | A20(9) | G210(91) | p′=0.076 | ||

| CCR5 | CU | dd0(0) | dw18(12) | ww135(88) | d18(6) | w288(94) | 1.87(0.91–3.91) | 0.092 |

| Controls | dd2(2) | dw21(18) | ww92(80) | d25(11) | w205(89) | p′=0.052 | ||

CU, chronic urticaria; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; p, statistical significance (p′=allele frequency statistical significance). The odds ratio was calculated for patients homozygous or heterozygous carrying risk allele vs. homozygous.

CCR2 and CCR5 haplotype distribution in chronic urticaria patients and healthy controls.

| Haplotypes CCR2/CCR5 | Control group (n=230 haplotypes) frequency (95% CI) | CU (n=306 haplotypes) frequency (95% CI) | p |

| Gw | 80.2% (75.1–84.8%) | 79.9% (75.3–84.5%) | ns |

| Ad | 0.2% (0–1.3%) | 0.4% (0.1%-1.1%) | ns |

| Gd | 11.1% (7.3–14.9%) | 5.9% (3.6–8.7%) | 0.043 |

| Aw | 8.5% (5.2–12.8%) | 13.8% (10.0–18.1%) | 0.077 |

CU, chronic urticaria; CI, confidence interval; p, statistical significance; ns, statistically non-significant.

Up- or down-regulation of chemokine and chemokine receptor expression has been observed in a broad range of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases and is thought to affect disease susceptibility, progression as well as its severity.

The pathogenesis of RA is closely related to functional variants such as CCR5 d32. Chemokine receptors are essential in cell trafficking to synovium.17–19 Activated T lymphocytes with Th1 phenotype express CCR5 receptors.13,14 These lymphocytes were proven to be present in the synovial membrane and fluid of RA patients.23,24 Gomez-Reino et al.18 demonstrated negative relation between the CCR5 gene homozygous d32 deletion and RA, although individuals carrying the homozygous d32 deletion and severe RA or juvenile chronic arthritis were reported.20 The recent study provides further evidence for a protective effect of the CCR5 d32 variant on RA in a New Zealand cohort.22 In Slovak Caucasians, carrier status for the CCR5 d32 allele may also contribute to protection from the development of primary Sjögren syndrome.25

CCR5 d32 was not involved in susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in a Spanish population, although this polymorphism correlates with the development of lupus nephritis in Spanish SLE patients.26 On the other hand, CCR5 d32 predisposes to later onset of type 1 diabetes.27

CCR5 mediated chemotaxis may favourably affect the bias of Th2 immune response of asthma by induction lymphocytes with Th1 phenotype. Hall et al. found that individuals carrying CCR5 d32 are at reduced risk of developing asthma.28 Furthermore, a transmission disequilibrium test showed similar results for susceptibility to atopy or wheezing.29

CCR2 is mainly expressed by memory T lymphocytes, monocytes, dendritic cells, B cells and basophils. The most commonly studied CCR2 polymorphism is the G190A variant located in the exon 1. It has been shown that its distribution is strongly dependent on ethnicity. Its mutation leads to the substitution of valine by isoleucine (V64I) in the transmembrane region of the protein.

CCR2 mediates the chemotaxis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to the areas of inflammation and because these cells play important roles in insulitis, a mutation in the CCR2 gene may contribute to the susceptibility to the disease. According to these results, the CCR2 gene may be a candidate for the susceptibility locus of T1D.30

No significant difference was found in allelic and genotype frequency of CCR2-64I between SLE patients and controls.31,32

The role of autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of CU is widely discussed. In our study we enrolled patients with positive ASST because of the role of this test as an indicator of the presence of functional autoantibodies.33 We found a borderline dependency between A allele and d32 frequency and susceptibility to CU. We are the first to indicate the possible relation of CU pathogenesis and CCR2 and CCR5 polymorphisms. Similar to the results from the studies on RA subjects, we suggest a preventive role of CCR5 d32 in CU susceptibility. Additionally, we suggest CCR2-64I variant as associated with susceptibility to CU. Furthermore, we proved Gd haplotype combination of CCR2/CCR5 polymorphisms to be preventive for CU occurrence with supposed Aw haplotype combination as a risk factor.

Our findings imply the role of autoimmune components in CU pathogenesis and present CU as a genetically related disorder. In searching for urticaria pathogenesis these components must be taken into account. This point of view will probably simplify further studies on this disease and the general approach to CU treatment. Undoubtedly, the genetics of CU is complex with the involvement of different loci and this area should be explored in further studies on CU pathogenesis.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Patients’ data protectionConfidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingStudy supported by Medical University of Silesia.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.