To estimate the epidemiology of Leber's optic neuropathy (NOHL) in the Region of Madrid.

Material and methodsThe neuro-ophthalmologists who work at public hospitals of the CAM were interviewed by telephone. They were asked about the number of patients with NOHL that they had diagnosed during the time that they had been responsible for the neuro-ophthalmology department of that public hospital. The time worked and the population attended by the hospital were used to calculate the number of inhabitant-years in follow-up by each center during the corresponding period. The basic information of each case (date of birth, mutation, date of visual loss) was registered to avoid duplications.

ResultsOur work estimates a global incidence of 2.34 cases for 10,000,000 inhabitants-year and a prevalence estimated from incidence of one case for each 106.682 inhabitants. This prevalence was very similar in all the studied areas and considerably lower than that reported by other studies.

ConclusionThis work constitutes the first approach to the epidemiology of this disease in Spain. The prevalence of LHON in the region of Madrid, is probably lower than that reported in the literature in other regions. The prevalence and the incidence were homogeneously low in the 26 studied areas.

Estimar la epidemiología (incidencia y prevalencia) de la neuropatía óptica de Leber (NOHL) en la Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid (CM).

Material y métodosLos neuroftalmólogos que trabajan en los hospitales públicos de la CAM fueron entrevistados telefónicamente. Se les preguntó por el número de pacientes con NOHL que habían diagnosticados durante el tiempo que han sido responsables de la consulta de neuroftalmología de ese hospital público. El tiempo trabajado y la población atendida por el hospital se utilizó para calcular el número de habitantes-año en seguimiento por cada centro durante el periodo correspondiente y estimar la incidencia en cada área. La prevalencia estimada a partir de la incidencia (PEI) se calculó considerando que un paciente con NOHL vive unos 40 años con la enfermedad. Se registró la información básica de cada caso cuando estaba disponible (sexo, fecha de nacimiento, mutación, fecha de la pérdida visual) para evitar duplicaciones.

ResultadosNuestro trabajo estima una incidencia global de 2,34 casos por cada 10.000.000 habitantes-año y una PEI de 1 caso por cada 106.682 habitantes. Esta prevalencia es inferior a la referida por otros estudios.

ConclusiónEste trabajo constituye la primera aproximación a la epidemiología de esta enfermedad en España. La prevalencia estimada de la NOHL en la CM es probablemente inferior a la reportada en la literatura en otras regiones. La prevalencia y la incidencia fue homogéneamente baja en las 26 áreas estudiadas.

Estimates of the prevalence of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) are based on studies conducted mainly in Nordic countries.1,2 Epidemiological studies have been published in Italy, England, Holland, Finland, Denmark,1–5 Southern Europe6 and Japan7,8 but, to date, no work has epidemiologically evaluated this pathology in Spain. A meta-analysis estimated that in Europe the prevalence of this disease is in the order of 1/50,000.1

Knowing the epidemiology is important for organising health services taking into account the development of new therapies. Determining prevalence and incidence is difficult because there is no official registry in Spain and patients with LHON, aware of its chronicity and irreversibility, often fail to attend check-ups.

The aim of this study is to use the number of cases diagnosed in each health area to estimate the incidence in each of these districts and to make an overall estimate of the incidence in the region.

Material and methodsStudy populationWe used as a reference the CM database available on the internet, which in 2018 established a population of 6,659,606 inhabitants.9 There are a total of 26 public hospitals that preferentially serve patients from a given area (8 centres belong to group 1, 12 to group 2, and 6 to group 3). There are also 2 pediatric hospitals (Hospital Pediátrico del Hospital Universitario La Paz and Hospital Niño Jesús) that are not assigned to a defined area.9 The non-pediatric support hospitals that do not have a defined area (Hospital de la Cruz Roja and Hospital Santa Cristina) were not included in the present study. To calculate the incidences we used the population assigned to each health area in this document.9

The head of the Neurophthalmology section of the Ophthalmology service of each hospital (or the person with the greatest interest in Neurophthalmology) was contacted by telephone/email and asked about the number of patients diagnosed in the hospital where he/she now practices Neurophthalmology, as well as the length of time he/she has been practising in that institution. This information was supplemented with information obtained through the Leber's Optic Atrophy Association (ASANOL, an umbrella organisation for patients with Leber's optic atrophy).

Study periodGiven that in February 2008 several hospitals were inaugurated in this region, health areas were reorganised and there was a mobilisation of professionals, so 28 February 2008 was considered as the starting point of the study. Patients with a previous diagnosis were not included. In February 2023, professionals were consulted for a second time. We have therefore considered 28 February 2023 as the closing date of the study.

VariablesOnce the patients had been identified, we proceeded to determine which were resident in their current health area and which were imported cases. If the patient came from outside the CM, he/she was excluded. If the patient came from another area of the CM, he/she was assigned to that area to perform the incidence calculations, if he/she had been diagnosed during the period of professional practice of the neuro-ophthalmologist responsible for that area. Otherwise the patient was excluded.

Neuro-ophthalmologists received two calls, one during January 2022 and one during January 2023, and basic information was collected for each patient: date of birth, date of debut of visual loss, sex, mutation. The date of birth was used as a control to avoid duplication.

AnalysisThe time at which the neuro-ophthalmologist started working in the neuro-ophthalmology section of the corresponding hospital was used to determine the time spent at the hospital. This information was multiplied by the number of inhabitants assigned to that health area to determine the number of inhabitant-years followed in that area.

Once the number of patients per year followed by each neuro-ophthalmologist in their hospital had been calculated, the incidence was calculated by dividing the number of cases diagnosed from that area by the number of patient-years followed in that area, and the incidence in the corresponding area was calculated. Only those patients whose disease debut occurred during the period of time that the head of the neuroophthalmology section worked in that health area were considered to be included. Cases with a debut prior to that date were excluded. A prospective incidence calculation was also performed for the year 2022.

The calculation of the estimated prevalence was performed as follows. The prevalence depends on the incidence of the disease and the length of time the patient is alive with the disease. In Madrid, life expectancy is above 80 years.10 For simulation purposes it was considered that a patient with LHON lives about 40 years with the disease, debuting at around 30 years of age4 and has a life expectancy of about 70 years.11 The prevalence was therefore calculated by multiplying the incidence by 40.

Ethical aspectsThe study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the bioethics committee of the Universidad Francisco de Vitoria (identification code: 30/2019).

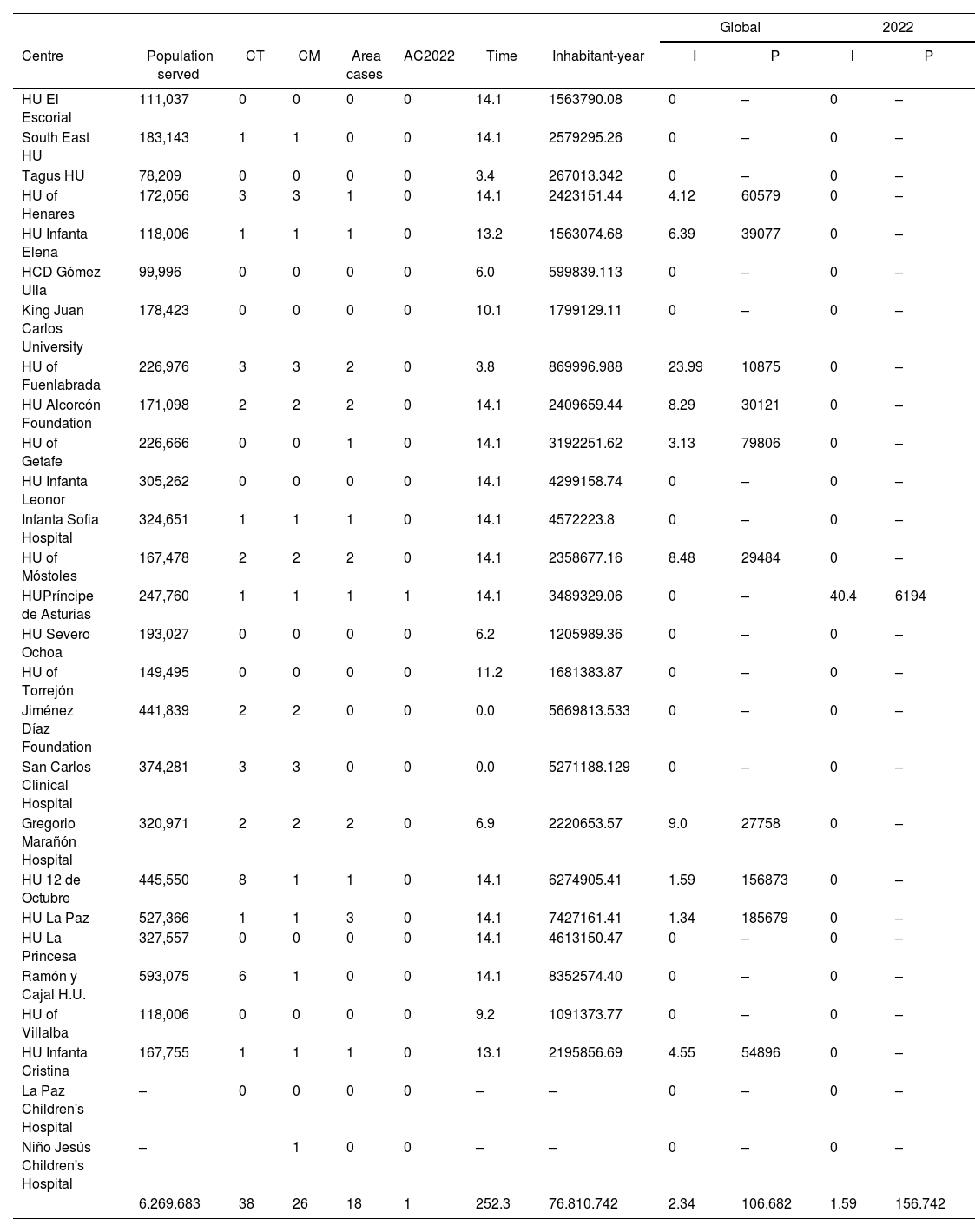

ResultsGlobal estimates (ambispective)All the ophthalmologists surveyed agreed to participate in the study, except for the neuro-ophthalmologist at the Puerta de Hierro hospital, so this population was excluded, and the calculations were performed on 6,269,683 inhabitants. Most of the health areas studied do not have any cases of their own, so the incidence in most of the health areas studied is zero. (Table 1) In the large hospitals of the Community of Madrid most cases are imported. Fuenlabrada hospital had the highest incidence. Three cases have been diagnosed in this hospital (two from the area and one from the area served by Getafe in recent years). This hospital, with 24 cases per 10 million patient-years, is the centre with the highest incidence.

Summary of the number of LHON cases assessed in each hospital.

| Global | 2022 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre | Population served | CT | CM | Area cases | AC2022 | Time | Inhabitant-year | I | P | I | P |

| HU El Escorial | 111,037 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.1 | 1563790.08 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| South East HU | 183,143 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14.1 | 2579295.26 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Tagus HU | 78,209 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.4 | 267013.342 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| HU of Henares | 172,056 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 14.1 | 2423151.44 | 4.12 | 60579 | 0 | – |

| HU Infanta Elena | 118,006 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 13.2 | 1563074.68 | 6.39 | 39077 | 0 | – |

| HCD Gómez Ulla | 99,996 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.0 | 599839.113 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| King Juan Carlos University | 178,423 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.1 | 1799129.11 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| HU of Fuenlabrada | 226,976 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3.8 | 869996.988 | 23.99 | 10875 | 0 | – |

| HU Alcorcón Foundation | 171,098 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 14.1 | 2409659.44 | 8.29 | 30121 | 0 | – |

| HU of Getafe | 226,666 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 14.1 | 3192251.62 | 3.13 | 79806 | 0 | – |

| HU Infanta Leonor | 305,262 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.1 | 4299158.74 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Infanta Sofia Hospital | 324,651 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14.1 | 4572223.8 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| HU of Móstoles | 167,478 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 14.1 | 2358677.16 | 8.48 | 29484 | 0 | – |

| HUPríncipe de Asturias | 247,760 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14.1 | 3489329.06 | 0 | – | 40.4 | 6194 |

| HU Severo Ochoa | 193,027 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.2 | 1205989.36 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| HU of Torrejón | 149,495 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.2 | 1681383.87 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Jiménez Díaz Foundation | 441,839 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5669813.533 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| San Carlos Clinical Hospital | 374,281 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5271188.129 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Gregorio Marañón Hospital | 320,971 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6.9 | 2220653.57 | 9.0 | 27758 | 0 | – |

| HU 12 de Octubre | 445,550 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14.1 | 6274905.41 | 1.59 | 156873 | 0 | – |

| HU La Paz | 527,366 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 14.1 | 7427161.41 | 1.34 | 185679 | 0 | – |

| HU La Princesa | 327,557 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.1 | 4613150.47 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Ramón y Cajal H.U. | 593,075 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14.1 | 8352574.40 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| HU of Villalba | 118,006 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.2 | 1091373.77 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| HU Infanta Cristina | 167,755 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 13.1 | 2195856.69 | 4.55 | 54896 | 0 | – |

| La Paz Children's Hospital | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Niño Jesús Children's Hospital | – | 1 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | |

| 6.269.683 | 38 | 26 | 18 | 1 | 252.3 | 76.810.742 | 2.34 | 106.682 | 1.59 | 156.742 | |

Abbreviations: HU: University Hospital, TC: total cases, CM: community of Madrid cases, Area cases: cases in the area served by that hospital, I: incidence expressed in cases per 10,000,000 patient-years, P: prevalence assuming median survival of 40 years from the time of diagnosis, expressed in cases per number of inhabitants.

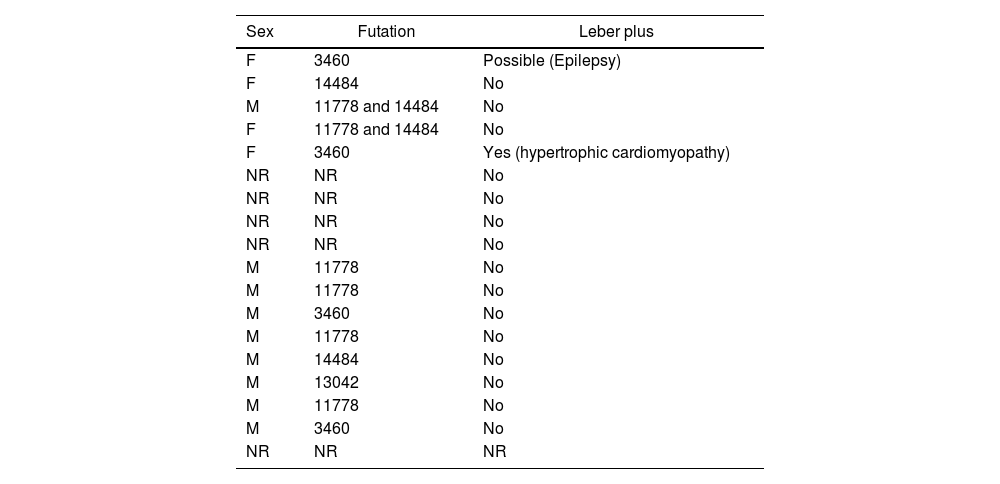

The overall incidence in CM was 2.34 cases per 10 million patient-years. Taking into account a survival of about 40 years with the disease, the prevalence would be 1 case per 106,682 patients. (Table 1) In 5 of the 18 cases the neurophthamologist was not able to provide details about the case. The basic data of the remaining 13 cases (mutation and sex) are summarised in Table 2. Only two patients had manifestations compatible with Leber plus.

Epidemiological data of the patients studied. F: female; M: male; NR: not remembered.

| Sex | Futation | Leber plus |

|---|---|---|

| F | 3460 | Possible (Epilepsy) |

| F | 14484 | No |

| M | 11778 and 14484 | No |

| F | 11778 and 14484 | No |

| F | 3460 | Yes (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) |

| NR | NR | No |

| NR | NR | No |

| NR | NR | No |

| NR | NR | No |

| M | 11778 | No |

| M | 11778 | No |

| M | 3460 | No |

| M | 11778 | No |

| M | 14484 | No |

| M | 13042 | No |

| M | 11778 | No |

| M | 3460 | No |

| NR | NR | NR |

During the last year, only one case of LHON has been diagnosed in patients resident in the CAM. This figure would imply an incidence of 1.59 cases per 10 million population-years. Considering a survival of about 40 years from the diagnosis of the disease, this incidence would imply a PEI of one case per 156,742 inhabitants.

In 5 cases the practitioner was not able to retrieve the case data, in the remaining 13 cases 9 were male and 4 were female (Table 2).

DiscussionDespite all the limitations, this is the first study that attempts to estimate the epidemiology of LHON in Spain and one of the few carried out worldwide. We have estimated an incidence of 2.34 cases per 10 million patient-years and a prevalence of 1 case per 106,682 inhabitants; lower than those reported in previous literature.

In Spain, there is no reference centre for hereditary optic neuropathies, but three hospitals in Madrid have grouped together a larger number of cases. These hospitals are the Doce de Octubre Hospital (reference centre for mitochondrial diseases), the Jiménez Diaz Foundation, which has a strong clinical genetics department, and the Ramón y Cajal Hospital, which has participated in international clinical trials in relation to this disease. As can be seen in Table 1, most of the cases treated in tertiary hospitals are imported from other Spanish regions.

Cases of this disease have been reported in recent years in connection with increased alcohol consumption due to social isolation during de COVID-19 lockdown. However, there does not appear to have been an increase in incidence in CM.12 In one of the patients, conversion occurred in 2021 after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 (already published).13 These figures do not suggest that COVID or vaccines have had an impact on disease incidence.

To make our results comparable with the literature, we decided to estimate prevalences. There are precise estimates of the mean age of disease onset (25 years for males and 33 years for females).11 However, there are no published data on the life expectancy of these patients, although a recent communication shows that these patients have a higher risk of heart disease, atherosclerosis, stroke, dementia, epilepsy, demyelinating disorders, neuropathy and alcohol-related disorders. Therefore, it seems likely that they have a somewhat shorter longevity than the general population.4

This is one of the few papers to provide incidence figures. Most epidemiological studies report prevalences. Incidence figures would allow us to understand the influence that environmental factors have on the penetrance of the disease, as well as helping to organise health resources, given that there is believed to be a window period for the application of current therapies.

We have considered some basic patient data (date of birth, sex, mutation) to try to avoid duplications. A patient with a severe and rare disease may visit several hospitals, be registered several times and enter duplicate statistics. In Japan, a reduction in the prevalence of the disease has been attributed to the fact that these duplications were initially not taken into account.7,8

There is a significant lack of homogeneity in the way these studies have been conducted and this information has been reported. The published series are in many cases from reference centres.14 With this methodology, certain patients not referred to these centres may not be recorded, leading to an underestimation of the figures.

When prevalence is estimated only from information from a single hospital centre,14,15 there may be a tendency to include all cases diagnosed in the hospital, and this is not always correct because a referral hospital attracts cases from other areas. Relatives of the index case of a pedigree, residing in other locations, may come to that hospital and this could lead to an overestimation of the figures. In the methodology section of most articles it is not very clear whether the place of residence of the diagnosed patient has been considered or whether all members of a pedigree have been included directly. This attritional bias may lead to overestimation of prevalences. For example, in our study, had we not excluded patients from other communities or duplicate cases, we would have located a total of 38 patients instead of 18, doubling the incidence and prevalence figures obtained and placing us much closer to those reported in the literature.

We found a high level of homogeneity in the incidence rates in the different areas studied. The fact that the study was carried out in an autonomous community with a good provision of health resources, that the cases were taken into account both in the hospitals that informally function as reference centres and in the hospitals of origin, and that we found homogeneously low incidence figures, leads us to believe that the incidence and prevalence of this disease in our region is lower than that reported in the literature.

It is also possible that interest in the disease is higher in populations with higher incidences and that there is some publication bias in the literature. It is therefore possible that the literature overestimates the frequency of this pathology. In more southern populations, certain environmental factors could lead to a lower incidence,2,3 the reduction of smoking and moderation of alcohol consumption may be favouring a decrease in incidence.

It can be argued that the retrospective nature of our study leads to an underestimation of the figures. However, we believe that the estimated incidences during the year 2022 have been prospective, as ophthalmologists were contacted both in early 2022 and early 2023. It is likely that memory bias had very little influence on this estimate. The year 2022 saw the debut of only one case of LHON in CM, an incidence of this magnitude would justify a prevalence (assuming a 40-year survival with the disease) of only one case per 166,490.

A possible limitation of our study is that only ophthalmologists were surveyed. This disease is diagnosed and followed by neurologists and ophthalmologists. However, we believe that since the patient requires visual field and optical coherence tomography examinations for diagnosis, and this technology is usually available in ophthalmology rather than neurology departments, it is rare that the disease is diagnosed without the involvement of an ophthalmologist. Similarly, we believe that not including private hospitals is not a major limitation, as in the case of severe diseases whose treatment is expensive and chronic patients in Spain tend to turn to the public system.

It is very striking that the incidence in the last year is so low. Ophthalmologists and neurologists are now much more aware of the disease. Improved diagnostic technology, easier access to genetic testing, as well as a surge of interest in the availability of new therapies, should have led to an increase in the incidence of the disease, but this has not occurred.

Recent studies tend to consider that the mutations that cause LHON are much more frequent than previously thought, and that the penetrance of the disease is very low.16,17 There is a tendency to think that the penetrance of a mutation in the general population is much lower than in those families where the mutation is present and there is an affected member.16,17 This is thought to be because certain genes or haplotypes may favour conversion. Some researchers suggest that the distribution of haplotypes may account for the low prevalences reported in some regions.6 We found a higher proportion of females (4 of the 13 cases identified) than usual. This over-representation of women could be due to changes in the roles and behaviours of men and women (decrease in smoking in men and increase in women), but it is difficult to speculate on this fact, given the low number of cases collected.

In summary, our study estimates incidence and prevalence figures lower than those published in other countries. It is possible that this gap is attributable to under-diagnosis, but we believe that in our environment this should not be higher than in other regions. Neither the COVID nor the massive vaccination campaign carried out to combat this disease, nor the interest aroused by the appearance of new therapies seem to have increased the incidence of this disease in our environment. We hope that these figures will serve as a starting point for further epidemiological studies.1

FundingThis work is funded by the Spanish National Organisation for the Blind (ONCE): grant 2020/1519.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interests were declared by the authors.

The authors would like to thank ASANOL (Leber's Optic Nerve Atrophy Association) and all the professionals who, although not listed as authors, participated in the study. The following is a list of all the professionals who were surveyed for this study: Julio González-Martín-Moro (MD, PhD, Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario del Henares, Madrid; Department of Health Sciences, Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, Madrid); María Luisa Luque Valentín Fernández (Department of Health Sciences, Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, Madrid; Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario del Escorial, Madrid); Elena del Fresno (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario del Tajo, Madrid); María Castro Rebollo (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario del Henares, Madrid); Paula Bañeros Rojas (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla, Madrid); Ester Arranz (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos, Madrid); Borja Maroto Rodríguez (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada, Madrid); Julio Yangüela (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Fundación de Alcorcón, Madrid); Estrella López Carril (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid); Icíar Irache (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor, Madrid); Isabel Cortés (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía, Madrid); Mar González Manrique (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario de Móstoles, Madrid); Consuelo Gutiérrez Ortiz (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Madrid); Cristina Montón Jiménez (Department of Ophthalmology, Severo Ochoa University Hospital, Madrid); Irene Canal Fontcuberta (Department of Ophthalmology, Torrejón University Hospital, Madrid); Laura Cabrejas Martínez (Department of Ophthalmology, Fundación Jiménez Diaz University Hospital, Madrid); Blanca Domingo Gordo (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid); Enrique Santos Bueso (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid); Pilar Rojas (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid); Alberto Reche (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Doce de Octubre, Madrid); Teresa Gracia (Department of Ophthalmology, Doce de Octubre University Hospital, Madrid); Jesús Fraile Maya (Department of Ophthalmology, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid); Susana Noval (Department of Ophthalmology, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid); Andrés Pérez Casas (Department of Ophthalmology, La Princesa University Hospital, Madrid); Francisco Muñoz Negrete (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid); Germán Ancochea Díaz (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina, Madrid); Natalia Blanco Calvo (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Niño Jesús, Madrid); Carolina Rabanaque (Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Universitario del Sureste, Madrid).