To report a pilot experience of telemedicine in Ophthalmology in Open-care modality (i.e. direct video call), in a confinement period due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

MethodsDescriptive study of the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients attended in a 10-week confinement period. Reported satisfaction of the participating patients and doctors was evaluated through an online survey.

ResultsIn the 10-week period, 291 ophthalmologic telemedicine consultations were performed. The main reasons for consultation were inflammatory conditions of the ocular surface and eyelids (79.4%), followed by administrative requirements (6.5%), non-inflammatory conditions of the ocular surface (5.2%), strabismus suspicion (3.4%) and vitreo-retinal symptoms (3.1%). According to previously defined criteria, 22 patients (7.5%) were referred to immediate face-to-face consultation. The level of satisfaction was high, both in doctors (100%) and in patients (93.4%).

ConclusionsOpen-care modality of telemedicine in Ophthalmology during the pandemic period is a useful instrument to filter potential face-to-face consultations, either elective or emergency, and potentially reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection.

Reportar una experiencia piloto de atención por telemedicina en la especialidad de oftalmología, en el periodo de confinamiento por la pandemia COVID-19.

MetodosEstudio descriptivo. Se describen características demográficas y clínicas de pacientes atendidos en periodo de confinamiento de 10 semanas. Se evalúa la satisfacción de los pacientes y médicos participantes mediante una encuesta online.

ResultadosEn las primeras 10 semanas, se realizaron 291 atenciones de telemedicina oftalmológica. Los principales motivos de consulta fueron afecciones inflamatorias de la superficie ocular y párpados (79,4%), seguido de requerimientos administrativos (6,5%), afecciones no inflamatorias de la superficie ocular (5,2%), sospecha de estrabismo (3,4%) y síntomas vitreoretinales (3,1%). 22 pacientes (7,5%) fueron derivados a atención presencial inmediata. El nivel de satisfacción con la prestación fue alto, tanto en médicos (100%) como en pacientes (93,4%).

ConclusionesLa atención oftalmológica por telemedicina en periodo de pandemia es un instrumento de utilidad para realizar un filtro de potenciales consultas presenciales, ya sea electivas o de urgencia, y potencialmente reducir riesgo de contagio por COVID-19.

Telemedicine is the name given to the use of information and communication technologies for remote medical care, through the transmission of texts, sounds and images.1 In the last 20 years, it has demonstrated its usefulness in aspects such as prevention, diagnosis, treatment and monitoring in various specialties, especially in developing countries with high percentage of rural areas. It has increased the care coverage of population, reduced costs and improved the follow-up of pathologies.2

The use of Telemedicine in Ophthalmology (TMO) including transmission of photographs, videos and remote evaluation by a specialist has been reported in screening and monitoring programs for diabetic retinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity and glaucoma.3–6

The use of TMO in Open Care modality or tele-consultation (i.e. direct synchronous video call from patient to doctor) has been scarce, probably due to the need of direct examination with slit-lamp microscopy, fundoscopy and ocular tonometry, for better diagnostic precision.7 To our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating this modality of TMO in the national setting.

The need of using of TMO in teleconsultation modality arises due to the epidemiological contingency due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has imposed restrictions on elective medical care in most medical centers. The ophthalmology specialty has been reported among those with highest risk of Covid-19 infection, either due to the close contact with the patient or due to contamination of the examination instruments.8–10

The OC-TMO was established in our Ophthalmology Service in a pandemic situation as an exceptional form of care, which seeks the following objectives:

- -

To reduce the patient's anxiety through active listening, support and expert opinion.

- -

To screen for severity criteria and risk factors which might warrant immediate face-to-face care.

- -

To resolve administrative needs (i.e. certificates, prescription renewals).

- -

To deliver basic therapeutic recommendations.

- -

To monitor the clinical evolution of the patient.

The OC-TMO was implemented through the Telemedicine Service of the UC-Christus Health Network (www.ucchristus.cl), over a period of 10 weeks between March and June 2020, while elective ambulatory ophthalmology care was partially or fully suspended.

The teleophthalmology care framework includes: 30-minute video call, previously scheduled with an accredited specialist doctor, through the Zoom© platform (Zoom Video Communications Inc); informed consent of the conditions of the provision, confidentiality clause, obligatory registration in the clinical record (single electronic chart that includes all in-patient care in the UC-Christus Health Network), option of prescription with electronic signature, and a direct contact for the professional for follow-up (email and/or telephone).

A Committee made up of ophthalmologists from the Department prepared a Clinical Guide for the practice of Ophthalmological Telemedicine, based on discussions and analysis of ethical, medical-legal, technological and clinical aspects of the activity. This guide was used to train ophthalmologists who performed teleconsultations. It includes interview techniques, inspection protocol for on-screen inspection eye examination, referral and follow-up criteria, among other aspects.

The study included all of the patients who seek attention via teleconsulting during the study period. No exclusion criteria were applied.

Demographic and clinical data were recorded by each doctor after the consultation. Assessment of care by participating patients and physicians were evaluated through an anonymous online survey (surveymonkey.com).

The study was carried out according to the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institution's Ethics Committee. Participants signed an online informed consent.

ResultsDemographicsDuring the ten-week study period, 291 teleophthalmology consultations were performed by 12 ophthalmologists. 58.1% of the patients were female, with an average age of 38.0 ± 22.5 years (range 0–90 years).

In terms of the geographic location of the patients attended, 85.4% were from the Metropolitan Region, 13.5% from other provinces, and 1.1% from abroad.

ClinicalsFor 74.5% of patients, the consultation represented their first within the UC-Christus Ophthalmology Service. Of the patients who had previously attended consultations in our Service (25.5%), 49.3% had already consulted at least once with the same doctor seen in the teleconsultation. The average time of each teleconsultation was 21 ± 8 min.

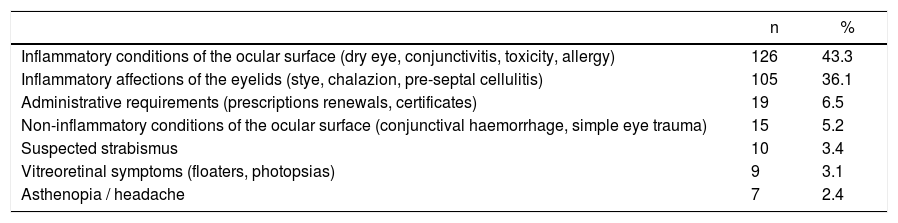

The reasons for consultation are shown in Table 1, categorized by evaluated symptoms and signs. The most common reasons for consultation are inflammatory conditions of the ocular surface (43.3%) and eyelids (36.1%).

Categorization of reasons for consultation.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory conditions of the ocular surface (dry eye, conjunctivitis, toxicity, allergy) | 126 | 43.3 |

| Inflammatory affections of the eyelids (stye, chalazion, pre-septal cellulitis) | 105 | 36.1 |

| Administrative requirements (prescriptions renewals, certificates) | 19 | 6.5 |

| Non-inflammatory conditions of the ocular surface (conjunctival haemorrhage, simple eye trauma) | 15 | 5.2 |

| Suspected strabismus | 10 | 3.4 |

| Vitreoretinal symptoms (floaters, photopsias) | 9 | 3.1 |

| Asthenopia / headache | 7 | 2.4 |

7.5% of the patients (n = 22) were referred to face-to-face consultation, according to previously defined severity criteria and/or risk factors. The clinical-anamnestic findings that lead to face-to-face consultation were palpebral cellulitis (n = 6), suspected scleritis/keratitis (n = 5), eye trauma (n = 4), suspected strabismus (n = 4) and vitreoretinal symptoms (n = 3).

Pharmacological treatment with at least one drug was prescribed in 83% of the patients, with the most frequently prescribed were ocular lubricants (35.6%), combined antibiotic and corticosteroid eye drops (28.4%), and surface corticosteroids. (17.1%).

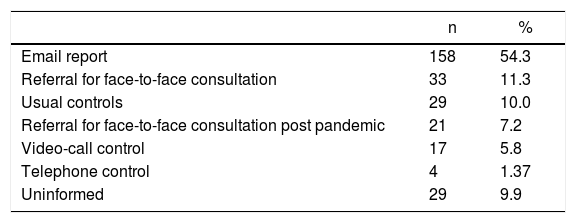

The indication of subsequent controls, provided by the doctors to the patients, are indicated in Table 2. The main control route recommended was the report of symptoms via email (54.3%).

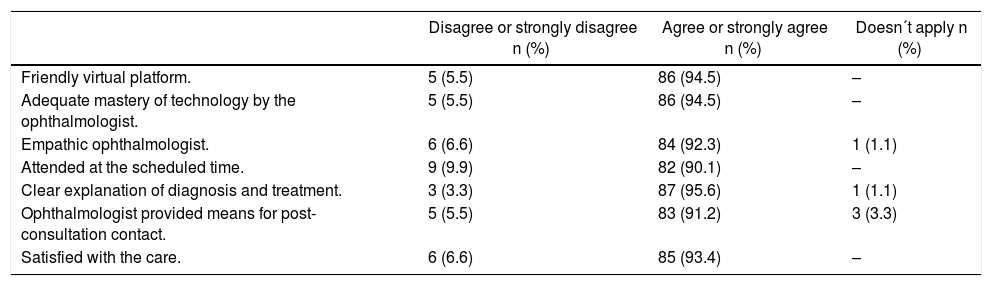

Patient evaluation survey91 patients answered the evaluation questionnaire, comprising 31.2% of those who were sent an email invitation to answer the survey. Most of the patients who answered the survey (93.4%) reported being satisfied with the care, and a similar number agreed with other statements regarding satisfactory care, as shown in Table 3.

Agreement with quality of care statements in telemedicine, in the patient evaluation survey.

| Disagree or strongly disagree n (%) | Agree or strongly agree n (%) | Doesn´t apply n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Friendly virtual platform. | 5 (5.5) | 86 (94.5) | – |

| Adequate mastery of technology by the ophthalmologist. | 5 (5.5) | 86 (94.5) | – |

| Empathic ophthalmologist. | 6 (6.6) | 84 (92.3) | 1 (1.1) |

| Attended at the scheduled time. | 9 (9.9) | 82 (90.1) | – |

| Clear explanation of diagnosis and treatment. | 3 (3.3) | 87 (95.6) | 1 (1.1) |

| Ophthalmologist provided means for post-consultation contact. | 5 (5.5) | 83 (91.2) | 3 (3.3) |

| Satisfied with the care. | 6 (6.6) | 85 (93.4) | – |

Regarding to the experience of care, the majority of patients considered teleophthalmology care to be useful (96.7%) and stated that they would subsequently make use of and/or recommend teleophthalmology care (94.5%). 17.6% of those who answered considered that they need a second consultation.

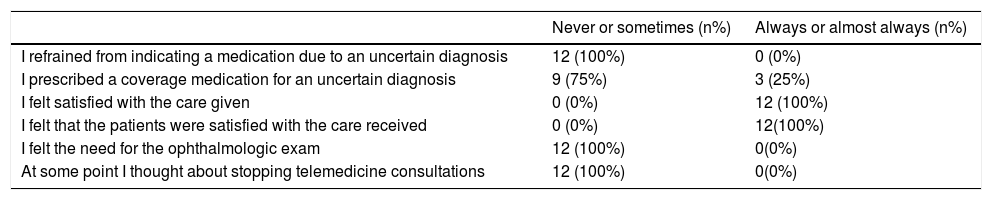

Physician evaluation survey12 ophthalmologists answered the evaluation questionnaire, corresponding to 100% of those who performed teleconsultations in the study period.

The technological resources were evaluated on a scale of 1–5, and the average rating obtained was 4.4, with the scheduling system and the zoom platform being the best evaluated at 4.7, the electronic prescriptions next at 4.3, and finally the electronic medical records scored 3.9.

Regarding to the care provided, 100% of the ophthalmologists felt satisfied and believed that the patients were also mostly or always satisfied with the care provided. Table 4 specifies the frequency of the statements.

Frequency distribution of behavior in teleophthalmology by participating physicians.

| Never or sometimes (n%) | Always or almost always (n%) | |

|---|---|---|

| I refrained from indicating a medication due to an uncertain diagnosis | 12 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| I prescribed a coverage medication for an uncertain diagnosis | 9 (75%) | 3 (25%) |

| I felt satisfied with the care given | 0 (0%) | 12 (100%) |

| I felt that the patients were satisfied with the care received | 0 (0%) | 12(100%) |

| I felt the need for the ophthalmologic exam | 12 (100%) | 0(0%) |

| At some point I thought about stopping telemedicine consultations | 12 (100%) | 0(0%) |

In relation to the prospects of telemedicine, 83% of doctors considered that it is a tool that will be maintained in the future, and 66.7% considered continuing to attend certain patients in this modality after the pandemic. Other modalities of telemedicine were considered potentially useful: remote consultation (100%); emergency triage (92%); chronic patients control (92%); academic tool for seminars (92%) and resident supervision (41.7%).

DiscussionThe present study is, to our knowledge, the first report of a pilot experience of open care by telemedicine in the specialty of ophthalmology in our setting.

Prior to the clinical implementation of ophthalmic teleconsultations, a committee of ophthalmologists with experience and formal training in bioethics, psychology, and the subspecialties of cornea, glaucoma, retina, and pediatric ophthalmology, reviewed the ethical, legal, and clinical aspects involved in this activity, and elaborated a clinical and ethical guideline for the activity.11,12

Taking into account that of face-to-face consultations in our Service were suspended during the study period, the number of teleconsultations was low (approximately 1.7% of the monthly average of attentions). This may be due to the fact that OC-OTM is a totally new and unprecedented service not widely known among patients, in addition to not being covered by health insurance, that cover 98% of the Chilean population.13

Technological resources used were well evaluated, both by doctors and by patients, and the degree of satisfaction with the service was high, despite being a pioneer experience in the field of ophthalmology.

The main reasons for consultation were inflammatory conditions of the ocular surface and eyelids. This, in addition to the few clinical elements available to formulate diagnostic hypotheses and a therapeutic plan, must be considered when defining which proficiencies are necessary to perform ophthalmic teleconsultations.

It is essential to consider OC-TMO as part of an integrated system of care, which necessarily includes a longitudinal follow-up of patients through digital channels, as well as an expedited referral system for face-to-face care, either delayed (post-pandemic) or immediate if required, according to previously defined risk and severity factors.

Exceptional situations require exceptional measures. Although OC-TMO has important limitations, this study validates it as a screening tool for ocular pathologies, as well as an important method to relieve patient´s stress about having ocular symptoms with unknown implications, to reduce the number of face-to-face consultation, and subsequently to reduce the risk of Covid-19 infection.14,15

According to our pilot study, we would suggest the following elements as essential elements for optimal teleophthalmology care:

- -

Health Insurance Coverage, both public and private. This point can give better and horizontal access to our patient for care.

- -

Guarantee of adequate confidentiality during the videocall and clinical data-recording platform provided by the health institution.

- -

Training of participating physicians in videoconferencing technologies; virtual communication skills; diagnosis and treatment of conditions of the ocular surface; severity and referral criteria.

- -

Education of patients regarding the limitations of and indications of the attention, and signing of informed consent.

- -

Virtual monitoring and follow-up protocol (email, videocalls) of the consultations realized.

- -

Record of attentions registered in the same clinical chart of face-to-face care.

- -

Expedited referral system to immediate face-to-face care if the suspected pathology required.

Our study consider the following limitations:

- -

The low percentage of patients who answered the evaluation survey, possibly due to having previously been invited to answer a survey designed by the UC-Christus Health Network for all patients treated by TM across all specialties.

- -

Given the situation of confinement and the descriptive nature of the study, it was not possible to have an in-person examination of all the patients attended by the remote way, to double confirm the diagnostic hypotheses, or the therapeutic efficacy of the prescribed treatment after the consultation.

In conclusion, ophthalmologic telemedicine in open-care modality during pandemic period is a useful instrument for screening, potentially reducing the number of face-to-face consultations and the risk of Covid-19 infection. It also provides simple therapeutic responses, potentially reducing physical and psychical patient’s discomfort, with a high rate of satisfaction for both patients and physicians.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We would like to acknowledge Isabel Rao Shuai for her assistance in translation of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Arntz A, Khaliliyeh D, Cruzat A, Rao X, Rocha G, Grau A, et al. Telemedicina en oftalmología durante la pandemia de COVID-19: una experiencia piloto. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2020;95:586–590.