To explore the health effects of a community health intervention on older people who are isolated at home due to mobility problems or architectural barriers, to identify associated characteristics and to assess participants’ satisfaction.

DesignQuasi-experimental before–after study.

SettingFive low-income neighbourhoods of Barcelona during 2010–15.

Participants147 participants, aged ≥59, living in isolation due to mobility problems or architectural barriers were interviewed before the intervention and after 6 months.

InterventionPrimary Health Care teams, public health and social workers, and other community agents carried out a community health intervention, consisting of weekly outings, facilitated by volunteers.

MeasurementsWe assessed self-rated health, mental health using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), and quality of life through the EuroQol scale. Satisfaction with the programme was evaluated using a set of questions. We analysed pre and post data with McNemar tests and fitted lineal and Poisson regression models.

ResultsAt 6 months, participants showed improvements in self-rated health and mental health and a reduction of anxiety. Improvements were greater among women, those who had not left home for ≥4 months, those with lower educational level, and those who had made ≥9 outings. Self-rated health [aRR: 1.29(1.04–1.62)] and mental health improvements [β: 2.92(1.64–4.2)] remained significant in the multivariate models. Mean satisfaction was 9.3 out of 10.

ConclusionThis community health intervention appears to improve several health outcomes in isolated elderly people, especially among the most vulnerable groups. Replications of this type of intervention could work in similar contexts.

Explorar los efectos sobre la salud de una intervención de salud comunitaria en personas mayores aisladas en casa debido a problemas de movilidad o a barreras arquitectónicas, identificar las características asociadas y evaluar la satisfacción de las personas participantes.

DiseñoEstudio cuasi-experimental antes-después.

EmplazamientoCinco barrios de baja renta de Barcelona durante 2010-15.

ParticipantesSe entrevistó a 147 participantes, ≥59 años, antes y 6 meses después de la intervención.

IntervenciónEquipos de atención primaria, trabajadores sociales, de salud pública y otros agentes comunitarios desarrollaron una intervención que consistía en salidas semanales, facilitadas por voluntarios.

MedicionesSe evalúo la salud autopercibida, la salud mental utilizando la escala GHQ-12 y la calidad de vida mediante la escala EuroQol. La satisfacción se evaluó mediante un conjunto de preguntas. Analizamos los datos previos y posteriores con pruebas de McNemar y modelos de regresión lineal y de Poisson ajustados.

ResultadosA los 6 meses, los participantes mostraron mejoras en la salud percibida, en la salud mental y en la reducción de la ansiedad. Las mejoras fueron mayores entre las mujeres, las personas que no habían salido de casa durante ≥4 meses, las de bajo nivel educativo y las que habían realizado ≥9 salidas. La salud percibida (aRR: 1,29 [1,04-1,62]) y las mejoras en salud mental [(β: 2,92 [1,64-4,2]) permanecieron significativas en los modelos multivariados. La satisfacción media fue de 9,3 sobre 10.

ConclusiónEsta intervención de salud comunitaria parece mejorar varios resultados de salud en las personas mayores aisladas, especialmente en los grupos más vulnerables. Replicar este tipo de intervención podría funcionar en contextos similares.

Social isolation among the elderly is associated with increased mortality, poorer self-rated health, lower quality of life and greater risk of dementia.1,2 Social isolation refers to the lack of structural and functional social support that includes (a) the objective assessment of its size and frequency, and (b) the subjective assessment of the perceived value of emotional, instrumental and informational support provided by others.3 Loneliness is closely related to social isolation and has been defined as the subjective experience of the absence or loss of companionship which is always involuntary.3–5 Loneliness and social isolation are more prevalent among older people due to factors such as the death of relatives and friends, loss of social roles (children growing up and/or retirement) and increased prevalence of chronic or disabling illnesses.6

In elderly, difficulty in engaging in community activities has been associated with self-perceived depression and loss of interest in pleasurable activities.7 Conversely, elderly people who have more social relationships and social participation have better mental, social and physical health.3 Some studies have shown that interventions to promote social participation for older people can prevent loneliness and social isolation associated among the least wealthy groups.5,8–10 Besides that, architectural barriers that hinder or prevent people from going out on their own, have been described as factors associated with the perception of loneliness.4

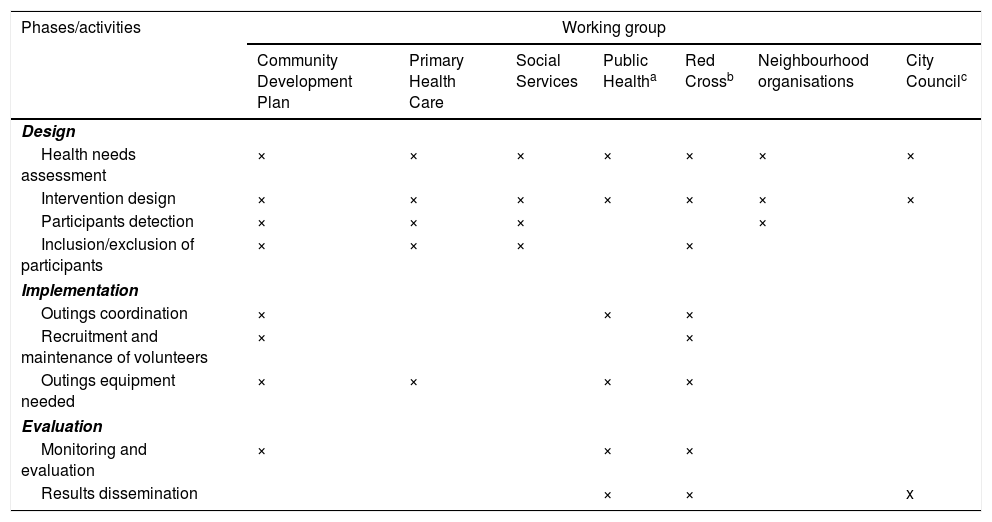

In Barcelona in 2016, 31.6% of buildings did not have an elevator, and this percentage was higher in the most deprived neighbourhoods.11 In addition, in 2018, 21.6% of the citizens of Barcelona were over 65 years old, and 25.6% of them were living alone.12 Since 2007, the municipal strategy Barcelona Health in the Neighbourhoods has been working to reduce health inequalities through community health interventions.13,14 As part of this community health strategy, a working group composed by Community Development Plan, Primary Health Care, Social Services, Barcelona Public Health Agency, Health Department of Barcelona City Council, Red Cross in Barcelona and neighbourhoods’ organisations (Table 1), designed and conducted an intervention consisted of weekly outings in five deprived neighbourhoods in Barcelona, to alleviate loneliness among older people who were living in isolation in their homes for long periods, mainly due to mobility limitations and/or the lack of an elevator in their buildings. The objective of this paper is to: (1) explore the effects of the intervention on health outcomes, (2) identify what characteristics of the participants and the intervention are associated with health effects and (3) assess participants’ satisfaction.

Description of the activities carried out by the working group to develop a community health intervention from 2010 to 2015.

| Phases/activities | Working group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Development Plan | Primary Health Care | Social Services | Public Healtha | Red Crossb | Neighbourhood organisations | City Councilc | |

| Design | |||||||

| Health needs assessment | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Intervention design | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Participants detection | × | × | × | × | |||

| Inclusion/exclusion of participants | × | × | × | × | |||

| Implementation | |||||||

| Outings coordination | × | × | × | ||||

| Recruitment and maintenance of volunteers | × | × | |||||

| Outings equipment needed | × | × | × | × | |||

| Evaluation | |||||||

| Monitoring and evaluation | × | × | × | ||||

| Results dissemination | × | × | x | ||||

We used a quasi-experimental before–after design. The study analyses the intervention carried out from May 2010 to December 2015 in five disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Barcelona. Neighbourhoods were prioritised according to the Family Disposable Income Index in 201015 and prevalence of older people living alone.11

ParticipantsThe inclusion criteria were people aged ≥59 years old and who had been living in isolation in their homes for two or more months due to mobility limitations and/or lack of an elevator in their buildings. Bedridden persons, persons with severe dementia and those without medical authorisation to leave their home were excluded. Primary health care teams contributed to establish and assessed health-related exclusion criteria. Services usually in contact with the target population in the neighbourhoods, such as Primary Health Care, Social Services, Community Development Plan and neighbourhoods’ organisations, were responsible for detecting people with inclusion criteria (Table 1).

InterventionThe intervention was developed by a working group who made the health need assessment and intervention design (Table 1). This consisted of weekly outings, facilitated by volunteers using a portable climbing wheelchair. The coordination and recruitment of volunteers was mainly in charge of the Community Development Plan and Red Cross. Equipment needed to carry out the outings such as wheelchairs and a portable climbing wheelchair was mainly provided by primary health care, Red Cross and the Barcelona Public Health Agency (Table 1). The intervention promoted social support and participation through activities proposed by the participants, such as visiting friends, short walks, going to the market or attending church.16 In addition to the individual weekly outings, group outings were conducted once a month to foster new social relationships among participants, such as city sightseeing, cultural activities and group dynamics. The evaluation process was mainly in charge of the Barcelona Public Health Agency, Community Development Plan and Red Cross (Table 1). Economic and human resources to maintain the sustainability of the intervention came from Barcelona Public Health Agency and Health Department of Barcelona City Council.

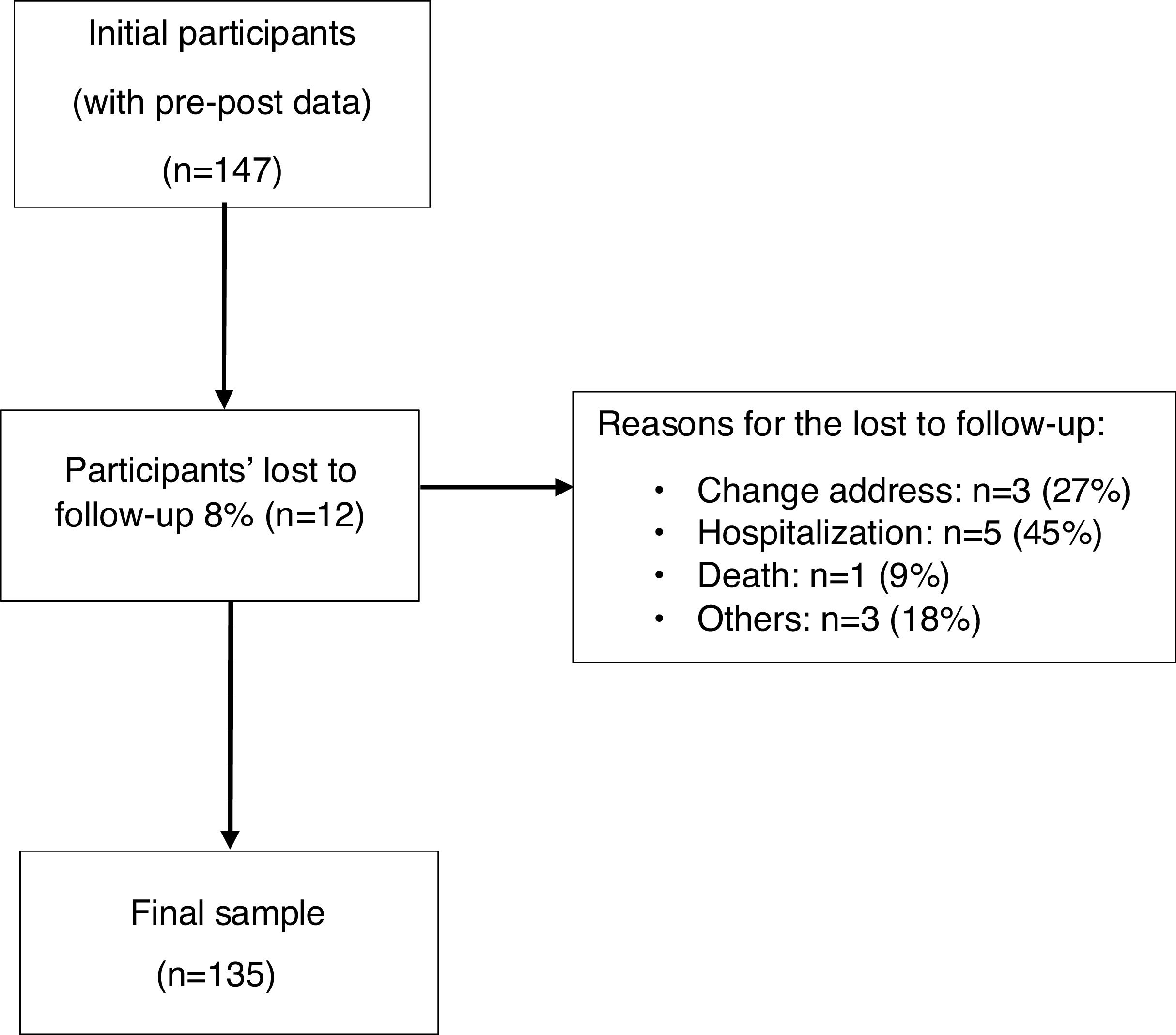

Sample and data collectionTrained interviewers administered a face-to-face questionnaire to participants before entering the programme and after six months, during which time at least four outings were performed. From a total of 147 initial participants, an 8% were lost to follow up; thus 135 participants answered both questionnaires. Reasons for lost to follow-up were change of address, hospitalisation or death.

Since it was a community programme which the main aim was improving health in disadvantaged populations, all people who met the criteria and who wished to participate were included, and no sample size was calculated in the design of the intervention. However, to ensure the validity of the results, we estimated the sample size necessary to detect a change in health perception of 20% (based on the intervention pilot study)17: accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of less than 0.2 in a two-sided contrast, we obtained that the minimum sample size required would be 100 people.18

Study variablesThe explanatory variables were divided into (a) individual characteristics: sex, age, time (in months) without leaving home, and educational level and (b) intervention dose estimated through the number of outings. The dependent variables were self-rated health, mental health, and quality of life. Self-rated health was assessed through the question ‘How do you assess your health in general?’ with a five categories Likert scale, which was dichotomised into good (fair, good and very good) or poor (poor or very poor).19 Mental health was assessed using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), which is made up of 12 items that are answered using a 4-point Likert (0–4) scale. We analysed the GHQ-12 as a dichotomous variable where people with three or more positive answers were considered to be at risk of poor mental health,20 and also as a continuous variable, that is the sum of all the items (ranging from 0 to 36), where high values denote high mental disorder.21 The Likert scoring of the GHQ yielded a normal distribution and we have used this variable as a continuous variable in our analysis. Quality of life related to health was evaluated using the EuroQol scale (EQ-5D-3L),22 which assesses five dimensions including mobility, personal care, daily activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety/depression. EQ-5D-3L has three levels of severity in each item, and it was dichotomised into: (a) ‘no problems’ or ‘some problems’ and (b) ‘severe problems’.23 User's satisfaction with the programme was evaluated through a set of questions used in Barcelona Health in the Neighbourhoods interventions to assess general satisfaction, dimensions of frequency, duration, time, place and punctuality and whether the participants would recommend it to other people.24,25

Data analysisWe performed a univariate analysis to describe individual characteristics and intervention dose and a bivariate analysis to assess changes in self-rated health, mental health and the five quality of life dimensions, within the explanatory variables, before and after the intervention through McNemar tests for paired data. Then, we fitted generalised estimating equation regression models for the outcome variables adjusting for explanatory variables. Poisson regression models were fitted for self-rated health and quality of life, and mental health was analysed through its continuous variable with a linear model. We analysed each quality of life dimension separately, as we did not expect that the programme would affect all of them.

In our study there were two types of missing data: losses to follow up and items missing within the survey. To deal with the first type we compared the socio-demographic characteristics of lost cases with the total number of participants (t-test for continuous variables and chi2 square test for categorical variables). For the missing data in the specific items in the GHQ-12 scale, we applied the simple imputation method based on the person-mean score when less than two items were missing per case. This method is considered to be adequate due to the high proportion of complete cases.26 All analyses were conducted using the statistical package STATA.

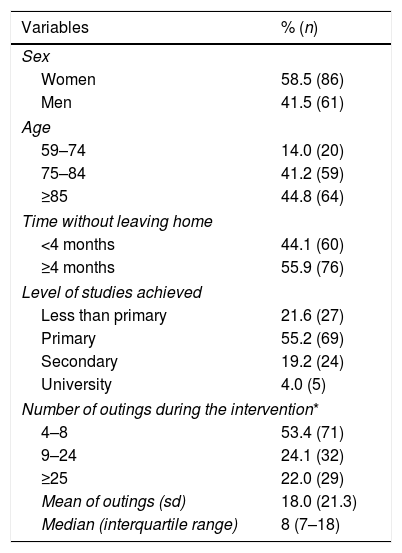

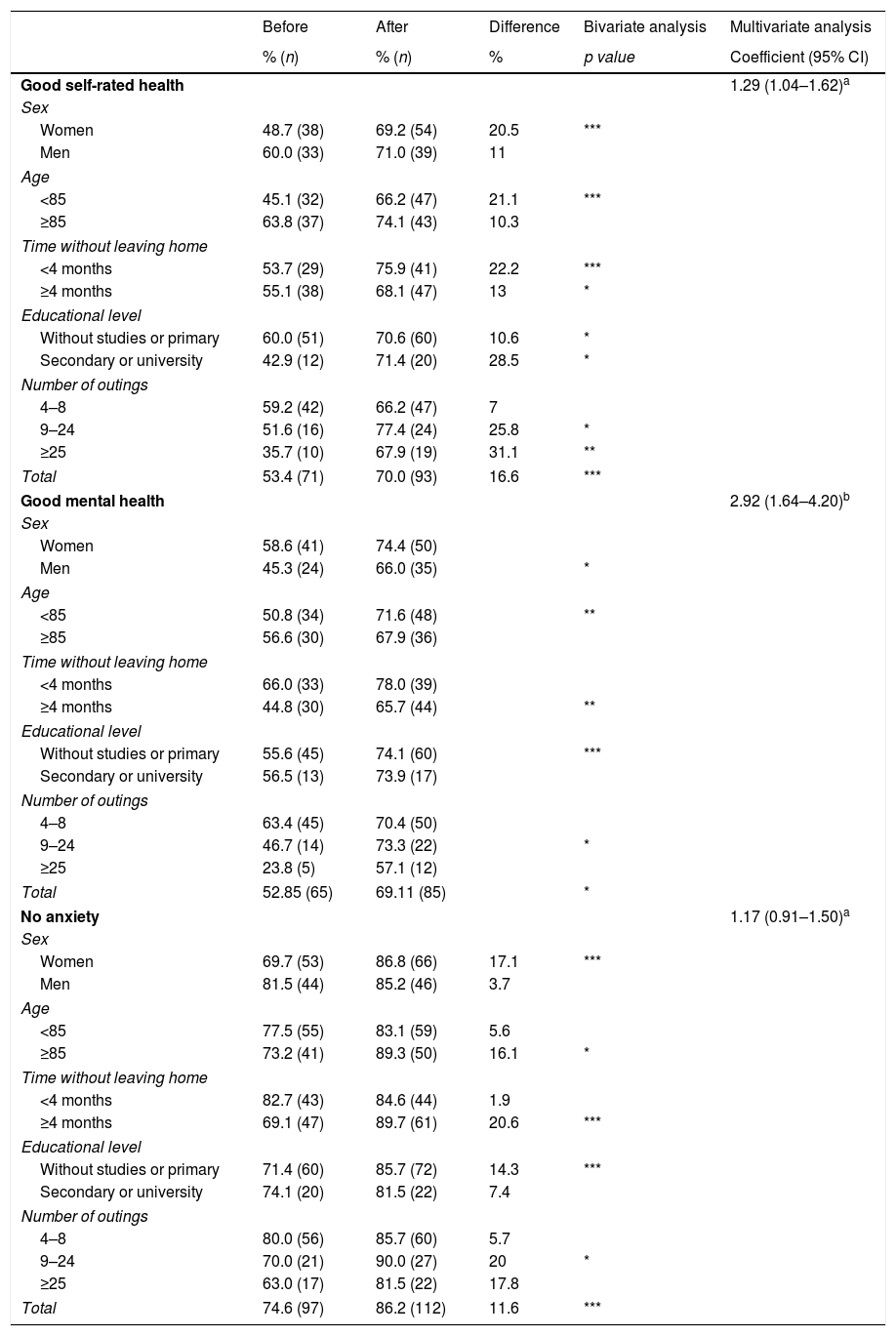

ResultsThe study sample was consisted mainly of women (58.5%), people aged ≥85 (44.8%) and had not left their homes for ≥4 months (55.9%) (Table 2). No differences were observed between follow-up losses and study participants by sex, age and time without leaving home; however, the level of study in the former group was lower than the overall sample. Participants made a median of 8 and a mean of 18 outings during the six months period of study. After the intervention, participants’ self-rated health improved significantly in all categories of the explanatory variables, except for men or for people aged ≥85 years (Table 3). Among participants who made 9–24 outings, good self-rated health increased from 51.6% before the intervention to 77.4% after; among participants who made ≥25 outings, it increased from 35.7% to 67.9%. Self-perceived mental health improved among all participants, especially among men (45.3% to 66.0%), those younger than 85 years old (50.8% to 71.6%), those who had not left their homes for ≥4 months (44.8% to 65.7%), those who had made 9–24 outings (46.7% to 73.3%), and those with a lower level of education (55.6% to 74.1%). The intervention had a positive effect on anxiety, with significant increases of people reporting no anxiety among women (69.7% to 86.8%), people aged ≥85 (73.2% to 89.3%), those who had not left their homes for ≥4 months (69.1% to 89.7%), those who had made 9–24 outings (70.0% to 90.0%), and those with a lower level of education (71.4% to 85.7%). We did not observe significant changes in other aspects of quality of life (mobility, personal care, daily activities and pain or discomfort).

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants from 2010 to 2015.

| Variables | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Women | 58.5 (86) |

| Men | 41.5 (61) |

| Age | |

| 59–74 | 14.0 (20) |

| 75–84 | 41.2 (59) |

| ≥85 | 44.8 (64) |

| Time without leaving home | |

| <4 months | 44.1 (60) |

| ≥4 months | 55.9 (76) |

| Level of studies achieved | |

| Less than primary | 21.6 (27) |

| Primary | 55.2 (69) |

| Secondary | 19.2 (24) |

| University | 4.0 (5) |

| Number of outings during the intervention* | |

| 4–8 | 53.4 (71) |

| 9–24 | 24.1 (32) |

| ≥25 | 22.0 (29) |

| Mean of outings (sd) | 18.0 (21.3) |

| Median (interquartile range) | 8 (7–18) |

Self-rated health, mental health and anxiety prevalence among isolated elder participants before and after the programme (n=135).

| Before | After | Difference | Bivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % | p value | Coefficient (95% CI) | |

| Good self-rated health | 1.29 (1.04–1.62)a | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 48.7 (38) | 69.2 (54) | 20.5 | *** | |

| Men | 60.0 (33) | 71.0 (39) | 11 | ||

| Age | |||||

| <85 | 45.1 (32) | 66.2 (47) | 21.1 | *** | |

| ≥85 | 63.8 (37) | 74.1 (43) | 10.3 | ||

| Time without leaving home | |||||

| <4 months | 53.7 (29) | 75.9 (41) | 22.2 | *** | |

| ≥4 months | 55.1 (38) | 68.1 (47) | 13 | * | |

| Educational level | |||||

| Without studies or primary | 60.0 (51) | 70.6 (60) | 10.6 | * | |

| Secondary or university | 42.9 (12) | 71.4 (20) | 28.5 | * | |

| Number of outings | |||||

| 4–8 | 59.2 (42) | 66.2 (47) | 7 | ||

| 9–24 | 51.6 (16) | 77.4 (24) | 25.8 | * | |

| ≥25 | 35.7 (10) | 67.9 (19) | 31.1 | ** | |

| Total | 53.4 (71) | 70.0 (93) | 16.6 | *** | |

| Good mental health | 2.92 (1.64–4.20)b | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 58.6 (41) | 74.4 (50) | |||

| Men | 45.3 (24) | 66.0 (35) | * | ||

| Age | |||||

| <85 | 50.8 (34) | 71.6 (48) | ** | ||

| ≥85 | 56.6 (30) | 67.9 (36) | |||

| Time without leaving home | |||||

| <4 months | 66.0 (33) | 78.0 (39) | |||

| ≥4 months | 44.8 (30) | 65.7 (44) | ** | ||

| Educational level | |||||

| Without studies or primary | 55.6 (45) | 74.1 (60) | *** | ||

| Secondary or university | 56.5 (13) | 73.9 (17) | |||

| Number of outings | |||||

| 4–8 | 63.4 (45) | 70.4 (50) | |||

| 9–24 | 46.7 (14) | 73.3 (22) | * | ||

| ≥25 | 23.8 (5) | 57.1 (12) | |||

| Total | 52.85 (65) | 69.11 (85) | * | ||

| No anxiety | 1.17 (0.91–1.50)a | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 69.7 (53) | 86.8 (66) | 17.1 | *** | |

| Men | 81.5 (44) | 85.2 (46) | 3.7 | ||

| Age | |||||

| <85 | 77.5 (55) | 83.1 (59) | 5.6 | ||

| ≥85 | 73.2 (41) | 89.3 (50) | 16.1 | * | |

| Time without leaving home | |||||

| <4 months | 82.7 (43) | 84.6 (44) | 1.9 | ||

| ≥4 months | 69.1 (47) | 89.7 (61) | 20.6 | *** | |

| Educational level | |||||

| Without studies or primary | 71.4 (60) | 85.7 (72) | 14.3 | *** | |

| Secondary or university | 74.1 (20) | 81.5 (22) | 7.4 | ||

| Number of outings | |||||

| 4–8 | 80.0 (56) | 85.7 (60) | 5.7 | ||

| 9–24 | 70.0 (21) | 90.0 (27) | 20 | * | |

| ≥25 | 63.0 (17) | 81.5 (22) | 17.8 | ||

| Total | 74.6 (97) | 86.2 (112) | 11.6 | *** | |

After adjusting for explanatory variables, the multivariate analysis showed that the improvement, before and after the intervention, in self-rated health (aRR 1.29; (CI) 95%: 1.04–1.62) and mental health (β: 2.92; (CI) 95%: 1.64–4.20) remained significant, while no differences were found in anxiety (aRR 1.17; (CI) 95%: 0.91–1.50).

Participants reported being very satisfied with the programme, with an average score of 9.3 out of 10 and 99% declared they would recommend the programme to other people. Dimensions of satisfaction, such as frequency, duration, time, place, and punctuality, were rated as adequate by almost 100% of the participants, although the frequency of the group outings was considered insufficient (data not shown).

DiscussionThis study shows that this community health intervention improves participants’ self-rated health and mental health and reduces anxiety. We observed significant improvements in self-rated health in all sociodemographic groups, except for men. The number of outings was also associated with good self-rated health. There was a general improvement in mental health and lower rates of anxiety, mainly among men, people who had not left their home for a long time, those with a lower level of education, and those who had made more than 9 outings during the intervention. The improvements in self-rated health and mental health remained significant with the adjusted analysis.

Evidence shows that people from vulnerable groups are the least able to positively respond to population-approach interventions.27 In this sense, this community health intervention, which forms part of a strategy to reduce social health inequalities in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, seems to have contributed to alleviating inequalities by benefiting people with more cumulative risk factors (those with a lower level of education and ≥4 months without leaving home).

This intervention is one of the few, at the individual level, that seems to be effective in reducing social isolation and loneliness. Previous studies have shown that the most effective individual interventions to reduce elder people loneliness are those that use new technologies to increase socialisation with loved ones or new friendships.28–31 Other types of individual intervention, such as home visits, have shown to be ineffective in reducing loneliness among older people,3,31 probably due to the relatively small increase in their social interaction, and that they do not encourage participants to leave their homes. A number of group-based interventions, such as educational or volunteering activities over several months, have proven to be effective in reducing loneliness among elderly people, by generating purpose in their lives, promoting social participation and support, and reducing stigma.3,8,9,31–34 There is also evidence describing that community health interventions can contribute to improved health, wellbeing and social support in disadvantaged populations.35–38 One systematic review found that 21 out of 24 studies analysed reported improvements in health-related behaviours, a range of health outcomes, health literacy and the use of health services, as well as community changes such as empowerment or public health planning. In addition, 60% of the studies included reported reduced health inequalities.35

Furthermore, evidence indicates that effective interventions are not restricted to group interventions or solitary interventions.29,39,40 Our intervention combined individual and group outings, to promote social support and participation, and this could be another key component of the intervention's success.

Our intervention was implemented at the time when the Catalonian Department of Health launched COMSALUT programme, with the objective of redirect the Primary Health Care towards health promotion and community health, as well as tackling social health inequalities. This context may have enabled synergies and exchanges between Primary Health Care, Public Health and other community agents to boost local community health.41

One of the main strengths of this intervention is the community response to a global health problem among older people, especially among those with fewer resources.4,9 This community health intervention is based on the information that Primary Health Care, Social Services, and other community agents collect on a daily basis, to access a group of the population that can hardly benefit from usual community interventions. This intersectoral and communitarian approach strengthens community health and the co-production of interventions to reduce social inequalities. Another strength of this study is that it is one of the first community health interventions that evaluates health outcomes measured with validated scales.

The main limitation of this study is the absence of a comparison group. An experimental design was not feasible due to ethical constraints (leaving one of the study arms at home for 6 months) and the limited number of eligible participants. Another limitation could be reverse causation between the number of outings and self-reported health, i.e. participants who had good health may have been more likely to have more outings, while those with poorer health may have been unable to leave their homes for this reason. Even though, some elements may reinforce and give support to our results: (a) a pilot test of the intervention yielded similar results in self-rated health, mental health and anxiety reduction17; (b) a strong positive relationship between the number of outings and health outcomes; (c) the improvements in variables expected to suffer a maturation bias, as older people's self-rated and mental health tend to worsen over time, and (d) the great satisfaction reported by the participants.

We conclude that community health strategies based on periodic outings to promote social relationships and social participation could contribute to improve self-rated health and alleviate mental health risks among vulnerable elderly people isolated at home due to mobility limitations and architectural barriers. Replications of this community health intervention could work in similar contexts.

- •

Social isolation among the elderly is associated with increased mortality, poorer self-rated health, lower quality of life and greater risk of dementia.

- •

Evidence has shown that interventions to promote social participation for older people can prevent loneliness and social isolation associated among the least wealthy groups.

- •

Architectural barriers can hinder or prevent people from going out on their own and have been associated with the perception of loneliness. In Barcelona, 31.6% of buildings did not have an elevator, and this percentage was higher in the most deprived neighbourhoods.

- •

This community health intervention is a response to a global health problem among older people, especially among the most vulnerable groups.

- •

This intervention based in periodic outings to promote social relationships and social participation could contribute to improve self-rated health and alleviate mental health risks among the most vulnerable elderly people isolated at home.

- •

This community health intervention has enabled synergies and exchanges between primary health care, public health, and other community agents to boost local community health.

Obtained (2019/8569/I) (undisclosed details to protect anonymity).

Informed consentA written informed consent for participation was signed by each participant before intervention.

FundingUndisclosed details to protect anonymity.

Conflict of interestsNone declared.

The authors are most grateful to people who participated in the study and generously shared their time. We thank Michael Maher and Gavin Lucas for their help in correcting the English version of this article. This article forms part of the doctoral dissertation of Ferran Daban Aguilar at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra of Barcelona.