Los niños y niñas tienen derecho a la salud y a disfrutar su niñez de la mejor forma posible. Esta revisión tiene como objetivos mostrar los principios de la salud pública aplicables a la práctica pediátrica, describir los cambios demográficos y epidemiológicos en la niñez mexicana y el papel de los principales determinantes de la salud y de las herramientas modernas de la salud pública para este grupo de edad.

El análisis de la información demográfica y epidemiológica disponible muestra la reducción de la mortalidad neonatal, infantil y, en el menor de un año, la prevalencia creciente de enfermedades crónicas y la persistencia de padecimientos infecciosos y nutricionales. Se describe la influencia de los determinantes sociales de la salud y las herramientas de salud pública, que consisten en la medición de necesidades y del estado de salud, la capacitación del personal, el diseño e implementación de mediciones del desempeño y el desarrollo de investigación multidisciplinaria.

Se concluye que es indispensable tratar de mantener un paralelismo entre la dinámica demográfica y epidemiológica de este grupo de edad, sus necesidades de salud y la oferta de servicios de salud pública, con lo cual se puede contribuir a mejorar el estado de salud en los niños y mejorar sus probabilidades de crecer, desarrollarse y aprender, para que puedan convertirse en adultos sanos y productivos.

Children have the right to health and to enjoy their childhood in the best possible way. This paper aims to show the principles of public health that are applicable to pediatric practice. It describes demographic and epidemiological changes happening in Mexican children, the influence of social determinants of health and the modern tools of public health for this age group.

Analysis of demographic and epidemiological information shows the reduction of neonatal and infant mortality, the increasing prevalence of chronic disease and the persistence of infectious and nutritional diseases. The influence of social determinants of health are described, and the public health tools that consist of measuring needs and health status, staff training, design and implementation of performance measures and development of multidisciplinary research were addressed.

We conclude that it is essential for public health services to keep pace with the demographic and epidemiological dynamics and health needs of this age group. Improvement of the health status of children increases their chances to grow, develop and learn in order to become healthy and productive adults.

1. Introduction

Children have the right to health and to enjoy their childhood in the best way possible.1 Healthy children have better opportunities to grow, develop and learn and to then become healthy and productive adults.2 Public health practices contribute to achieve these aspirations. Public health actions are performed according to the stage of development. Its effects on health are immediate as well as during later ages.

In Mexico, inequality of conditions of the population requires that public health fulfills two roles: reducing disparities and improving the health of children and adolescents. This paper presents the principles of public health applicable to pediatric practice, describes the demographic and epidemiological changes occurring in Mexican children, addresses the role of the main determinants of health, and presents modern tools of public health for this age group.

2. Definitions of health and public health in childhood

The definition of childhood health is as follows: "health is the extent to which children, individually or collectively, are able to or prepare to develop themselves and realize their potential, meet their needs and expand their capacity in order to interact successfully with the biological, physical and social environment."

The notion of health status during childhood, defined as the period between 0 and 18 years old, is different from the state of health during adulthood. Children, because of their development, have a constant dynamic in their health and are longitudinally exposed to multiple influences of biological, environmental, cultural and behavioral character. These influences can become risk factors or protective and/ or promoters of health.3

The conceptual and empirical development of the field of public health focused on childhood is evolving. Blair et al.4 proposed the following definition of public health for this age group: "art and science of promoting and protecting health and wellness, and preventing disease in infants, children and adolescents, using the skills and organized efforts of the health personnel, public institutions, civil society groups and society." To achieve its mission, the actions are based on the knowledge of the health and disease patterns, identifying risk factors and strategies to mitigate its effect and to improve the health and well-being of children and adolescents.

3. Public health objectives aimed at children and adolescents

The pediatric population has specific characteristics and health needs that require specific responses in public health; therefore, it is essential to generate further evidence and knowledge to the analysis and implementation of solutions at the population level of the health problems that affect this age group.

Identifying the issues that affect health and development involve the knowledge of different fields such as demographics, the influence of socioeconomic status and inequality, social and family cohesion, migration, marginalization, mental health, quality of life, wellness, lifestyle, the effect of policies that promote health, nutrition and physical growth, development (intellectual and social), vital statistics, injury, environment and access and use of services.5 These areas are dynamic and it is critical to identify and measure their influence on health status and to identify and quantify the necessary elements to determine the magnitude of the needs in the pediatric population and the best practices for meeting these needs.

The Committee on Evaluation of Children's Health: Measures of Risk, Protective, and Promotional Factors for Assessing Child Health in the Community proposes five guiding principles:

1. Children are a vital part of society

2. Fundamental differences exist between children and adults, which should motivate special attention to children's health

3. Health during childhood has long-term effects that can manifest in adulthood

4. Manifestations and interpretations of health vary among different communities and among different cultures

5. Epidemiological data of child health and its determinants are needed to design services that allow to maximize health status during childhood and consequently in adulthood

4. Demographic and epidemiological aspects

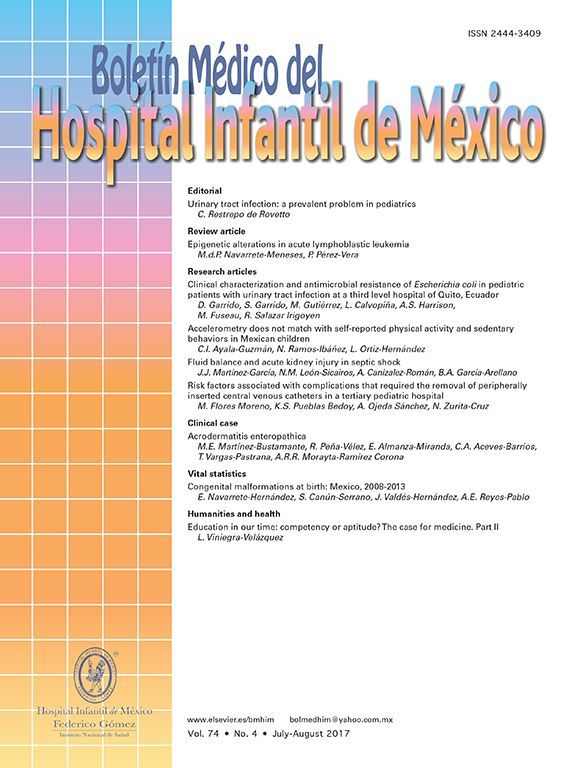

The demographic and epidemiological profile of children and adolescents has changed in a very short period. Between 1950 and 1970, the group of children 0- to 20-years-old increased until it represented 57% of the total population. Afterwards, family planning policies and socioeconomic changes in the country helped to maintain a progressive decline in the rate of fertility. Currently, the group of 0- to 20-years-old represents 38% of the population (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Changes between 1950 and 2010 of the proportion of 5-year age groups from 0 to 20 years with respect to the total population (millions). Source: Based on data from INEGI. Population and Housing Census, 1950-1970, 1990, 2000 and 2010. INEGI. Tallies of Population and Housing; 1995 and 2005.

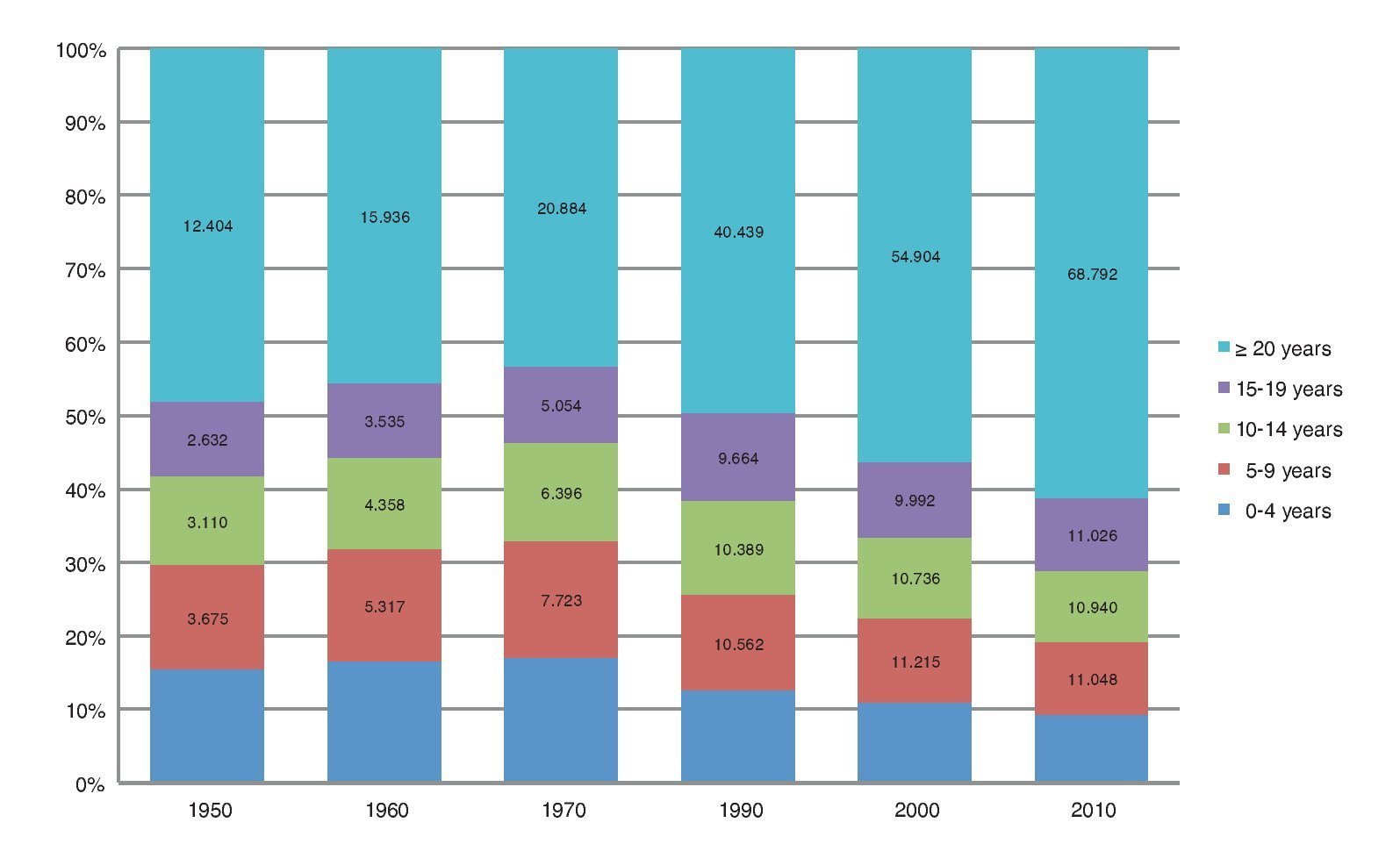

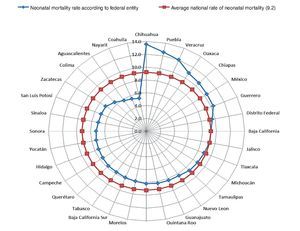

Neonatal, infant and preschool mortality rates have decreased in part by improvements in health conditions and access to health services but still do not reach the figures set for the Millennium Development Goals. Between 1980 and 2009, neonatal mortality was reduced from 15.7 to 9.2/1,000 newborns. Half of neonatal deaths are preventable and occur during labor, delivery and within the first 24 h of life. The main causes of neonatal mortality are prematurity (28%), infections (26%), asphyxia (23%) and congenital malformations (8%). Neonatal mortality rates are not equal in all regions of the country, indicating disparities (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Neonatal mortality rates according to federal district in Mexico (2009). Evaluation of neonatal mortality in neonates affiliated with the Social Protection System in Health. Hospital Infantil de Mexico Federico Gomez; 2009.

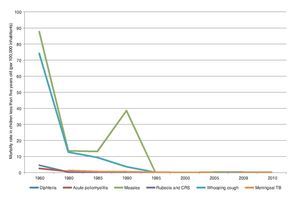

Between 1990 and 2010, the infant mortality rate was reduced from 38 to 14/1,000 live births6 and between 1970 and 2010 the mortality rate among children <5 years old decreased from 109 to 17/1,000 live births. Mortality attributable to preventable diseases has declined significantly due to improvements in sanitation, access to health services and expansion of prevention programs. Figure 3 illustrates the decline in mortality from diphtheria, acute poliomyelitis, measles, rubella, pertussis and meningeal tuberculosis.

Figure 3. Mortality according to preventable diseases by vaccination (Mexico 1960-2010). CRS: Congenital rubella syndrome. Source: Based on data published in Epidemiologic Profile of Vaccine Preventable Diseases in Mexico. Ministry of Health; 2012.

The change in the demographic composition has effects on the population of 0- to 20-years-old both in terms of health status and social capital. Better access and conditions of delivery care have reduced neonatal and infant mortality but have also contributed to a greater number of surviving children whose health is more vulnerable due to various risk factors. This is reflected in an increasing number of children and adults with chronic diseases who require long-term care and for which the social and economic cost is high. Fertility decline is also reflected in the possibility of a greater transfer of resources, both family and public, to children, which has been associated with a better investment in health and education. In population terms, this means that, proportionately, children have greater opportunity to receive more resources per capita, which would be diluted without the decline in fertility.

The epidemiological situation of Mexican children and adolescents reflects complex health needs. In Mexico, the double burden of disease is also seen in childhood. An increasing number of children suffer from chronic diseases among the emerging issues that reflect the interaction with the environment, behavior and genetics. The growing proportion of children with overweight, diabetes, cancer and asthma is evident, along with other problems such as accidental injuries, attention-deficit syndrome and developmental problems.

In some regions of the country, reports of a high prevalence of malnutrition and anemia continue, among other ailments. Malnourished children have impaired cognitive and physical development and lower resistance to disease.7,8 Improving nutritional status is an unresolved problem and presents many challenges. In 2009, the National Assessment Survey of Health Insurance for a New Generation directed to children <2 years old reported that 75% of children had normal weight.

The major deficit was short stature, especially in children living in rural communities (16 and 13%, respectively), and the prevalence of emaciation was 3.8% with a prevalence of obesity of 6.3% also observed.9 In children of this age, the importance of maintaining a nutritional status within acceptable parameters is clearly identified due to its effect on growth and development in later ages.

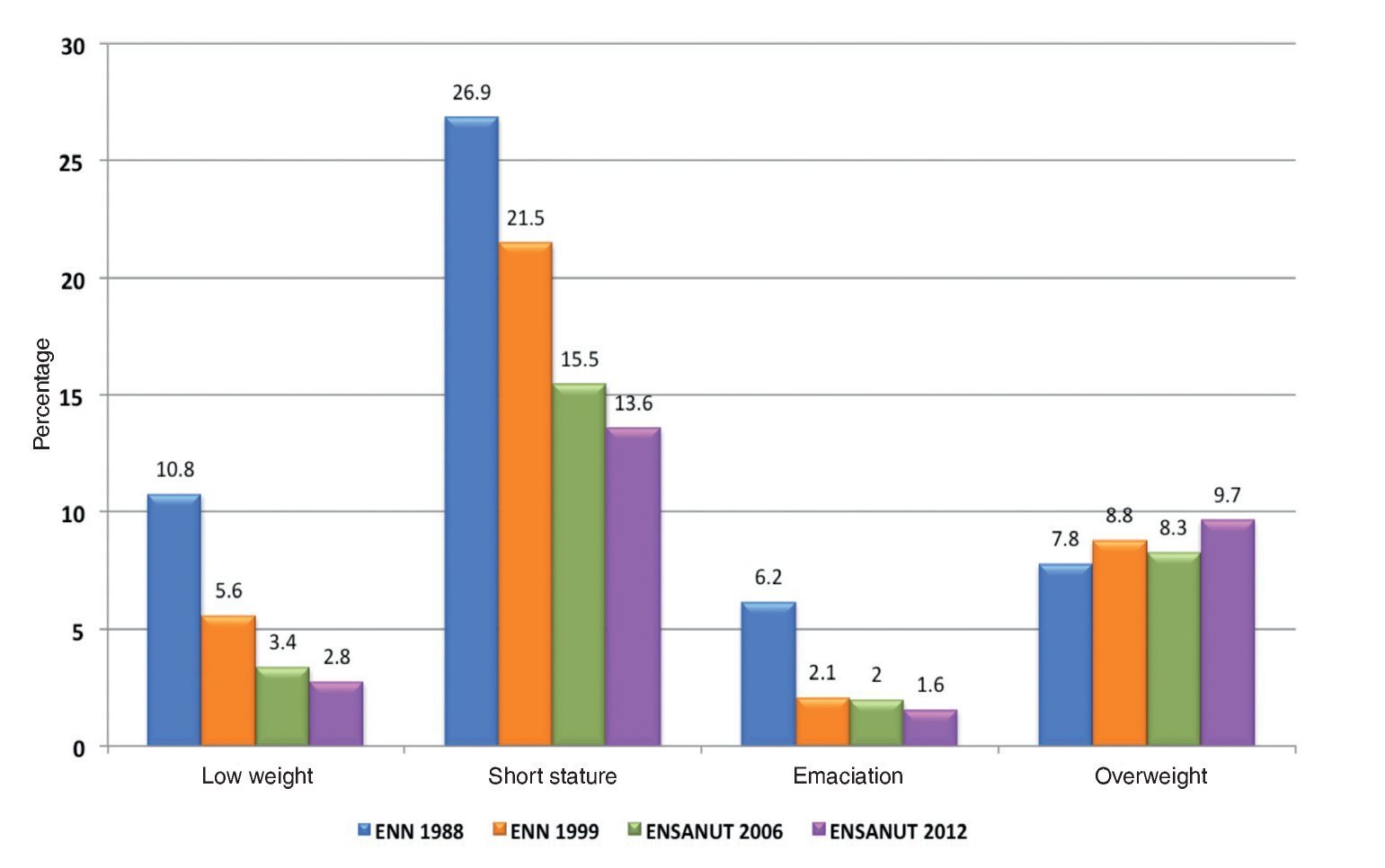

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2012 (ENSANUT) reported a comparative analysis of the national prevalence of underweight, stunting, emaciation and overweight in children <5 years in the national surveys conducted in 1988, 1999, 2006 and 2012.10 Figure 4 illustrates the change in nutritional status in this age group. The progressive reduction of underweight, stunting and emaciation is noteworthy, but the growing problem of overweight is visible, whose proportion has increased from 7.8 to 9.7% in a short period.

Figure 4. Changes in the nutritional status of children <5 years of age between 1998 and 2012. ENN: National Nutrition Survey; ENSANUT: National Nutrition and Health Survey.

Anemia is a nutritional alteration due mainly to iron deficiency and a diet high in phytates. Children with anemia suffer from underdevelopment in cognitive, language and motor abilities as well as demonstrating poor school performance. In addition, their immune response is lower.11,12

The prevalence of anemia is slowly decreasing, but a high percentage of the population continues to suffer from this condition. WHO provides simple performance criteria of anemia prevention programs. Less than 5% of subjects with anemia indicate proper performance, 5% to 19.9% indicate mild problems, 20% to 39.9% moderate problems and more than 40% demonstrate severe problems.13 ENSANUT 2012 reported a national prevalence of anemia of 23.3% (95% CI 21.8-24.8) in preschool children and the highest prevalence was observed in the group aged from 12-23 months (38%, 95% CI 34.9-41.8). It is clear that Mexico still has a problem that ranges from moderate to severe.

In children and adolescents, the problem of chronic diseases is increasing and requires more attention through specific policies and actions. The prevalence of overweight and obesity, diabetes, asthma and cancer are increasing.

Between 1975 and 2000, the incidence of cancer in childhood has increased to alarming levels. Pediatric cancer represents 5% of all oncological diseases and it is the second cause of death, after accidents, in the 5- to 18-year-old age group. Among different ages and between genders, there are differences in the occurrence of some cancers but, in general, the frequency is as follows: acute leukemias rank first followed by central nervous system tumors. In third place are lymphomas and then Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, hepatoblastoma, osteosarcoma, retinoblastoma and Langerhans cell histiocytosis appear. Mexico has substantially invested in funding for the care of these types of cancer in vulnerable populations and the progress is evident.14 However, there are no informational and prevention campaigns aimed at informing the population about how to mitigate risk factors, as well as there being no guidance for health care workers for early identification.

5. Social determinants of health

In the last two decades the notion of the influence of the determinants of health and its ecological nature has become increasingly important due to its interconnection with the biological, behavioral, physical, and socioenvironmental domains. There are different models of determinants of health15-18 whose understanding has detonated lines of research in different disciplines. Evidence has allowed to determine the magnitude of the risks, understand their distribution in the population and design health policies and oriented strategies to mitigate their effects.19,20

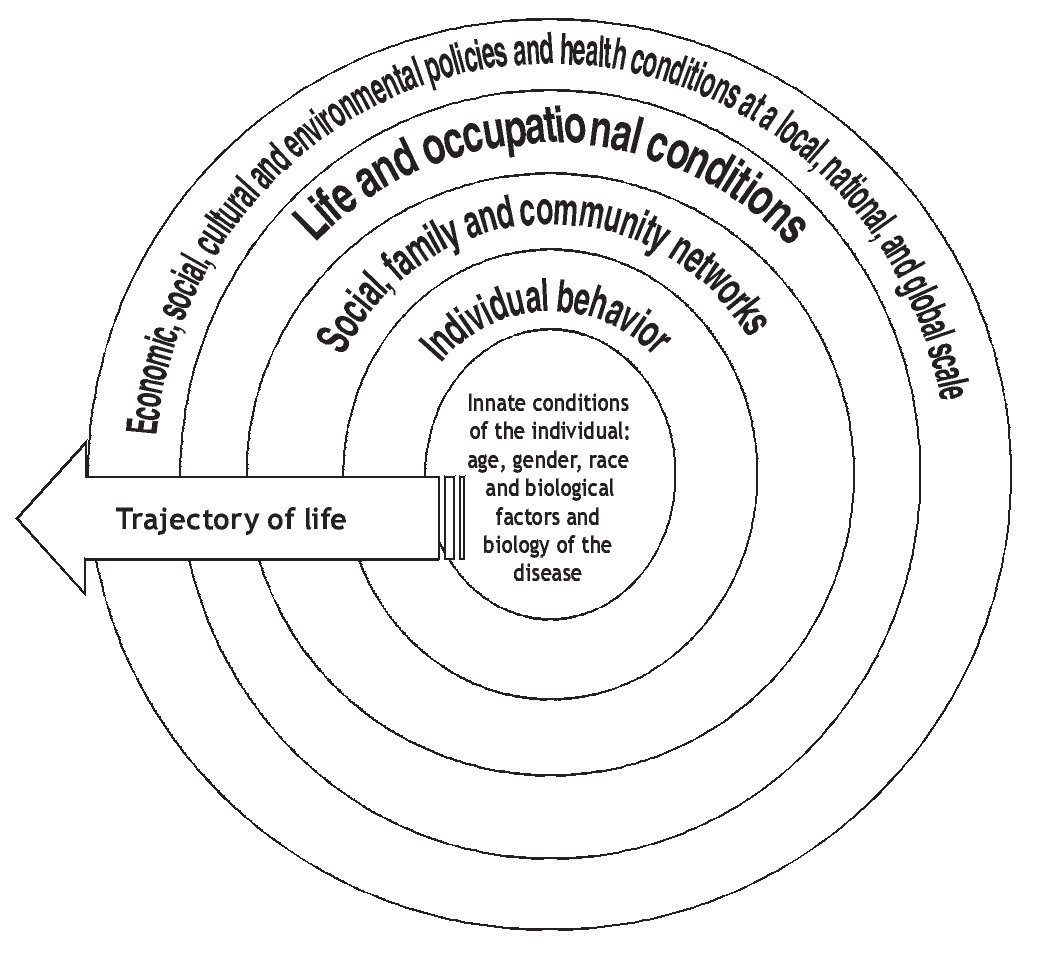

Figure 5 diagrams the determinants of health proposed by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH).21 This diagram is based on the modified model of Dahlgren and Whitehead.22 The diagram is based on the history of life, which indicates that the determinants influence in a dynamic and continuous way during the life of the individual. The starting point is the innate qualities of the person: age, sex, race and biological factors. The next level is the individual behavior, which is determined in the first years of life. The third area is social, family and community networks, which constitute the environment of the individual and have an influence over their health status. The fourth area is living and working conditions, which include psychosocial factors, employment status and occupational factors, socioeconomic status (income, education, and occupation), natural and urban environments, public health services and health services. Finally, the last area corresponds to social conditions— economic inequality, urbanization, mobility, cultural values, attitudes concerning discrimination or tolerance; other conditions include major sociopolitical situations (war, recession, epidemics) and, finally, environment, which includes transportation, water, sanitation, housing conditions and other urban dimensions. The diagram establishes the importance of the multiple determinants of health and intersectorality under which it is possible to understand how health systems must constantly interact with other sectors for the generation and implementation of health policies.

Figure 5. Guidelines of the determinants of health. Source: Modified from the proposal by the Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century, Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. The future of the public's health in the 21st century. National Academies of Sciences. Washington DC. 2003.

Children interact with their environments in ways different from adults. Their body structure and behavior makes them susceptible to environmental influences. In early childhood, the determinants of health have a role that is now increasingly understood.

Wadsworth offers a perspective that comprehensively addresses biological processes during pregnancy and childhood and their interaction with social factors.23 During pregnancy, the nutritional status of the mother is reflected in the nutritional status of the fetus. Malnutrition in pregnancy contributes to the underdevelopment of vital systems, whose effects will manifest in later life, i.e., in learning capacity or under specific conditions. Among the high-risk factors of type 2 diabetes are malnutrition in utero, low birth weight and obesity in adulthood. The consequences of poor development to which exposure to risk factors is added are known as biological programming. This is an adaptive response of the organs and systems that were poorly developed. They perform their function in a limited form and its ability to respond to risk factors is weaker, which affects disease development. Models of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, neurological, renal and respiratory changes have been described in regard to this issue.24,25

Low socioeconomic status is one of the strongest predictors of poor health and development constraints in life. This occurs according to two aspects: the first is material deprivation (e.g,, poor diet, deficient living conditions). The other is psychosocial factors that mediate many of the negative effects that are reflected in neuroendocrine mechanisms of stress response. The members of poor households have higher dropout rates, have more illnesses and malnutrition rates are higher. Consequently they are less likely to find productive employment and improve their income. This cycle is repeated from one generation to the next.26

In the early years, children are completely dependent on their families and communities to meet all their needs. The family context establishes guidelines for the path to adulthood and conditions of family structure and its socioeconomic and cultural conditions have a definite influence on the growth, development, health and educational opportunities of children. A direct relationship has been observed between the increase in the socioeconomic status of the parent and height of the child.27

In Mexico, the program of "Oportunidades" focuses on supporting families to overcome the cycle of poverty. It has been reported that for children enrolled in this program, their height increased 1 cm more than unaffiliated children.28

Shor and Menaghan established a model of a family pathway to children's health.29 The model establishes the interaction between the context of society and family, their characteristics, life cycle and environment which, together with the innate characteristics of the children and their particular development and environment (school, friends), are translated into better health. The improvement in the health of children and adolescents depends on progress in social determinants, family relations, environmental issues and community structure. It is not only the result of medical interventions.

6. Principles and modern tools of public health for children and adolescents

Ten specific principles have been proposed for the practice of public health in children and adolescents:5

1. Monitoring and evaluation of health and well-being

2. Protection and promotion of health and welfare

3. Quality development in a culture of assessment that places evidence into practice and manages risk

4. Management, analysis and interpretation of information, knowledge and statistics

5. Prioritization and professional advice on health and medical care

6. Development and implementation of policies and strategies

7. Collaboration in community development, promoting health and reducing inequality

8. Strategic leadership for health and wellness in the different sectors

9. Education, research and development

10. Management and human capital and physical resources management in an environment of ethics in the practice of public health

Current pubic health tools allow healthcare personnel to have a conceptually coherent outlook of this area, noting that although the majority of those attending the pediatric population tend to focus on personal service. Knowledge of the basics of public health facilitates cooperation and retains the perspective of populational health.

The tools are mainly focused on measurement of needs and health status, training of personnel in modern techniques of public health, design and implemen tation of performance measures in public health and improve ment processes and its consequent assessments, and development of multidisciplinary research in public health.

6.1. Measurement of health status

Measurement of health status and its determinants includes the identification and measurement of risk/protective factors associated with health conditions.30 Actions to determine the state of health include the description of the health status and/or its changes over time or as a result of specific interventions, search and proposal of models explaining differences in levels of health and achievement of the objectives of programs or interventions aimed at improving the necessary training of professionals to assess the health needs of their pediatric population and guiding the actions necessary to meet them.

The most important areas of action to properly measure the health status of children include (i) the definition and framework of health status of children, (ii) improving mechanisms for measuring health status of the children (most of the information comes from national surveys and not from routine health information systems), (iii) promoting the use of information in health status of children for decision making, and (iv) performance measurement.

6.2. The training of health professionals

It is recommended to train health professionals in order that they can understand how changes in behavior, provision of services and innovative interventions can support the improvement of children's health. It is essential that the health care professional knows effective techniques to interact with family and community in order to provide the necessary support to parents to reach their potential as health promoters for their children's health.

6.3. Measuring the performance of public health actions

Performance measurement responds if progress is being made in relation to the established goals, if the appropriate activities are being made to achieve those goals, which areas require attention, and if the actions and achievements can serve as benchmarks for others.31,32

The U.S. Institute of Medicine of identifies three specific functions of public health: measurement, policy development and assurance. Performance evaluation then refers to the structuring of measuring of the achievement of these three specific functions at the local, state or national level.

6.4. Public health research

The areas of research in public health are very broad and range from molecular biology to the study of large populations. Some examples include designing interventions aimed at promoting the potential of development and health for children and adolescents, understanding of the importance and the interactions among the different influences on child health (risk factors and promoters/ protective factors of health), delving into detail about the psychosocial developmental pathways, evaluating exposures of children to contaminated environments and other environmental health risks, proposing measures to reduce health disparities, identifying causal relationships between the levels of development and functional, and status health of children and building pathways for the domains of the determinants of health in children.

The above information is an attempt to present an overview of analysis and development perspectives of public health practices aimed at children and adolescents. Demographic and epidemiological characteristics of this age group are dynamic and it is essential to maintain a correspondence between public health services and health needs that result in constant demand. Investment in public health activities offers the possibility of achieving better health in later life.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Received 13 February 2014;

accepted 14 February 2014

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:rperez@iadb.org (R. Pérez-Cuevas).