Inflammatory pseudotumour is a rare entity, considered benign, and characterised by inflammatory cell mesenchymal proliferation.

Clinical caseThe case is presented 70-year-old man with fever of unknown origin syndrome. He was diagnosed with liver abscesses (one segment IV, adjacent to gallbladder fundus and segment VI), who progressed slowly after antibiotic treatment. In the absence of a diagnosis, although fine needle puncture-aspiration and different imaging tests were performed, elective surgery was decided. The intra-operative histopathology reported the existence of an inflammatory pseudotumour.

ConclusionsInflammatory pseudotumours are clinically classified into different types according to their aetiology, varying therapeutic management based on the same. It is very difficult to diagnose because of the absence of symptoms, blood disorders, or specific radiological findings. Definitive diagnosis often requires histopathological confirmation, in most cases by percutaneous liver puncture, but sometimes exploratory laparotomy or even performing a hepatectomy for confirmation is necessary. The natural history of inflammatory pseudotumour is its regression; thus conservative management may be used through regular checks until resolution, or can be treated with antibiotics, anti-inflammatories and even corticosteroids. Surgical resection is indicated for persistent unresolved systemic symptoms despite medical treatment, in those situations where growth is evident, with or without symptoms, when involving the hepatic hilum, and finally, in case where the possibility of malignancy cannot be ruled out.

El pseudotumor inflamatorio es una entidad poco frecuente, considerada como benigna, caracterizada por la proliferación mesenquimal de células inflamatorias.

Caso clínicoPresentamos el caso clínico de un varón de 70 años con síndrome febril de origen desconocido, diagnosticado de abscesos hepáticos, que tras tratamiento antibiótico no mejoró. Se decidió realizar intervención quirúrgica ante la sospecha de cáncer de vesícula por imágenes de tomografía computada abdominal, reseñando la anatomía patológica intraoperatoria la existencia de un pseudotumor inflamatorio.

ConclusiónEl pseudotumor inflamatorio está clínicamente clasificado en varios tipos según su etiología, variando las opciones de tratamiento en función de la misma. Es muy difícil su diagnóstico debido a la ausencia de síntomas o alteraciones hematológicas o radiológicas específicos. El diagnóstico definitivo requiere a menudo una confirmación histopatológica, en la mayoría de los casos mediante punción percutánea hepática, pero a veces es necesaria una laparotomía exploradora o incluso la realización de una hepatectomía para su confirmación. La historia natural del pseudotumor inflamatorio es su remisión, por lo que se puede llevar a cabo una actitud conservadora mediante controles periódicos hasta su resolución o se puede tratar con antibióticos, antiinflamatorios e incluso corticoides. La resección quirúrgica queda para la persistencia de síntomas sistémicos no resueltos a pesar del tratamiento médico, en aquellas situaciones en las que se evidencia crecimiento, con o sin síntomas, cuando está implicado el hilio hepático y, por último, en caso de no poder descartar la posibilidad de malignidad.

The inflammatory pseudotumour is a very uncommon entity, regarded as benign, characterised by the mesenchymal proliferation of inflammatory cells, mainly lymphocytes, plasma cells and, occasionally, histiocytes.1 It was first observed in the liver in 1953 by Pack and Baker.2 Radiologically, in some cases, this entity may imitate malignant tumours, so its differential diagnosis is highly important.3 It may appear on any part of the organism, the lungs being the most frequent location, although it has also been observed in the central nervous system, the eyes, the liver or the spleen.

This is the clinical case of a 70-year-old male patient with symptoms of low-grade fever and constitutional syndrome which presents 2 liver lesions indicating liver abscesses, as observed with an abdominal computer tomography.

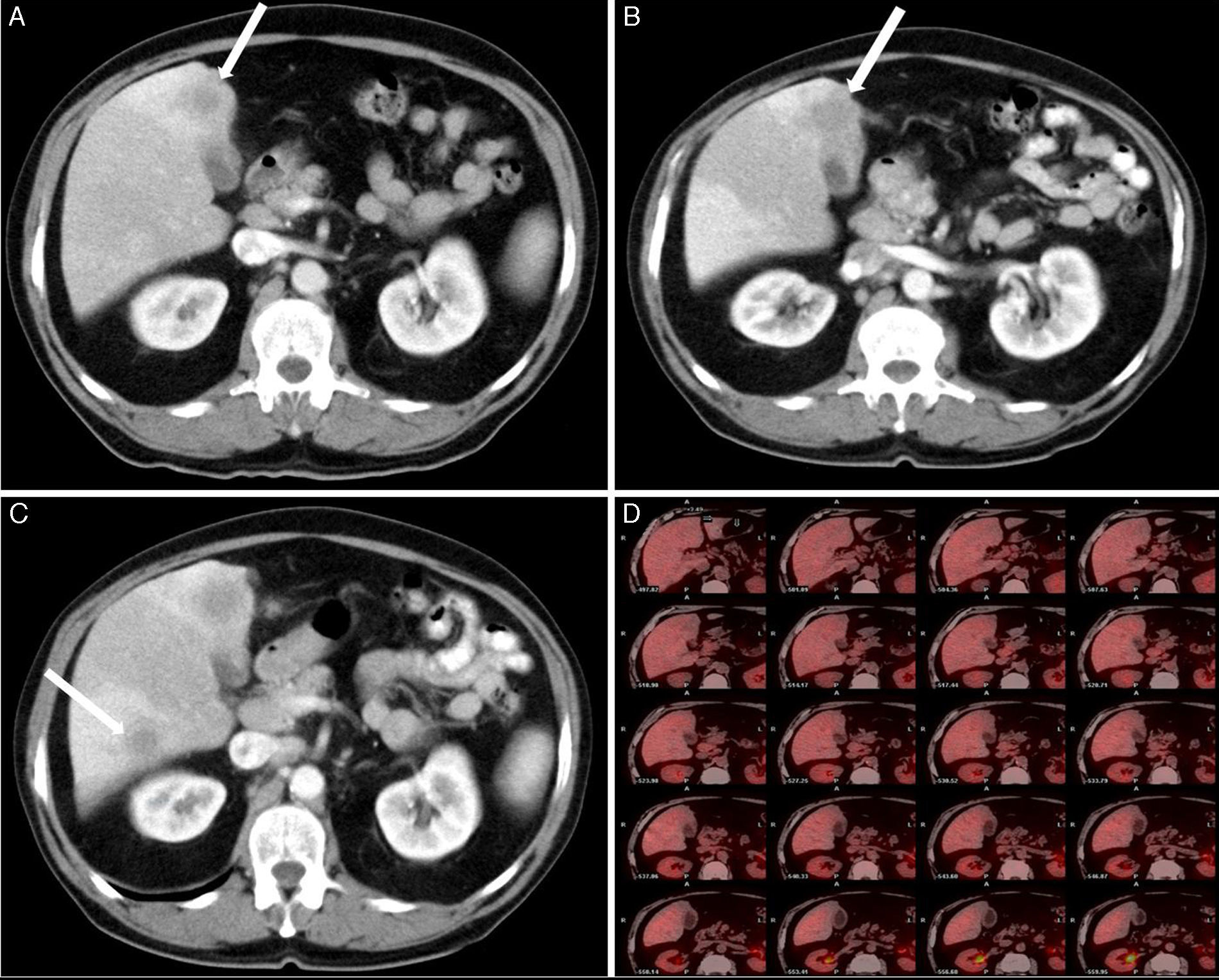

Clinical caseThis is the clinical case of a 70-year-old male patient with a personal history of penicillin allergy, high blood pressure, lung tuberculosis, diabetes, gouty arthritis, renal lithiasis and colon diverticulitis. The patient was admitted to his reference hospital due to clinical symptoms with a progression of at least 3 weeks involving low-grade fever, asthenia, anorexia, weight loss and oligoarthritis (of the knees and interphalangeal joints). The patient was in good general condition and his physical examination was normal. Laboratory tests show the presence of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 153IU/l (8–61), alkaline phosphatase 142IU/l (40–129) and total bilirubin 0.41IU/l (0.05–1.1), with liver lysis enzymes within normal ranges. A test was carried out to rule out the presence of an infectious disease (human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C virus, cytomegalovirus, Coxiella burnetii, lues, Q fever, rose bengal and hydatidosis), which had a negative result, as well as of the presence of an immunological disease (antinuclear antibodies, antibodies extracted from the nucleus, anti-DNA antibodies, anti-endothelial cell antibodies), which also had a negative result. All the tumour markers (alpha-phetoprotein, CEA, CA19-9 and prostatic antigen) were negative. The echocardiography showed no signs of endocarditis. A sputum bacilloscopy and culture were conducted, and a negative result was obtained as well, as it occurred with the urine culture and colonoscopy. A neck–thorax–abdomen computed tomography was carried out, and the only finding was the thickening of the gallbladder walls, with evidence of a poorly-defined hypodense lesion of about 17mm in diameter in segment IV located in the gallbladder bed, which could be related to inflammatory changes, although liver abscess could not be ruled out (Fig. 1A). In an abdominal ultrasound scan, a nodule was observed in segment IV, without thickening of the gallbladder wall. Based on these results, symptoms were treated as liver abscess, and an antibiotic with metronidazole, levofloxacin and aztreonam was administered. After a mild improvement, symptoms reappeared, so a thoracoabdominal computed tomography for control was carried out again 4 months after the diagnosis, and a slight growth of the lesion in segment IV, 25mm was observed, as well as a new growth in segment VI, 16mm, with persistence of diffuse and unspecific thickening of the gallbladder walls (Fig. 1B and C). In the nuclear magnetic resonance imaging, a liver focal lesion of approximately 2cm was observed in segment IV, hypointense in T2 sequences. Adjacently to this lesion, there were 2 nodules of a smaller size and similar appearance (satellite nodules). After the administration of contrast material, these lesions presented a discrete late enhancement. These lesions were surrounded by an alteration in the liver parenchyma which showed a diffuse increase in the intensity of the signal in T2 sequences. In segment VI, there was another nodule of 14mm and similar characteristics, also surrounded by liver parenchyma of diffusely increased signal. In diffusion sequences, nodules showed no restrictions (not related to abscesses, but do indicate metastasis). The gallbladder showed no lithiasis, although it did show thickening of the wall, mainly in the fundus, adjacently to the lesion of segment IV, which ruled out neo-formation. Based on these findings, a puncture-aspiration technique with fine needle was indicated for these lesions, and a non-conclusive result was obtained. A positron emission tomography was conducted using, as tracer, 18-fluorodeoxyglucose, without there being hypermetabolism focuses in the liver (Fig. 1D) or in any other location indicating malignancy. The patient was transferred to our hospital, diagnosed with liver lesions compatible with abnormal-progression liver abscess, without being able to rule out tumour origin, with a non-conclusive result obtained in the puncture-aspiration technique with fine needle. A scheduled surgical intervention was conducted, and the gallbladder showed chronic inflammatory signs with thickened wall and tumour in the bed adjacent to the fundus. The hard lesion was located in the liver area in segment VI, of 11mm in diameter, and it showed a dotted pattern on the liver surface (in segments III, IV and V), similar to the metastatic miliary seeding, as well as on the omentum. An intraoperatory ultrasound scan was conducted, and other intraparenchymal lesions were ruled out. After the analysis of several intraoperatory biopsies of the liver lesions and omental lesions, all of these were reported as lymphoid infiltration without malignancy signs, compatible with an inflammatory pseudotumour. A cholecystectomy was conducted on the gallbladder bed, which included the tumour (Fig. 2).

(A) Abdominal computed tomography: thickening of the gallbladder walls, with evidence of poorly-defined hypodense lesion of 17mm in diameter in segment IV located in the gallbladder bed. (B) Abdominal computed tomography: persistence of diffuse and unspecific thickening of the gallbladder walls, and growth of the lesion in segment IV, 25mm. (C) Abdominal computed tomography: new lesion in segment VI, 16mm. (D) The positron emission tomography showed no hypermetabolic focuses in the liver indicating malignancy.

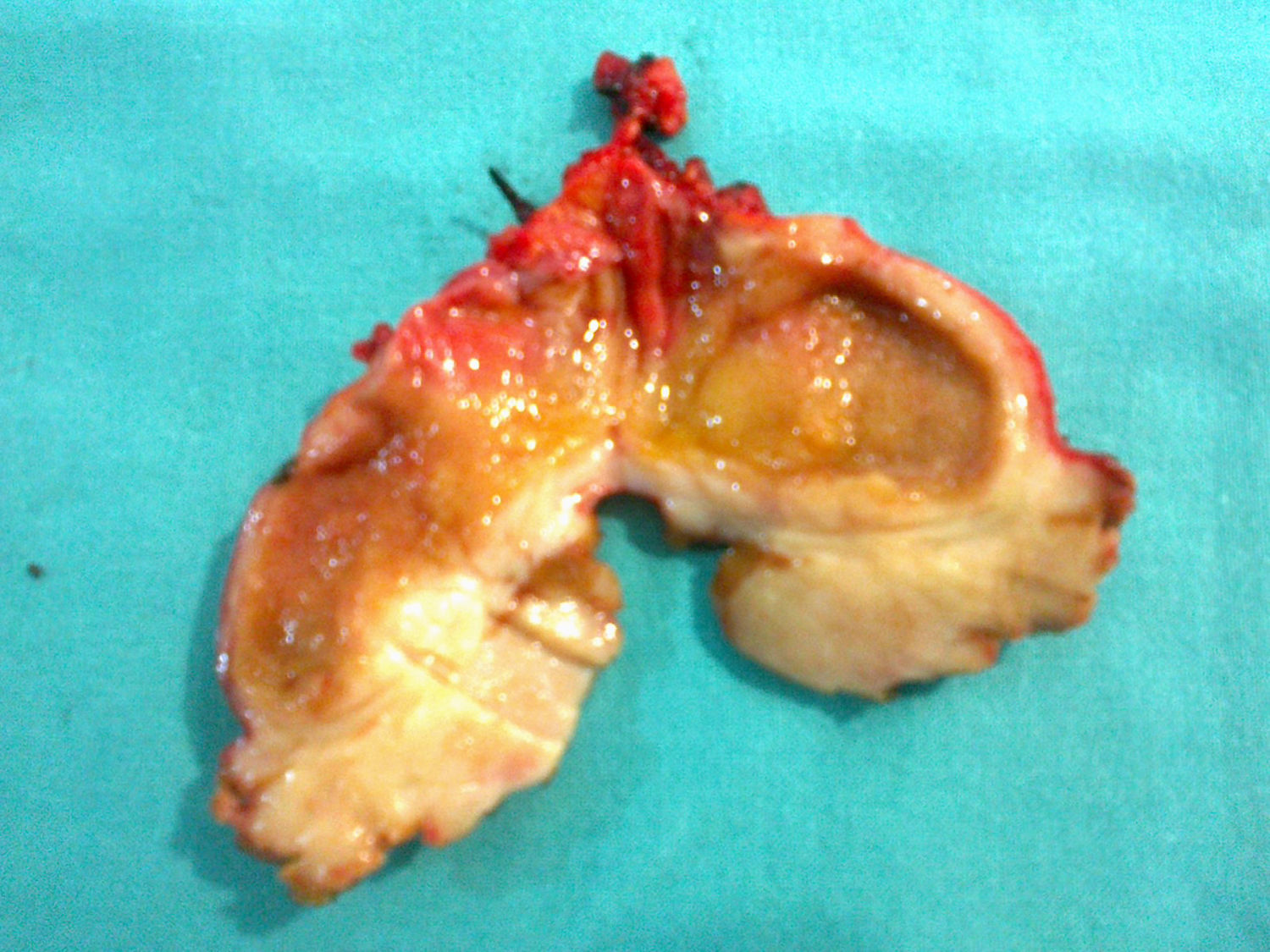

The patient showed good post-operative progression, and was discharged five days after the intervention. The definitive results of the pathological anatomy assessment indicated, on a macroscopic level, the presence of gallbladder with thickened walls and lesions arising from the fundus, without these affecting the mucosa. After the microscopic study, there were histological findings indicating the presence of an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour or inflammatory pseudotumour. The rest of the samples sent reported the presence of liver tissue with a distorted structure as a result of the diffuse fibrosis affecting the liver parenchyma and porta spaces, accompanied by intense mature inflammatory lymphoplasmocytic exudate. Moreover, in the omental sample, fibrous tissue with mature lymphoplasmocytic infiltration was observed. In the immunohistochemical analysis, there were no signs of clonal reorganisation for the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene.

DiscussionThe inflammatory pseudotumour or inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour or plasma cell granuloma is a tumour-forming lesion, with an inflammatory-reparative nature or benign behaviour reactive nature, which is very uncommon and was first observed in the liver by Pack and Baker2 in 1953. It is characterised by the mesenchymal proliferation of inflammatory cells, particularly lymphocytes, plasma cells and, occasionally, histiocytes.1 The physiopathology of the inflammatory pseudotumour is still not very well known, but its inflammatory pathological pattern and systemic symptoms, such as fever and discomfort, demonstrate the existence of an underlying infectious agent, although its presence is not always confirmed. It usually affects children or young adults, particularly male individuals,4 and there seems to be a greater incidence in non-Caucasian races.5,6

The inflammatory pseudotumour is clinically classified into different types based on its aetiology, which leads to different treatment options. Infections and autoimmune disorders are originally the causes of this entity. The inflammatory pseudotumour of infectious origin may be caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, non-tuberculous mycobacteria, Escherichia coli, Gram-positive cocci and Klebsiella pneumoniae. The detection of these microorganisms can confirm the existence of inflammatory pseudotumour, which allows for the diagnosis to be further validated by the response of patients to specific anti-bacterial agents.

It is very difficult for physicians to diagnose this condition given its lack of symptoms, haematological anomalies or specific radiological findings. Clinically, it may present fever, constitutional syndrome, abdominal pain or general discomfort. The laboratory report usually shows an increase in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, leukocytosis, anaemia, hypertransaminasaemia or hypoalbuminaemia.

Histopathologically, it is characterised by the presence of myofibroblasts wrapped in collagen tissue, densely hyalinizated, with inflammatory infiltration and predominance of lymphocytes and polyclonal plasma cells, reparative changes with fibrosis, areas with cellular necrosis and, sometimes, a granulomatous reaction.4

The radiological results for the inflammatory pseudotumour are also unspecific, since the distribution proportion of inflammatory cells and fibrosis depends on the cause and on the current inflammatory phase, so sometimes it may even imitate malignant tumours.3 Therefore, a late enhancement in the computed tomography with contrast material, particularly in the periphery of lesions, is considered to be characteristic of the inflammatory pseudotumour,7 but it may also be compatible with the cholangiocarcinoma or metastatic lesions. In their study, Akatsu et al.8 report that, sometimes, it may present an early capture pattern followed by washout during the late phase of the computed tomography with contrast material, which is typical of the liver carcinoma. However, according to Fukuya et al.,7 most of the times, it shows a variable capture pattern during the portal phase, with a greater enhancement during the late phases, which differs from the liver carcinoma. In the nuclear magnetic resonance imaging, the lesion shows an increase in the intensity of the signal in both T1 and T2 sequences, compared to a normal liver,9 although it may also simulate other malignant conditions. The positron emission tomography uses, as a radio-tracer, 18-fluorodeoxyglucose and it could be helpful, given that, in malignant processes, the capture of this radio-tracer is higher than in inflammatory processes. For instance, it identifies with precision less-differentiated liver carcinomas which require a differential diagnosis regarding the inflammatory pseudotumour.10 However, this differentiation method is limited for the inflammatory pseudotumour, since the capture of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose varies according to the proportion of fibrosis and the infiltration of inflammatory cells. In fact, some studies using positron emission-fluorodeoxyglucose tomography for the inflammatory pseudotumour have shown a high capture of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose,11 comparable to malignancy.

The definitive diagnosis usually requires histopathological confirmation in most of the cases by means of a liver percutaneous puncture, although it may sometimes result in an incorrect diagnosis.12 Therefore, in some cases, especially when malignancy cannot be ruled out, it is necessary to conduct an exploratory laparotomy and even an hepatectomy for its confirmation.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that the inflammatory pseudotumour usually results in remission. Upon confirmation of the diagnosis through a biopsy, a conservative approach may be adopted by conducting regular check-ups until its resolution, or it may be treated with antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs or even corticosteroids.4

Surgical resection, which was originally considered the treatment of choice for these patients, must only be used in certain cases, such as when unresolved systemic symptoms persist in spite of the medical treatment,13 when there is evidence of inflammatory pseudotumour growth with or without symptoms,14 when the hepatic hilum is involved, which could cause gallbladder obstruction and/or portal high blood pressure,15 and, lastly, when the possibility of malignancy may not be ruled out, in spite of the different complementary tests.16

Currently, there are no clinical studies comparing results in patients treated using a conservative approach and those treated with surgery. Furthermore, there is no data regarding the duration of follow-up in patients treated using a conservative approach. More recently, local recurrence and distant metastases have been attributed to lesion ploidy, and aneuploid lesions have a greater chance of recurrence and metastasis than diploid lesions.17 Therefore, the flow cytometry DNA analysis is recommended, so that the clinician obtains diagnostic and prognostic information to individualise the more feasible therapeutic approach.

ConclusionsIn our case, after the patient underwent an extensive study to determine the possible cause of his clinical symptoms, it was decided to conduct a surgical intervention, since his liver lesions could not be identified using a puncture-aspiration technique with fine needle. During the intervention, a lesion in the gallbladder bed closely adhered to the gallbladder fundus was observed. This lesion had lesions compatible with the miliary seeding on the liver surface, as well as on the omentum. Upon the diagnosis of inflammatory pseudotumour, it was decided to conduct an intraoperatory biopsy, a cholecystectomy and the total removal of the lesion from the bed, without resection of the other lesions. Currently, the patient has no symptoms.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Onieva-González FG, Galeano-Díaz F, Matito-Díaz MJ, López-Guerra D, Fernández-Pérez J, Blanco-Fernández G. Pseudotumor inflamatorio hepático. Importancia de la anatomía patológica intraoperatoria. Cir Cir. 2015; 83: 151–155.