Retained surgical items after a surgical procedure is a real, existing, and preventable problem that affects the safety of the surgical patient. Its incidence is not exactly known due to under-reporting of occurrence, due to the potential risk of lawsuits.

Clinical caseA 31 year-old women that had an elective caesarean, apparently without complications. In the immediate post-operative period, clinical features appeared that were compatible with intestinal obstruction, such as inability to channel gas, bloating, abdominal pain and vigorous peristalsis. The diagnosis is made by the recent history of abdominal-pelvic surgery and the finding of a foreign body on a simple X-ray of the abdomen. The patient was operated upon, with a satisfactory outcome, and was discharged 5 days later.

ConclusionA retained surgical instrument is an under-reported event that represents a medical-legal problem, leading to various complications, including death if it is not diagnosed and treated early. It is important to know the risk factors and adopt a culture of prevention through perioperative monitoring of equipment and instruments used during the surgical act.

El oblito o retención de cuerpo extraño después de un procedimiento quirúrgico es un problema real, vigente, prevenible, que afecta la seguridad del enfermo quirúrgico. Su incidencia se desconoce a ciencia cierta, ya que existe un subregistro de su ocurrencia debido al riesgo potencial de demandas.

Caso clínicoMujer de 31 años a la que se le había realizado cesárea electiva, al parecer sin complicaciones. En el postoperatorio mediato presentó cuadro clínico compatible con oclusión intestinal: incapacidad para canalizar gases, distensión abdominal, dolor abdominal y peristalsis de lucha. El diagnóstico se realizó por el antecedente de cirugía abdominopélvica reciente y el hallazgo de cuerpo extraño en la radiografía simple de abdomen. La paciente fue intervenida, el postoperatorio fue satisfactorio y fue egresada por mejoría 5 días después.

ConclusiónEl oblito es un evento subregistrado que representa un problema médico-legal, ya que genera complicaciones diversas. Llega a ocasionar incluso la muerte si no se detecta y atiende con oportunidad. Es importante conocer los factores de riesgo y adoptar una cultura de prevención, mediante la vigilancia perioperatoria del material e instrumentos utilizados durante el acto quirúrgico.

Surgery is a multidisciplinary undertaking, a major experience for the patient and the healthcare team. If one element of surgery fails, the entire process fails, a surgical event therefore carries with it a degree of risk.1,2 Hence medical errors are the eighth cause of death in the USA.3 Human error is avoidable and healthcare systems and doctors, must adopt an open culture of recognition of the error and consequently preventive conduct.

Little is recorded in the medical literature about retained foreign bodies after surgical intervention, because they can result in malpractice litigation.2,4 Yet their presence can cause diagnostic problems, and carry high morbidity and mortality rates.

In 1941, Masciotra5 in a report to the Argentine Society of Surgeons on a foreign body in the bladder, suggested “attaching a name, an appropriate, precise and concise designation for this particular nosological entity”. The term “oblito” (retained foreign body) was adopted as a result of this report (from the Latin oblitum=forgetting). In 2001, the Spanish Royal Academy6 included the term oblito as “any foreign body left inside a patient during surgical intervention” without mentioning its origin or intent.

The real incidence of retained foreign bodies is unknown, due to the systematic lack of autopsies, evacuation through natural orifices, and the absence of reported cases.7

We present the clinical case of a patient who underwent an elective caesarean which was complicated by bowel occlusion in the mediate post-operative period with a final diagnosis of retained foreign body. We also present our review of the medical literature in relation to foreign bodies retained after a surgical procedure.

Clinical caseA 31-year-old female patient, admitted to the obstetrics and gynaecology emergency department, with pregnancy at 39 weeks’ gestation, calculated by the date of last menstrual period, and oligohydramnios. She underwent a Kerr-type caesarean section and bilateral tubal occlusion due to satisfied parity. The surgical procedure was performed with no apparent complications and she gave birth to a male child, weighing 3250g, APGAR 7–8, Silverman 2, Capurro test 38 weeks’ gestation and full swab count.

Twenty-four hours following the surgical procedure, the patient presented diffuse abdominal pain, nausea and inability to channel gas. Physical examination found tegumentary pallor, suboptimal state of hydration, distended, tympanic abdomen, with diffuse pain on palpation, vigorous peristalsis. Her vital signs were: blood pressure 100/60mmHg, heart rate 138/min.

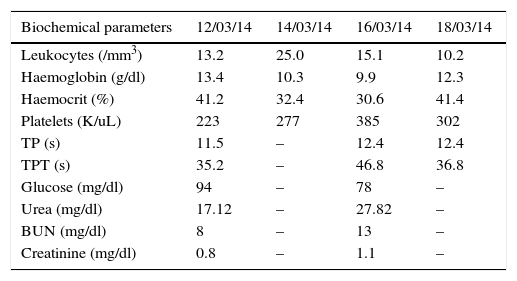

The monitoring laboratory tests showed significant changes compared with those taken on admission, with evident leukocytosis with neutrophilia and grade II anaemia (Table 1).

Laboratory results.

| Biochemical parameters | 12/03/14 | 14/03/14 | 16/03/14 | 18/03/14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes (/mm3) | 13.2 | 25.0 | 15.1 | 10.2 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.4 | 10.3 | 9.9 | 12.3 |

| Haemocrit (%) | 41.2 | 32.4 | 30.6 | 41.4 |

| Platelets (K/uL) | 223 | 277 | 385 | 302 |

| TP (s) | 11.5 | – | 12.4 | 12.4 |

| TPT (s) | 35.2 | – | 46.8 | 36.8 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 94 | – | 78 | – |

| Urea (mg/dl) | 17.12 | – | 27.82 | – |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 8 | – | 13 | – |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.8 | – | 1.1 | – |

BUN: blood uric nitrogen; PT: prothrombin time; PTT: partial thromboplastin time.

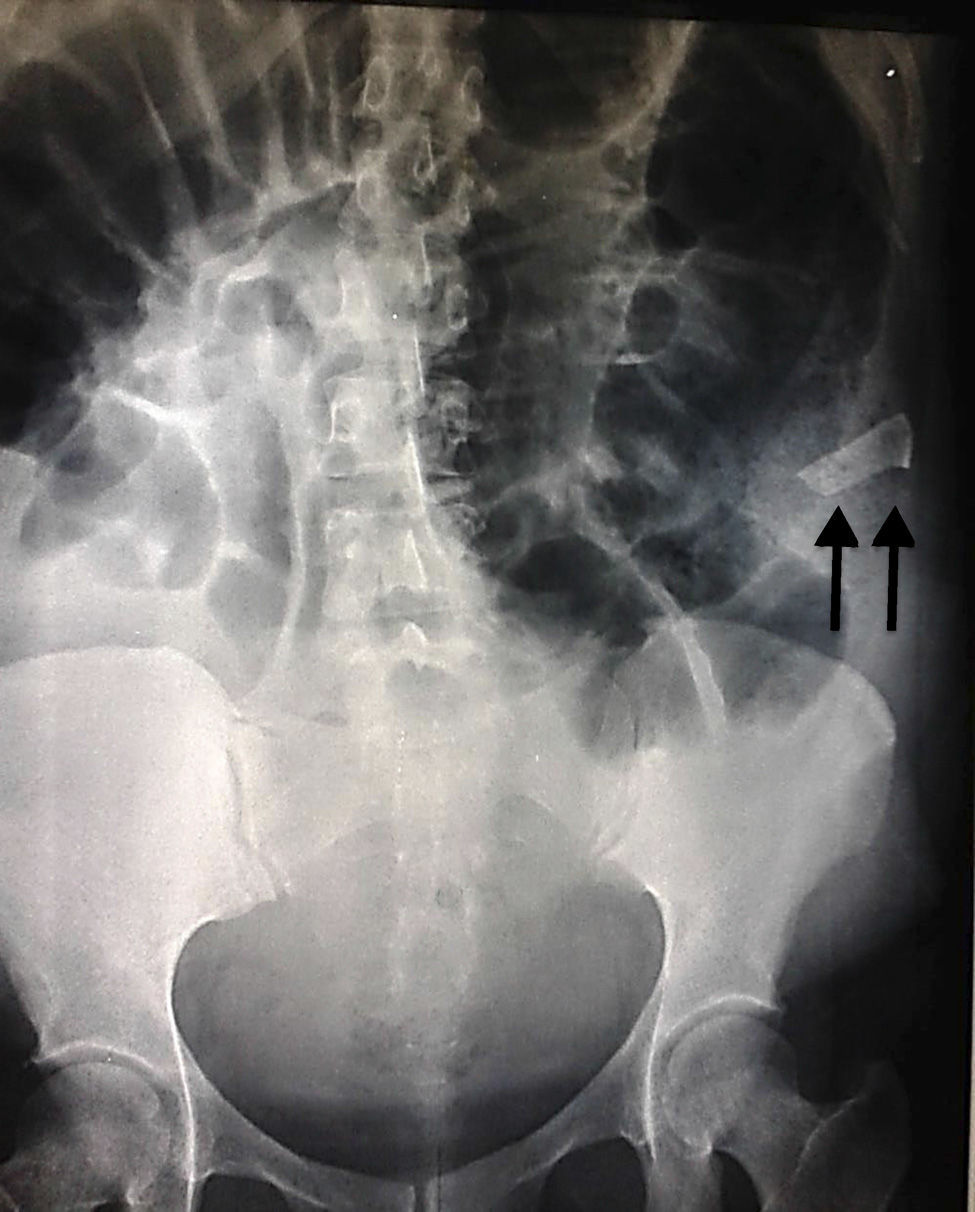

Abdominal X-rays (Figs. 1 and 2) showed significant distension of the intestinal loops, interloop oedema, absence of gas in the rectal ampulla, fluid-air levels and the image of a foreign body in the upper left quadrant.

Given the above, a diagnosis of intestinal occlusion secondary to a foreign body was made, and therefore an exploratory laparotomy was performed. The procedure was reported complication-free, finding a piece of textile lodged in the upper left quadrant, hardened and adhering to the intestinal loops, with friable, oedematous surrounding tissue, and peritoneal reaction fluid estimated to be approximately 100ml.

The patient was treated with double antimicrobial coverage (ceftriaxone 1g q.12h IV and clindamycin 600mg q. 8h IV), analgesics and transfusion of 2 units of packed blood cells and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma. During inpatient management after the exploratory laparotomy, the patient made satisfactory progress. Three days after surgery, the patient started an oral, liquid diet, which was well tolerated. On the fifth postoperative day the patient's condition had improved and she was discharged.

DiscussionRetained foreign bodies (fabric or instruments, including needles), also known as “gossypiboma”,7 after a surgical procedure is a real, current and preventable problem which affects the safety of the surgical patient. Its intermittent and under-recorded occurrence causes serious consequences to patient health, increases the risk of morbidity and mortality which in turn increases medical care costs, and ultimately has a negative impact on public health.8

The incidence of retained foreign bodies is not known exactly, because they are under-recorded due to the potential risk of litigation.9 However, several studies mention that the incidence of retained foreign bodies is variable; some authors estimate it at 0.5–1% per 10,000 surgical procedures.10,11 Fortunately with the increasing use of laparoscopic (minimally invasive) surgery its incidence has reduced considerably.12

Some studies report various risk factors associated with retained foreign bodies,10,12,13 associated with the surgery, the surgeon, ancillary staff and the patient. (a) Associated with the surgery: emergency procedures, prolonged surgery, procedures performed at night, procedures with major bleeding, procedures where there are sudden changes of plans or surgical technique, and when multiple procedures are undertaken in the same operation. (b) Associated with the surgeon: changes in exposure of surgical fields, fatigue, lack of leadership and discipline on the part of the surgeon, indiscriminate use of a mobile phone during surgical interventions. (c) Associated with ancillary staff: staff changes during surgery, fatigue. (d) Associated with the patient: major bleeds (above 700ml), high body mass index.

Approximately 80% of retained foreign bodies are sponges, gauze swabs (these are the most common items in the surgical field, they change position and appearance, and go unnoticed)10 and surgical fields containing cellulose fibres which are not absorbed by the human body. Drainage systems and metal objects such as scissors, needles or forceps are less common.13

The most frequent reports of retained gauze swabs or dressings follow abdominal and gynaecological surgery, each representing 40% of the total cases reported in the literature.14–16 But retained foreign bodies are not exclusive to abdominal or pelvic surgery, they have also been described associated with other types of operations, such as thoracic surgery, cranial surgery, inguinal surgery and in other sites after orthopaedic surgery.17–20 Gawande et al. in 200310 described the most common sites of retained foreign bodies as follows: the abdomen or pelvis 54%, vagina 16–22%, thorax 7.4%, and other sites 17% (spinal canal, face, brain, limbs).

From a pathophysiological perspective, retained foreign bodies can cause 2 types of reaction: (1) aseptic fibrosis, with the formation of adhesions and capsules that lead to granuloma and (2) exudative fibrosis, that form an abscess with or without bacterial colonisation.13,21,22 The sequence of events is as follows: after 24h exudative inflammation presents; from the eighth to the thirteenth day, granulomatous inflammation with a distinctive pattern of chronic inflammation, characterised by aggregation of activated macrophages that take on the appearance of enlarged squamous cells surrounded by lymphocytes, fibroblasts and connective tissue, whose function is to contain the aggressor: these cells cause adhesion to neighbouring tissues. After 5 years they might disintegrate, calcify and less often, ossify.2,13,23 Even using gloves (because of their talc content) or the presence of suture materials can cause inflammatory reactions as they act like foreign bodies, and cause adhesions or granuloma which due to sutures present in approximately 18–37% of patients.24

The clinical picture can start in the mediate postoperative period or even months or years after surgery. Clinical manifestations relate to the anatomical site in which the foreign body is lodged, and the type of inflammatory response triggered. However, clinical manifestations can be very variable and non-specific and can include pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, hyporexia, diarrhoea, digestive tract haemorrhage (upper or lower), functional incapacity, intestinal obstruction (when lodged in the abdominal cavity) and can even cause death.8,13,25,26 It is important to mention that up to 30% of patients with a retained foreign body can be asymptomatic.2,11,27

Diagnosis is incidental and based on radiological studies which are generally simple, since simple X-ray can identify gauze swabs and sponges marked with radio-opaque material in up to 90% of cases and the classical radiological pattern is honeycomb or breadcrumb, which corresponds to the sponge infiltrated by secretions and gas. However, this image is not characteristic and can be confused with an image of faecal material, but its topography outside the colic framework and its persistence on different X-rays rule out this possibility.2 The remaining 10% require advanced imaging studies, such as ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. In this regard, ultrasound is extremely useful because of its speed, its relatively low cost and its availability in almost all medical units. Three types of findings have been described using this method12,28: (1) echogenic area with posterior acoustic shadow and hypoechogenic periphery, produced by the folds formed by the foreign body. (2) Well-defined cystic mass with avascular undulated echogenic centre (visualised using colour Doppler technique), which differentiates it from a complex cyst and sometimes can have a posterior acoustic shadow. (3) Non-specific pattern with hypoechogenic mass and acoustic shadow.23,29,30

The presence of a mass with a well-defined wall, clear contours, fluid air levels, spiral or spongiforme and, intra-abdominal free fluid can be seen on the CT scan13; trapped gas can also be seen inside the gauze swab. In the case of chronicity, calcifications might be present in the cavity wall or a contrast enhancing halo, or it might only appear to be a non-specific cystic mass.28

Differential diagnosis should be made with other abdominal disorders in patients with a surgical history, given the non-specific clinical picture. Disorders such as abscesses, organised haematoma, cysts in any location and organ-dependent, tumour lesions, pseudocystic masses, faecalomas and intestinal tuberculosis, and others should be taken into consideration.23,29

Once the diagnosis of a foreign body has been confirmed, treatment is to surgically extract it promptly in order to reduce the risk of complications, which include: intestinal occlusion, perforation or visceral erosion, enterocutaneous fistulae, mass effect (pseudotumoral syndrome), abscesses. Progression to serious sepsis has been reported in up to 43% of cases.2

Many procedures have been described for prevention: careful review of the operating field, swab and instrument count, marked swabs, uncut swabs, only large swabs in wide cavities, and the use of X-ray should be considered if there has not been a correct count. It is undoubtable that all measures to avoid leaving a foreign body during surgery are welcome, in the knowledge that there is no method which is 100% safe and this fallibility obliges all healthcare staff involved to comply with and verify all the required monitoring methods.

Some recommendations have been proposed to prevent retained foreign bodies, designed for the participation of each member of the surgical team (scrub nurse, surgeon and circulating theatre nurse, etc.) and to suit the features of the operating theatre,14 amongst which are highlighted: carefully counting all material placed on the instrument table for the operation (especially any fabric which is to be used) and when the swab and sponge packets are being opened at the start of the operation and each time a new packet is received; keeping a tidy instrument table throughout the entire intervention to facilitate counts and prevent material being lost; informing the rest of the surgical team immediately when materials are left in the operating area, indicating where the material is left and how many units are being used (this will encourage the attention and responsible participation of all those involved, it will also enable their extraction and, if necessary searching for them if any are missing at the end of the operation); informing the surgical team when this material that has been left is removed, saying what type it is and how many units are being removed, to keep the count under control; waiting until the scrub nurse informs the result and number of counts performed before closure of the surgical field.

ConclusionA retained foreign body is an under-reported event which is a medical-legal problem because it causes diverse problems. It can even cause death if not detected and dealt with promptly, in addition to increasing care costs, because the patient has to be readmitted and reoperated at least once.

It is important to be aware of the risk factors and adopt a culture of prevention by perioperative monitoring of the material and instruments used during surgery, since everybody is capable of error regardless of their experience, and since a retained foreign body can occur in any invasive procedure, and can even result in serious medical-legal consequences.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Balcázar-Rincón LE, Gordillo Gómez EA, Ramírez-Alcántara YL. Oclusión intestinal secundaria a oblito quirúrgico. Cir Cir. 2016;84:503–508.