During the COVID pandemic, elective global surgical missions were temporarily halted for the safety of patients and travelling healthcare providers. We discuss our experience during our first surgical mission amidst the pandemic. We report a safe and successful treatment of the patients, detailing our precautionary steps and outcomes.

MethodsRetrospective manual chart review and data collection of patients’ charts was conducted after IRB approval. We entail our experience and safety steps followed during screening, operating and postoperative care to minimize exposure and improve outcomes during a surgical mission in an outpatient setting during the pandemic. The surgical mission was from February 8 to February 12, 2022.

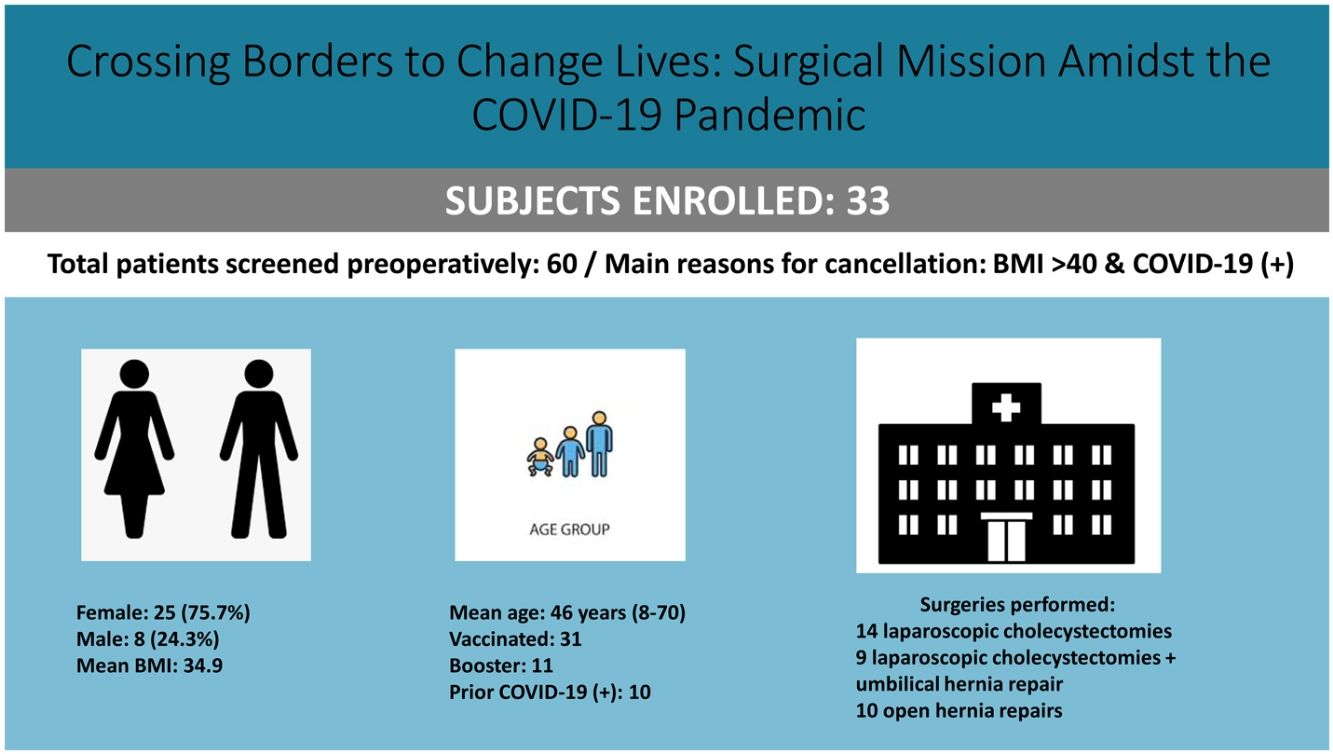

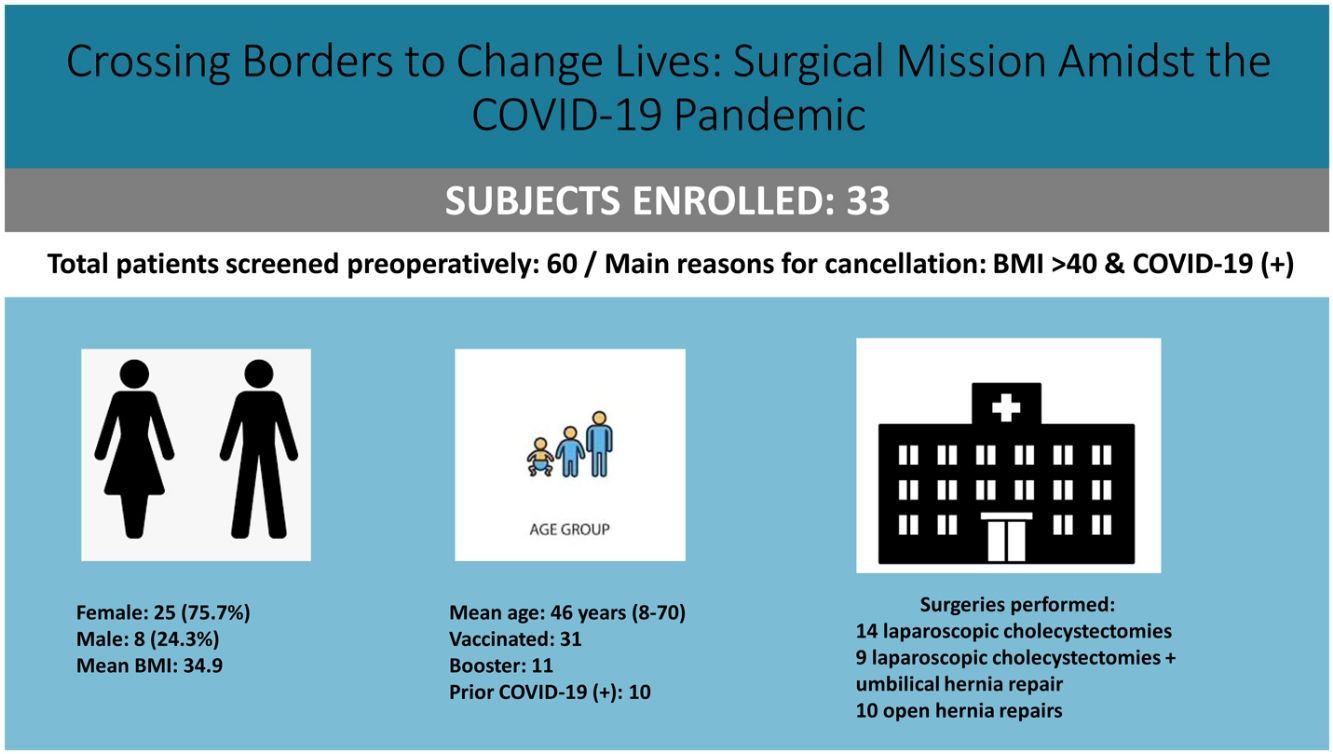

ResultsA total of 60 patients who were screened. 33 patients underwent surgical intervention. One patient required postoperative hospitalization for a biliary duct leak. No patient or healthcare provider tested positive for COVID at the end of the mission. The average age of patients was 46.9 years. The average operative time was 116 min, and all patients had local nerve blocks. It included 45 health work providers.

ConclusionsIt is safe to perform outpatient international surgery during the pandemic while following pre-selected precautions.

Durante la pandemia de COVID, las misiones quirúrgicas globales electivas se detuvieron temporalmente por la seguridad de los pacientes y los proveedores de atención médica que viajaban. En el presente trabajo presentamos nuestra experiencia durante la primera misión quirúrgica en medio de la pandemia. Reportamos el tratamiento seguro y exitoso de los pacientes, detallando nuestros pasos de precaución y resultados.

MétodosLuego de obtener la aprobación del IRB, se realizó la revisión manual retrospectiva de las historias clínicas y la recopilación de datos de las historias clínicas de los pacientes. Exponemos nuestra experiencia y los pasos de seguridad seguidos durante la detección, la operación y la atención posoperatoria para minimizar la exposición y mejorar los resultados durante una misión quirúrgica en un entorno ambulatorio durante la pandemia. La misión quirúrgica fue del 8 al 12 de febrero de 2022.

ResultadosUn total de 60 pacientes fueron tamizados. De ellos, 33 pacientes fueron intervenidos quirúrgicamente. Un paciente requirió hospitalización postoperatoria por una fuga del conducto biliar. Ningún paciente o proveedor de atención médica dio positivo por COVID al final de la misión. La edad media de los pacientes fue de 46,9 años. El tiempo operatorio promedio fue de 116 min, y todos los pacientes tuvieron bloqueos nerviosos locales. Participaron 45 proveedores de trabajo de salud.

ConclusionesEs seguro realizar una cirugía internacional ambulatoria durante la pandemia siguiendo las precauciones preseleccionadas.

The spread of COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) has considerably impacted and overwhelmed the healthcare system, halting elective global surgical initiatives due to the highly infectious and morbid impact of the virus. The risk of transmitting COVID-19 in flight is estimated to be 1 per 1.7 million travelers1. With that low transmission rate, efforts to mitigate transmission of the virus, other than particulate air filtration and social distancing, routine pre-travel testing for asymptomatic patients has shown in simulated studies to be effective in reducing passenger risk of infection2.

Inguinal hernias are reported by the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund to be the fourth leading cause of morbidity among male discharges in the Americas3. More than 75% of the general population in Ecuador are covered only by the overwhelmed Ministry of Health system to undergo surgical interventions, thus, many of the underprivileged patients live with decades of pain due to chronic cholecystitis and growing hernias4. In our experience, many of the patients we operated on presented with chronic cholecystitis pending surgical intervention. We aimed to share our experience and review the outcomes of global elective surgical procedures during the pandemic in the ambulatory setting.

MethodsThis study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for data collection and publication. We retrospectively reviewed and collected data from patients who attended the Centro Clínico Quirúrgico Ambulatorio “Blanca’s House Ecuador Hospital del Día” from February 8, 2022 to February 12, 2022. We collected data pertaining to demographics, procedure types, vaccination status, booster status, prior COVID infection, comorbidities, type of anesthesia administered, block type, operative time, follow-up, and complications.

We organized a surgical mission with two surgeons, five anesthesia providers, a surgical resident, two physician assistants, a nurse practitioner, four nurses, and two surgical technicians. We operated in a clinic that was recently renovated to accommodate two operating rooms. All the surgical instruments were disinfected with glutaraldehyde (Cidex®). The plan was to operate for half a day on the day of arrival, allowing staff to get accustomed to the new setting and the available equipment. The teams operated the first day for 8 h, the 2nd–5th days the teams operated for 12 h, and the 6th and final day for 8 h. The postoperative follow-up was carried out by the surgical team in Ecuador's Centro Clínico Quirúrgico Ambulatorio “Blanca’s House Ecuador Hospital del Día”. All patients were evaluated within two to three weeks from their procedures.

All staff members were required to be vaccinated and to have received a booster dose prior to travel. They were also required to obtain RT-PCR (Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction) COVID testing within two days from the departure to meet travel requirements. Staff were also asked about COVID symptoms prior to travelling and at the arrival destination.

Learning from our experience in the United States, with the increased use of telehealth as a mean to assess new patients and follow ups during the pandemic, our team carried telehealth consultations via an online video conference platform to screen all the patients5. Prior to the telehealth consultation, the patients were assessed and triaged by the local surgical team in Ecuador. Lowering exposure to both patients and health staff. Both an anesthesiologist and surgeon evaluated the patients, along with a Spanish speaking interpreter.

The goal of preoperative COVID testing in asymptomatic patients is to detect viral ribonucleic acid in the pre-symptomatic phase. Preoperative testing is important and cost effective in areas with high prevalence of infected patients to recognize COVID positive patients and to limit exposure to the staff and other patients6. During our visit, the Omicron variant had a high prevalence in Ecuador, necessitating COVID testing.

Querying patients for COVID-19 symptoms could be unreliable, as some patients have been waiting for the surgical opportunity for months/years and would not declare symptoms for the sake of undergoing the surgical intervention. Thus, all patients underwent RT-PCR COVID testing 2 days prior to surgery and were excluded if they had positive results, keeping in mind the limitation of RT-PCR with a sensitivity rate of 70% in diagnosing COVID-19. As an extra precautionary step, patients also underwent rapid IgG/IgM (Immunoglobulin G/Immunoglobulin M) testing the day of surgery. In our experience the initial RT-PCR test was useful to exclude patients who tested positive whether symptomatic or not.

It is important to note that we forwent IgG/IgM testing later during the mission, as two patients had positive antibody testing the day of surgery but had negative RT-PCR testing 2 days prior and had no signs of COVID-19 on exam. We elected to use RT-PCR as the sole reliable test along with physical exam to help exclude patients.

Commuting included a hotel van service transporting the healthcare providers from the hotel to the clinic and back, reducing exposure during the mission.

A hotel was chosen as the site of stay, as the hotel rooms could have been utilized for quarantine in case of COVID exposure, evidence of symptomatic COVID-19, or positive COVID-19 RT-PCR testing.

One family member was allowed to escort the patient to the hospital. As this was elective outpatient surgery, the patients were overall healthy and didn't need aid with ambulation.

Families got in touch with the patients via telephone and once the patients were stable for discharge (after a night's sleep in the medical center), the family would be waiting outside the center in a waiting area to receive their family members. The exception was for kids, one parent would be allowed to accompany the child to the operating room and then would wait outside until after the procedure where they would be allowed to be at bedside in the recovery room.

Statistical analysisA statistical analysis has not been performed in this manuscript due to its nature, in which the correct design and the follow-up of pre-established guidelines for the prevention of COVID-19 during a surgical mission amidst the pandemic are mainly discussed.

ResultsA total of 60 patients were screened preoperatively, 33 of which underwent surgery (14 laparoscopic cholecystectomies, 9 laparoscopic cholecystectomies along with umbilical hernia repair, and 10 open hernia repairs).

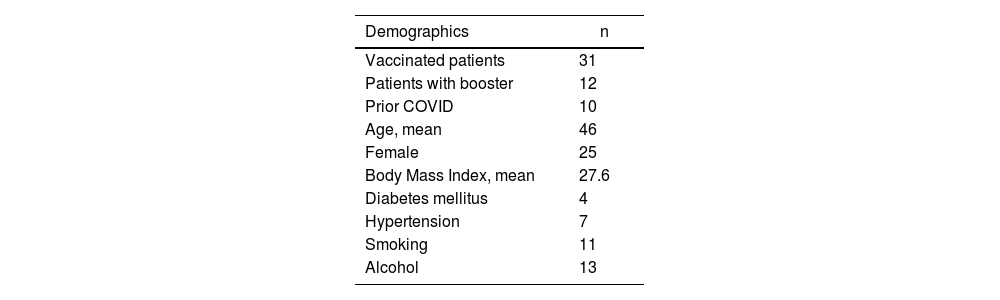

Two of the 33 patients undergoing surgery had not received COVID vaccination. Type of vaccination and booster status, and comorbidities and demographics including age, sex, comorbidities, and social history are included in Table 1.

Demographics and procedures.

| Demographics | n |

|---|---|

| Vaccinated patients | 31 |

| Patients with booster | 12 |

| Prior COVID | 10 |

| Age, mean | 46 |

| Female | 25 |

| Body Mass Index, mean | 27.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 |

| Hypertension | 7 |

| Smoking | 11 |

| Alcohol | 13 |

One patient required hospitalization after discharge from our ambulatory center, requiring ERCP (Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio-Pancreatography) and stent placement for a bile leak. Otherwise, three patients had incisional inflammatory/infectious changes requiring a repeat course of antibiotics.

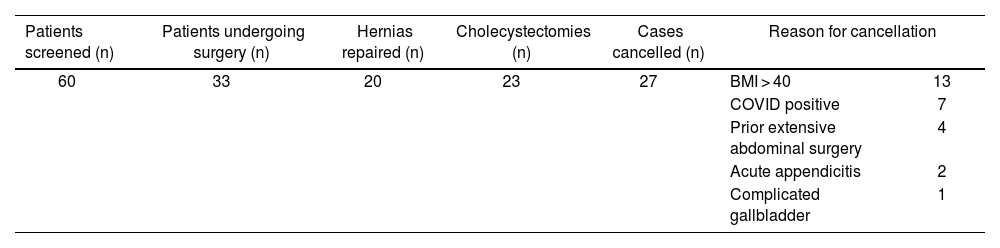

In Table 2 is shown the types of procedures performed in total and the numbers of excluded patients and reason for exclusion. Body Mass Index (BMI) greater than 40 and COVID-19 positive test were the two most common causes for surgical exclusion during patient screening. Table 3 highlights the estimated sum of monetary donated resources and services in US dollars if the procedures were to be performed in the United States.

Types of surgery performed and reasons of cancellation.

| Patients screened (n) | Patients undergoing surgery (n) | Hernias repaired (n) | Cholecystectomies (n) | Cases cancelled (n) | Reason for cancellation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 33 | 20 | 23 | 27 | BMI > 40 | 13 |

| COVID positive | 7 | |||||

| Prior extensive abdominal surgery | 4 | |||||

| Acute appendicitis | 2 | |||||

| Complicated gallbladder | 1 | |||||

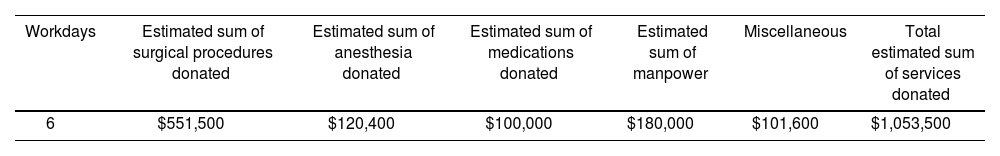

Estimated sum of resources and procedures donated (in US dollars).

| Workdays | Estimated sum of surgical procedures donated | Estimated sum of anesthesia donated | Estimated sum of medications donated | Estimated sum of manpower | Miscellaneous | Total estimated sum of services donated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | $551,500 | $120,400 | $100,000 | $180,000 | $101,600 | $1,053,500 |

Following the mission’s protocols and precautions, none of the travelling healthcare providers tested positive for COVID, neither did the staff nor patients in Ecuador. Our workforce included 45 healthcare workers. None of the providers had COVID symptoms immediately prior to the mission.

All the cholecystectomies during our mission were performed laparoscopically and all hernias were repaired via open approach. Either mesh or sutures were used to repair the hernias, depending on defect size and BMI of the patients. All the procedures were done under general anesthesia along with either a Transversus Abdominis Plane block or an inguinal block using bupivacaine.

Staff were required to wear surgical masks in the facility. Staff were not mandated but encouraged to wear N95 masks.

Each surgeon operated with either another surgeon, surgical resident or physician assistant. Medical students were encouraged to observe and learn during the surgery.

Interestingly, none of the patients received narcotics postoperatively, which coincides with the same findings Leon Herszage published in 2004, where all patients ambulated immediately after surgery and had no issues with pain control7. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen were used for pain control in the recovery room and after discharge. All patients received prophylactic antibiotics in the recovery room and on discharge for seven days.

From prior experience, some patients were lost to follow-up after surgery as they came from rural areas, thus all patients were admitted overnight in the clinic and were examined by the surgical team before discharge. Patients were also seen within two to three weeks postoperatively for follow-up, this was achieved by having patients undergo a clinical assessment at the clinic in Ecuador and through telehealth consultations. None of the patients had complications immediately postoperatively and only one patient had a complication after discharge, where he developed a cystic duct leak requiring ERCP and stenting.

Surgical services provided by internationally travelling healthcare providers in the form of surgical mission trips to underserved communities might represent a cost-effective and viable option for communities with unmet surgical needs of their populations8. If those procedure were to be performed in the United States, the total estimated sum of services would sum up to about $1 million as detailed in Table 3.

DiscussionThe pandemic placed a cog in the wheel of global surgery. The rapidly instituted travel and safety restrictions made international travel difficult. Travel restrictions on health care providers by healthcare institutions hindered the organization of surgical missions during the pandemic. Most elective surgeries were paused in highly populated cities during the height of the pandemic9. Global surgical missions were paused for a longer period due to the pandemic.

Resource-poor countries with baseline difficult patient access to surgical services during the pandemic were overwhelmed with symptomatic COVID patients. An overwhelmed system along with initial unknown operative outcomes in COVID positive patients lead to a transient suspension of elective surgery, prolonging the surgical wait time and queue for an elective procedure, particularly in low-income countries.

As surgeries were resumed during the pandemic, data showed that postponing elective surgery and adopting non-operative management, when reasonable, should be considered in COVID positive patients, especially in elderly males10,11.

After a two-year interruption to our surgical missions, we resumed our 20-year long history of surgical missions in early 2022 with recent alleviation of travel restrictions.

In January 2022 the American College of Surgeons stated that “Maintaining access to surgery is an essential part of quality patient care, whether the surgery is needed to cure a medical condition, address infirmity, extend life or contribute to patient well-being”. Once making the correct adjustments on surgical services based on local case incidence, ongoing testing of staff and patients, aggressive use of appropriate personal protective equipment and physical distancing practices are required12. Elective surgical procedures such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy and hernia repairs during the pandemic can potentially have improved outcomes by having a COVID-19 oriented protocol regarding travel and patient screening. During our process we set up a protocol to set a course of action when there are patients who test positive for COVID-19, with set transportation, postoperative care and follow-up.

We conclude that global elective surgery during the COVID pandemic is safe with good patient outcomes. Early pre-set guidelines for the mission and staff could allow for a harmless experience.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.