Metastatic lymph node affectation is the main prognostic factor in localised lung cancer. Pathological study of the obtained samples even after an adequate lymphadenectomy presents tumoral relapses of 40% of stage I patients after oncological curative surgery. In this paper we have studied micrometastasis in the sentinel lymph node by molecular methods in patients with stage I lung cancer.

Material and methodsThe sentinel node was marked by injecting peritumorally performed just after performing the thoracotomy with 2mCi of nanocoloid of albumin (Nanocol®) marked with 99mTc in 0.3ml. Guided with a Navigator® gammagraphic sensor, we proceeded to its resection. RNA of the tissue was extracted and the presence of genes CEACAM5, PLUNC and CK7 in mRNA was studied.

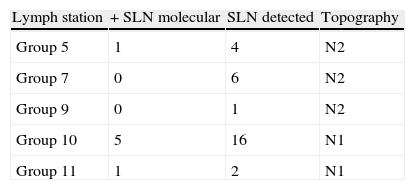

ResultsTwenty-nine patients were included. Of the tested genes, CEACAM5 and PLUNC were the ones that showed a high expression in lung tissue. Of the 29 analysed sentinel lymph nodes, 7 (24%) were positive in the molecular study. A positive sentinel lymph node was found in 4/7 adenocarcinomas and 3/12 squamous-cell tumours. Affected lymph nodes were: station 5 (1/3), station 7 (0/6), station 9 (0/1); station 10 (5/11); station 11 (1/1).

ConclusionsDetection of sentinel node in patients with stage I lung cancer by marking with radioisotope is a feasible technique. The application of molecular techniques shows the tumoral affectation in cases staged as stage I.

La afectación metastásica a nivel ganglionar es el principal factor pronóstico en el carcinoma pulmonar localizado. Pese al estudio anatomopatológico de las piezas obtenidas tras una adecuada linfadenectomía mediastínica, la recidiva tumoral alcanza el 40% en pacientes estadio i tras la cirugía oncológica curativa. En este trabajo hemos realizado el estudio de micrometástasis por métodos moleculares en el ganglio centinela de pacientes con carcinoma pulmonar estadio i.

Material y métodosMarcaje del ganglio centinela mediante la inyección peritumoral de 2mCi de nanocoloide de albúmina (Nanocol®) marcado con 99mTc en un volumen de 0,3ml tras la toracotomía. Guiados mediante la sonda gammagráfica Navigator® se procedió a su localización y exéresis. Se extrajo ARN de los tejidos y se analizó la presencia de ARNm de los genes CEACAM5, PLUNC y CK7.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 29 pacientes. De los genes testados, el CEACAM5 y el PLUNC fueron los que mostraron una alta expresión en tejido pulmonar. De los 29 ganglios centinela analizados, 7 (24%) fueron positivos para estudio molecular. Se encontró ganglio centinela positivo en: 4/7 adenocarcinomas y 3/12 escamosos. Los ganglios afectos fueron: nivel 5 (1/3), nivel 7 (0/6), nivel 9 (0/1), nivel 10 (5/11), nivel 11 (1/1).

ConclusionesLa detección del ganglio centinela en pacientes con carcinoma pulmonar estadio i mediante marcaje con radioisótopo es factible. La aplicación de técnicas moleculares pone de manifiesto la afectación tumoral en casos estadificados como estadio i.

Mediastinal lymphadenectomy in lung cancer is a standard procedure. In TNM, the special tropism of pulmonary neoplastic cells through the lymphatic territories makes an appropriate and exhaustive study of the mediastinal lymph nodes essential for disease staging. Lymph node involvement from metastasis is a particularly relevant prognostic factor in lung cancer.1

The same as with tumour size, the greater the number of lymph nodes affected correlates with their spread to other regions and a poorer prognosis.2 In lung cancer, lymph node classification is governed by the absence (N0) or presence (N1–3) and location of lymph node involvement. Descriptors N1–3 indicate the lymph node location: the higher the N is, the greater the distance from the primary tumour and the poorer the prognosis.

This information on the prognostic impact of the number of lymph nodes involved has been made possible through lymph node extirpation and analysis.

The greater the number of lymph nodes extirpated, the better the prognosis, even for stage I pathological tumours, although there is no consensus as to the ideal number of lymph nodes to be retrieved: in published retrospective studies, this number varies between six and fifteen,3,4 with ten as a recommendation.5

Systematic node dissection6 is generally recommended for mediastinal lymphadenectomy. This technique offers the highest guarantee for correct staging to both certify and define the lymph node involvement or confirm its absence.

The effort put into studying lymph nodes obtained through surgery using new techniques is to optimise the yield of the specimens and to increase the possibility of a cure by establishing a treatment in line with disease staging.

The study of lymph node micrometastasis has been published as a negative prognostic factor.7 In a study published by our group8 the existence of lymph node micrometastasis found using molecular methods was a factor of faster tumour recurrence. However, the great number of lymph nodes examined per patient was a parameter which rendered its systematic application impractical for us.

The introduction of the sentinel lymph node (SLN) concept – well known in breast cancer and melanoma – helped towards the detection of SLN in lung cancer. There are many limitations concerning its systematic application requiring homogeneity and validation.

The aim of this paper is to present our experience in SLN marking in lung cancer patients and its molecular examination looking for micrometastasis.

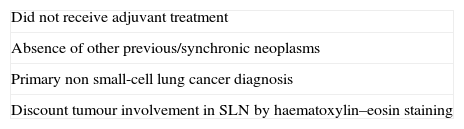

Materials and MethodsIn a patient with inclusion criteria (Table 1), we proceeded to mark the SLN with 2mCi albumin nanocolloid peritumoral injection (Nanocol®) marked with 99mTc 0.3ml volume after thoracotomy. After at least 15min and guided with the Navigator gammagraphic probe®, we proceeded to locate and excise them.

We collected healthy, tumoral and SLN tissue from all the patients with non-microcytic lung carcinoma at stage 1 at the time of surgery, in the shortest possible time (<30min), to preserve their mRNA as intact as possible.

Part of the tissue (lung, normal, tumour and SLN) was immediately frozen and stored in a freezer cabinet at −80°C. We routinely processed the rest as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded-tissue, using haematoxylin–eosin and immunohistochemical staining of sections (CKAE1/3; CK7; CK19).

For the immunohistochemical study, the standard technique (avidin–biotin complex) was used, in an automatic immunostainer (TechMate 500; Biotech Solutions, Dako, Dinamarca), assessing immunoreactivity for CKAE1/3, CK7 and CK19, the standard histological markers for lung tissue.

The lymph node remitted as sentinel for immunohistochemical and molecular study was dissected. Two-thirds of the lymph node were processed for conventional anatomopathological study and a third was stored in 1ml de RNAlater™ (QIAGEN), marked with the patient's name and date of birth. The mRNA for RT-PCR was then extracted from this material.

The gene expression markers CK7, CEACAM5 and PLUNC were chosen for the detection of occult metastasis by RT-PCR molecular technique. GADPH was used for gene expression control, which enabled us to evaluate the sample quality and standardise the result of the expression study.

The selection of these three markers was based on the work of Benlloch et al.8 where an extensive search in the SAGE catalogue (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Catalog; Lash et al.)9 was made, aimed at selecting genes with high lung tissue expression and low or zero benign lymph node expression. Genes CK7, CEACAM5 and PLUNC were selected as the most specific in detecting lung metastasis. Therefore, lymph nodes expressing at least two of the genes marking the presence of cells of lung origin were considered molecular positives.

The fraction of tumour tissue, normal lung tissue and SLN tissue was handled sterilely and maintaining cold. Titration was performed in TissueLyser® (QIAGEN) equipment, following the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. Homogenisation was carried out, followed by RNA extraction using the QIAGEN RNA Mini Kit™ (QIAGEN) in an automatic nucleic acid extractor (Qiacube™, QIAGEN, …). The RNA obtained from the samples was quantified using the NanoDrop 2000® (NanoDrop Technologies) spectrophotometer. We proceeded to obtain cRNA through RT-PCR using the GeneAmp RT-PCR™ (Applied Biosystems) kit from 1μg of total RNA using random hexamers, according to manufacturer's instructions. The cRNA was stored at −80°C until use.

The gene expression assay was conducted in a ABI7500® (Applied Biosystems). The primers, the probes and the Taqman Universal MX™ were purchased from Applied Biosystem. 2.5μl of cRNA was used for PCR amplification. Each sample was tested in triplicate. Negative and positive controls were included in all assays. The PCR conditions were: initial incubation at 50°C for 2min to activate the AmpErase UNG™; followed by 10min at 95°C to activate the AmpliTaq Gold polymerase™, followed by 50 cycles at 95°C for 15s and at 60°C for 1min. The tumour tissue and normal lung tissue of each patient served as positive control. Primers and probes were acquired as assay – on-demand from Applied Biosystems (CK7 Hs00559840_m1, CEACAM5 Hs00237075_m1, PLUNC Hs 00213177_m1). Amplifications included exon combinations for cRNA specificity and avoidance of possible contaminating genomic ADN amplification. Each patient's tumoral lung tissue was used as positive control in the tested genes expression. GADPH (Hs02758991_g1) gene expression was used as endogenous quality control of the sample and the amount of tested mRNA.

ResultsThe sample included 42 patients. Thirteen patients were excluded from initial recruitment because two presented benign tumours, three metastatic tumours and eight where the SLN was found to be affected by metastasis in conventional haematoxylin–eosin staining.

29 patients were included: 21 men with an average age of 64.28 (range: 49–79). Mean tumour size was 27.86±16.2mm (range: 8–65mm). Twenty lobectomies, one bilobectomy, one pneumonectomy and seven segmental resections were performed.

Average waiting time between administration of the radiopharmaceutical and SLN identification was 59min (range: 28–125min).

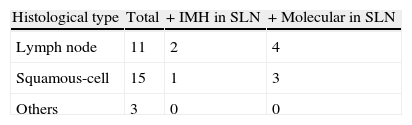

Histological types were: 11 adenocarcinomas, 15 squamous cell cancers, 2 neuroendocrine cancers and 1 adenosquamous carcinoma.

Of the tested genes, the CEACAMS and PLUNC showed a high expression in lung tissue and low or zero lymph node tissue unaffected by the tumour. Of the 29 tested SLN (Table 2) seven (24%) were positive in the molecular study. Of these, three also showed positive cytokeratin (CK7). Positive SLN was found in: 4/7 adenocarcinomas and 3/12 squamous-cell cancers. Molecular testing of SLN is shown in Table 3.

The statistical programme SPSS version 20 was used for the analysis. Descriptive statistics of the variables, percentages, means and standard deviations were calculated.

No reliable statistical estimate can be made for sample size calculation due to insufficient testing in similar conditions. Medical literature was consulted to evaluate sample size compared with similar testing.

DiscussionLymphatic metastatic involvement is the main prognostic factor in localised lung cancer.10 TC image or nuclear medicine (PET-TC) methods used for detection produce a number of false negatives which are of great value for the establishment of appropriate disease staging prognosis and treatment. Despite the correct anatomopathological study of tissue obtained after mediastinal lymphadenectomy, stage I patients present with 40% tumour relapses after oncological curative surgery.11 There is little justifiable explanation for this high rate of recurrence.

The existence of micrometastasis not identified using standard methods (haematoxylin–eosin) is considered a plausible explanation. In a previous publication8 we demonstrated the presence of this micrometastasis detected by molecular methods in mediastinal lymph nodes. However, the heavy use of human resources and high financial cost of analysing an average of twelve lymph nodes per patient drew us to focus on SLN detection for molecular analysis, thus lowering costs.

The SLN concept implies that the lymphatic flow of the primary tumour migrates to anatomically adjacent nodes first before migrating to more distant ones.12 As we know, SLN has been well studied in melanoma and breast cancer.13 In lung cancer, the aim of its detection is different to the previously mentioned cases: although an increase in possible complications after mediastinal lymphadenectomy14 has been reported, the reason for molecular study is to avoid substaging (staging as stage I patients who actually present molecular involvement). Evaluation of the impact on prognosis and the treatment possibilities for this patient subgroup is a second, more ambitious step.

SLN detection in the lung presents a number of particularities. The radiolabeled substance must be administered after thoracotomy. The appropriate migration of the marker through the lymphatic pathways remains in question, although Liptay et al.10 reports 92% sensitivity, higher than other techniques such as the ISO sulphate blue injection described by Little et al.15

The lymph node haematoxylin–eosin staining assay showed tumour involvement in eight cases (five in N1 stations). The search for lymph nodes in surgery with a detection probe, anatomically following the described lymphatic pathways enabled us to carry out a more exhaustive study of lung lymph nodes (N1) and detect tumour involvement at this level.

We know the subpleural lymph nodes are directly linked to mediastinal level lymph nodes in 20%–25% of patients.16 We also share the opinion of Nomori et al.17 that SLN in the thoracic cavity is lobule specific. We would logically consider that lymphatic flow stations would be from the lesion towards adjacent nodes (subpleural/intraparenchymatous: considered N1) and in some cases, directly to those considered N218 such as the aortopulmonary window.19 The study of theoretical lymph drainage patterns and correct location of lymph nodes marked specifically by radioisotope at a particular level at the time of surgery could partially explain the skip metastases phenomenon and confirm a more logical pattern of migration, although the prognosis of patients with mediastinal skip metastases (N1− and N2+) is still controversial.20

Our study showed 6/12 level N1 affected lymph nodes and 1/10 N2 nodes, the latter at the aortopulmonary window level. These results are consistent with the previous paragraph.

Regarding histological type, SLN was detected in over half of the adenocarcinomas (57%) and 25% of the squamous cell cancers. More frequent metastatic spread is better known in adenocarcinomas, contrasted in our study.

To conclude, SLN detection in patients with stage I lung cancer by radioisotope marking allows further in-depth study of the adenopathy. The application of molecular techniques highlights its tumour involvement in stage I cases. This at least partly explains the high incidence of disease progression in patients classed as stage I by conventional methods. The prognosis and treatment possibilities for this patient subgroup remain a challenge for further research.

FinancingGIDO (Groupo de Investigación y Divulgación Oncológica-Oncological research and report group) funding for this study was awarded.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Galbis Caravajal JM, Cremades Mira A, Zuñiga Cabrera Á, Estors Guerrero M, Tembl Ferrairó A, Martinez Hernandez NJ, et al. El ganglio centinela en el carcinoma pulmonar. Estudio molecular tras detección con radioisótopo. Cir Esp. 2014;92:11–15.