Approximately 25% of patients with colorectal cancer (CCR) present liver metastases (LM) at diagnosis. The best therapeutic option involves resection of both tumor foci in association with chemotherapy, which provides 5-year survival rates of 20%–50%.1,2 However, few patients are candidates for simultaneous resection, due to either the extent of the liver disease or the combination of 2 surgeries that entail high complexity or risk of morbidity.3

In selected cases, it is possible to perform simultaneous ultrasound ablation (SUA) during the CCR surgery as a curative alternative to major or complex liver resections.

To determine the associated survival, we conducted a retrospective study on patients who underwent SUA exclusively, without liver resection, together with simultaneous CCR resection. The inclusion period was between March 2015 and March 2022, and the follow-up was until December 2022. Patients treated with simultaneous resection and combined SUA for LM (n = 3) were excluded. Likewise, patients with persistent macroscopic disease (R2; n = 2) after CCR resection were also excluded. In all cases, the indication for SUA was previously assessed by a Multidisciplinary Tumor Committee.

During the study period, SUA procedures and CCR resection were performed on a total of 9 patients, representing less than 1% of the total annual elective interventions for CCR. The median age was 81 years (range: 42–85), and 6 were women (66.6%). All but one had an ASA score of 3 (88.8%), with an average Charlson comorbidity index of 11.6 points (SD 2.2).4 Regarding their functional status, all the cases were ECOG 0-1 (88.8%), except for one ECOG 2. The median preoperative CEA was 2.4 ng/mL (1.2-81.8), and only one patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (11.1%). The CCR location was on the right in 3 cases (33.3%), on the left in 2 (22.2%), and in the rectum/sigmoid colon in 4 (44.4%).

In all cases, SUA was performed in the operating room by an Interventional Radiologist, with the patient under local anesthesia and sedation, and immediately before CCR resection in order to unify 2 procedures that are usually performed independently and to optimize the general anesthesia time. In addition, the percutaneous approach was used instead of direct puncture of the liver, since the incisions normally used for colorectal resection do not usually provide good access to the supramesocolic compartment.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound did not detect more LM than those that had been diagnosed preoperatively in any of the patients. A total of 14 LM were treated, using radiofrequency in 5 cases (55.5%) and microwave ablation in cases with a diameter >25 mm and proximity to thermosensitive vascular-biliary structures >2 mm (44.4%). Some 55.5% of the patients had a solitary LM, 33.3% presented 2 LM, and one patient had 3 LM (11.1%). The median lesion size was 13 mm (3–33), and the distribution by segments was as follows: 3 LM in segment III, 2 in segment VI, 5 in segment VII, and 4 in segment VIII. In 5 cases, CCR resection was laparoscopic (55.5%). The average time for both procedures was 270 ± 73 min, while the time for ultrasound-guided percutaneous ablation itself usually ranged from 20−60 min, depending on the number of LM to be treated and the technical difficulty of the approach.

No patient presented major complications (Dindo-Clavien ≥ III5). The median hospital stay was 6 days (4−11), and no readmission was required within 90 postoperative days. Two patients (22.2%) received adjuvant chemotherapy.

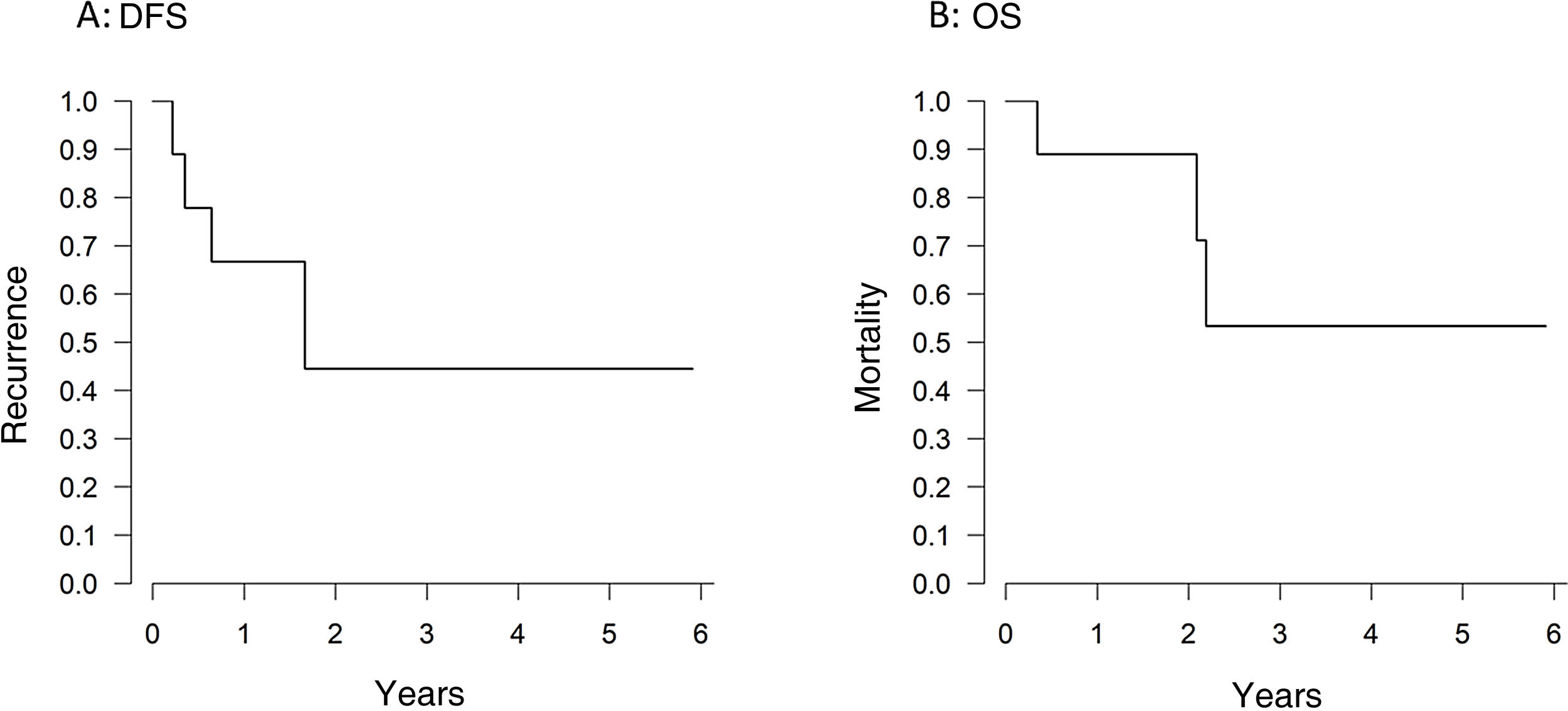

After a median follow-up of 35 months (11–46), one-year and 3-year overall survival and disease-free survival rates were 88.8% and 55.5%, and 66.6% and 44.4%, respectively (Figs. 1A, 1B). Four patients (44.4%) developed disease recurrence. The recurrence was at the ablation site in only one case (11.1%) (Table 1).

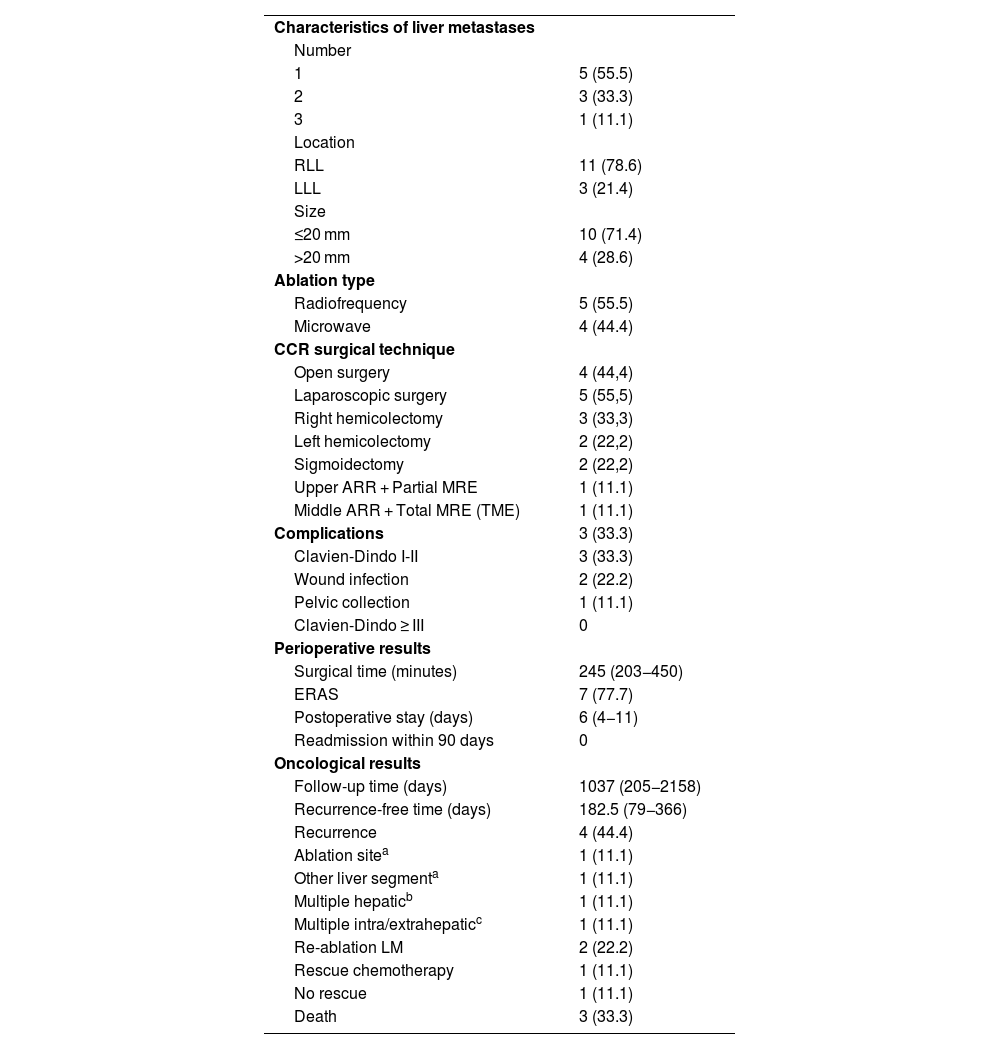

Characteristics of colorectal cancer and liver metastases; surgical and ablative techniques; perioperative variables; survival results.

| Characteristics of liver metastases | |

| Number | |

| 1 | 5 (55.5) |

| 2 | 3 (33.3) |

| 3 | 1 (11.1) |

| Location | |

| RLL | 11 (78.6) |

| LLL | 3 (21.4) |

| Size | |

| ≤20 mm | 10 (71.4) |

| >20 mm | 4 (28.6) |

| Ablation type | |

| Radiofrequency | 5 (55.5) |

| Microwave | 4 (44.4) |

| CCR surgical technique | |

| Open surgery | 4 (44,4) |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 5 (55,5) |

| Right hemicolectomy | 3 (33,3) |

| Left hemicolectomy | 2 (22,2) |

| Sigmoidectomy | 2 (22,2) |

| Upper ARR + Partial MRE | 1 (11.1) |

| Middle ARR + Total MRE (TME) | 1 (11.1) |

| Complications | 3 (33.3) |

| Clavien-Dindo I-II | 3 (33.3) |

| Wound infection | 2 (22.2) |

| Pelvic collection | 1 (11.1) |

| Clavien-Dindo ≥ III | 0 |

| Perioperative results | |

| Surgical time (minutes) | 245 (203−450) |

| ERAS | 7 (77.7) |

| Postoperative stay (days) | 6 (4−11) |

| Readmission within 90 days | 0 |

| Oncological results | |

| Follow-up time (days) | 1037 (205−2158) |

| Recurrence-free time (days) | 182.5 (79−366) |

| Recurrence | 4 (44.4) |

| Ablation sitea | 1 (11.1) |

| Other liver segmenta | 1 (11.1) |

| Multiple hepaticb | 1 (11.1) |

| Multiple intra/extrahepaticc | 1 (11.1) |

| Re-ablation LM | 2 (22.2) |

| Rescue chemotherapy | 1 (11.1) |

| No rescue | 1 (11.1) |

| Death | 3 (33.3) |

Median (range); Number (percentage).

RLL: right liver lobe; LLL: left liver lobe; CCR: colorectal cancer; ARR: anterior resection of the rectum; MRE: mesorectal excision; ERAS: early recovery after surgery; LM: liver metastases.

As there have been reports of a significantly higher risk of progression of synchronous LM left untreated after resection of the primary tumor,6 it is advisable to assess their simultaneous treatment in certain patients with oligometastatic disease. Although the publications about SUA of LM and CCR resection are very scarce, authors like Lei P et al. have observed that SUA, compared to simultaneous resection, was associated with less blood loss and shorter hospital stay, without negatively influencing the safety of the procedure, survival rates or intrahepatic recurrence.7 It should be noted that local recurrence in the thermal ablation area is relatively low (4.3%).8 In our experience, SUA has been a technically feasible procedure, which does not seem to be associated with a significant increase in morbidity (33% minor complications, not related to the procedure) and which does not seem to negatively affect the oncological results.

We should recognize the limitations of this paper to establish a more generalized recommendation of SUA. The number of patients treated with simultaneous ablation is small, and some cases present a short follow-up. Most publications are retrospective and heterogeneous, as they include patients treated with resection as well as thermal ablation of LM. In addition, it is difficult to propose comparative analyses due to the differences between patients who are selected for simultaneous resection or for SUA. All of this undoubtedly limits the level of evidence.

Since thermal ablation is a curative and less aggressive technique for the treatment of LM, we believe that SUA should be considered in selected cases with high surgical risk due to advanced age, comorbidities, or the need for parenchyma preservation. In these cases, we must accept the possibility of local recurrence in 5%–10% of patients, which could be treated with another percutaneous ablation procedure or surgical resection. In addition, in cases with oligometastatic liver disease, simultaneous SUA for LM provides patients with other benefits, such as reduced hospital stay, lower accumulated morbidity than what a second procedure would entail, and early access to adjuvant therapies.9

Please cite this article as: Perfecto A, Villota B, García JM, Martín I, Gastaca M. Ablación ecoguiada simultánea de metástasis hepáticas sincrónicas y resección del cáncer colorrectal. Serie de casos unicéntrica. Cir Esp. 2024;102:120–122.