We present a series of 146 cases of hepatic trauma (HT) treated in our hospital over a period of 8 years (2001–2008), and comparing it with a previous series of 92 cases (1977–1984).

Material and methodThe mean age in the current series was 28.6 years and the majority were male. The closed traumas were mainly penetrating, with the most frequent cause being road traffic accidents.

ResultsThe American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) classification was used to evaluate the grade of the hepatic injury. Associated abdominal and/or extra-abdominal injuries were seen in 79.5% of the patients, with the most frequent being chest trauma, compared to bone fractures in the previous series. The most common associated intra-abdominal injury was the spleen in both series. The most used diagnostic technique in the current series was abdominal CT. Simple peritoneal puncture and lavage (PLP) were the most used examinations used in the previous series. Non-surgical treatment (NST) was given in 98 cases and the surgery was indicated in the remaining 48. In the previous series, 97.8% of patients were operated on. In the current series, on the 15 patients with severe liver injuries, 5 right hepatectomies, 2 segmentectomies and 6 packing compressions were performed, with the remaining two dying during surgery due to hepatic avulsion. The overall mortality was 3.4%, being 1% in the NST group and 8.3% in the surgical patients. In the previous series, the overall mortality was 29.3%.

ConclusionsThe key factor for using NST is to control haemodynamic stability, leaving surgical treatment for haemodynamically unstable patients.

Presentamos una serie de 146 casos de traumatismos hepáticos (TH) atendidos en nuestro hospital en un periodo de 8 años (2001-2008), comparándola con una serie previa de 92 casos (1977-1984).

Material y métodoEn la serie actual, la edad media fue de 29,6 años, predominando los hombres. Los traumatismos cerrados predominan sobre los penetrantes, siendo la causa más frecuente los accidentes de tráfico.

ResultadosPara valorar el grado de lesión hepática utilizamos la clasificación de la American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST). El 79,5% de los enfermos presentaron lesiones asociadas abdominales y/o extraabdominales, siendo las más frecuentes los traumatismo torácicos vs. las fracturas óseas en la serie anterior. La lesión intraabdominal asociada más frecuente fue la esplénica en ambas series. La técnica diagnóstica más utilizada, en la serie actual, fue TAC abdominal. En la serie anterior, las exploraciones más utilizadas fueron la punción simple y la punción-lavado peritoneal (PLP). En 98 casos se llevó a cabo un tratamiento no operatorio y en 48 restantes se indicó cirugía. En la serie previa, se intervino al 97,8% de los pacientes. En la serie actual, en los 15 pacientes con lesiones hepáticas severas se realizaron 5 hepatectomías derechas, 2 segmentectomías, 6 packing de compresas y los 2 restantes fueron exitus intraoperatorios por avulsión hepática. La mortalidad global fue del 3,4%, siendo del 1% en el grupo TNO y del 8,3% en los pacientes intervenidos. En la serie previa, la mortalidad global fue del 29,3%.

ConclusionesEl factor esencial para utilizar el tratamiento no operatorio (TNO) es controlar la estabilidad hemodinámica del paciente dejando el tratamiento quirúrgico a los pacientes hemodinámicamente inestables.

The liver is the organ that is most affected by penetrating chest traumas, and is the second most affected organ in closed traumas (78%) after the spleen (92.7%), according to the US National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB).1 The most common causes of hepatic trauma are road traffic accidents, accidental falls and violent attacks.2–5 At present, non-surgical treatment (NST) is the treatment of choice for at least 20% of HT that require surgery.6–11 The two main parameters used to predict the need for emergency surgery in HT patients are: the Injury Severity Score (severity >25 points)4 and blood pressure upon admission. The patient's haemodynamic stability on arriving at the emergency department or following initial resuscitation is the main criterion to decide whether NST should be used for a closed HT. The benefits of NST include fewer surgery-related complications, fewer transfusions, a lower infection-related morbidity and a shorter hospital stay.12–14 Mortality in HT is currently between 4% and 15% and depends on the type of injury and injuries related to other extra-abdominal organs.1,3,6,8

The objective of this article is to discuss a recent study with 146 HT patients attended to in our hospital over an 8-year period (2001–2008), comparing it to a previous study15 of 92 cases (1977–1984). It analyses the aetiology, diagnosis, treatment and post-operative morbidity and mortality for the two studies.

Material and MethodOur study includes 146 cases, recorded over an 8-year period. The average age was 29.6±15.2 years compared with 30.3±14.9 years from the previous study.15 Seventy-five percent of the patients was male in both studies.

AetiologyIn the recent study, 139 (95%) cases were closed chest traumas while 7 (5%) were open, 6 being due to a knife wound and one a gunshot wound. Most closed traumas were due to a road traffic accident (68%) compared to other causes. In the previous study,15 90.2% were closed traumas (75% road traffic accidents), whereas 9 (9.8%) were open: 7 due to knife wound and 2 gunshot wounds.

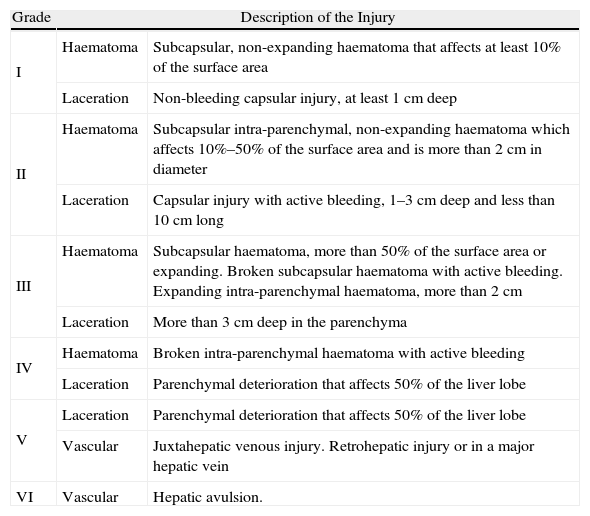

Anatomical Pathology ResultsAt present, the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma-Organ Injury Scale (AAST-OIS) is the most used for grading HT. It has 6 grades, grade I being the least severe and VI being the least compatible with life (Table 1). Injury grading is performed using computed tomography (CT) scan or laparotomy if necessary.1,3–7,10 In the recent study, there were 19 Grade I cases, 57 Grade II cases, 48 Grade III cases, 12 grade IV cases, 8 Grade V cases and 2 Grade VI cases, respectively.

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma-Organ Injury Score.

| Grade | Description of the Injury | |

| I | Haematoma | Subcapsular, non-expanding haematoma that affects at least 10% of the surface area |

| Laceration | Non-bleeding capsular injury, at least 1cm deep | |

| II | Haematoma | Subcapsular intra-parenchymal, non-expanding haematoma which affects 10%–50% of the surface area and is more than 2cm in diameter |

| Laceration | Capsular injury with active bleeding, 1–3cm deep and less than 10cm long | |

| III | Haematoma | Subcapsular haematoma, more than 50% of the surface area or expanding. Broken subcapsular haematoma with active bleeding. Expanding intra-parenchymal haematoma, more than 2cm |

| Laceration | More than 3cm deep in the parenchyma | |

| IV | Haematoma | Broken intra-parenchymal haematoma with active bleeding |

| Laceration | Parenchymal deterioration that affects 50% of the liver lobe | |

| V | Laceration | Parenchymal deterioration that affects 50% of the liver lobe |

| Vascular | Juxtahepatic venous injury. Retrohepatic injury or in a major hepatic vein | |

| VI | Vascular | Hepatic avulsion. |

In the recent study, 94 patients’ (64%) right lobe of the liver was injured and 26 patients’ (18%) left lobe of the liver was injured. The remaining 26 patients (18%) had both lobes injured. However, 65.2% of the injuries were located on the right lobe of the liver in the previous study.15

Related InjuriesIn the recent study, related injuries occurred in 116 cases (79.5%). Extra-abdominal injuries were the most common (70.5%). Among these, chest trauma (54.8%) was the most common, especially pulmonary contusion (32.9%) and rib fracture (25.3%). Splenic injury was the most common related abdominal injury, which occurred in 24 cases (16.4%). In the previous study,15 89.1% of cases had related injuries.

Statistical AnalysisWe performed a descriptive analysis based on the central tendency (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation) in accordance with normality criteria. We also performed a comparative study among qualitative variables using chi-square and Fisher's exact tests, and among quantitative variables using Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test. SPSS® v. 15.0 statistics software was used, and the statistically significant value was P<.05 for all cases.

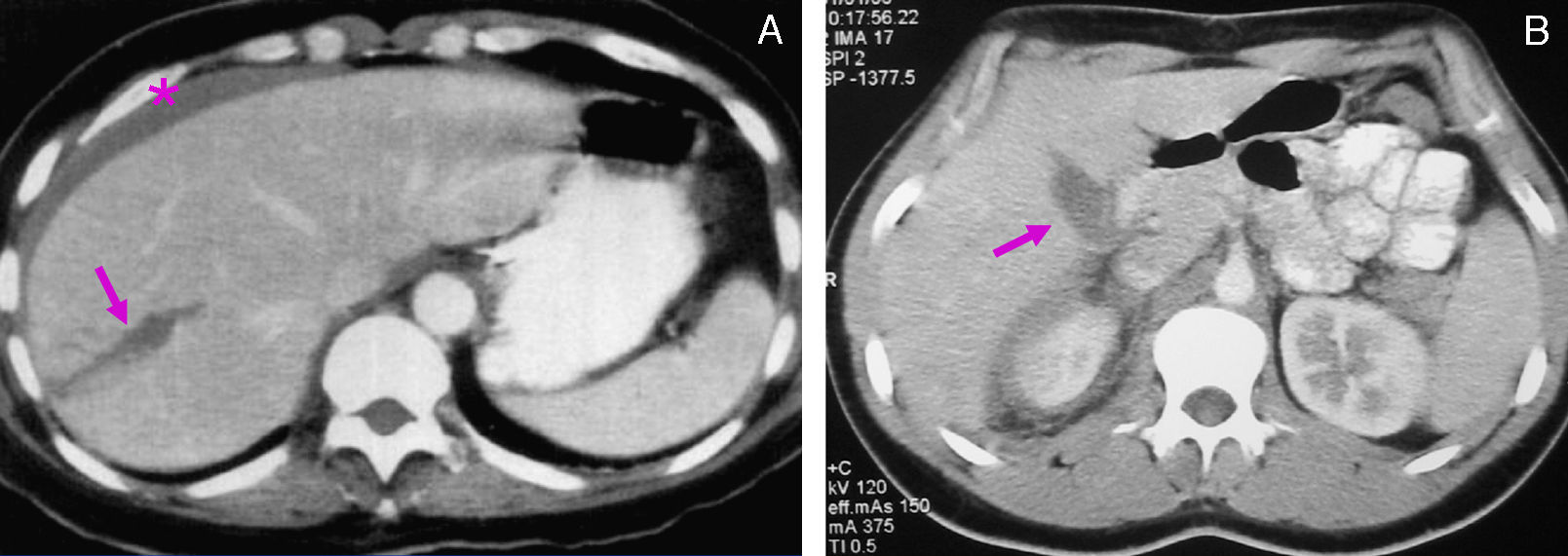

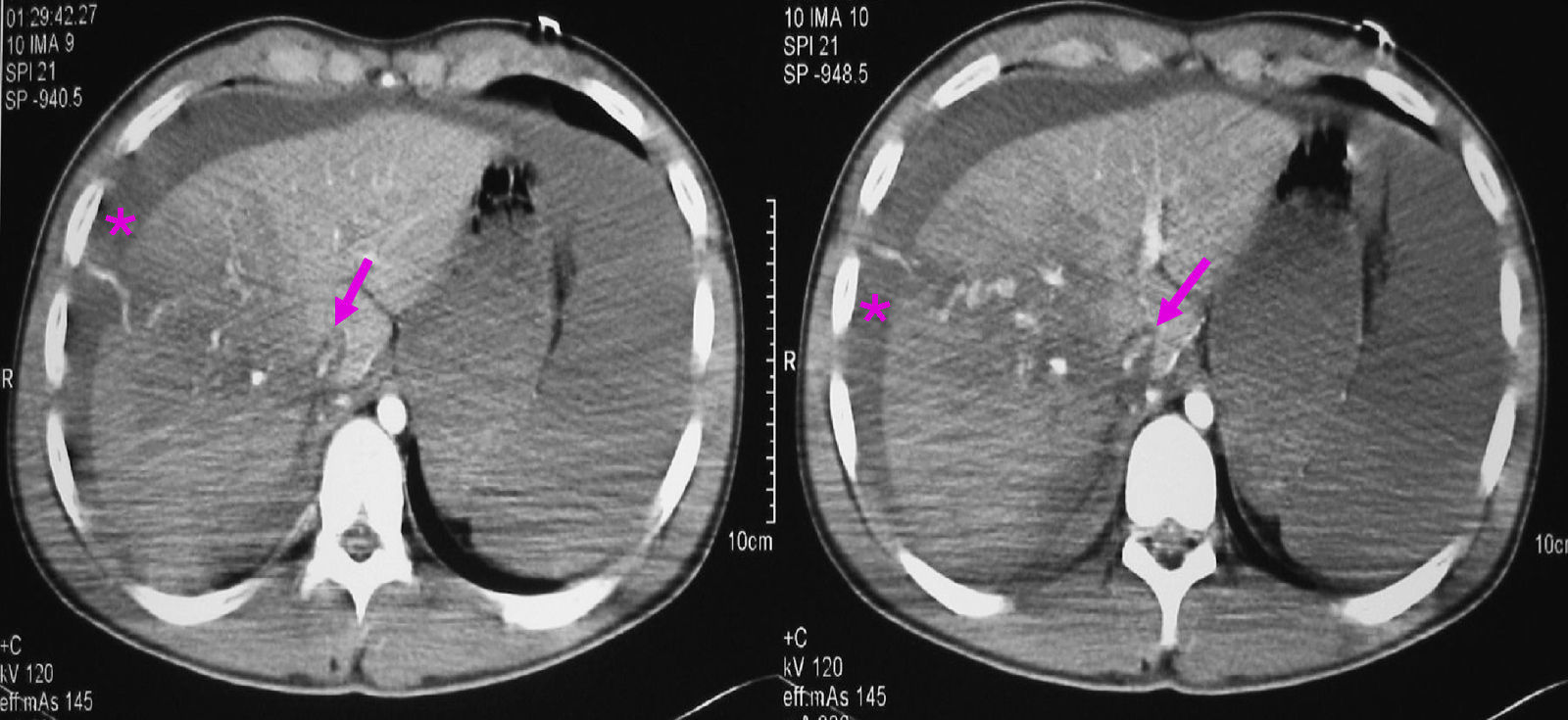

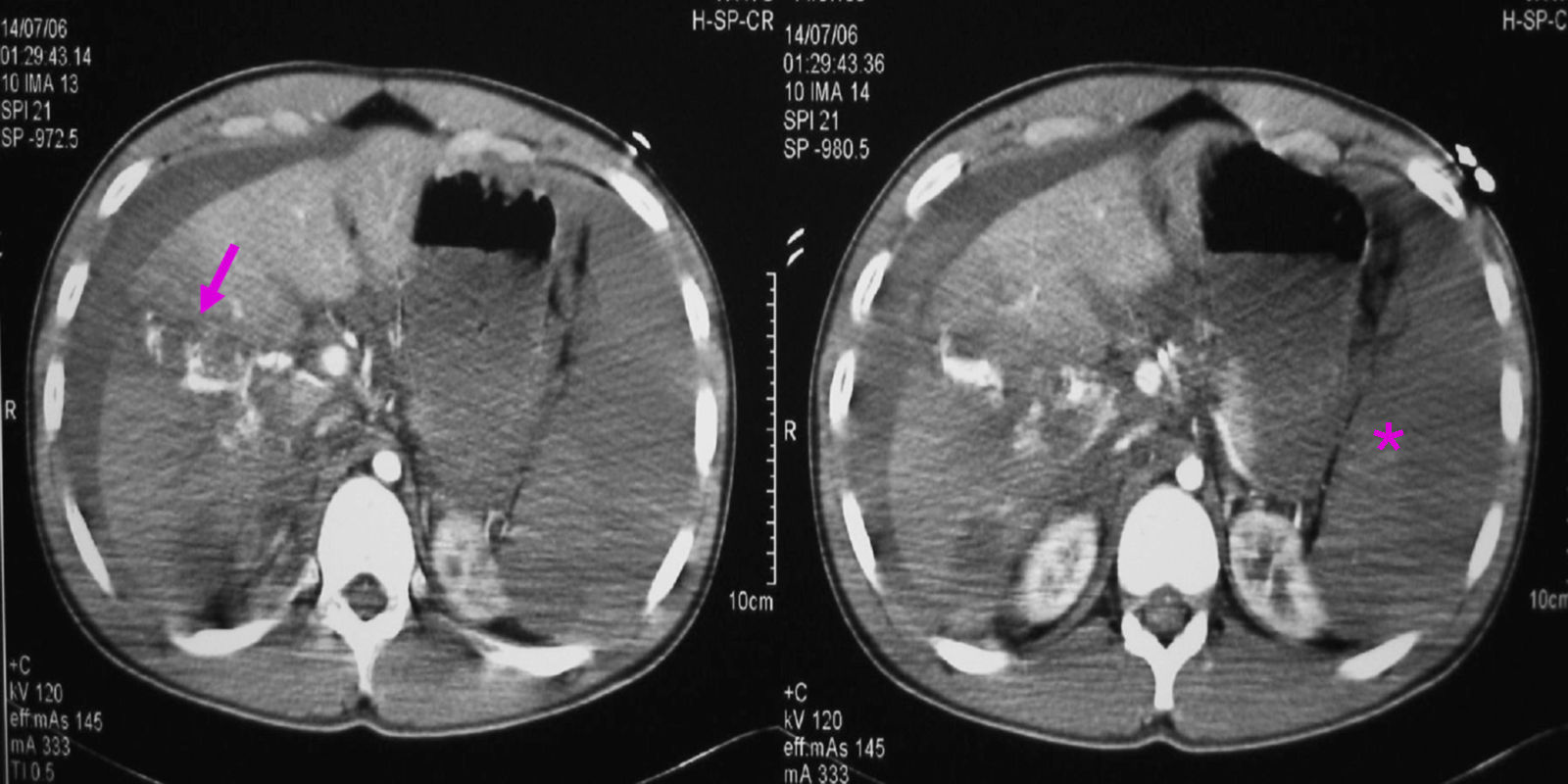

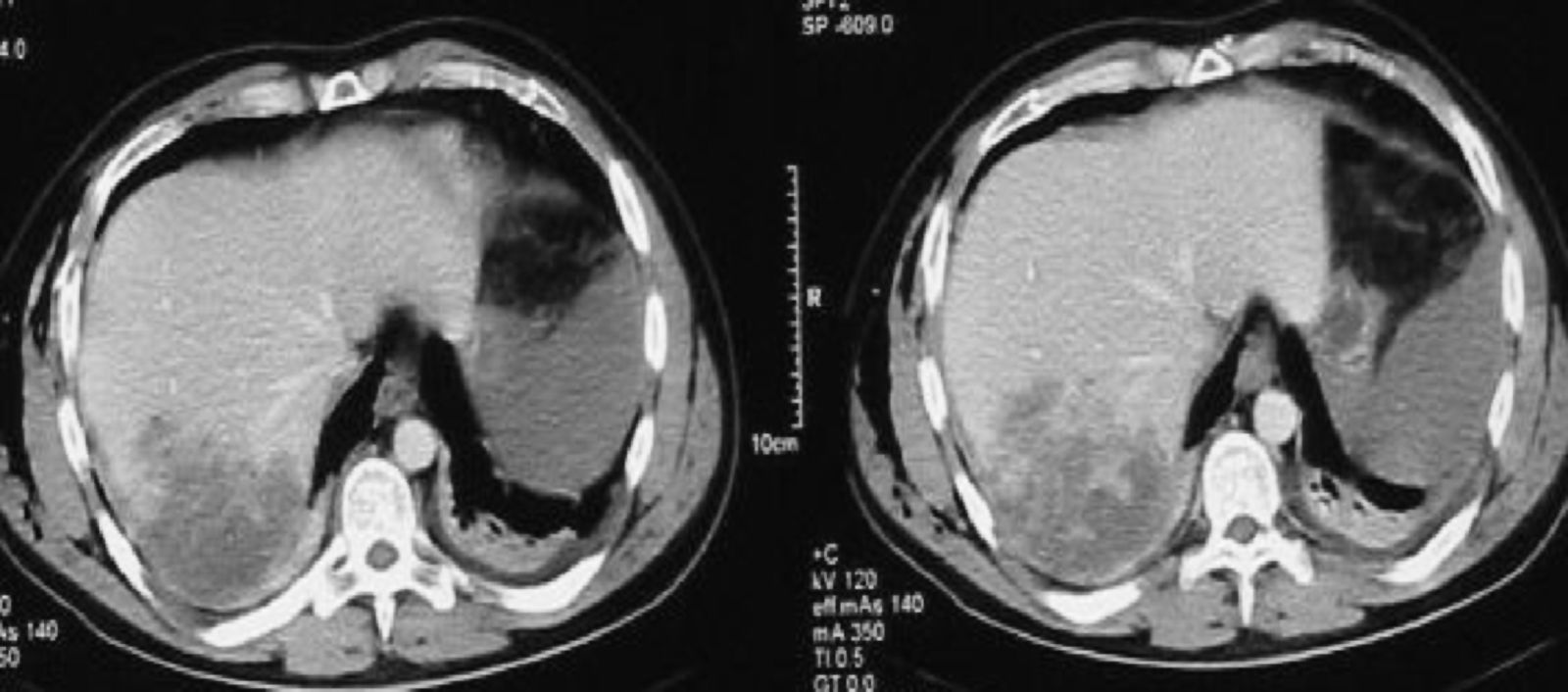

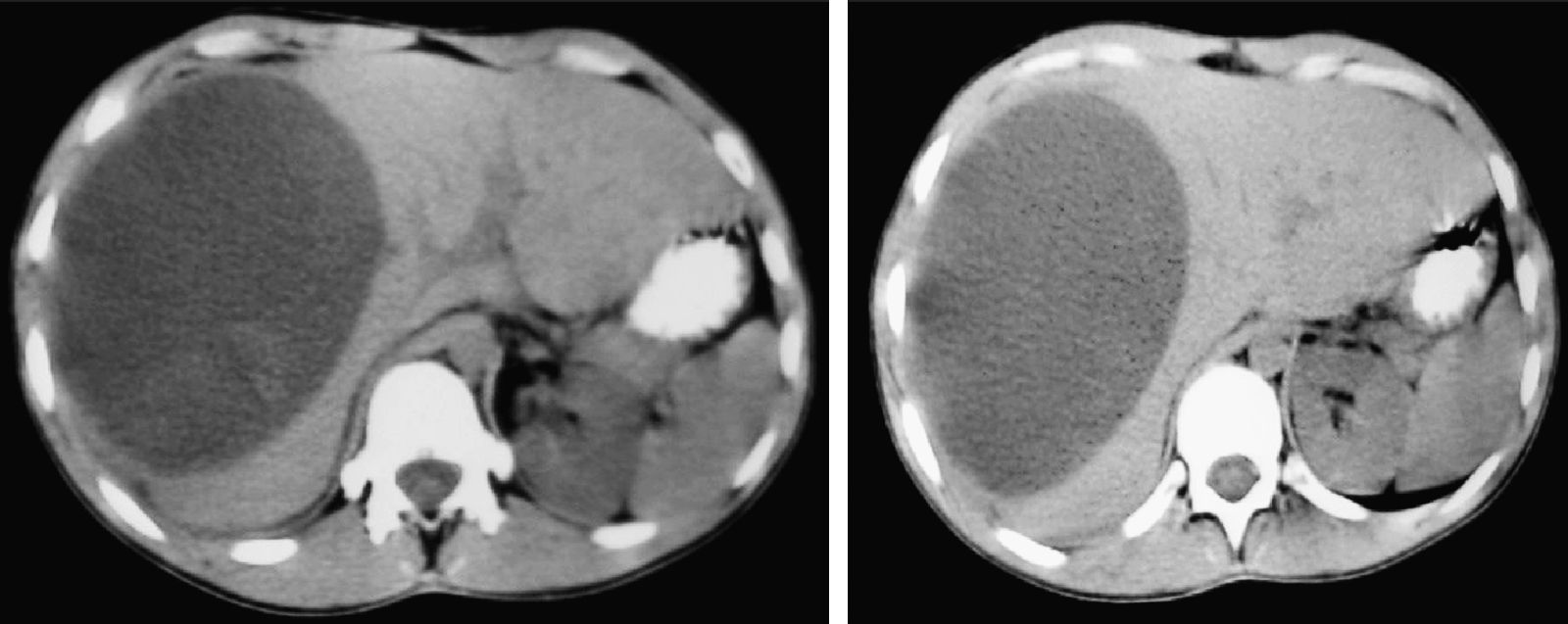

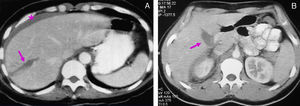

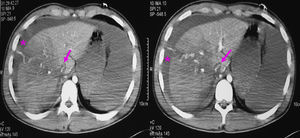

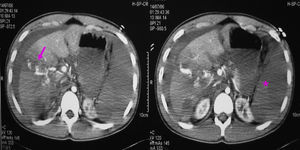

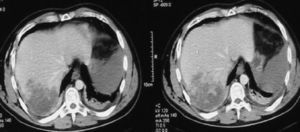

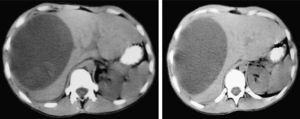

ResultsDiagnosisThe patient underwent the following examinations in the recent study, depending on whether he or she was haemodynamically stable or unstable: (1) 48 patients underwent an abdominal ultrasound: it was the only examination for 5 patients, but for the remaining 43 it was performed before the CT scan; (2) 124 patients underwent an abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast. All cases were haemodynamically stable. From the CT scan, we observed the following: liver lacerations (Figs. 1 and 2), active bleeding with contrast extravasation (Fig. 3), intraparenchymal haematomas (Fig. 4), subcapsular haematomas (Fig. 5), upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding, intrahepatic abscesses, pseudoaneurysms, bilomas, etc.; (3) in 4 cases that were haemodynamically unstable, a peritoneal puncture and lavage were performed (PLP) and all of them were positive, having obtained a bloody fluid from the abdomen. (4) A diagnostic-therapeutic laparoscopy was performed on 3 cases with penetrating injuries caused by knife wounds and 2 closed trauma cases (3.4%), which were haemodynamically stable. Finally, 13 cases (8.9%) did not undergo any imaging tests before surgery: for 10 patients this was due to haemodynamic instability and for the remaining 3 it was because they had penetrating wounds and had directly undergone diagnostic-therapeutic laparoscopy.

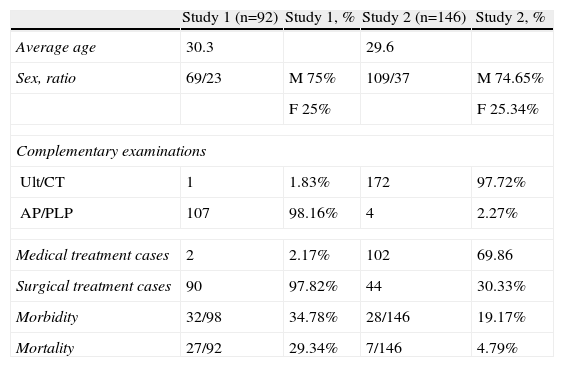

In the previous study,15 the most common examination was the abdominal puncture, as it was performed in 75 of the 92 cases (81.5%) and was positive in 43 cases (57.3%). For the 32 cases that were negative, a PLP was performed that confirmed the diagnosis in 100% of cases. Comparing the 2 studies, we found statistically significant differences (P<.0001) for complementary examinations (Table 2).

Comparative Analysis Between the Two Studies.

| Study 1 (n=92) | Study 1, % | Study 2 (n=146) | Study 2, % | |

| Average age | 30.3 | 29.6 | ||

| Sex, ratio | 69/23 | M 75% | 109/37 | M 74.65% |

| F 25% | F 25.34% | |||

| Complementary examinations | ||||

| Ult/CT | 1 | 1.83% | 172 | 97.72% |

| AP/PLP | 107 | 98.16% | 4 | 2.27% |

| Medical treatment cases | 2 | 2.17% | 102 | 69.86 |

| Surgical treatment cases | 90 | 97.82% | 44 | 30.33% |

| Morbidity | 32/98 | 34.78% | 28/146 | 19.17% |

| Mortality | 27/92 | 29.34% | 7/146 | 4.79% |

In the recent study, 44 of the 146 patients initially underwent surgical treatment and the remaining 102 received an NST. However, 72hours following surgery 4 of the 102 NST patients had to undergo surgery due to related undiagnosed abdominal injuries (3 spleen injuries and 1 duodenal perforation with duodenal-pancreatic injuries). By retrospectively analysing the study, 33% (48 cases) of the 146 cases underwent surgical treatment while the remaining 98 (67%) received NST, including rest, blood product transfusions, repeated clinical examination and control of injuries with abdominal CT scans. In the previous study,15 surgery was indicated for 97.8% of cases with a statistically significant difference compared with the recent study (P<.0001) (Table 2).

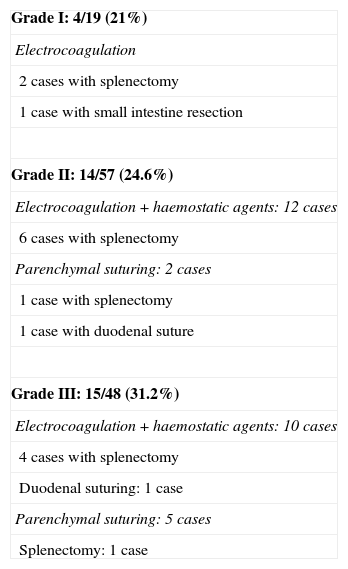

In the recent study, surgery was indicated for 31 cases (21.3%) due to a hepatic injury and for 17 cases (11.7%) because of related abdominal injuries. For 46 cases, a supra-infraumbilical midline laparotomy was performed. In 31.2% of case (15) it was associated with a bilateral subcostal laparotomy, and 2 cases underwent laparoscopy (both penetrating injuries due to knife wounds). Depending on the grade of the hepatic injury, the following surgical techniques were used (Tables 3 and 4):

- (a)

Grade I: of the 19 cases belonging to this group, 4 cases underwent surgical treatment (21%). Surgical indication for 3 of these cases (15.8%) was due to the related abdominal injuries and only on one occasion (5.2%) was this because of the hepatic injury (knife wound). Haemostasis, by means of electrocoagulation, was performed on all hepatic injuries; 2 patients underwent a splenectomy and one patient had an intestinal resection.

- (b)

Grade II: of the 57 patients in this group, 14 underwent surgery (24.6%). Surgery was indicated for 8 cases (14.1%) due to related abdominal injuries, while for 6 patients (10.5%) it was due to the hepatic injury (knife wound for 4 cases, one of which underwent laparoscopy, with electrocoagulation). For 12 cases with HT, haemostasis was performed with electrocoagulation together with a haemostatic agent (Surgicel®, Tachosyl®, etc.), while in the other 2 cases, a simple suture was performed on the injured parenchyma. An associated splenectomy was performed for 6 of the cases undergoing electrocoagulation and for 1 of the patients in which the parenchyma was sutured, while for the other one, the hepatic parenchyma and the duodenum had to be sutured following duodenal-pancreatic injury.

- (c)

Grade III: 15 of the 48 patients in this group underwent surgical treatment (31.2%). On 6 cases (12.4%) surgery was indicated due to related abdominal injuries, whereas for 9 patients (18.8%), surgery was indicated due to the hepatic injury (1 knife wound, which was operated via laparoscopy, with electrocoagulation on the hepatic injury). For 10 cases, haemostasis was performed by means of electrocoagulation with haemostatic agents; 4 cases had to undergo a splenectomy and 1 case had duodenal suture. The other 5 cases underwent parenchymal suturing, and 1 of them needed a splenectomy.

- (d)

Grade IV: 7 of the 12 cases in this group underwent surgery (58.3%). Surgery was indicated for hepatic injury for all 7 cases. Haemostasis was performed on the hepatic injury for 4 cases with simple hepatic parenchymal suturing, although for 1 case liver packing was performed. In the other 3 cases, liver packing was performed, with reintervention after 48hours. For 1 case, the packing was associated with a IVb segmentectomy.

- (e)

Grade V: 6 of the 8 patients in this group underwent surgery (75%). Surgery was due to hepatic injury in all patients. A right hepatectomy was performed in 4 cases, 2 cases underwent associated packing, and for the remaining 2 only liver packing was performed. Reintervention was performed on all patients after 48hours to remove the packing.

- (f)

Grade VI: in this group there were 2 cases, with retrohepatic vena caval injury and right hepatic vein injury, who died in the operating room.

Surgical Treatment.

| Grade I: 4/19 (21%) |

| Electrocoagulation |

| 2 cases with splenectomy |

| 1 case with small intestine resection |

| Grade II: 14/57 (24.6%) |

| Electrocoagulation+haemostatic agents: 12 cases |

| 6 cases with splenectomy |

| Parenchymal suturing: 2 cases |

| 1 case with splenectomy |

| 1 case with duodenal suture |

| Grade III: 15/48 (31.2%) |

| Electrocoagulation+haemostatic agents: 10 cases |

| 4 cases with splenectomy |

| Duodenal suturing: 1 case |

| Parenchymal suturing: 5 cases |

| Splenectomy: 1 case |

n=48/146 (33%).

Surgical Treatment.

| Grade IV: 7/12 (58.3%) |

| Parenchymal suturing: 4 cases |

| With packing: 1 case |

| Packing: 3 cases reintervened after 48 hours |

| With hepatic segmentectomy (IVb): 1 case |

| Grade V: 6/8 (75%) |

| Right hepatectomy: 4 cases |

| With packing: 2 cases |

| Packing: 2 cases reintervened after 48 hours |

| Grade VI: 2/2 (100%) |

| Intraoperative death due to hepatic avulsion |

n=48/146 (33%).

Four patients had gallbladder injuries requiring cholecystectomy: two had grade II-HT, one grade III-HT and one grade IV-HT.

For six of the penetrating hepatic traumas due to knife wounds surgery was performed (85.7%); 2 patients underwent laparoscopy and for 1 laparoscopy was started but was converted to laparotomy for technical problems. In one single gunshot patient (14.3%) a NST was performed. This therapy was chosen because the patient was haemodynamically stable and the imaging tests (CT) showed no peritoneal irritation or related abdominal injuries (especially hollow viscera injury). Furthermore, there were signs of radiological resolution of the hepatic injury during hospital stay, as observed from regular abdominal CT scans.

Postoperative MorbidityIn the recent study, 28 patients suffered complications (19.2%). In the NST group 13.3% of patients had complications (n=13/98) whereas 31.3% (n=15/48) of patients who underwent surgery did. Delayed bleeding was the most common complication, with 12 cases in the whole study (8.2%). The incidence in the NST group was 7.1% (n=7/98); 1 patient had to be intervened, while the 6 remaining cases were treated with conservative treatment. In the surgery group, 10.4% (n=5/48) had bleeding; 4 cases were reintervened and the remaining patient was treated with conservative treatment. Other frequent complications were intra-abdominal abscesses (5 cases; 3.4%) and biliary fistula and/or bilomas (5 cases; 3.4%). Of the intra-abdominal abscesses, 4 cases underwent surgery and 2 cases were resolved with antibiotics, 1 with radiological drainage and the remaining case needed surgical reintervention. Only 1 case (1%) in the NST group had an intra-abdominal abscess, which was resolved with radiological drainage. Biliary fistula and/or bilomas were resolved with radiological drainage.

In the previous study,15 32 of the 92 patients (34.7%) had post-operative complications, with statistically significant differences with the current study (P<.001) (Table 2).

Post-Operative MortalityIn the recent study, overall mortality was 3.4% (5/146 cases), all corresponding with closed trauma (closed trauma mortality n=5/139; 3.6%). None of the penetrating trauma patients died. Mortality for the NST patients was 1% (n=1/98). The cause of death was related extra-abdominal injuries (traumatic brain injury with chest trauma). Mortality was 8.3% (n=4/48) for the surgical treatment group. For 2 cases (4.1%), death was caused by a grade VI hepatic injury, and for the other 2 cases (4.1%) it was due to a related abdominal injury (duodenal-pancreatic injuries).

In the previous study,15 overall mortality was 29.3% (n=27/92 cases) with liver injury being the cause of death for 5.4% of cases (5 patients). There were statistically significant differences (P<.0001) compared with the recent study (Table 2).

DiscussionIn most studies,6,11,13 5% of polytraumatised patients present with HT, mainly males in their twenties and thirties. As reported in our study, the most common cause is road traffic accidents (65%–70%), which is reflected in the literature.1,7,9,10,13–16

To assess hepatic injuries, we used the AAST scale (Liver Injury Scale),4 which has 6 grades of severity. In most studies the most common injuries are grade II, whereas the most severe (grades IV, V, VI) do not reach 10%. In our study, 13% was grade I; 39% grade II; 33% grade III; 8% grade IV; 6% grade V and 1% grade IV. These results are in line with previous studies. Furthermore, our data on related injuries matches those described by most authors.6,9,13,15

At present, the most useful complementary examinations are abdominal ultrasound and CT scans with intravenous contrast. Abdominal ultrasound is the initial imaging test, with 82%–88% sensitivity and 99% specificity to detect intra-abdominal injuries, although precision always depends on the surgeon's experience.12 CT scan is the most sensitive technique to determine the HT's extension and severity3,11,17 and it is the imaging test that provides most information for polytraumatised patients, given that the cranium, chest, abdomen and pelvis, as well as bone, viscera and soft tissue can be seen extremely clearly. The dawn of helical technology has improved resolution, reduced examination time and allowed three-dimensional images to be reconstructed, which is really useful if there is vascular involvement.17 Based on data obtained with the CT scan (false negatives ranges 0%–16% and false positives for liver and spleen injuries 5%), and if the patient is haemodynamically stable, we can choose conservative treatment or NST.4–11 In our study, CT scans were performed on 124 of the 146 patients (84.9%). Fewer diagnostic peritoneal lavage or PLP were indicated, given the advent of more modern imaging techniques. Although detection of intraperitoneal blood has 98% precision, it lacks specificity for the injured organ, which causes many unnecessary laparotomies. In the previous study, however, it was the most used complementary examination technique. At present, it is used when diagnosis is not clear, when the CT scan or ultrasound are unspecific or to rule out intestinal injuries for patients with closed traumas or knife wounds.4,5 In haemodynamically unstable patients, ultrasound or (if not available) PLP are used to detect free fluid in the abdomen, both being more appropriate than CT scans for the initial examination.4,7,15,19 This is because PLP sensitivity and specificity are equal to that of CT, or even better (96% sensitivity compared to 74%).15 Diagnostic laparoscopy is not very useful for closed HT management, but it is mainly indicated to assess intra-abdominal injuries, in stable patients with penetrating traumas caused by knife wounds.4,15,19 However, its use is more controversial for penetrating traumas caused by gunshot wounds. Traditionally, initial treatment has been surgery, but according to recent reporting, conservative treatment could be adopted for up to 28% of cases which are haemodynamically stable and free of related intestinal injuries.3,11,15,18,19 Arteriograms are used to locate active bleeding or when vascular injury is suspected from the CT scan or ultrasound. They also allow us to embolise the bleeding vessel, by placing coils or other haemostatic devices and even, in exceptional cases, perform occlusion using a Fogarty balloon to stabilise the patient before surgery.3,17 Furthermore, they can be used to treat post-traumatic pseudoaneurysms in the viscera if bleeding were to recur.17 In our study, abdominal ultrasound was performed for 48 cases (32.9%) and an abdominal CT scan in 124 cases (84.9%), all with haemodynamic stability. Four (2.7%) haemodynamically unstable patients underwent a PLP. Diagnostic-therapeutic laparoscopy was performed on 5 haemodynamically stable patients, 3 of whom had penetrating trauma caused by knife wounds. Diagnostic or therapeutic preoperative angiography was not performed on any patient, although it was used to treat postoperative complications (post-traumatic intra-hepatic pseudoaneurysms).

NST is based on vast experience achieved by treating children with closed hepatic and splenic traumas.21 Meanwhile, in most cases, the natural evolution of HT is spontaneous haemostasis, since 50%–80% of cases have stopped bleeding when the laparotomy takes place.20 This, together with an elevated morbidity (15%–40%) related to unnecessary laparotomies,20 and given that 77% of patients are haemodynamically stable when they arrive at the emergency department3 suggests that NST should be the first therapeutic choice. At present, NST is the treatment of choice in more than 80% of the studies published with closed hepatic traumas1,3,5–9,12 with a success rate over 90%.6,7,12 However, a NST patient must fulfil a series of selection criteria that consist of the following in most studies3–8,20: (1) the patient must be haemodynamically stable (systolic blood pressure >90mm Hg; heart rate <100 beats/min., normal base excess and lactates) when he or she arrives at the emergency department or following initial resuscitation (≤2000ml fluids, according to the Advanced Trauma Life Support ([ATLS®]); and (2) no signs of peritoneal irritation. Some authors3,7 think that an NST would fail in high-risk patients, which could be identified by a haemoperitoneum of more than 500cm3, age>65 years, pseudoaneurysms or an intravenous radiological contrast leakage. In our study, 98 of the 146 cases (67%) underwent NST, 97 of which had closed traumas, and the other case had a gunshot wound. All cases met the criteria to be included in this group. As per the AAST grading scale, 79% of those that underwent NST (15 cases) were grade I; 75.4% (43 cases) were grade II; 68.8% (33 cases) grade III; 41.7% (5 cases) grade IV; 25% (2 cases) grade V and no case was grade VI. At present, there is controversy concerning the treatment of choice for penetrating HT caused by gunshot wounds. Some authors3,18,22 always use NST when the closed trauma meets the criteria described above for NST: i.e. the patient is haemodynamically stable, has no signs of peritoneal irritation and no hollow viscera injuries. This is supported by the treatment's effectiveness in penetrating traumas caused by knife wounds, together with an elevated incidence of complications that surgical treatment has.3,7,8,11,18,19,22,23 We do not agree with this, and all our patients with knife wounds were submitted to surgical treatment. This is more controversial for penetrating traumas caused by gunshot wounds. The criteria necessary for NST are the same as those described above for closed traumas and knife wounds. Some authors3,11,15,18,19 believe that 30% of isolated liver injuries caused by gunshot wounds (excluding hollow viscera injury by CT) can be treated conservatively in haemodynamically stable patients, and that the role of arteriogram with bleeding vessel embolisation is essential in cases in which contrast extravasation appears on the CT scan.3,18 Only one patient with a gunshot wound received an NST, given that he or she was haemodynamically stable and that the presence of related intra-abdominal injuries was ruled out using the CT scan. The patient evolved satisfactorily and the CT scan showed that the trauma had resolved.

NST failure ranges between 3% and 11% in most studies2,6,10,20 and may be due to the liver injury itself (recurrent bleeding for 40%–50% of cases) or related abdominal injuries which had not been diagnosed previously. In our study, 102 patients initially underwent NST, although 4 patients had to be reintervened, meaning that 98 patients received an NST. Therefore, in our study there was 3.9% of NST failure. This could be explained because the percentage of cases that directly underwent surgical treatment is higher than that in other studies.7,12,20

Surgery is indicated if the patient has haemodynamic shock that does not respond to initial resuscitation with fluid therapy, if NST fails, and in patients with related intra-abdominal injuries subsidiary to surgical treatment.

Immediate haemostasis is essential during surgery, which is often achieved with temporary packing. If hepatic haemostasis is not achieved with packing, the liver hilum is clamped (Pringle manoeuvre). Suprahepatic and/or retrohepatic caval injuries should be suspected if bleeding continues.2–5 Once bleeding is controlled, a decision must be made as to whether the patient should undergo injury repair surgery or damage control surgery (i.e. packing maintenance). This decision depends on how complex the injuries are, the surgeon's experience in hepatic surgery, and the patient's situation. Damage control surgery should be chosen when the surgeon is inexperienced, if the patient has to be referred to another centre for temporary bleeding control, if haemostasis is not achieved with conventional techniques, and if the patient is in a situation of coagulopathy, acidosis and hypothermia. This is because it is a quick and easy technique.2,3,5,6 Focussing on treating injuries, especially those in veins, haemostasis with compression is achieved in most cases and is often controlled by electrocoagulation with an argon scalpel, local haemostasis manoeuvres (clips and sutures) and haemostatic agents.3–5 Profuse arterial bleeding needs haemostatic suture or ligation of vessels.2,6 Haemostasis is achieved for 80%–85% of hepatic injuries using these techniques (generally grade I–II injuries). In the remaining 15%–20%, packing may need to be used, or even in exceptional cases a selective ligature of the relevant hepatic artery should be performed.5 Once bleeding is controlled, debridement should be performed in the areas of necrosis as necessary. Conventional, regulated hepatectomies are not indicated as patients generally have refractory hypovolemic shock with uncontrolled coagulopathy and severe acidosis. It may be indicated when the trauma has almost caused the resection and it is performed by an experienced hepatic surgeon.2–5 For severe hepatic lesions (grade IV–V), including large hepatic veins and retrohepatic caval vein, the technique of choice to control bleeding is liver packing.3,5,9 In fact, patient survival improves the earlier that packing is applied. Liver packing is performed for 4%–8% of cases that need surgery,4,9,12 and in those cases, the abdomen is closed temporarily. Intra-abdominal pressure must be monitored to prevent intra-abdominal hypertension-induced compartment syndrome.3,5 Packing must be maintained 24–48hours to avoid bleeding recurrence, but packing removal should not exceed 72hours, as it has been shown to increase infectious complications. In most studies, a survival rate of 42%–66% has been achieved for hepatic packing of complex liver injuries.3,9 In our study, 48 of the 146 cases (33%) underwent surgical treatment. In 31 cases surgery was indicated due to related injuries (21.3%) and in the remaining 17 (11.7%) due to the hepatic injury.

Postoperative mortality is less than 10% in most studies,1,6–8,10,13,20 where mortality caused by hepatic injuries and for other causes are analysed separately, the former usually being less than 4%. In our study, overall mortality was 3.4% (5 cases); 2 patients died because of a grade VI liver injury (1.4%) and the remaining 3 cases because of related abdominal injuries (2 cases) and extra-abdominal problems (1 case). Mortality was greater in patients who underwent surgery (8.3%; n=4/48 patients) compared to those who received an NST (1%; 1/98).

In summary, HT treatment has changed over the past 30 years, with the systematic surgical approach changing to NST in most cases, reducing postoperative morbidity and mortality. The essential factor for using an NST is to control the patient's haemodynamic stability, leaving surgical treatment for haemodynamically unstable patients.

Conflict of InterestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Bueno F, et al. Cambios en el manejo diagnóstico-terapéutico del traumatismo hepático. Estudio retrospectivo comparando 2 series de casos en periodos diferentes (1997-1984 vs. 2001-2008). Cir Esp. 2011;89:439–47.