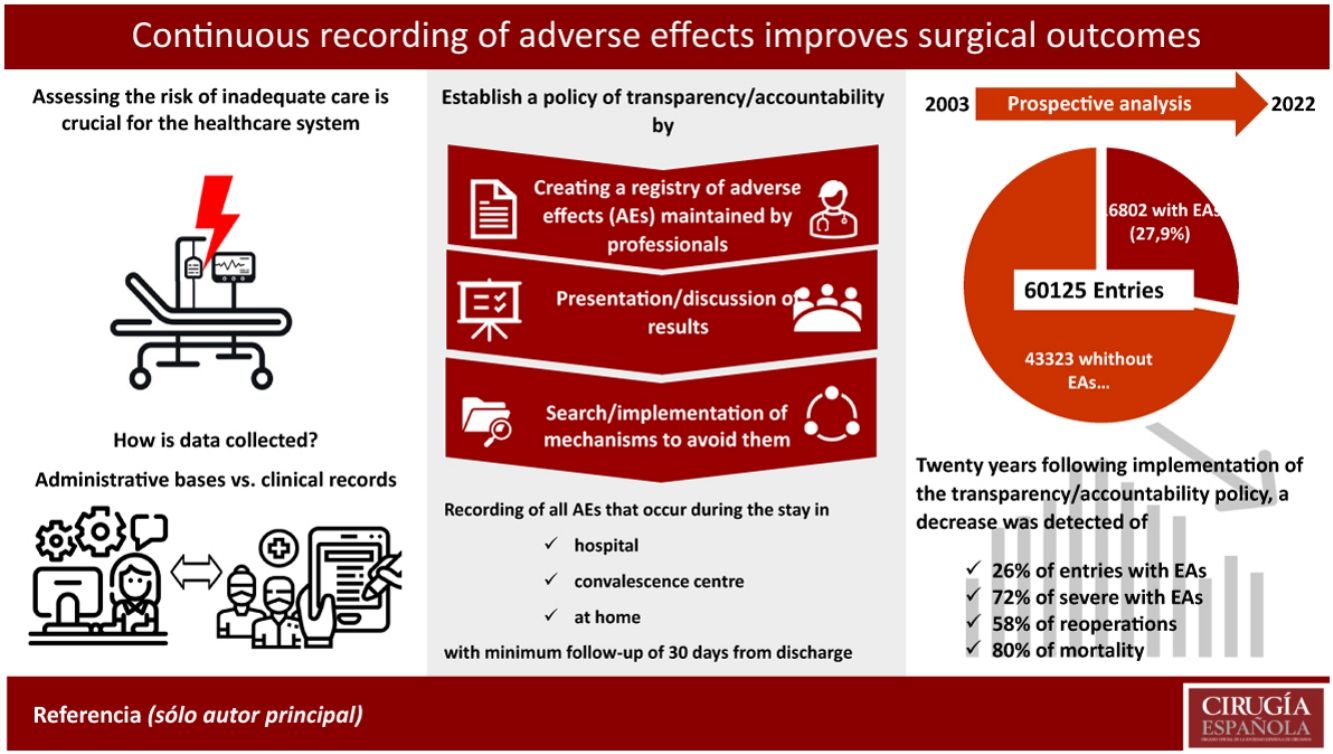

There has been significant debate about the advantages and disadvantages of using administrative databases or clinical registry in healthcare improvement programs. The aim of this study was to review the implementation and outcomes of an accountability policy through a registry maintained by professionals of the surgical department.

Materials and methodsAll patients admitted to the department between 2003 and 2022 were prospectively included. All adverse events (AEs) occurring during the admission, convalescent care in facilities, or at home for a minimum period of 30 days after discharge were recorded.

ResultsOut of 60,125 records, 24,846 AEs were documented in 16,802 cases (27.9%). There was a progressive increase in the number of AEs recorded per admission (1.17 in 2003 vs. 1.93 in 2022) with a 26% decrease in entries with AEs (from 35.0% in 2003 to 25.8% in 2022), a 57.5% decrease in reoperations (from 8.0% to 3.4%, respectively), and an 80% decrease in mortality (from 1.8% to 1.0%, respectively). It is noteworthy that a significant reduction in severe AEs was observed between 2011 and 2022 (56% vs. 15.6%).

ConclusionA prospective registry of AEs created and maintained by health professionals, along with transparent presentation and discussion of the results, leads to sustained improvement in outcomes in a surgical department of a university hospital.

Se ha debatido mucho sobre las ventajas e inconvenientes del uso de bases administrativas o de registros clínicos en los programas de mejora de la atención médica. El objetivo de este estudio ha sido revisar la implementación y los resultados de una política de evaluación contínua, mediante un registro mantenido por profesionales de un Servicio de Cirugía.

Material y métodosSe incluyeron, de forma prospectiva, todos los pacientes ingresados en el Servicio entre los años 2003 y 2022. Se anotaron todos los efectos adversos (EAs) acaecidos durante el ingreso, la estancia en centros de convalescencia o en su domicilio durante un período mínimo de 30 días tras el alta.

ResultadosDe 60125 registros, en 16802 (27,9%) se registraron 24846 EAs. Hubo un aumento progresivo del número de EAs registrados por ingreso (1,17 en 2003 vs 1,93 in 2022) con una disminución del 26% de los registros con EAs (35,0% en 2003 hasta el 25,8% en 2022), del 57,5% en las reoperaciones (del 8,0 al 3,4%, respectivamente), y del 80% en la mortalidad (del 1,8 al 1,0%, respectivamente). Es de remarcar la reducción significativa de los EAs graves observada entre los años 2011 y el 2022 (56% vs 15,6%).

ConclusiónUn registro propectivo de EAs creado y mantenido por profesionales del servicio, junto con la presentación y discusión abierta y trasparente de los resultados, produce una mejora sostenida de los resultados en un servicio quirúrgico de un hospital universitario.

Safety is an essential component of quality care.1 Assessing the risk of inadequate care is crucial for the system, not only in the health dimension, but also the economic, legal, social, and even media aspects involved.2 Interest in adverse effects (AEs) is long-standing, but quantifying them as a way to improve medical care is very recent. In the field of surgery, EA Codman3 is the first reference, who introduced the "End Result Card System" to record symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, complications, and outcomes one year after surgery. Most importantly, however, he included a description of the reasons why the desired results were not obtained and differentiated errors from AEs.3–5 Years later, the American College of Surgeons adopted the system, and it was the origin of the current National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP). Although there is abundant literature on the benefits of adopting this programme in different settings and it has served to develop some indexes and algorithms,6–10 no statistically significant differences have been detected in the percentages of overall complications, serious complications, or mortality between "NSQIP" and "non-NSQIP" hospitals.11,12 Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated a reduction in mortality, complications, and readmissions through registries created and maintained by professionals involved in patient care.13–17 In Europe, there is no common international programme aimed at improving healthcare in surgery, and the data available are scarce, limited in time, and almost always the result of cross-sectional studies conducted by national or regional agencies,2,18–22 on registries that focus on a specific process or AE.23–27

In 2002, our department adopted a registry system that was maintained by our professionals, the results of which were presented and discussed periodically with the intention of improving care outcomes. The purpose of this paper is to describe the development of the system and the results obtained with this policy of continuous evaluation over 20 years.

MethodA longitudinal, prospective study of a cohort of patients admitted to the surgical department of a university hospital. The Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) for quality studies in health care were followed to present the results.28

Data sourceThis study was conducted in xxxx, a healthcare complex serving an area of xxx of about 350000 inhabitants, which includes two acute hospitals (xxx Hospital and xxxx Hospital), a convalescent/long-stay centre (xxxx) and a psychiatric care centre (xxxx) and is affiliated with two universities (xxxxx). The general surgery department admits about 3000 patients/year (45% from the emergency department) and its service portfolio includes any surgical procedure with the exception of solid organ transplantation.

In 2002, it was decided to prospectively collect the AEs that occurred in all patients admitted to the surgical department, regardless of the hospital to which they were admitted and whether or not they required surgery. The collection period included their stay in hospital, in the convalescent/long-stay centre, or at home for a minimum period of 30 days after discharge. Because all health services in the geographical area fall under the health complex and there is a common electronic health record, loss of information is minimal. During the 20 years that the system has operated, there have been two relevant updates: the adoption of the Clavien–Dindo classification in 2011 and the creation of a multidisciplinary database based on Access®, which was activated in 2017.

System operation and data validationA data manager enters all admissions to the department with their administrative data, main diagnosis, and procedure performed into the database on a daily basis. The registry remains active for the stipulated period so that surgeons and nurses can enter all the events they consider appropriate in predefined and mandatory drop-down fields. The system also has a free field, in which the informant can add relevant data to explain the reasons for including the event as an adverse effect and the classify its severity. Once the follow-up period has elapsed, the doctor in charge must close the record, even if no AE has occurred. At this point, an internal reviewer validates the AEs entered. If there are discrepancies, they try to reach a consensus with the informant and if this is not achieved, an external reviewer makes the final decision, which cannot be appealed. Once the validation is completed, the entry, duly anonymised, is incorporated into a database that will allow the generation of periodic reports.

Definition of variablesAn AE was defined as an injury caused by medical management, rather than directly by their underlying disease.29 Given the characteristics of the study, this definition was applied from the moment the patient was admitted to the surgical department, thence to other health institutions or at home, if the AE was a consequence of the same care process.

The percentages of mortality, complications (overall, minor, and severe), reoperations and readmissions were used as quality indices. Mortality was defined as death during the follow-up period, regardless of the cause. Complications were classified according to the Clavien–Dindo classification30 and those with a grade >IIIa were considered severe. Any unplanned surgical procedure to correct a condition not resolved with the index operation or to correct complications of the index operation was considered a reoperation. Unplanned admissions to any hospital facility or emergency department, if longer than 16 h, were entered as readmissions.

Reporting and presentation of resultsIn addition to the classic morbidity and mortality sessions, regular sessions were scheduled to discuss how the AEs evolved and potential improvement actions. Annual reports were also produced for the entire department and for each of its sections. Since 2021, detailed four-monthly reports have been generated by unit and for each of the department’s surgeons.

AuditAn audit was conducted in the last three years (2020, 2021, and 2022) to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the registry data, including a randomly selected 20% of the entries closed without AEs. An internal reviewer analysed all clinical notes, from medical and nursing professionals, laboratory data, and reports of complementary examinations (if any) performed over the stipulated period for potential omissions. If any omissions were found, the above process was repeated to reach a consensus on their inclusion. In addition, a concordance study was conducted between the information provided by the professionals and that defined by the reviewers.

EthicsAlthough the project had been running continuously since 2002, with full knowledge of the hospital structures, the formal approval of the ethics committee was not requested until 2016, at which time, with the help of the IT Service and the Quality Programme, a database in Access format was created and made accessible to the entire hospital network. The ethics committee gave its approval (2016/7042/I) and waived the need to obtain informed consent from patients for inclusion.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were presented as number and percentage. Linear regression analysis was performed for each variable. The kappa index was used to study the concordance of data between informants and reviewers. For the statistical analysis we used R software version 3.5.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)

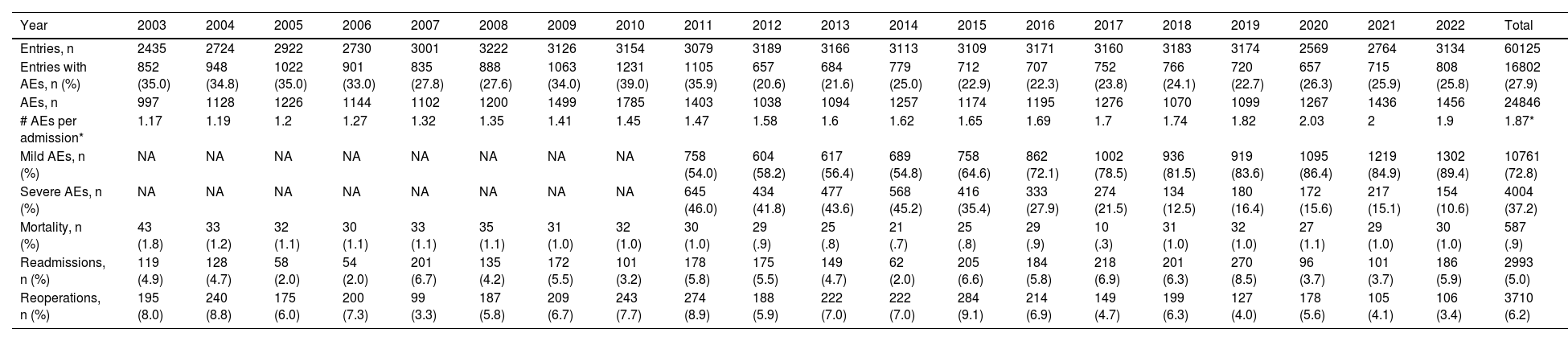

ResultsFrom January 2003 to December 2022, 60125 entries were added to the system. There were 24846 AEs in 16802 admissions (27.9%). The mean number of AEs per admission with AEs was 1.87. In addition, there were 3710 reoperations (6.2%), 2993 readmissions (5.0%), and 587 patients died, representing an overall mortality rate of .9% (Table 1).

Historical evolution of the main results during the period analysed (2003–2022).

| Year | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entries, n | 2435 | 2724 | 2922 | 2730 | 3001 | 3222 | 3126 | 3154 | 3079 | 3189 | 3166 | 3113 | 3109 | 3171 | 3160 | 3183 | 3174 | 2569 | 2764 | 3134 | 60125 |

| Entries with AEs, n (%) | 852 (35.0) | 948 (34.8) | 1022 (35.0) | 901 (33.0) | 835 (27.8) | 888 (27.6) | 1063 (34.0) | 1231 (39.0) | 1105 (35.9) | 657 (20.6) | 684 (21.6) | 779 (25.0) | 712 (22.9) | 707 (22.3) | 752 (23.8) | 766 (24.1) | 720 (22.7) | 657 (26.3) | 715 (25.9) | 808 (25.8) | 16802 (27.9) |

| AEs, n | 997 | 1128 | 1226 | 1144 | 1102 | 1200 | 1499 | 1785 | 1403 | 1038 | 1094 | 1257 | 1174 | 1195 | 1276 | 1070 | 1099 | 1267 | 1436 | 1456 | 24846 |

| # AEs per admission* | 1.17 | 1.19 | 1.2 | 1.27 | 1.32 | 1.35 | 1.41 | 1.45 | 1.47 | 1.58 | 1.6 | 1.62 | 1.65 | 1.69 | 1.7 | 1.74 | 1.82 | 2.03 | 2 | 1.9 | 1.87* |

| Mild AEs, n (%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 758 (54.0) | 604 (58.2) | 617 (56.4) | 689 (54.8) | 758 (64.6) | 862 (72.1) | 1002 (78.5) | 936 (81.5) | 919 (83.6) | 1095 (86.4) | 1219 (84.9) | 1302 (89.4) | 10761 (72.8) |

| Severe AEs, n (%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 645 (46.0) | 434 (41.8) | 477 (43.6) | 568 (45.2) | 416 (35.4) | 333 (27.9) | 274 (21.5) | 134 (12.5) | 180 (16.4) | 172 (15.6) | 217 (15.1) | 154 (10.6) | 4004 (37.2) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 43 (1.8) | 33 (1.2) | 32 (1.1) | 30 (1.1) | 33 (1.1) | 35 (1.1) | 31 (1.0) | 32 (1.0) | 30 (1.0) | 29 (.9) | 25 (.8) | 21 (.7) | 25 (.8) | 29 (.9) | 10 (.3) | 31 (1.0) | 32 (1.0) | 27 (1.1) | 29 (1.0) | 30 (1.0) | 587 (.9) |

| Readmissions, n (%) | 119 (4.9) | 128 (4.7) | 58 (2.0) | 54 (2.0) | 201 (6.7) | 135 (4.2) | 172 (5.5) | 101 (3.2) | 178 (5.8) | 175 (5.5) | 149 (4.7) | 62 (2.0) | 205 (6.6) | 184 (5.8) | 218 (6.9) | 201 (6.3) | 270 (8.5) | 96 (3.7) | 101 (3.7) | 186 (5.9) | 2993 (5.0) |

| Reoperations, n (%) | 195 (8.0) | 240 (8.8) | 175 (6.0) | 200 (7.3) | 99 (3.3) | 187 (5.8) | 209 (6.7) | 243 (7.7) | 274 (8.9) | 188 (5.9) | 222 (7.0) | 222 (7.0) | 284 (9.1) | 214 (6.9) | 149 (4.7) | 199 (6.3) | 127 (4.0) | 178 (5.6) | 105 (4.1) | 106 (3.4) | 3710 (6.2) |

AEs: Adverse effects; NA. Not available; *mean.

Table 1 shows the historical evolution. Briefly, a 26% reduction in AE entries (from 35.0% in 2003 to 25.8% in 2022), a 57.5% reduction in reoperations (from 8.0% to 3.4%, respectively), and an 80.0% reduction in mortality (from 1.8% to 1.0%, respectively) is shown. It should be noted that these reductions are achieved in the context of a higher ratio of AEs per entry, which has increased from 1.17 to almost 2 in recent years. The number of readmissions had been decreasing by 25.5% (from 4.9% to 3.7%) until 2022, but in 2023 there was a rebound to 5.9%. In terms of severity of complications, there is a clear downward trend in severe complications, from 46% in 2011 to 10.6% in 2022.

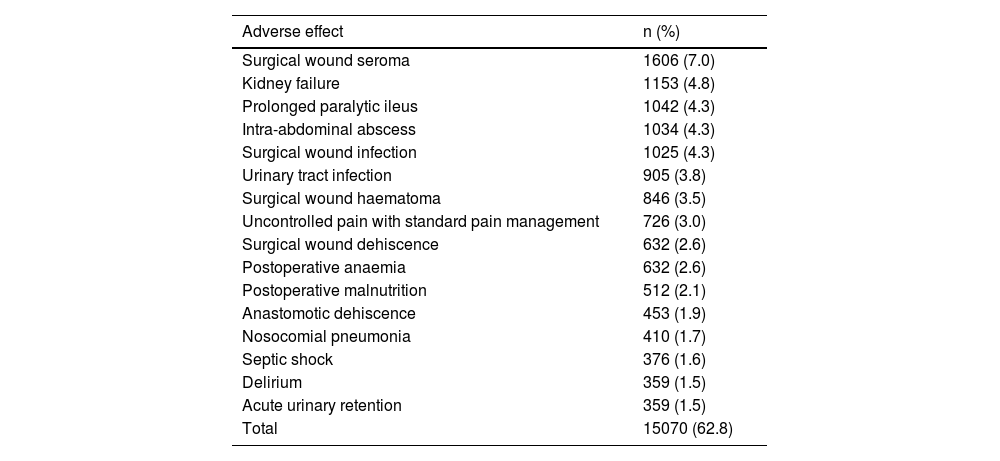

Table 2 shows the most common AEs. The 16 most frequent AEs made up almost 2/3 of the recorded AEs and those related to wounds account for almost 20%.

The 16 most frequent adverse effects among the total of 24846 entered.

| Adverse effect | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Surgical wound seroma | 1606 (7.0) |

| Kidney failure | 1153 (4.8) |

| Prolonged paralytic ileus | 1042 (4.3) |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 1034 (4.3) |

| Surgical wound infection | 1025 (4.3) |

| Urinary tract infection | 905 (3.8) |

| Surgical wound haematoma | 846 (3.5) |

| Uncontrolled pain with standard pain management | 726 (3.0) |

| Surgical wound dehiscence | 632 (2.6) |

| Postoperative anaemia | 632 (2.6) |

| Postoperative malnutrition | 512 (2.1) |

| Anastomotic dehiscence | 453 (1.9) |

| Nosocomial pneumonia | 410 (1.7) |

| Septic shock | 376 (1.6) |

| Delirium | 359 (1.5) |

| Acute urinary retention | 359 (1.5) |

| Total | 15070 (62.8) |

During the years 2020, 2021, and 2022, 1899, 2049 and 2326 entries were closed without AEs, respectively. Therefore, 399, 410 and 466 entries were audited for the years 2020, 2021, and 2022, respectively. In 2020, 52 admissions (13%) with 87 unreported AEs were identified, while in 2021 there were 19 admissions (4.9%) with 23 AEs, and in 2022 63 admissions (13.5%) with 116 AEs. The unreported AEs were mostly mild. The kappa index between the severity of AEs noted by the informants and that validated by the reviewers was .87 (very good).

DiscussionThis study demonstrates that the development and maintenance of an AE registry by surgical professionals, combined with regular reports and open discussion of the results, improves the outcomes of a surgical department in a university hospital.

In our series, 27.9% of admissions had an AE. The percentages of AEs reported in the literature vary between 3.7% and 36.9%, differences that can be explained in some cases by their being retrospective studies, based on administrative bases, with very lax definitions, and in others because they count only one AE (the most serious) per admission or focus on specific procedures or complications.31–37 In our case, this is a prospective database, available in all work areas, with well-defined variables, in which any member of the department, not only surgeons, can enter any incident they consider an AE. It also includes all admissions to the department, elective or emergency, with or without surgery and, if surgery is performed, any regime (major outpatient or inpatient) is considered. Therefore, we believe that our registry is a faithful image of what happens in a surgery department of any university hospital in our country. Even in this context of great thoroughness, the 10 most frequent AEs in our registry coincide with those described by Aguiló et al.38

There is much debate about the source of the data used in studies that analyse surgical outcomes. Administrative databases usually take their data from the hospitals’ cataloguing or billing services; they do it practically automatically, and these databases are those usually used by national agencies, or public or private corporations related to health quality. Some of these databases are certainly not cheap because they require annual fees and require the hospital to have a structure in place to support them. Proponents of administrative databases argue that a large amount of data can be collected in very short periods of time. The registries are usually maintained by professionals, who discuss and define the variables to be entered. As such, they tend to be cheaper and contain more clinical information. In addition, professionals "believe in" and "own" their registry, which is not the case with administrative databases, where their participation is usually little or non-existent and where, in their opinion, important clinical details are omitted. However, most studies have shown a very low degree of concordance when comparing results obtained from administrative databases and clinical registries.39–41 The main criticism of registries is the potential bias of the data entered. Therefore, in our registry there has always been a reviewer who analyses each and every piece of data entered. In addition, in the last three years, an audit has been conducted of all cases closed without AEs and an analysis of the concordance of the severity proposed by the informant and that accepted by the reviewer. The audit has shown that the number of unreported AEs is low and that most are of little clinical relevance.

Some findings deserve some additional mention. The number of entries in the years 2020 and 2021 decreased due to the restrictions that all hospitals, and especially all surgical departments, experienced during the pandemic. This could explain the increase in the number of AEs entered and even a certain increase in mortality. Another remarkable fact is the clear decrease in severe AEs since 2011, when the Clavien–Dindo classification was adopted. This decrease occurred despite the increase in the number of AEs reported per patient. Our perception is that once the occurrence of serious AEs has been resolved (or significantly reduced), other AEs of less clinical significance, but which can be as distressing for the patient as a serious AE, are beginning to be valued.

A noteworthy aspect of our system is the incorporation of all professionals in the open and transparent discussion of the data. These professionals are fully aware of the specific circumstances they face on a daily basis in the hospital and how best to solve problems and improve outcomes. For example, a pancreaticojejunal anastomosis was adopted and standardised to reduce the presence of postoperative pancreatic fistula,42 and a clinical trial conducted comparing open and laparoscopic surgery in cephalic duodenopancreatectomy43; a blood saving programme was implemented in gastric cancer surgery which also led to a reduction in infectious complications, re-operations, re-admissions, and mortality44; a set of measures were applied to reduce surgical wound infections in colon and rectal surgery45 or those associated with venous pathways46; pain control protocols were updated for patients after major outpatient surgery to reduce the number of patients with postoperative pain with a VAS > 347; and protocols for abdominal wall closure were adopted to reduce the incidence of incisional hernia in colorectal surgery by prophylactic mesh use.48

On the other hand, an objective is to reduce the variability of surgery, a well-known but unresolved problem, by disseminating best practices and positive deviance.49,50

This study has a number of limitations that cannot be overlooked. The three most obvious being the long duration of the project, its single-centre nature, and the use in the first instance of an internal reviewer to validate the AEs. The long duration of the project means that a large number of professionals from different backgrounds have been involved over the years, who have launched other initiatives that may have had an influence on the improvement of results and whose weight cannot be individualised. However, these professionals have accepted the project without any reluctance, which has diluted potential personal or hierarchical interference in the identification and classification of AEs. For practical reasons (knowledge and physical and working time availability), the role of reviewer fell to a senior member of the department, with professional ascendancy, aligned with the project's objective and respected by his peers. He is also a member of the hospital's quality committee, with access to other databases to cross-check the data obtained and to propose improvement measures beyond the surgical department. A fourth limitation is that the audit of admissions closed without AEs was performed only in the last three years of the study, which suggests that the incidence of AEs may have been underestimated up to that point. However, it allows us to confirm that the observed decreasing trend in the percentage of AEs is robust. The fifth limitation is that our registry does not have information on the comorbidities of the individual patients. Therefore, it was not possible to perform a study adjusted for these factors. The sixth limitation is that the possibility of preventing AEs is not analysed. Although a scale of the degree of preventability of AEs was used, its evaluation requires a more in-depth analysis that will be the subject of further studies. SIXTH

In conclusion, a registry of AEs created and maintained by professionals, together with regular reporting and open and transparent discussions of outcomes and how to improve them, leads to sustained improvement of outcomes in a general surgery department of a university hospital.

FundingProjectes de Millora de la Qualitat del Parc de Salut MAR. Awarded 23 November 2016. There is no registration number. https://www.parcdesalutmar.cat/media/upload/arxius/programa_qualitat/que_fem/recerca/projectes_estrella/convocatoria%202016/Relacio%20concedits%2016%20doc.pdf.

Authors’ participationLuis Grande, Marta Gimeno, Jaime Jimeno, Manuel Pera, Joan Sancho, and Miguel Pera conceived the idea, designed the study, collected, and analysed the data, and actively participated in the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank all the members of the General Surgery Department of the Parc de Salut Mar for their support and participation in the AE registry throughout the more than 20 years of the project. Without them it would have been impossible to complete the task. In addition, we would like to thank Francesc Cots, MD, PhD, Director of Control and Management of Parc de Salut Mar, and Xavier Castells MD, PhD, and Maria Sala, MD, PhD of the Epidemiology Service and Quality Programme of Parc de Salut Mar for their unconditional support homogenisation of the manuscript data. Finally, we would like to thank Pere Rebassa, MD, PhD and Salvador Navarro, MD, PhD for generously providing the first computer version for data collection and for their role as external reviewers, and Marta Pulido for her editorial assistance.