Peritoneal carcinomatosis remains a condition with poor prognosis and limited therapeutic options. Pressurized intrapertioneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) has been developed as a new tool for delivering intraperitoneal chemotherapy with low morbidity. The aim of this study was to evaluate the initial experience of PIPAC in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis at our hospital.

MethodsA prospective study between January 2019 and February 2020 was carried at a tertiary public hospital. Primary tumor, ascites volume, PCI, chemotherapy regimen, operative time, morbidity, length of hospital stay and mortality were recorded for analysis.

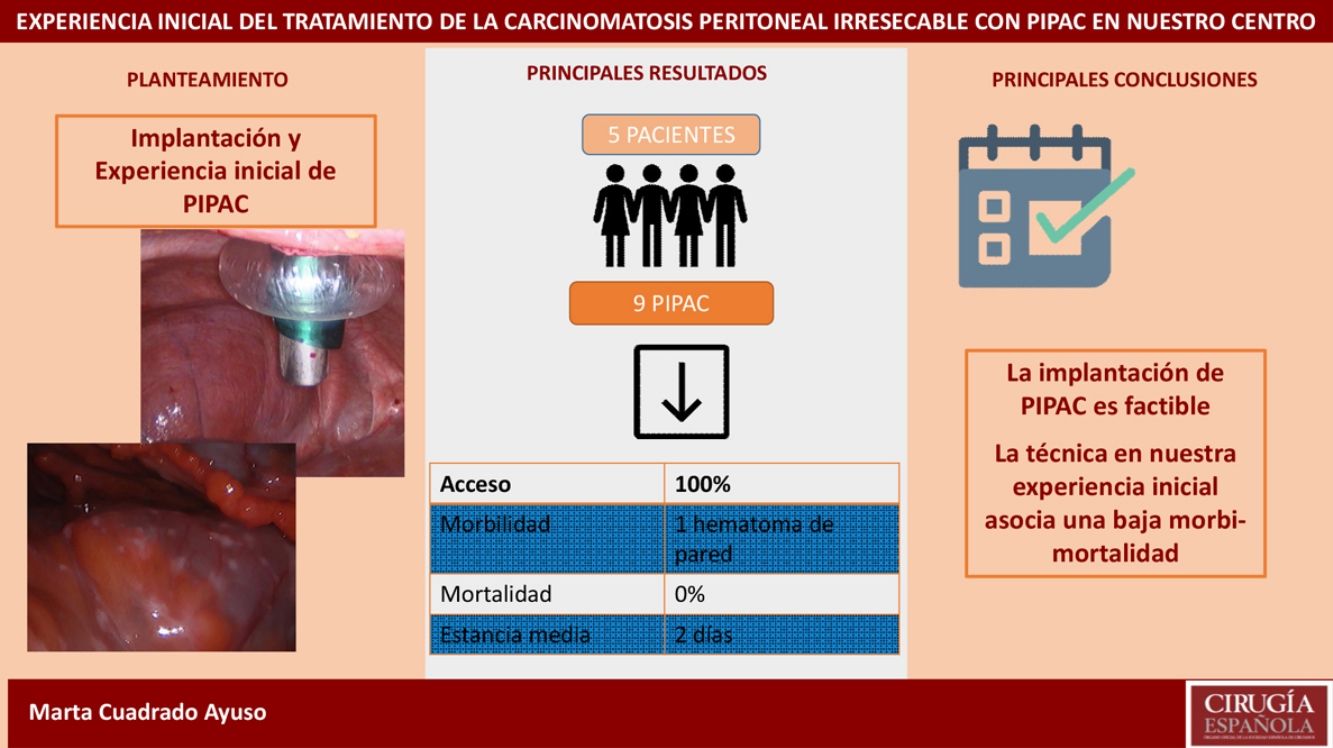

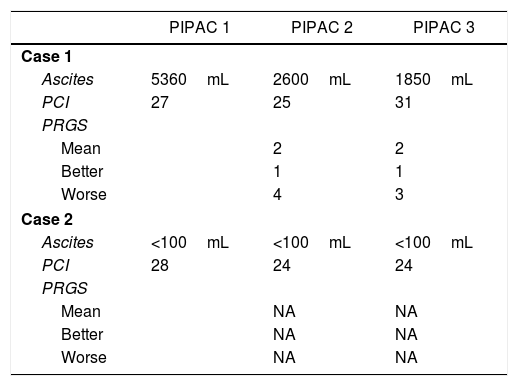

ResultsWe analyzed 9 PIPAC procedures performed in 5 patients. Median PCI was 27.6 (24–35). Median surgical time was 93min (70–125). Only one adverse event occurred out of 9 procedures (Clavien-Dindo II). Median length of hospital stay was 2 days (1–4). Mortality was 0%.

ConclusionPIPAC seems to be a feasible and safe procedure to treat peritoneal carcinomatosis, with low morbidity and short hospital stay.

La carcinomatosis peritoneal se asocia a un mal pronóstico y las opciones terapéuticas son limitadas. El desarrollo de la quimioterapia intraperitoneal presurizada en aerosol (PIPAC) ofrece una alternativa de tratamiento paliativo para estos pacientes con una baja tasa de morbimortalidad. Nuestro objetivo es evaluar la implantación y la experiencia inicial de PIPAC para el tratamiento de la carcinomatosis peritoneal irresecable en nuestro centro.

Material y métodosRealizamos un estudio prospectivo incluyendo todos los pacientes a los que se les realizó PIPAC entre enero de 2019 y febrero de 2020 en nuestro hospital. Se recogieron: el origen del tumor primario, el volumen de ascitis, la extensión de la carcinomatosis peritoneal, el régimen de quimioterapia aplicada, el tiempo quirúrgico, las complicaciones postoperatorias, la estancia hospitalaria y la mortalidad.

ResultadosAnalizamos 9 PIPAC realizadas en 5 pacientes con carcinomatosis peritoneal de origen gástrico, ovárico y neoplasia mucinosa apendicular. La tasa de acceso a la cavidad peritoneal fue del 100%. El PCI medio fue 27,6 (24-35). El tiempo quirúrgico medio fue de 93min (70-125). En nuestra serie solo hubo una complicación Clavien-Dindo II (1/9 procedimientos). La estancia hospitalaria media fue de 2 días (1-4). La mortalidad fue del 0%.

ConclusiónLa implantación de PIPAC en nuestro centro se ha llevado a cabo con seguridad, pudiendo afirmar que es una técnica reproducible y con una baja tasa de morbimortalidad en nuestra experiencia inicial.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis, which is defined as the presence of metastatic deposits in the peritoneal cavity, is a frequent manifestation of neoplasms of different origins: gynecological, gastrointestinal and peritoneal. It is associated with a poor prognosis as well as a poor quality of life due to the frequent appearance of ascites, intestinal obstruction and abdominal pain.1,2

The traditional treatment is palliative systemic chemotherapy, although this is not without side effects. The results obtained are also limited, in part due to the peritoneal–plasma barrier, which makes it difficult for chemotherapy to pass into the peritoneal cavity.3,4

Sugarbaker5 proposed a multimodal treatment combining cytoreductive surgery (CRS) associated with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) with the intention of offering intensive treatment to patients with peritoneal cavity involvement.6 This treatment is indicated in selected patients with determined histologies and limited extension of the disease, with varying PCI limit depending on the origin of the primary tumor, where it has been shown to significantly improve survival.7–10

In 2011, a new technique was developed for the administration of intraperitoneal chemotherapy, known as pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC). Its advantages are a minimally invasive approach, better tissue distribution and penetration of the chemotherapeutic agent, and the possibility of repeating the treatment every 6–8 weeks.11,12

To date, multiple groups have presented good results, with low morbidity and mortality rates associated with the procedure, and the technique has established itself as a palliative treatment option for patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis who are not candidates for treatment with CRS and HIPEC.13–17

Our objective is to analyze the initial results of the implementation of PIPAC for the treatment of unresectable peritoneal carcinomatosis in a public tertiary hospital in the Community of Madrid.

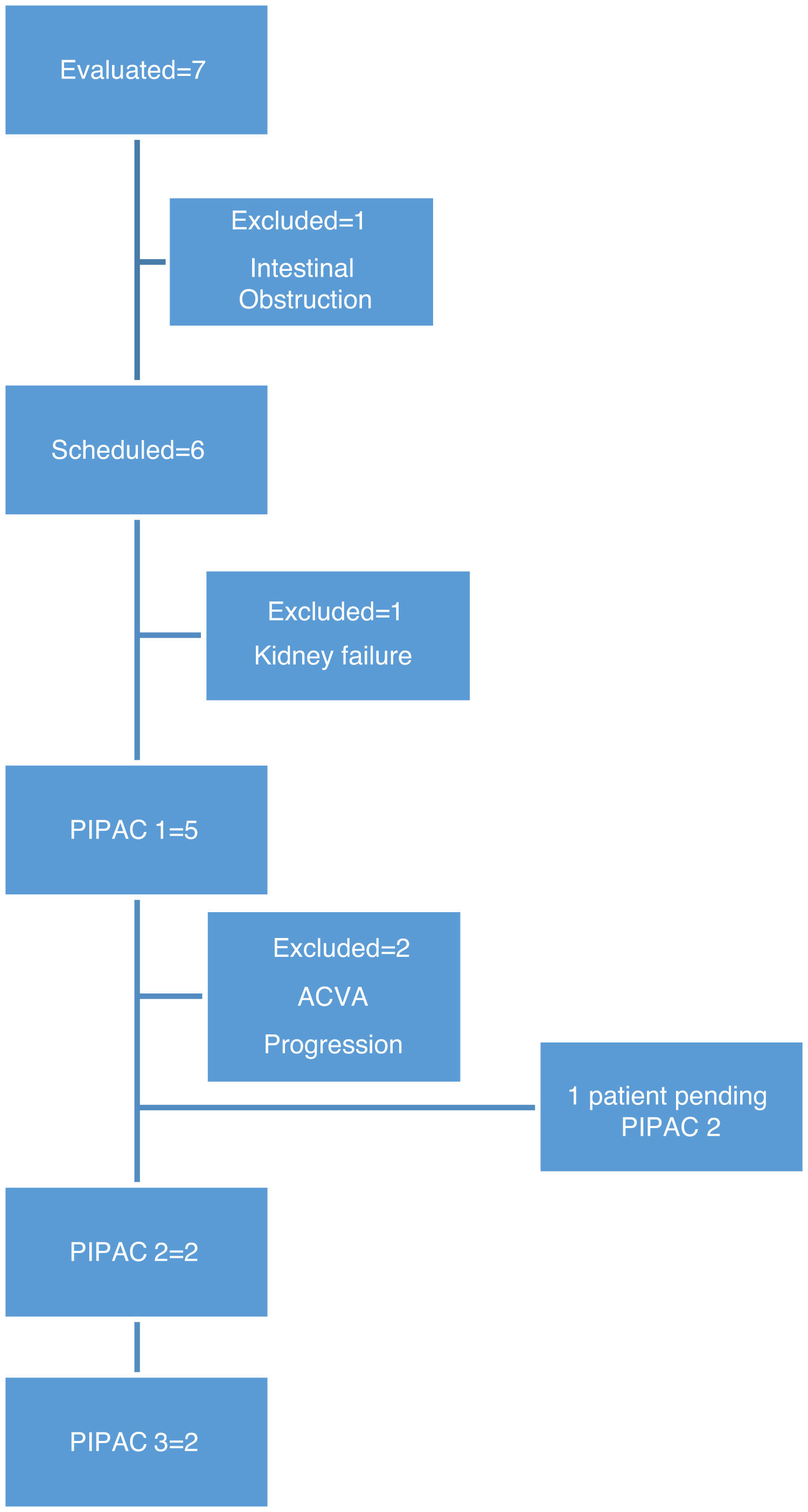

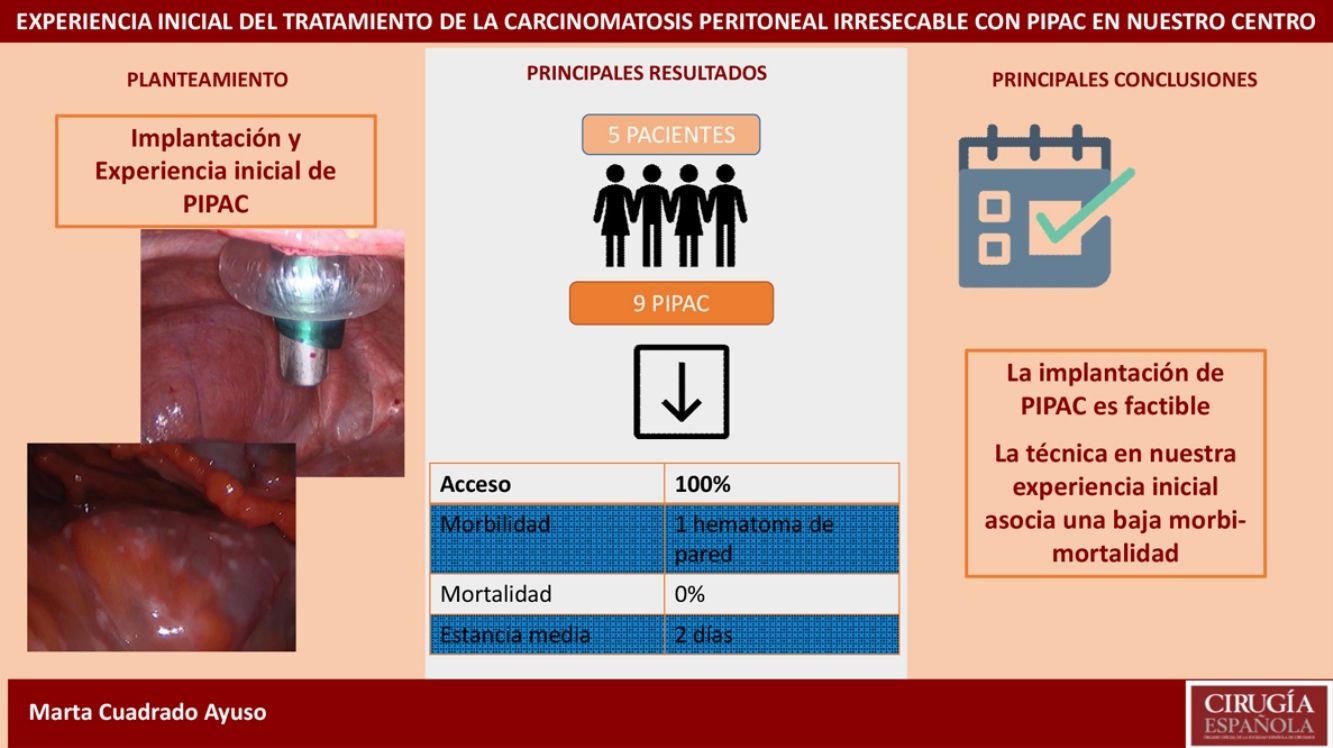

MethodsBetween January 2019 and February 2020, we evaluated 7 patients for PIPAC, all with a diagnosis of peritoneal carcinomatosis (1 ovarian cancer, 5 gastric cancer, 1 appendiceal mucinous neoplasm) and who were not candidates for treatment with CRS or HIPEC.

In this period, we performed 9 procedures with 5 patients. In two patients, it was not possible to administer treatment due to complications prior to treatment: one patient developed end-stage renal failure diagnosed in the preoperative lab work-up, and another patient had intestinal obstruction prior to scheduling the first cycle of PIPAC (Fig. 1).

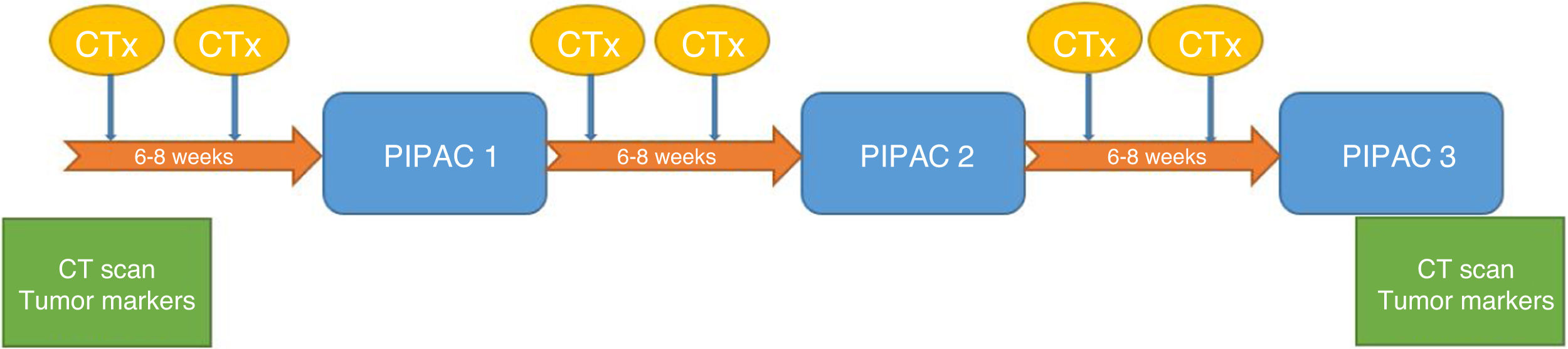

The patients were evaluated by a multidisciplinary committee and subsequently approved individually in the committee for the use of medications in exceptional circumstances. Patients gave their specific informed consent. Three cycles of PIPAC were scheduled for every 6–8 weeks. All patients were administered systemic chemotherapy in the interval following the treatment regimen reflected in Fig. 2.

Based on the experience of other hospitals, and given the absence of data to determine the efficacy of PIPAC treatment but considering it a palliative treatment within the indications, we included in our protocol situations in which there is no therapeutic alternative with proven efficacy, such as: patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal, appendicular, ovarian, gastric or mesothelioma origin, in whom surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy is not indicated due to extensive involvement, in the absence of distant metastases and patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of any other origin in which cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy is not indicated, regardless of the degree of peritoneal involvement. Contraindications include: presence of extraperitoneal metastases, clinical or radiological intestinal obstruction, and perforation of the hollow organs or suspicion of injury during laparoscopic access.

Surgical techniqueAll procedures were carried out by surgeons certified to perform PIPAC. Thromboembolic prophylaxis was administered 12h before the procedure and antibiotic prophylaxis was with 2g cefazolin. Under general anesthesia, pneumoperitoneum was created with a Veress needle in the left hypochondrium in patients with previous abdominal surgeries in whom access to the abdominal cavity could be compromised by adhesions. Ultrasound was used to assess the mobility of the intestinal loops and select the point of insertion of the Veress needle.

When a pressure of 14mmHg was reached, a 5-mm balloon trocar was introduced at the insertion point of the Veress needle, using 5-mm 30° optics for the procedure. The midline was first evaluated for the placement under direct vision of the trocar with a 12-mm balloon. After evacuation and quantification of ascites and a cytology specimen was taken, we systematically explored the peritoneal cavity and determined PCI. Biopsies were taken, with laparoscopic biopsy forceps (4 quadrants whenever possible), leaving the points marked with clips for identification in the successive PIPAC cycles.

With the optics in the 5-mm trocar, the nebulizer (Capnopen®) was inserted so that it remained visible throughout the procedure. The high-pressure injector was connected to the nebulizer, leaving the system covered by a camera cover to prevent accidental spills. The dose of chemotherapy to be administered was verified, and the system was checked for leaks, maintaining the pneumoperitoneum at a stable pressure of 12mmHg with a flow below 0.1mL/s (Fig. 3).

The type of chemotherapy used was doxorubicin 1.5mg/m2 and cisplatin 7.5mg/m2 in all patients, following the protocol. The drug of choice depended on the origin of the primary tumor. Oxaliplatin was indicated for carcinomatosis of colorectal origin, and doxorubicin associated with cisplatin were used in the remaining tumors. Nebulization was started remotely, with all staff leaving the operating room prior to the start of infusion. After nebulization, pneumoperitoneum was maintained for 30min and later evacuated through a closed system connected to 2 filters and the hospital's gas extraction system.

We used a specific checklist prior to the start of chemotherapy infusion in order to detect and minimize errors during the procedure.

Statistical analysisData from all patients were collected prospectively, including the volume of ascites, PCI, biopsy and the appearance of postoperative complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, as well as hospital stay and mortality.

For the statistical analysis, we used the SPSS Statistics version 23 program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL); for quantitative variables, we used the mean and range, and qualitative variables are expressed as absolute value and percentage (%).

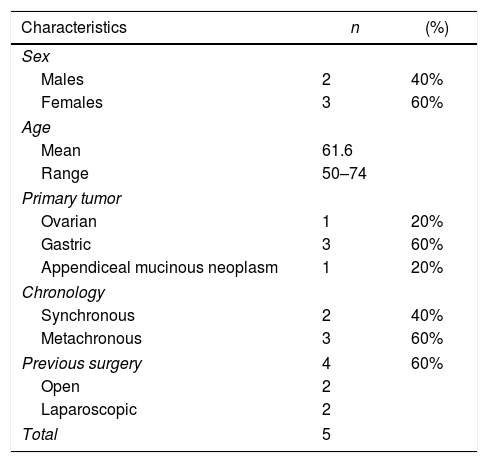

ResultsWe analyzed 9 PIPAC performed in 5 patients. The origin of peritoneal carcinomatosis was gastric in 3 patients (60%), ovarian in one patient (20%), and low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm in one patient (20%). Peritoneal carcinomatosis was synchronous in 2 patients (40%) and metachronous in 3 patients (60%). In 4 of the patients, primary tumor surgery had previously been performed: laparoscopic total gastrectomy in one patient, open total gastrectomy in one patient, laparoscopic appendectomy in one patient, and two CRS in one patient. All patients had received at least one line of chemotherapy prior to the indication of PIPAC.

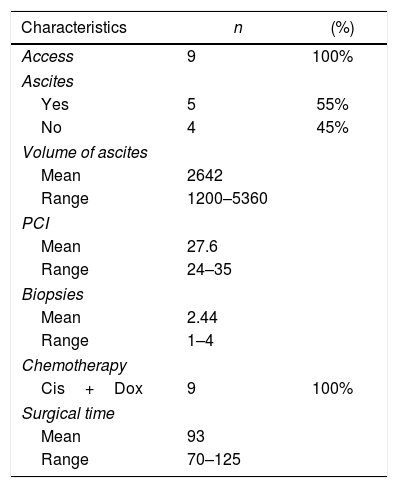

The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Access to the peritoneal cavity was possible in all 9 procedures. In patients with scars from previous surgeries, we used ultrasound to guide access. We found adhesions in patients with previous open surgery, which was more evident in the midline and required the placement of the 12-mm trocar to be displaced. We found no adhesions in patients with previous laparoscopic surgery.

The intraoperative findings and the chemotherapy used are shown in Table 2.

In our series, we recorded a single postoperative complication related to trocar placement: the patient presented anemia on the first postoperative day but no hemodynamic repercussions, requiring transfusion of two units of packed red blood cells and the subsequent appearance of a hematoma on the left flank, which resolved without incident (Clavien-Dindo II). Postoperative mortality (first 30 days) was 0% in our series. Mean hospital stay was 2 days (range 1–4).

Three patients received a single cycle of PIPAC. One patient had an ACVA and functional deterioration, so the second PIPAC was not scheduled. One patient presented lumbar pain, after which CT scan revealed bone metastases; we then decided not to continue treatment due to the progression of extraperitoneal disease. One patient was awaiting further treatment.

Two patients completed 3 cycles of PIPAC, receiving systemic chemotherapy in the intervals of surgery. Table 3 shows the response of the patients who completed the 3 cycles of PIPAC. For one patient, in whom ascites control was achieved, but with no improvement in peritoneal involvement between PIPAC 2 and PIPAC 3, we decided not to continue and maintain systemic CTx. Thirty days later, she presented refractory ascites and HIPEC treatment was administered, which was not effective. A surgical drain was placed for periodic evacuation of the ascites, and survival was 15 months. The second patient, with carcinomatosis originating from a low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm, was initially considered unresectable due to extensive involvement of the small intestine and presented good response with reduction of the small intestine implants. We decided on rescue treatment with CRS and HIPEC, which was carried out 8 weeks after PIPAC 3.

DiscussionPIPAC is a new technique for the laparoscopic administration of intraperitoneal chemotherapy in aerosol form, thereby achieving better distribution of the chemotherapeutic agent and greater tissue penetration.11,18 Also, the possibility to repeatedly administer the treatment enables us to evaluate the tumor response macroscopically in successive laparoscopies as well as histologically by taking biopsies. For this reason, the Peritoneal Regression Grade Score (PRGS) has been developed, which allows us to establish the degree of response in consecutive biopsies.19

In the absence of clinical trials that demonstrate the oncological efficacy of PIPAC in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis,17 and after experiences in other hospitals where the safety of combined treatment, alternating PIPAC with systemic chemotherapy, has been demonstrated, we adopted the proposed treatment scheme in which two cycles of systemic chemotherapy are administered between cycles of PIPAC.20,21 With the combination of both treatments, however, it is difficult to interpret the effect of each one individually. The potential role of PIPAC as a palliative treatment is to control the progression of peritoneal implants, with the theoretical benefit of controlling associated symptoms, ascites, obstruction, etc. This would improve quality of life and may improve the survival of these patients. Given its ability to induce implant regression and, therefore, decrease PCI in some cases, the possibility of using PIPAC as neoadjuvant rescue treatment with CRS and HIPEC has also been described.22

Recent studies show that it is a safe and reproducible technique,23–25 where one of the limiting factors is access to the peritoneal cavity. Most patients who are candidates for PIPAC have had previous abdominal surgeries, and the literature describes an abdominal cavity inaccessibility rate that ranges from 0% to 35%.25 In our experience, access was possible in 100% of the procedures, despite including a high percentage of patients with previous surgeries (80%).

Morbidity in the published series ranges from 0% to 15.9%.14,24–28 Some groups distinguish between complications in the intraoperative period (where the most frequent are small bowel injuries) and in the postoperative period. In our hospital, we did not have any intraoperative complications, and there was only one postoperative complication (Clavien-Dindo II): a hematoma on the left flank related with the insertion point of the 5-mm trocar, which represents a morbidity of 11% due to the small sample size but is consistent with the published literature.

The surgical time has been registered by different groups, with a mean time between 86 and 100min, which is similar to the surgical time in our experience of 93min. This coincidence is probably due to the standardization of the technique as well as the need for surgeon certification prior to the start of the program in the different hospitals.13,15,16

The mean postoperative stay in our series was 2 days, which is one day less than reports by other groups, where the stay was 3 days in both the multicenter study by Alyami et al.14 and in the retrospective analysis by Hübner et al.,25 although this fact is not mentioned in most of the articles published. Due to the good initial experience, the possibility to perform the procedure on an outpatient basis has been suggested,29 which in our experience seems feasible, given that 89% of the patients were discharged 24h after the intervention, and the readmission rate was 0%.

Regarding mortality, rates have been reported in the different series that vary between 0% and 6.85%,14,23 although in these studies the implication of PIPAC as the direct cause of death is debated. In our series, the mortality rate was 0%, including follow-up until the 30th postoperative day.

The limitations of this study are, on the one hand, the small number of patients included: only 7 patients were evaluated for treatment with PIPAC, and in 2 the progression of the disease in the interval before surgical scheduling made treatment impossible. We believe that the lack of clinical trials evaluating the oncological efficacy of PIPAC makes it difficult for this procedure to be incorporated into routine clinical practice. On the other hand, the variability of the origin of the primary tumor, as well as the extension and chronology, all make it impossible to compare or evaluate the response to treatment in our series. To date, only the experience of the first PIPAC procedure performed in Spain has been published,30 so we thought it would be interesting to report our results one year after the implementation of this treatment in our hospital.

We can conclude that the implementation of PIPAC in a tertiary public hospital is feasible. The initial experience at our hospital has shown that it is a safe technique associated with a short hospital stay, although controlled studies are necessary to establish its effectiveness and indications.

Conflict of interestsNone declared.

Please cite this article as: Cuadrado Ayuso M, Cabañas Montero J, Priego Jiménez P, Corral Moreno S, Longo Muñoz F, Pachón Olmos V, et al. Experiencia inicial del tratamiento de la carcinomatosis peritoneal irresecable con PIPAC. Cir Esp. 2021;99:354–360.