In recent years, cultural changes in today's society and improved risk assessment have increased the indication for mastectomies in women with breast cancer. Various studies have confirmed the oncological safety of sparing mastectomies and immediate reconstruction. The objective of this study is to analyze the incidence of locoregional relapses of this procedure and its impact on reconstruction and overall survival.

Patients and methodsProspective study of patients with breast carcinoma who underwent a sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. Locoregional relapses and their treatment and their impact on survival were analyzed.

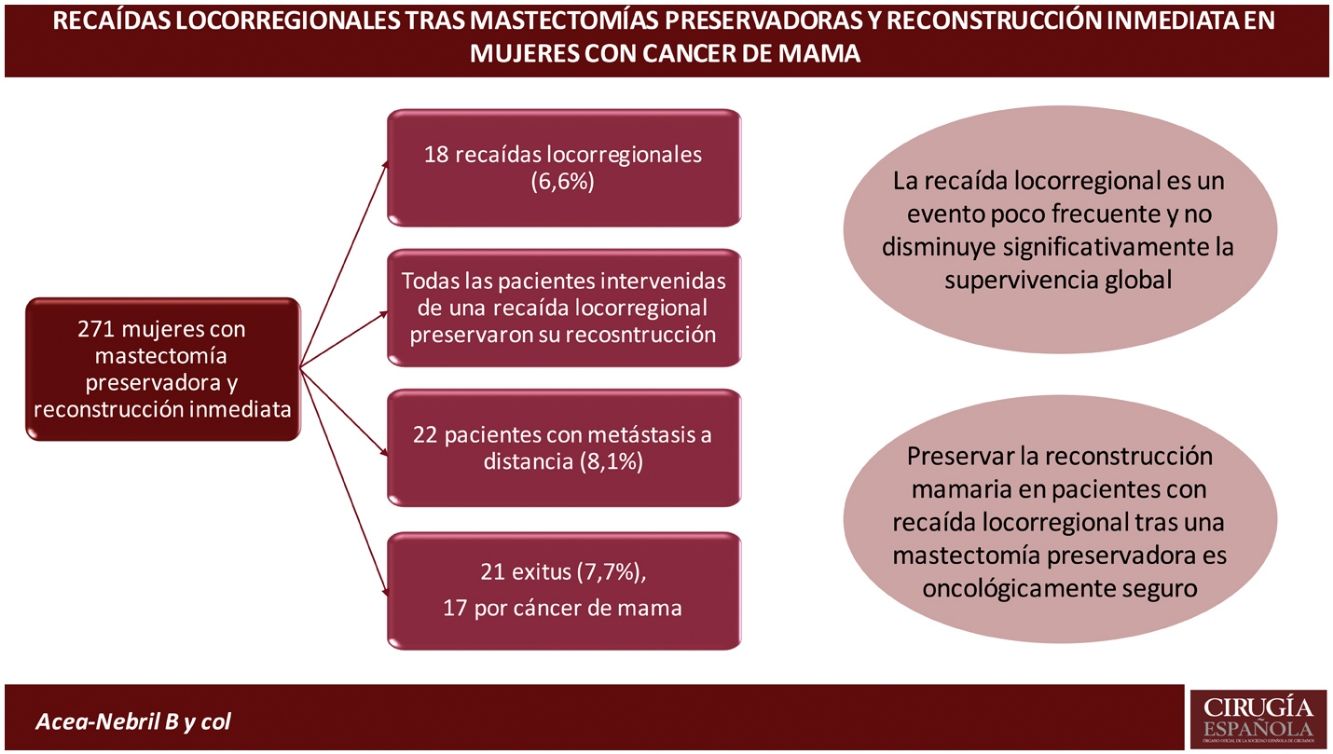

ResultsThe study group is made up of 271 women with breast carcinoma treated with a skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. The mean follow-up was 7.98 years and during the same 18 locoregional relapses (6.6%) were diagnosed: 72.2% in the mastectomy flap and 27.8% lymph node. There were no significant differences in the pathological characteristics of the primary tumor between patients with and without locoregional relapse, although the percentage of women with hormone-sensitive tumors was higher in the group without relapse. Patients with lymph node relapse had larger tumors (80% T2-T3) and 60% had axillary metastases at diagnosis, compared to 7.7% of women with skin relapse (p = 0.047). All patients operated on for locoregional relapse preserved their reconstruction. The incidence of metastases and deaths was significantly higher in patients with a relapse, causing a non-significant decrease in overall survival.

ConclusionLocoregional relapses are a rare event in women with a sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. Most patients with locoregional relapse can preserve their initial reconstruction through local resection of the tumor and adjuvant and / or neoadjuvant therapies.

Durante los últimos años los cambios culturales de la sociedad actual y la mejora en la valoración del riesgo han incrementado la indicación de las mastectomías en mujeres con cáncer de mama. Diversos estudios han confirmado la seguridad oncológica de la mastectomías preservadoras y reconstrucción inmediata. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar la incidencia de recaídas locorregionales de este procedimiento y su impacto en la reconstrucción y la supervivencia global.

Pacientes y MétodosEstudio prospectivo de pacientes con un carcinoma de mama que realizaron una mastectomía preservadora y reconstrucción inmediata. Se analizaron las recaídas locorregionales, el tratamiento de las mismas y la capacidad de preservar la reconstrucción, así como su impacto en la supervivencia.

ResultadosEl grupo a estudio lo constituyen 271 mujeres con carcinoma mamario tratadas mediante una mastectomía ahorradora de piel y reconstrucción inmediata. El seguimiento medio fue de 7,98 años y durante el mismo se diagnosticaron 18 recaídas locorregionales (6,6%): 72,2% en el colgajo de la mastectomía y 27,8% ganglionares. No se evidenciaron diferencias significativas en las características patológicas del tumor primario entre las pacientes con y sin una recaída locorregional, aunque el porcentaje de mujeres con tumores hormonosensibles fue superior en el grupo sin recaída. Las pacientes con recaída ganglionar presentaban tumores de mayor tamaño (el 80% T2-T3) y el 60% tenían metástasis axilares al diagnóstico, frente al 7,7% de las mujeres con recaída en piel (p = 0,047). Todas las pacientes intervenidas de una recaída locorregional preservaron su reconstrucción. La incidencia de metástasis y muertes fue significativamente mayor en las pacientes con una recaída, causando una disminución no significativa de la supervivencia global.

ConclusiónLas recaídas locorregionales son un evento poco frecuente en las mujeres con una mastectomía preservadora y reconstrucción inmediata. La mayoría de las pacientes con recaída locorregional pueden preservar su reconstrucción inicial mediante la resección local del tumor y las terapias adyuvantes y/o neoadyuvantes.

Breast-sparing surgery combined with radiotherapy is the standard treatment for early-stage breast carcinoma.1 Studies2–4 have shown that this therapeutic strategy offers overall survival (OS) similar to modified radical mastectomy (MRM). However, 20%-40% of women with breast carcinoma will require mastectomy.1 There have been three developments in recent years that have led to an increase in the indication for mastectomy.5–8 Firstly, improved risk assessment for breast cancer has increased the indication for mastectomy with immediate reconstruction (IR).8 Secondly, the improved cultural level of society and the availability of information has resulted in many women viewing mastectomy as their best option over conservative management.5 Finally, mastectomy and reconstruction procedures, especially prepectoral reconstruction, have evolved to better cosmetic results, less morbidity, greater patient satisfaction and oncological safety similar to MRM.6,7,9–12

In this context, skin-sparing mastectomies (SSM) or skin- and nipple-sparing mastectomies (SNSM) with IR have become the current standard. However, some of these patients will present with locoregional relapse (LRR) during their follow-up, which poses three challenges for the surgeon. The first is to assess the preservation of the reconstruction and its oncological safety. The second is to select a surgical procedure to suit the reconstructed breast and the disease which, together with adjuvant therapies (radiotherapy, chemotherapy), will ensure locoregional control of the process. Finally, the third is to evaluate the impact of relapse on patient survival in the medium and long term.

The aim of this study is to analyse the incidence of LRR after SSM with IR, the preservation of the initial reconstruction, and the impact of recurrence on long-term OS.

Patients and methodsProspective study of patients with a breast carcinoma who underwent SSM/SNSM and IR between 2008 and 2020 in our centre’s breast unit. Patients with an inflammatory carcinoma or progression during primary systemic therapy (PST) were excluded. All IR procedures were included: implants, muscle flaps and mixed. An analysis was performed of the LRRs and their risk factors, as well as their treatment and impact on OS.

Definitions. LRR was defined as tumour tissue (histologically confirmed) in the chest wall (skin, subcutaneous or muscle) or in ipsilateral lymph node regions. Patients with distant metastases synchronously or prior to diagnosis of LRR were excluded. OS was defined as the time from disease diagnosis to death of any cause. In living patients, OS was defined as the time until the date of the last check-up.

Surgical treatment after diagnosis of breast cancer. All patients were presented to the multidisciplinary committee to decide on the therapeutic plan, based on the relevant clinical guidelines for each period.1,13 The surgeon decided the type of mastectomy and reconstruction, based on the oncological and anatomical criteria of each patient. Intraoperative biopsy of the retroareolar tissue was performed in all SNSMs.

Adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatments after breast cancer diagnosis. Patients with tumours expressing hormone receptors received hormone therapy for five or 10 years. If chemotherapy was required, anthracycline- and taxane-based regimens were used in the main. Trastuzumab was indicated for patients with Her2-overexpressing tumours, and pertuzumab was added in 2017. Radiotherapy was indicated in patients with tumours larger than 4 cm, resection margin involvement and/or axillary metastases. In no case was the internal mammary chain irradiated. In selected cases the multidisciplinary committee decided to only irradiate the chest wall or lymph node chains.

Diagnostic evaluation in patients with LRR. All patients with suspected LRR underwent ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy. After histological confirmation, a thoraco-abdomino-pelvic CT scan was performed to rule out systemic disease and a breast MRI for surgical planning.

Surgical treatment after LRR. Patients with relapse in the mastectomy flap were resected with disease-free margins (no tumour on the stain). In patients with implant reconstruction, resection of the relapse was planned by transcapsular access, i.e., from within the implant cavity to avoid visible scarring. Patients with nodal relapse underwent axillary lymphadenectomy.

Adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatments after LRR diagnosis. All patients received targeted systemic therapy according to tumour subtype. Women with Her2-overexpressing or triple-negative tumours received PST. All patients who had not been irradiated received radiotherapy after excision of the LRR.

Statistical method. Quantitative variables are expressed with their mean, standard deviation (SD), and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Qualitative variables are expressed as proportions and their respective confidence intervals. We used Fisher's exact or χ2 test to find differences between qualitative variables. The student’s t-test for independent groups was used to analyse differences between quantitative variables. If the t-test conditions were not verified, the Mann-Whitney U-test was used. Kaplan-Meier curves and their comparison by logrank test were used for the incidence of LRR and OS.

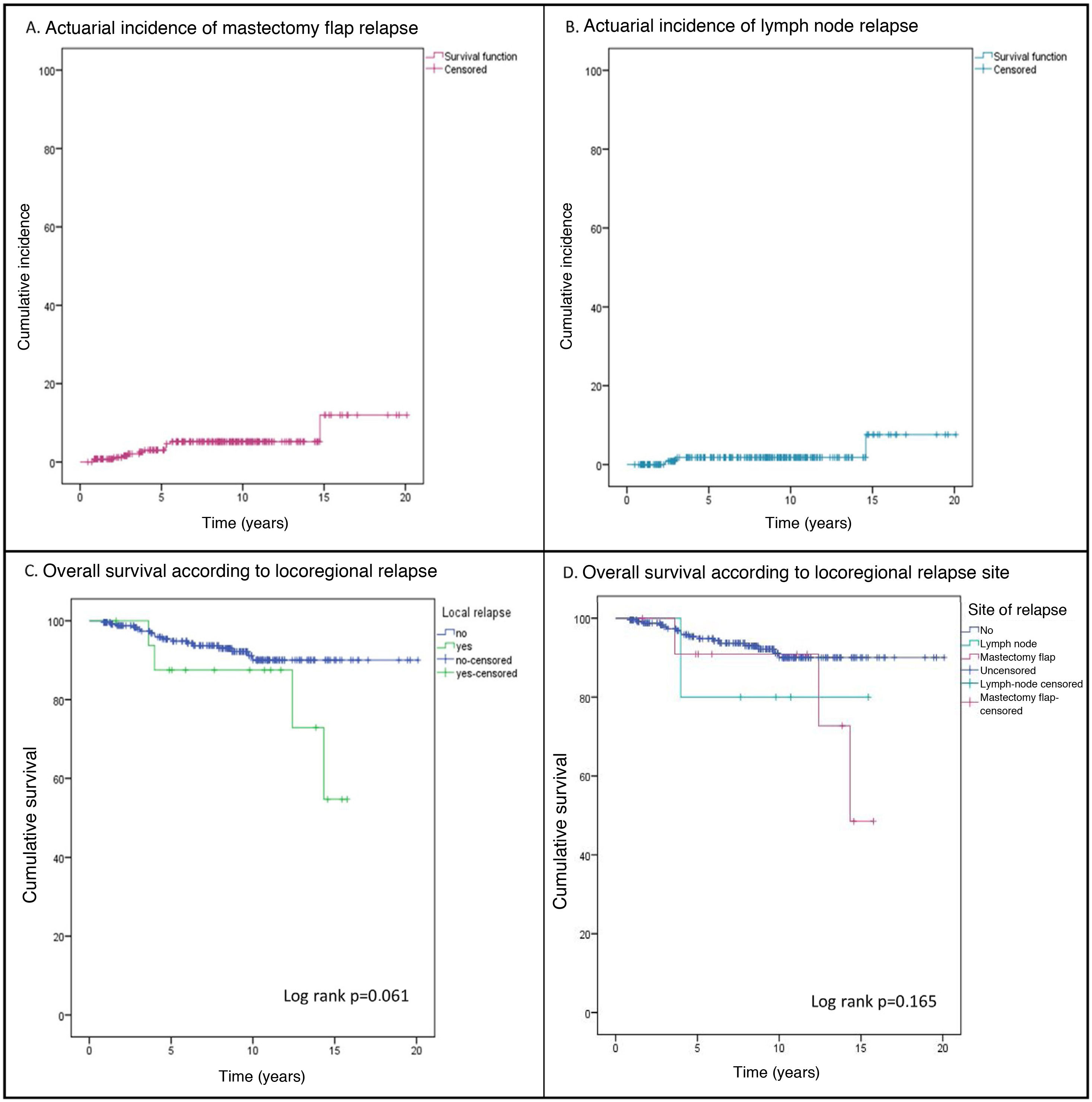

ResultsDuring the study period, 1742 patients were treated, of which 271 constituted the study group (87.5% with infiltrating carcinoma and 12.5% with ductal carcinoma in situ). The mean follow-up was 7.98 ± 4.3 years and during this time, 18 LRRs (6.6%) were diagnosed in 17 patients. Of these relapses, 72.2% were located in the mastectomy flap (13 relapses in 12 patients), with an actuarial incidence at 5 and 10 years of 3.6% (95% CI 2.4%-4.8%) and 5.2% (95% CI 3.7%-6.7%), respectively (Fig. 1Fig. 1A). A total of 27.8% were nodal relapses, with a 5-year actuarial incidence of 1.8% (95% CI .9%-2.7%) (Fig. 1B).

Primary tumour characteristics. Table 1 compares the clinicopathological characteristics between patients with and without LRR. The percentage of patients with a genetic mutation was higher in women with LRR (16.7% vs. 9.1%), this difference was not significant. No significant differences were evident in the pathological characteristics of the primary tumour (histological grade, lymphovascular invasion, size, and tumour subtype), although the percentage of women with hormone-sensitive tumours was higher in the group without LRR (73.2% vs. 52.9%).

Clinicopathological features and complementary treatments

| All n 271 | Locoregional relapse | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n 17) | No (n 254) | |||

| Pathological clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 46.1 ± 8.5 | 44.3 ± 9.8 | 46.2 ± 8.5 | .372 |

| BMI | 24.4 ± 4.1 | 23.5 ± 5.7 | 24.4 ± 4.0 | .250 |

| Genetic mutation | 26 (9.6%) | 3 (17.6%) | 23 (9.1%) | .215 |

| SNSM | 72 (26.6%) | 5 (29.4%) | 67 (26.4%) | 1 |

| Reconstruction type | ||||

| Autologous | 38 (14.0%) | 6 (35.3%) | 32 (12.6%) | |

| Implants | 224 (82.4%) | 11 (64.7%) | 213 (83.9%) | .003 |

| Autologous + implants | 10 (3.7%) | 0 (.0%) | 10 (3.9%) | |

| Bilateral mastectomy | 95 (35.1%) | 8 (47.1%) | 87 (34.3%) | .301 |

| Bilateral tumours | 15 (5.5%) | 0 (.0%) | 15 (5.9%) | - |

| Histological type | - | |||

| IDC | 197 (72.7%) | 13 (76.5%) | 184 (72.4%) | |

| CLI | 33 (12.2%) | 0 (.0%) | 33 (13.0%) | |

| DCIS | 34 (12.5%) | 4 (23.5%) | 30 (11.8%) | |

| Mucinous | 4 (1.5%) | 0 (.0%) | 4 (1.6%) | |

| Papillary | 2 (.7%) | 0 (.0%) | 2 (.8%) | |

| Tubular | 1 (.4%) | 0 (.0%) | 1 (.4%) | |

| Tumour size (cm) | 2.3 ± 2.0 | 2.6 ± 3.0 | 2.3 ± 1.9 | .728 |

| Tumour size | ||||

| T0 in situ | 34 (12.5%) | 4 (23.5%) | 30 (11.8%) | |

| T1mic | 3 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.2%) | |

| T1a | 22 (8.1%) | 3 (17.6%) | 19 (7.5%) | |

| T1b | 34 (12.5%) | 1 (5.9%) | 33 (12.9%) | |

| T1c | 73 (26.8%) | 1 (5.9%) | 72 (28.3%) | .106 |

| T2 | 76 (27.9%) | 4 (23.5%) | 72 (28.3%) | |

| T3 | 17 (6.3%) | 2 (11.8%) | 15 (5.9%) | |

| T4 | 2 (.7%) | 0 (.0%) | 2 (.8%) | |

| Tx | 10 (3.7%) | 2 (11.8%) | 8 (3.1%) | |

| Axillary involvement | ||||

| No | 153 (56.5%) | 9 (52.9%) | 144 (56.7%) | |

| Yes | 106 (39.1%) | 6 (35.3%) | 100 (39.4%) | .044 |

| Not assessable | 12 (4.4%) | 2 (11.8%) | 10 (3.9%) | |

| Axillary lymphadenectomy | 101 (37.3%) | 7 (41.1%) | 94 (37.0%) | .651 |

| Tumour subtype | ||||

| Luminal A | 75 (27.7%) | 2 (11.8%) | 73 (28.7%) | |

| Luminal B Her2- | 82 (30.3%) | 4 (23.5%) | 78 (30.7%) | |

| Luminal B Her2+ | 38 (14%) | 3 (17.6%) | 35 (13.8%) | .241 |

| Her2+ | 18 (6.6%) | 1 (5.9%) | 17 (6.7%) | |

| Triple negative | 24 (8.9%) | 3 (17.6%) | 21 (8.3%) | |

| Not valid | 34 (12.5%) | 4 (23.5%) | 30 (11.8%) | |

| Progesterone receptors - | 93 (34.3%) | 8 (47.1%) | 85 (33.5%) | .069 |

| Hormone receptors + | 195 (71.9%) | 9 (52.9%) | 186 (73.2%) | .071 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 72 (26.6%) | 7 (41.2%) | 65 (25.6%) | .222 |

| High grade | 109 (40.2%) | 8 (47.1%) | 101 (39.8%) | .608 |

| Complementary treatments | ||||

| Primary systemic therapy | 33 (12.2%) | 4 (22.5%) | 29 (11.4%) | .139 |

| Chemotherapy | 189 (69.7%) | 11 (64.7%) | 178 (70.1%) | .647 |

| Radiotherapy to chest wall | 57 (21%) | 1 (5.9%) | 56 (22%) | .116 |

| C radiotherapy lymph nodes | 61 (22.5%) | 2 (11.8%) | 59 (23.2%) | .275 |

| Antibodies | 56 (20.7%) | 4 (23.5%) | 52 (20.5%) | .767 |

| Hormone therapy | 195 (71.9%) | 9 (52.9%) | 186 (73.2%) | .071 |

| Events during follow-up | ||||

| Contralateral cancer | 3 (1.1%) | 0 (.0%) | 3 (1.2%) | - |

| Distant metastasis | 22 (8.1%) | 4 (23.5%) | 18 (7.1%) | .038 |

| Death | 21 (7.7%) | 4 (23.5%) | 17 (6.7%) | .033 |

| Other tumours | 6 (2.2%) | 0 (.0%) | 6 (2.4%) | - |

BMI: body mass index; SNSM: skin and nipple-sparing mastectomy; IDC: infiltrating ductal carcinoma; DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ.

*No surgery was performed for progression during neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Figures in bold represent data with statistically significant differences.

There were no statistically significant differences in the complementary treatments administered in both groups (Table 1). Twenty-one percent of the patients received radiotherapy. Most of the women with LRR (83.3%) did not receive chest wall and/or lymph node chain radiotherapy. However, the incidence of LRR was similar in the irradiated patients (3.3%) to that of the patients who did not undergo radiotherapy (7.1%).

Locoregional relapse characteristics and treatment. No significant differences were detected in the anatomopathological characteristics between the patients with lymph node relapse and those with a mastectomy flap relapse (Table 2). However, patients with lymph node relapse had larger tumours (80% T2-T3) and 60% had axillary metastases at diagnosis vs. 7.7% of women with skin relapse (p = .047). After a mean follow-up of 4.9 years from the LRR procedure, only one patient had another local relapse (10 years after the first relapse).

Clinicopathological characteristics of the initial tumour according to location of relapse

| Locoregional relapse n 18 | Relapse in skin and chest wall n 13 | Relapse in axilla n 5 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis of 1 st tumour | 43.6 ± 9.5 | 44.5 ± 9.5 | 41.2 ± 10.7 | .520 |

| Mean time to relapse (years) | 4.9 ± 4.1 | 4.5 ± 3.8 | 5.1 ± 5.3 | .921 |

| Time of onset | ||||

| <2 years | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | .390 |

| 2-5 years | 10 (55.6%) | 6 (46.2%) | 4 (80%) | |

| >5 years | 6 (33.3%) | 5 (38.5%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Neoadjuvant treatment in relapse | ||||

| Initial tumour type | 3 (16.7%) | 1 (7.6%) | 2 (40%) | |

| DCIS | 4 (22.2%) | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (20%) | 1 |

| DCI | 14 (77.7%) | 10 (76.9%) | 4 (80%) | |

| Tumour size | ||||

| Tis | 4 (22.2%) | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (20%) | .104 |

| T1a | 3 (16.7%) | 3 (23.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| T1b | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| T1c | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| T2 | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (7.7%) | 3 (60%) | |

| T3 | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Tx | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Tumour subtype | ||||

| Luminal A | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (7.7%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Luminal B Her2- | 5 (27.8%) | 4 (30.8%) | 1 (20%) | .543 |

| Luminal B Her2+ | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Her2+ | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (.0%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Triple negative | 4 (22.2%) | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Not assessable | 4 (22.2%) | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Lymph node involvement | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (7.7%) | 3 (60%) | .047 |

| Treatment initial tumour | ||||

| Chest wall radiotherapy | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | - |

| Lymph node chain radiotherapy | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (7.7%) | 1 (20%) | .490 |

| Chemotherapy | 11 (61.1%) | 7 (53.8%) | 4 (80%) | .596 |

| Hormone therapy | 9 (50%) | 7 (53.8%) | 2 (40%) | .618 |

| Anti-Her2 | 3 (16.7%) | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (20%) | .701 |

| Relapse diagnostic method | ||||

| Imaging test | 6 (33.3%) | 4 (30.8%) | 2 (40%) | 1 |

| Palpation | 12 (66.7%) | 9 (69.2%) | 3 (60%) | |

IDC: Invasive ductal carcinoma; DCIS: Ductal carcinoma in situ

Lymph node relapse. Eighty per cent of the lymph node relapses were diagnosed in the first three years (Fig. 1B) and 60% had the same tumour subtype (Table 3). One patient did not undergo surgery for her relapse due to systemic disease progression during PST and died 20 months after the relapse was diagnosed. The remaining four patients underwent axillary lymphadenectomy. All the patients received chemotherapy (primary or adjuvant) and those who had not been irradiated (80%) underwent radiotherapy of the chest wall and lymph node chains.

Characteristics of the patients with lymph node relapse

| Patient A | Patient B | Patient C | Patient D* | Patient E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour type | |||||

| Primary | IDC | DCIS | IDC | IDC | IDC |

| Relapse | IDC | IDC | IDC | IDC | IDC |

| Time to relapse (years) | 14 | 3 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 3 |

| Tumour size (cm) | |||||

| Primary | 4 (ypT2N0) | 4 (pTisN0) | 3.5 (pT2N1) | 8 (ypT3N2) | 2.5 (pT2N1mi) |

| Axillary surgery in primary tumour | Lymphadenectomy | Sentinel lymph node biopsy | Lymphadenectomy | Lymphadenectomy | Sentinel lymph node biopsy |

| Location | |||||

| Primary | UIQ | UOQ right breast | UIQ right breast | UOQ left breast | UIQ |

| Relapse | LD lymph node | Axilla | Rotter | Axilla | Rotter |

| Tumour subtype | |||||

| Primary | Luminal A | - | Her2+ | Luminal B Her2- | Triple negative |

| Relapse | Luminal B Her2- | Her2+ | Her2+ | Luminal B Her2- | Triple negative |

| Adjuvant treatment | |||||

| Primary | nCT + HT | None | CT + Ab | nCT + RT +HT | CT |

| Relapse | CT + RT | CT + RT | CT + Ab + RT | nCT+HT | nCT + RT |

| Time to metastasis (months) | - | - | - | 7 | - |

| Time to death (months) | - | - | - | 20 | - |

Ab: Antibodies; CT: Chemotherapy; DCIS: Ductal carcinoma in situ; HT: Hormone therapy; IDC: Invasive ductal carcinoma; LD: Latissimus dorsi; LIQ: Lower inner quadrant; LOQ: Lower outer quadrant; nCT: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RT: Radiotherapy; UIQ: Upper inner quadrant; UOQ: Upper outer quadrant.

Mastectomy flap relapse. There was no relapse in the nipple-areola complex (NAC). The mean time to relapse was 4.9 years (± 3.8) (Fig. 1A). Most relapses (83.3%) had a different tumour subtype to the initial tumour (Table 4). One patient did not undergo surgery due to systemic disease progression during PST. The reconstruction of all the patients who underwent surgery was preserved. The patients who did not receive radiotherapy were irradiated.

Characteristics of patients with relapse in skin flap

| Patient F | Patient G | Patient H | Patient I | Patient J | Patient K | Patient L | Patient M | Patient N | Patient O | Patient P | Patient Q | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour type | ||||||||||||

| Primary | IDC | IDC | IDIS | IDC | IDC | IDC | DCIS | IDC | IDC | IDC | DCIS | IDC |

| Relapse | IDC | IDIS | IDC | IDC | Tubular | IDCIDC | IDC | IDC | IDC | IDC | IDC | IDC |

| Time to relapse (years) | 14.7 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 2.910 | 2.6 | 2.1 | .8 | .9 | 3.7 | 5.3 |

| Tumour size (cm) | ||||||||||||

| Primary | 3 (pT2N0) | .5 (pT1aN0) | 1.5 (pTisNx) | 0 (ypTxN0) | 1 (pT1bN1) | .2 (pT1aN0) | 2.5 (pTisN0) | .4 (pT1aNx) | 3.2 (pT2N0) | .2 (ypT1aNx) | 4 (pTisN0) | .9 (pT1bN0) |

| Relapse | 1 (pT1b) | 1 (pTis) | 1 (pT1a) | .5 (pT1a) | .5 (pT1a) | 1.1 (pT1c).5 (pT1a) | .5 (pT1a) | 1.4 (pT1c) | 1 (ypT1b) | .5 (ypT1aN2) | .9 (pT1b) | |

| Location | ||||||||||||

| Primary | UIQ | LOQ | LOQ | LOQ | LIQ | LIQ | UIQ | Retroareolar | UIQ | LOQ | UOQ | UOQ |

| Relapse | UIQ | UIQ | UOQ | UIQ | LIQ | LIQ/LOQLIQ/LOQ | UIQ | UOQ | UIQ | LOQ | UOQ | UOQ |

| Tumour subtype | ||||||||||||

| Primary | Luminal B Her2- | Luminal B Her2- | - | Luminal B Her2+ | Luminal B Her2- | Luminal B Her2+ | - | Triple Negative | Luminal A | Triple Negative | - | Luminal B Her2- |

| Relapse | Luminal B Her2- | - | Her2+ | Luminal B Her2- | Luminal A | Triple NegativeTriple Negative | Luminal B Her2- | Luminal B Her2+ | Luminal B Her2- | Luminal B Her2- | Luminal B Her2- | Luminal B Her2- |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||||||||||

| Primary | CT + HT | CT + HT | None* | nCT + Ab+HT + RT | HT | CT + Ac +HT | None | None | CT+HT | nCT | - | None*** |

| Relapse | CT + HT + RT | RT | CT + Ab | CT + RT+HT | RT + HT | CT + RTCT | RT + HT | CT + Ab** | CT+HT + RT | nCT + RT | nCT + RT +HT | Ct + RT +HT |

| Time to metastasis (months) | - | - | - | 56 | - | - | - | 23 | 27 | - | - | - |

| Time to death (months) | Alive | Alive | Alive | 30 | Alive | Alive | Alive | 114 | 33 | Alive | Alive | Alive |

Ab: Antibodies; CT: Chemotherapy; DCIS: Ductal carcinoma in situ; IDC: Infiltrating ductal carcinoma; LIQ: Lower inner quadrant; LOQ: Lower outer quadrant; HT: Hormone therapy; nCT: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RT: Radiotherapy; Sx: Surgery. UIQ: Upper inner quadrant; UOQ: Upper outer quadrant.

Events and survival. During follow-up, 22 patients (8.1%) developed distant metastases, a higher incidence than locoregional relapses (6.6%). Twenty-one women (7.7%) died during follow-up (Table 1), 17 (6.3%) from their breast carcinoma, three (1.1%) from another tumour, and one patient (.4%) with bone metastases died of medical causes. Three patients with metastases were alive at the end of follow-up. OS and disease-free survival at 10 years were 88.9% (95% CI 86.3%-91.5%) and 80.4% (95% CI 77.1%-83.7%), respectively. The incidence of metastases (23.5% vs. 7.1%; p = .038) and deaths (23.5% vs. 6.7%; p = .033) was significantly higher in patients with LRR (Table 1), resulting in a non-significant decrease in 10-year OS (87.5% [95% CI: 79.2%-95.8%] vs. 90% [95% CI: 87.5%-92.5%]; p = .061 [Fig. 1C]). All patients with LRR and distant metastases died during follow-up. There was no significant difference in OS according to type of LRR (Fig. 1D).

DiscussionSparing mastectomies with IR to treat breast cancer have been increasingly used in recent years. Several authors have analysed the oncological safety of these techniques.5–12 Valero et al.6 studied 449 women with SNSMs and after a mean follow-up of 39 months had three LLRs (.7%), none of them in the NAC. Margenthaler et al.7 retrospectively analysed 588 SNSMs and found 1.9% LRRs, none of which were in the NAC. Wu et al.11 analysed 199 SNSMs for ductal carcinoma in situ and during follow-up identified 5% LRR, one of them in the NAC. In the meta-analyses by De la Cruz et al.10 and Lanitis et al.9 there was no difference in the incidence of LLR, in either OS or disease-free survival between MRM and SNSM. Finally, the meta-analysis by Blanckaert et al.12 describes an incidence of LRR between 0% and 8.3%, with an incidence of relapse in the NAC between 0% and 4.1%. Although most of the studies included in these meta-analyses are retrospective or with little follow-up, they all describe an incidence of LRR below 10%,12 which is why the clinical guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 13 have accepted SNSM with IR as a valid option in women with breast cancer in experienced units and multidisciplinary teams. In our study we found an LRR incidence of 6.6% and no relapse in the NAC, similar to that reported in the literature. In fact, the incidence of LRR was lower than the incidence of distant metastases (6.6% vs 8.1%), similar to data presented by other authors such as Van Maaren et al.14 The low incidence of relapse in our study precluded the identification of risk factors for LRR. However, we observed that hormone-sensitive tumours are less frequent in women with LRR. Similar data are described by Wu et al.11 their study determined that the absence of progesterone receptors is an independent risk factor for LRR.

Some authors suggest that radiotherapy may be a method of preventing LRR in women with SSM.15,16 In contrast, the NCCN clinical guidelines13 recommend using the same radiotherapy criteria for SSM as for MRM. Park et al.17 analysed the impact of radiotherapy in women with mastectomy and N1 lymph node involvement. The authors state that the risk of LRR has decreased since the introduction of systemic targeted therapies, therefore the absolute benefit of radiotherapy after mastectomy, even in patients with N1 axillary involvement, is low compared to that reported in older studies.17 They conclude that the indication for radiotherapy after SSM/SNSM should be individualised. The majority of patients with LRR in our study were not treated with radiotherapy on their initial diagnosis, however, our data show no significant difference in the incidence of LRR between women with and without chest wall radiotherapy after SSM/SNSM.

Several authors have described LRR in breast cancer as a heterogeneous disease. However, there are few studies on the prognosis of these relapses in breast-sparing mastectomies. Langstein et al.18 found that chest wall relapses have worse survival than subcutaneous tissue relapses. Similarly, Wu et al.19 found that relapses in the NAC have a lower impact on survival than relapses in subcutaneous tissue, and in turn, these have better survival than lymph node relapses. Our study shows that the behaviour of mastectomy flap relapse differs from that of lymph node relapse. Subcutaneous relapses tend to be late and with a different tumour subtype, suggesting that they may be a new primary in residual glandular tissue. In contrast, lymph node relapses occur in women with locally advanced tumours, they are early and are usually the same tumour subtype, suggesting that this process is progression of the disease. Sekine et al.20 propose a similar theory, suggesting that the cause of lymph node relapse is the inability of systemic therapy to eliminate circulating cells, and thus disease progression. Therefore, disease relapse/progression depends on tumour biology, with Her2+ and triple negative tumours having the highest risk of local relapse and metastasis.21–24 These data support the theory that lymph node relapse is a manifestation of systemic progression, and therefore negatively impacts OS.25–27 In our study, LRR decreased OS, although this was not statistically significant (p = .061). Lymph node relapses are likely to modify OS, but the low incidence of lymph node relapses in our study does not support this theory.

The ideal management of LRR in mastectomy with reconstruction is controversial. The NCCN guidelines13 and Buchholz et al.28 propose that treatment should be multidisciplinary, advocating local resection with free margins with the least permissible morbidity, radiotherapy of the chest wall and/or lymph node chains, if not given previously, and targeted systemic therapy as required according to the tumour subtype. However, there is little literature on the possibility of reconstruction preservation. Mirzabeigi et al.29 reviewed 41 women with LRR after mastectomy and reconstruction, of whom 49% lost reconstruction. Newman et al.30 analysed 372 patients with SSM, showing a 6.2% local relapse rate, with 13% of these women losing their reconstruction. Similar data were published by Wu et al.19 who analysed 128 relapses after mastectomy with reconstruction, with 16% of cases losing their reconstruction. This study found that age older than 50 years, relapse size greater than 2 cm, and multifocality were independent risk factors for loss of reconstruction. They also found that survival was similar in patients with local resection of the relapse versus those with wide resection and loss of reconstruction. In our study, most (88.2%) of the women with a relapse underwent surgery and the reconstruction was preserved in all of them. These good results are probably due to the early detection of relapse (tumours smaller than 2 cm) and the uniformity of the procedure. During follow-up, another local relapse was only detected 10 years after the first relapse. Therefore, as Wu et al.19 argue, local resection while preserving reconstruction appears oncologically safe in selected cases. However, more prospective studies are needed to confirm this theory.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, the low incidence of LRR prevented the detection of risk factors for these relapses and their real impact on OS. Secondly, the absence of a control group with MRM without reconstruction prevents comparison of the safety of the surgical technique. Finally, the heterogeneity of the sample, determined by the evolutionary changes in the surgical treatment in each period and the participation of more than one surgeon, may hinder the interpretation of some results.

In conclusion, LRR is a rare event in women with SSM/SNSM and IR. Mastectomy flap relapse is a different event from lymph node relapse in terms of its time of onset and histological concordance with the primary tumour. Most patients with LRR can preserve their initial reconstruction by local tumour resection and adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant therapies. Our study shows that the diagnosis of LRR after mastectomy and IR does not significantly worsen long-term survival.

FundingNo funding was received for this paper.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.