There is no need for a competition between qualitative or quantitative studies. Each should be framed within the knowledge of the surgical research that is being conducted. However, the quality of both study types must always be ensured by following international guidelines for the publication of research studies. The IDEAL project represents the combination of qualitative and quantitative studies to achieve the same goal: the safety and efficacy of surgical innovation.

Research without the goal of thorough search for knowledge makes no sense. The problem arises when we accept erroneous fundamentals as certainties, or vice versa. Until practically the last third of the last century, surgical research had been based on observation by the so-called ‘great surgeons’, who indicated the most appropriate surgical treatments for each ailment with no other basis other than empirical ones. They applied deductive reasoning, justifying their observations with their preconceived ideas. They also used qualitative research, which avoids quantification. Qualitative researchers make narrative records of the phenomena that are studied through techniques such as observation and unstructured interviews1.

At the end of the last century, quantitative research was introduced more widely among surgeons, defined as research in which the variables are collected and data analyzed quantitatively. The inductive method is applied. However, prior to any quantitative analysis, it is necessary to design the research with a strategy, experimental or non-experimental (those in which the researcher assigns, or does not assign, the study factor to comparable groups), so that later causal relationships can be observed between the variables2.

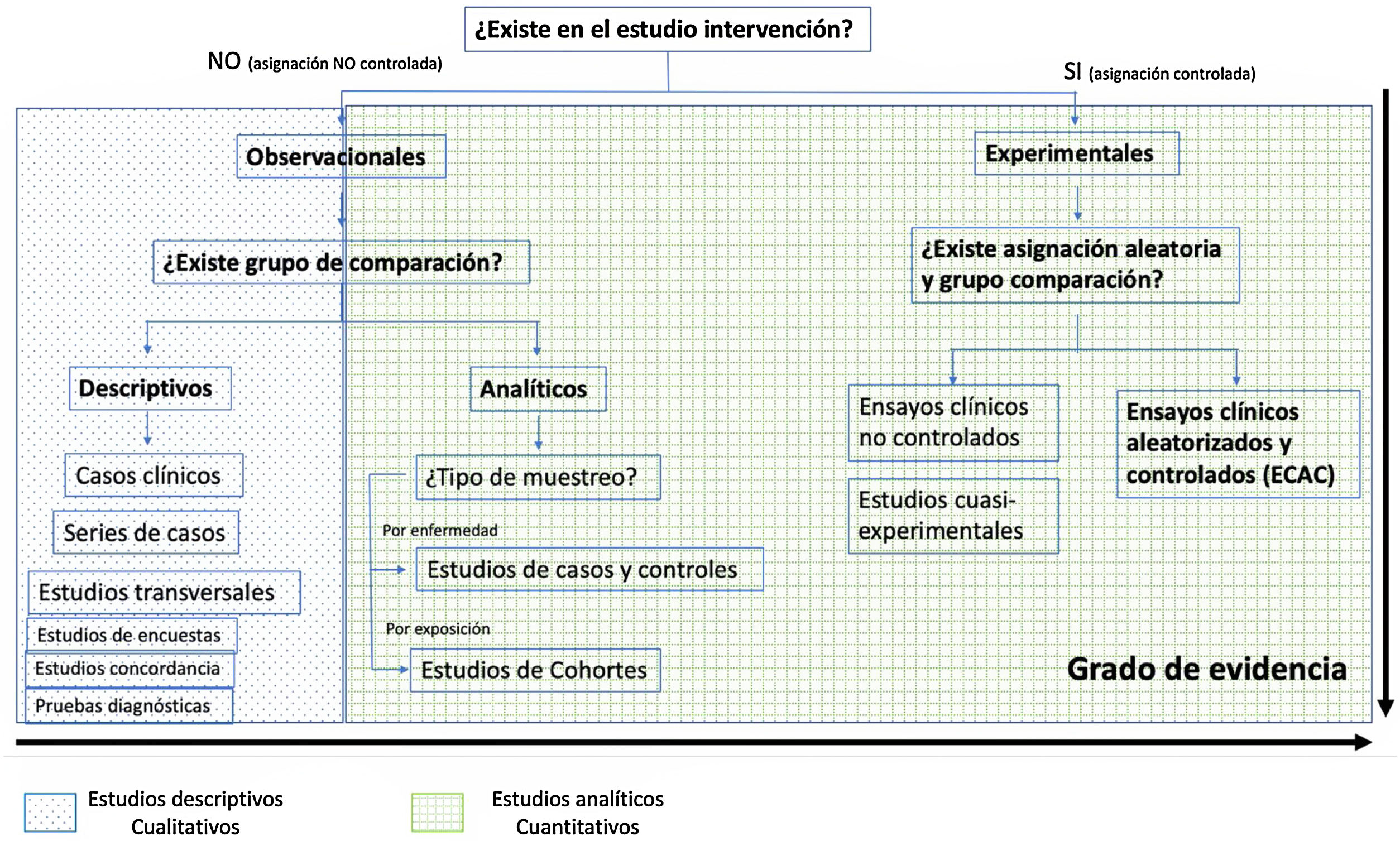

The fundamental difference between both methodologies is that the quantitative one studies the association or relationship between quantified variables, and the qualitative one does so in structural and situational contexts1. Fig. 1 shows the difference between qualitative and quantitative studies with their different level of evidence in the causal sense.

The scientific method (inductive) tries to follow the 3 blocks that are progressively developed: theoretical, methodological and analytical. In the theoretical, an area of study within surgery is delimited and a series of explanatory theoretical hypotheses are proposed, which are subsequently broken down into empirical hypotheses. The methodological one includes the selection of the variables allows for empirical hypotheses to be tested and, secondly, the data collection strategy, which the research plan is based on depending on whether it is experimental or not, as defined previously. Finally, in the analytical block, the formulated hypotheses are compared with the empirical data of the study, applying statistical tests. Therefore, it is necessary to design the research with a strategy that is later able to reveal causal relationships between the variables. Consequently, it is not the statistical method, but rather the research strategy used, that will allow for conclusions to be drawn about causation2.

Quantitative research is not always the best. In recent years, the quality of quantitative studies has been debated. It seems that, with the desire to develop an academic career, there is growing motivation to publish one article after another, and not necessarily with the objective of advancing scientific knowledge3. For this reason, in order to maximize the value of research, guidelines for the publication of clinical research studies were developed at the end of the last century. Their aim was to promote good research practice among clinical scientists, which are now organized within the EQUATOR network (www.equator-network.org). The first evidence-based recommendation on how to publish the results of randomized controlled trials (RCT) was the CONSORT guideline, published in its first version in 1996. Similarly, guidelines have been developed for all the different types of studies, including observational ones (STROBE), as described in other methodology letters4.

As we mentioned at the beginning, we must understand research as a broader project made up of different qualitative and quantitative studies in order to advance scientific knowledge. Thus, when we talk about surgical innovation, we should ask ourselves: Is this new surgical procedure really safe? Has its effectiveness been proven? Is it better than the standard treatment? Rarely have technological advances been presented with scientific evidence.

To answer these questions, the IDEAL project was devised as a set of qualitative and quantitative studies with the common objective of providing this type of answer. In 2007, a new paradigm and a series of recommendations were published that tried to regulate or discuss the safest way to apply surgical innovations (new procedures, invasive medical devices, or complex therapeutic interventions), from the initial experience to the randomized study, with sufficient evidence to determine the clinical importance of any new surgical proposal5–7. This paradigm is called IDEAL, which is the acronym for Idea, Development, Exploration, Assessment and Long-term study, terms that describe the natural history of a surgical innovation. This project is developed in 4 stages, and the 2nd is subdivided into development and exploration8.

In the latest update of this IDEAL project, a ‘pre-IDEAL’ stage was included, which is considered essential before its implementation in humans. This phase entails simulator or experimental animal research, and logically involves an appropriate design methodology and data collection.

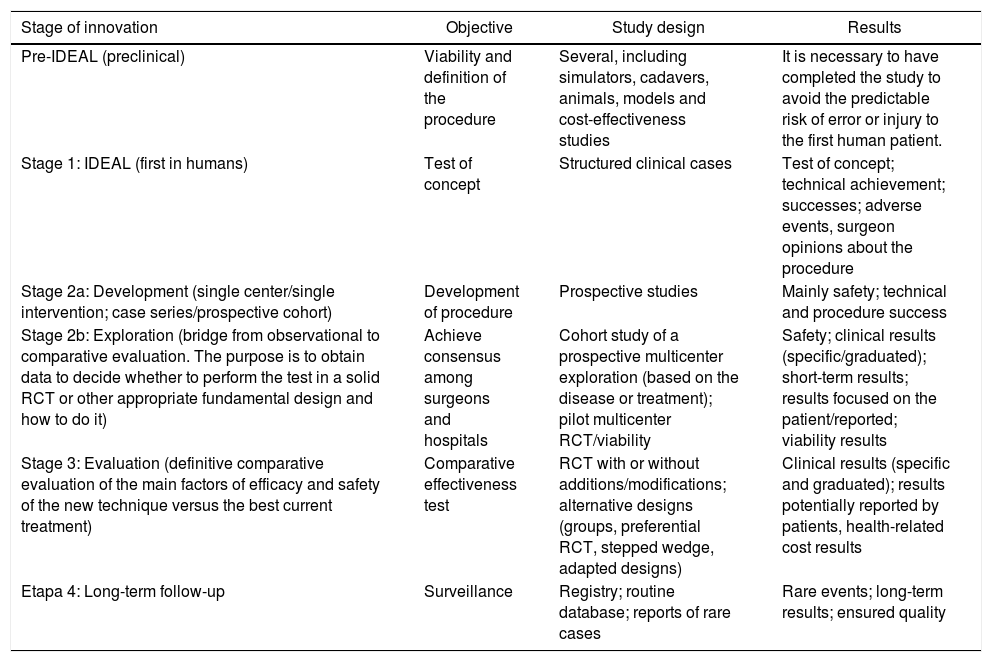

Table 1 describes the different stages of the IDEAL project with its objectives, study designs used, and results expected9.

Stages of the IDEAL project9.

| Stage of innovation | Objective | Study design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-IDEAL (preclinical) | Viability and definition of the procedure | Several, including simulators, cadavers, animals, models and cost-effectiveness studies | It is necessary to have completed the study to avoid the predictable risk of error or injury to the first human patient. |

| Stage 1: IDEAL (first in humans) | Test of concept | Structured clinical cases | Test of concept; technical achievement; successes; adverse events, surgeon opinions about the procedure |

| Stage 2a: Development (single center/single intervention; case series/prospective cohort) | Development of procedure | Prospective studies | Mainly safety; technical and procedure success |

| Stage 2b: Exploration (bridge from observational to comparative evaluation. The purpose is to obtain data to decide whether to perform the test in a solid RCT or other appropriate fundamental design and how to do it) | Achieve consensus among surgeons and hospitals | Cohort study of a prospective multicenter exploration (based on the disease or treatment); pilot multicenter RCT/viability | Safety; clinical results (specific/graduated); short-term results; results focused on the patient/reported; viability results |

| Stage 3: Evaluation (definitive comparative evaluation of the main factors of efficacy and safety of the new technique versus the best current treatment) | Comparative effectiveness test | RCT with or without additions/modifications; alternative designs (groups, preferential RCT, stepped wedge, adapted designs) | Clinical results (specific and graduated); results potentially reported by patients, health-related cost results |

| Etapa 4: Long-term follow-up | Surveillance | Registry; routine database; reports of rare cases | Rare events; long-term results; ensured quality |

RCT: prospective randomized controlled trials.

Medications require the approval of the different phases of clinical trials for their validity and safety. In the same way, before any surgical innovation, the different stages of the IDEAL project must be applied.