Minimally invasive parathyroidectomy, of choice in most cases of primary hyperparathyroidism, shows a high detection rate, based on precise preoperative localization by MIBI scintigraphy (SPECT/CT) and neck ultrasound. Radioguided minimally invasive parathyroidectomy is an even more effective technique, which shortens surgical times, maintains minimal incision and few complications, allows immediate verification of parathyroid adenoma removal and is especially interesting in patients with ectopic lesions or cervical surgical history. In this paper, the indications, protocols and differences between the two available radioguided parathyroid surgery procedures (MIBI and R.O.L.L.) are exposed.

La paratiroidectomía mínimamente invasiva, de elección en la mayoría de casos de hiperparatiroidismo primario, muestra elevada tasa de detección, fundamentada en una precisa localización pre-operatoria mediante gammagrafía con MIBI (SPECT/TC) y ecografía cervical. La paratiroidectomía mínimamente invasiva radioguiada es una técnica aún más efectiva, que acorta los tiempos quirúrgicos, manteniendo mínima incisión y escasas complicaciones, permite además la comprobación inmediata de la exéresis de la lesión paratiroidea y es especialmente interesante en pacientes con adenomas ectópicos o antecedentes quirúrgicos cervicales. En el presente trabajo se exponen las indicaciones, protocolos y diferencias entre los dos procedimientos disponibles de cirugía radioguiada mínimamente invasiva de paratiroides (MIBI y R.O.L.L.).

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is a common endocrine disorder whose prevalence is on the rise1 due to the increase in routine calcium level determination. The incidence is 0.4–82 cases per 100 000 inhabitants2.

In 80%–85% of PHPT cases, the cause is a solitary adenoma, and in the remainder the cause is a multiple adenoma, hyperplasia or parathyroid carcinoma3. In patients who meet surgical criteria1, excision of the gland(s) causing PHPT is the standard treatment, and the only definitive one.

Minimally invasive parathyroidectomy (MIP) is the surgical technique of choice in patients with a single adenoma (the majority), while the indication for bilateral surgery is limited to cases of multiglandular involvement, concomitant surgical indication of thyroid and parathyroid pathology, or parathyroid carcinoma4.

The technological advances made in preoperative localization techniques, especially the incorporation of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT/CT)5 with 99mTc-methoxy-isobutyl-isonitrile (MIBI), make it possible to precisely locate parathyroid lesions and differentiate between single adenoma and multiple disease, consequently establishing the indication for MIP. By associating preoperative ultrasound and scintigraphy with MIBI SPECT/CT, the sensitivity of preoperative detection of adenomas reaches 85%–95%5–7. As a direct result, high success rates are described with MIP for intraoperative localization of the adenoma and cure of PHPT (95%–96.9%)8, which are directly dependent on the exhaustive preoperative evaluation of the images. Therefore, the small percentage of patients in whom the procedure fails (due to involvement of more than one gland or more frequently due to ectopic location of the lesion) could benefit from preoperative radiolabeling of the parathyroid lesion9. Thus, in order to further increase the success of selective parathyroid surgery, use of the radioguided minimally invasive procedure has become widespread.

In 1997, Norman and Chheda10 described the first minimally invasive radioguided parathyroidectomy (MIRP) procedure with preoperative administration of 99mTc-MIBI, which was originally done to avoid intervention failure in cases where there was more than one pathological gland. In addition to incorporating the advantages of MIP versus cervicotomy, MIRP shortens surgical time (mean duration 32−37 min)11–13, while maintaining few complications11,12,13, a minimal incision, and short hospital stay11. The use of locoregional anesthesia has even been proposed11,14, which reduces costs15.

By applying the radioguided procedure, immediate confirmation of the success of the resection is available during the intervention, which reduces the risk of persistent/recurrent PHPT16. Thus, some authors have proposed eliminating intraoperative biopsy or PTH determination17,18, which would also reduce surgical time and costs.

MIRP is effective, safe and offers advantages over conventional MIP19. In more compromised clinical scenarios such as patients with a history of cervical surgery11,20–22 or with ectopic lesions11,13,23–26, it provides a selective surgical approach while also reducing the risk of persistent or recurrent PHPT by ensuring complete excision of the lesion causing PHPT16. In this context, detection rates of 68%–96%11–13,20 have been described in re-operated patients, without increasing the complications inherent to cervical re-operation20. As for the selective approach of ectopic glands13,23,24,26,27, their removal has been achieved in up to 90% of cases, even 60% with minimally invasive access25.

There are two well-differentiated models for preoperative marking of the pathological parathyroid gland for radioguided excision. Apart from the one referred to above with intravenous administration of a radiotracer (99mTc-MIBI), ultrasound-guided intralesional injection of a non-diffusible radiotracer can also be used (99mTc-macroaggregated albumin, or MAA). The latter is a common procedure in Nuclear Medicine for radioisotopic localization of non-palpable lesions (radioguided occult lesion localization, ROLL).

Below, we discuss the different techniques available for the radioguided procedure.

Preoperative localization techniquesAs close as possible to the day of the intervention, a thorough preoperative (diagnostic) imaging evaluation of the patient is essential to determine the number and location of the parathyroid lesions and, consequently, the possibility of performing a minimally invasive approach. Furthermore, this is an unavoidable requirement to establish the indication for the radioguided procedure and, where appropriate, the most appropriate tracer.

Preoperative assessment must be done according to the conventional protocol, initially including two-stage parathyroid scintigraphy with MIBI and cervical ultrasound5,7.

Regarding scintigraphy, we feel it is always necessary to acquire SPECT/CT, which provides precise information on the anatomical location of the parathyroid lesion28. This is of special interest in ectopic lesions, in addition to demonstrating the intensity of uptake and the degree of retention of 99mTc-MIBI. Consequently, the scintigraphic study determines the appropriate time interval between the administration of MIBI and surgery, avoiding the loss of rapid ‘washout’ adenomas, so that the uptake of MIBI by the parathyroid lesion is at its maximum compared to the background at the time of surgery29,30.

Ultrasound is used to determine the size of the lesion and accessibility for intralesional ultrasound injection of the radiotracer (99mTc-MAA), which depends on its size and relationship with neighboring structures (vascular, thyroid).

When nodular thyroid pathology coexists, making it difficult to assess the scintigraphy due to MIBI fixation in said nodules, conventional thyroid scintigraphy with 99mTc may be useful. Also, in cases where ultrasound and MIBI are discordant, a complementary PET study is indicated, preferably choline-PET31.

Indications for Radioguided SurgeryMIRP-MIBIThis isonitrile is administered systemically and is taken up by the parathyroid lesion depending on blood flow and mitochondrial activity. Thanks to the different kinetics of MIBI between parathyroid and thyroid tissue, increased activity persists in the parathyroid adenoma in late images, while it decreases in the thyroid, thereby allowing the parathyroid lesion to be detected. However, some parathyroid adenomas may have a more rapid decrease in activity (‘rapid washout’), while other inflammatory thyroid pathologies (thyroiditis) and/or thyroid nodules may retain the radiotracer longer than normal thyroid tissue.

Radioguided parathyroidectomy with MIBI is indicated when a solitary adenoma is identified in the preoperative diagnostic image that presents sufficient uptake of this radiotracer, preferably in the absence of underlying thyroid pathology11. These conditions are met in up to 70% of PHPT11.

The indication in multiglandular disease (hyperplasia)32 or when thyroid pathology coexists27,33 is more controversial due to the lower efficiency in locating multiple lesions13 and the risk of false positives due to MIBI-positive thyroid nodules16,27. Even with coexisting thyroid nodularity, the benefit of radioguided surgery with MIBI is unquestionable in ectopic adenomas11,23 (Table 1).

Advantages and disadvantages of MIBI/MAA.

| MIBI | MAA | |

|---|---|---|

| Administration | iv | Intralesional (ultrasound) |

| Indication for ectopic adenomas | +++ | + |

| Indication if thyroid nodules | + | +++ |

| Radio-protection | + | +++ |

| Flexible surgical planning | + | +++ |

| Lesion/background uptake | Unfavorable | Optimal |

MAA, albumin macroaggregates; MIBI, methoxy-isobutyl-isonitrile.

99mTc-MAA is a radiotracer that is administered in the pathological parathyroid gland under ultrasound guidance. Given its relatively large size (more than 95% of particles between 10 and 100 micrometers), it remains fixed within the lesion22.

To perform this procedure, the parathyroid adenoma must be solitary, visible and accessible on ultrasound. Therefore, its usefulness is limited in ectopic cases, which are not usually identified by ultrasound (Table 1).

However, it initially has certain advantages over MIBI. It does not depend on the avidity of the adenoma for MIBI: it can also be performed in adenomas that do not take up MIBI, which can happen in up to 40% of cases34. In addition, false positives due to thyroid nodules are avoided.

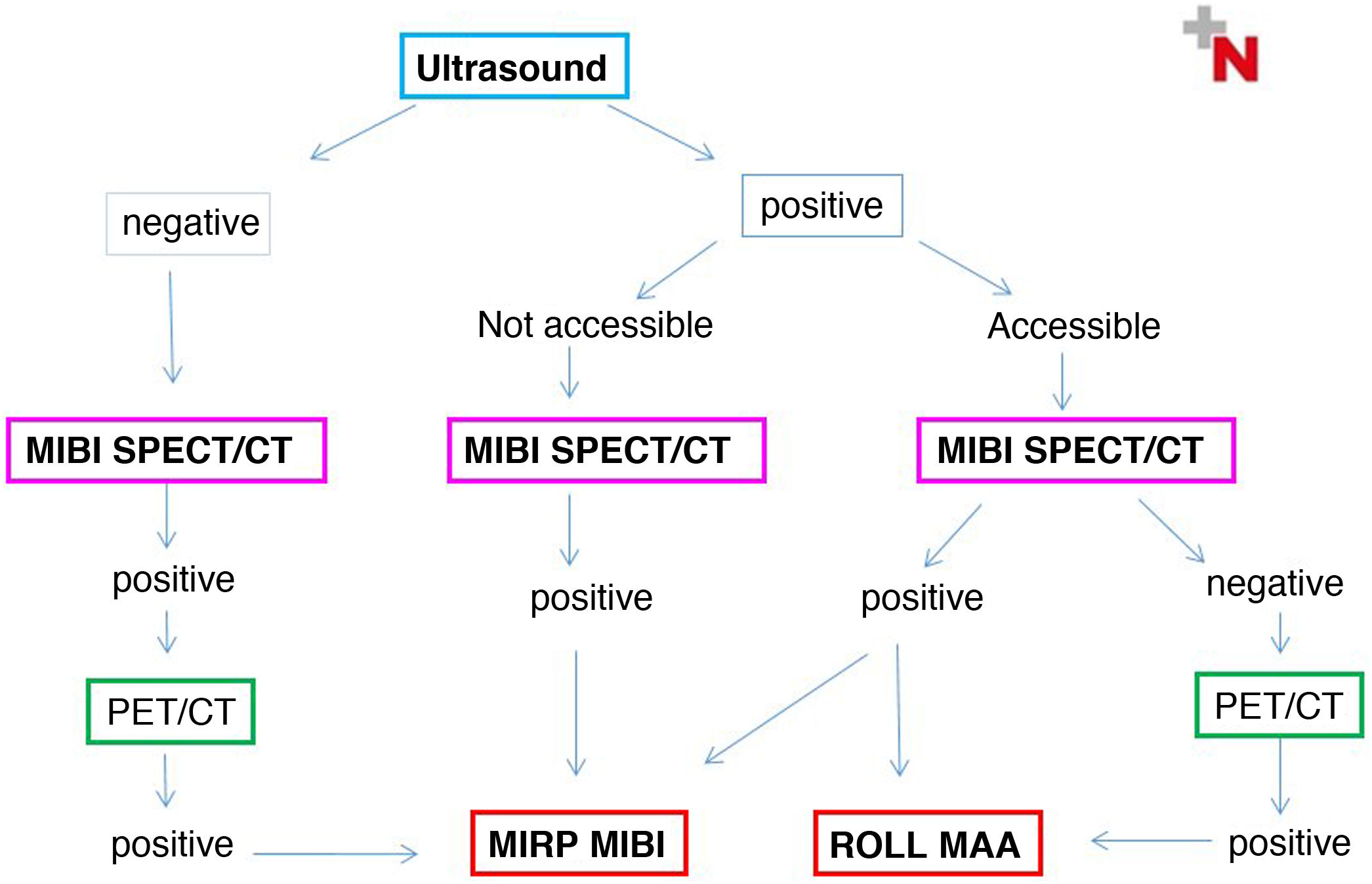

Choice of radioguided procedureTwo positive and strictly coincident preoperative localization techniques are usually required to indicate MIP. In turn, the indication for MIRP and the choice of the most appropriate procedure will first be determined in a multidisciplinary assessment based on the ultrasound accessibility of the lesion and its ability to fix MIBI, and secondly, if any of these is negative, according to the PET image. The diagram that appears in Fig. 1 describes the different possible scenarios.

Thus, MIRP-MIBI can be performed in lesions not visible on ultrasound that are MIBI and PET/CT positive and congruent, and also in MIBI positive lesions that are visible on ultrasound but inaccessible. Ectopic lesions generally correspond to one of the two previous groups.

MIRP-MAA is indicated in MIBI-negative cases that are ultrasound accessible and concordant with PET.

Lastly, in MIBI-enhanced adenomas that are suitable for MAA injection on ultrasound, either procedure can be performed.

Scintigraphic procedureMIRP-MIBIThe uptake of MIBI by the parathyroid glands is a dynamic process, which is a very important factor to take into account: it requires strict coordination between the Nuclear Medicine Department and the surgical team.

The procedure initially proposed by Murphy and Norman10,17, identical to that of classic diagnostic scintigraphy, involves intravenous administration of 740 MBq (20 mCi) of 99mTc-MIBI, with early and late acquisition of conventional images and subsequent radioguided surgery 2.5–3.5 h later. By that time, the thyroid uptake will have washed out and only MIBI parathyroid fixation persists, supposing the rate of parathyroid-thyroid uptake is adequate. This can only be performed in adenomas that retain the radiotracer, not in those that rapidly wash out16. It has been proposed that the preoperative diagnostic study in these ‘long’ protocols should be dispensed with, but this would make it impossible to plan the surgery in advance, which can be risky in endemic areas of goiter and a high risk of concomitant indication for thyroid surgery (Table 2).

MIBI protocols.

| High-dose | Low-dose | |

|---|---|---|

| Radioactive dose (mCi) | 20 | 1−3 |

| Time from injection until surgery | 2–3 h | 10–30 min |

| Scintigraphy on the same day of the surgery | Yes | No |

| Previous diagnostic scintigraphy | Optionala | Yes |

| Indication ‘rapid washout’ adenomas | No | Yes |

| Lesion/background uptake rate | Adequate | Unfavorable |

These ‘long’ protocols, with a high success rate (93.7%–99.1%)10,14,16, use the ‘20% rule’17 as an intraoperative criterion (any tissue with an ex vivo count rate more than 20% of background radioactivity is considered parathyroid adenoma).

Subsequently, Casara et al.23 described a ‘low dose’ protocol: 37–111 MBq (1−3 mCi) of 99mTc-MIBI administered 10−30 min before surgery. These ‘short’ protocols have also shown optimal parathyroid detection rates (93 %–100 %)11,23,24,26,35, they obviously entail less radiation for the patient and the surgical team and avoid false negatives in ‘rapid washout’ adenomas12. However, due to the short time available between MIBI injection and surgery, it is not feasible to acquire a scintigraphic image on the day of the procedure. Therefore, the prior (diagnostic) scintigraphy must be recent12, assuming the absence of significant changes between the two. In addition, at the time of surgery, the thyroid fixation of MIBI will still be high, which can make it difficult to detect the parathyroid adenoma with a probe and discriminate it versus the thyroid (Table 2). Therefore, in these short protocols it is used as an intraoperative criterion for adenoma with an in vivo count 2.5 times higher than the background and 1.5 times higher than the thyroid.

Intermediate procedures between the above have been proposed in order to take advantage of both, with doses of 111−370 MBq (3−10 mCi)20,24,29,32 60–120 min18,29,32 before surgery. These protocols provide a sufficient time margin for the disappearance or washout of thyroid uptake (and consequently good parathyroid-background contrast), without losing ‘rapid washout’ adenomas, while scintigraphy and even SPECT/CT can be performed, if necessary (Fig. 2). In all cases, the skin can be marked with the location of the adenoma using indelible ink.

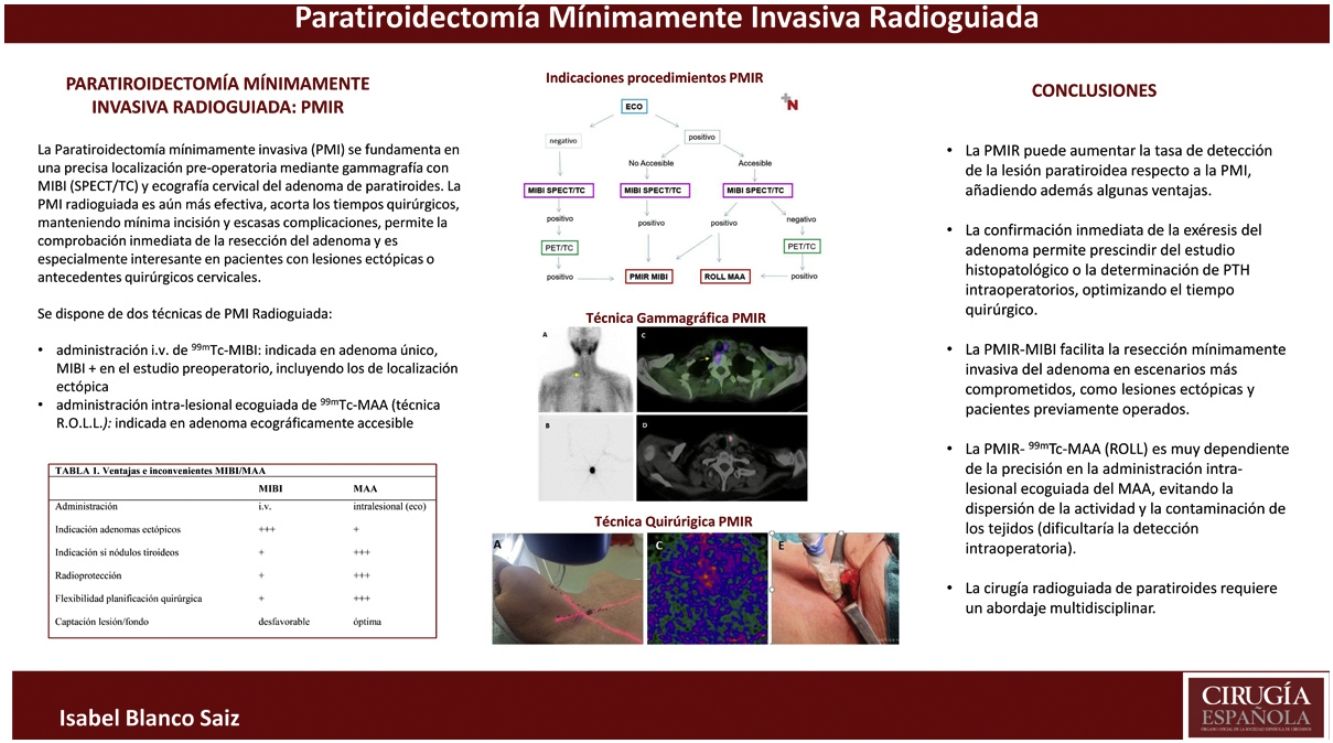

Preoperative image.

Localization with MIBI: planar image (A) showing a small lower right adenoma (arrow), which the SPECT/CT fusion image (C) confirms and locates in an ectopic situation (right pre-vertebral).

Preoperative localization of left lower parathyroid adenoma with the ROLL technique: planar (B) and transaxial SPECT/CT images (D) after the intralesional administration of MAA.

In any event, there do not seem to be significant differences in the success of MIRP depending on the MIBI protocol used36.

MIRP-MAA (ROLL)The administration of 99mTc-MAA is ultrasound-guided and intralesional (Table 1). The size of the radiotracer means that the inoculated activity remains fixed within the lesion, which makes surgical planning more flexible. Thus, it is only necessary to adjust the activity administered to the decay of 99mTc itself and the expected time until the surgery, which can be performed on the same day or the following day: 0.5−2 mCi (185−74 MBq), in a small volume adjusted to the size of the lesion (0.1−0.2 mL).

Therefore, the limitation of this procedure is not the time from the administration of the radiotracer, but rather that the radiotracer is administered precisely inside the lesion, avoiding dispersion and the consequent contamination of the adjacent tissues or leaks along the pathway of the injection needle.

SPECT/CT scintigraphy is also performed to confirm the correct inoculation of the adenoma, meaning the intralesional (concentric) location of the activity and the absence of dispersion or contamination, as well as to mark the skin accordingly (Fig. 2).

Thus, the intraoperative procedure is technically simpler, since the count rate or lesion/background activity is more favorable compared to MIBI, given that the latter is also physiologically captured by other tissues (salivary glands, muscles, nodes).

In this context, MIRP-MAA is radiologically more favorable (less activity administered in a one-day protocol, less uptake in other tissues).

In any event, radioguided parathyroid surgery is a safe procedure in terms of radiological protection, with exposure rates for the surgeon of 1.2 μsv/h in low-dose protocols, which is significantly lower than the permitted dose limit12.

Radioguided surgical procedureFor intraoperative localization of the marked adenoma, the use of two portable detection devices is recommended: a gamma probe (with a detector head measuring 9 mm in diameter, preferably) and, if possible, an intraoperative gamma camera. The gamma probe is essential to direct the radioguided dissection. Portable cameras provide images in real time, which, in addition to increasing the efficacy of radioguided surgical detection of parathyroid adenomas37, facilitates the immediate confirmation of their complete removal and verifies the absence of residual activity in the surgical bed. This results in a lower rate of persistent/recurrent PHPT due to intervention failure compared to non-radioguided surgery16.

Thus, intraoperative imaging increases the safety of the resection, especially in MIRP-MIBI given the physiological fixation of this radiotracer in proximal tissues (muscles, salivary glands, myocardium), which renders the parathyroid/background count rate less than optimal.

As we have previously pointed out, in the ROLL technique, surgical localization can be performed on the day of injection or the following day, adjusting the dose. Meanwhile, in MIRP-MIBI, surgery must be performed on the same day either immediately after injection or within 3 h, depending on the protocol selected.

The surgical procedure includes, in all cases (Fig. 3):

- •

Before the incision: external count (gamma probe) and intraoperative camera image (acquisition centered on the thyroid bed or area of interest, about 10 cm away, for 1−2 min), to determine the exact point of maximum activity, in which the incision will be made.

- •

Incision: approximately 1–1.5 cm

- •

Probe-guided plane dissection until the abnormal gland is identified

- •

Register in vivo activity counts (counts per second [CPS]) of the parathyroid adenoma and the thyroid bed (contralateral isthmus/lobe) and background.

- •

Ex vivo parathyroid lesion count and image

- •

Verify the absence of significant residual activity in the surgical bed; count using the probe and image of the bed with the camera.

Radioguided surgical technique.

Cutaneous localization of the most direct access using a portable gamma camera (A) and gamma detector probe (B). In vivo image with portable camera of the lesion marked with MIBI (C) and MAA (D). Radioguided dissection (E) and excision of the parathyroid adenoma, confirmed ex vivo with the probe (F). Adenoma ex vivo images of MIBI (G) and MAA (H).

When there is agreement between the count with the probe and the intraoperative image of a gland with a pathological appearance in the visual analysis, the surgical procedure is considered finished. It has therefore been proposed that MIRP makes it possible to avoid waiting for confirmation of the excision by intraoperative biopsy or PTH determination17,18.

Special considerations; limitationsMIRP-MIBI is usually the most indicated technique in ectopic adenomas and reoperated patients, but its use may be limited in adenomas that show low uptake of this radiotracer in the preoperative diagnostic study, which happens in a non-negligible percentage of cases and also in patients in whom thyroid nodule pathology coexists11. However, the usefulness of the MIRP-MIBI procedure has even been described in 23% of lesions considered MIBI negative in the preoperative study38. It also requires a certain initial learning curve due to the high background activity during the intraoperative detection process with a gamma probe, a factor that is very different from other usual scenarios of radioguided surgery (detection of the sentinel node, etc.) and which can be even more pronounced in coexisting thyroid nodule pathology. Therefore, thorough evaluation of the preoperative images by the multidisciplinary team is unavoidable.

Furthermore, MIRP-MIBI requires strict organization, coordination and control of the times between injection and surgery to avoid the disappearance of activity at the time of resection. This factor may be a limitation in some Endocrine Surgery Units.

MIRP-MAA is a common procedure in Nuclear Medicine for locating non-palpable lesions (ROLL technique), and, although there are few publications on parathyroid surgery22,34, the results are very good. The limitation in this case is its application to ectopic lesions, a frequent cause of failure of selective intervention, and which are rarely identified by ultrasound (especially prevertebral or mediastinal).

Although the MIRP-MAA procedure is temporarily more flexible, and intraoperative detection is a priori technically simpler because the activity remains fixed within the lesion, the technique is highly dependent on the precision of the ultrasound-guided administration. Especially in parathyroid lesions with more compromised ultrasound access due to their depth and/or small size, it is not uncommon for the liquid compound to become dispersed along the needle path, consequently contaminating the adjacent tissues and even the skin, which can hinder the probe detection process. There could even be a risk of implantation of parathyroid disease, although this has not been reported to date.

In this context, radioguided surgery has been proposed through the intralesional ultrasound implantation of I-125 seeds39,40, a solid millimetric device, with no risk of dispersion. This technique has become widely used in other fields of radioguided surgery since it can be implanted days or even weeks before surgery. However, in its application for parathyroidectomy, a higher risk of displacement and complications in the cervical territory has been described40.

After the introduction of autofluorescence in endocrine surgery41, the use of the hybrid technique (indocyanine green [ICG] together with Tc-MIBI) has also been proposed, which could be indicated for the localization of adenomas in necks that are difficult to access, obese patients, glands with low uptake, ectopic locations, or in the cervical endoscopic approach via the subpectoral route42.

ConclusionsMIRP can increase the detection rate of parathyroid lesions compared to the already high rate of surgical success achieved with MIP, while also providing additional advantages.

First of all, MIRP provides immediate intraoperative confirmation of the removal of the pathological gland, a factor that we believe makes it possible to dispense with the intraoperative histopathological study or PTH determination, which consequently optimizes surgical time.

Secondly, the radioguided approach with MIBI is especially indicated in ectopic lesions, as it facilitates resection through a minimally invasive approach. Likewise, MIRP is of great help in patients with a history of cervical surgery. In both circumstances, the difficulty of surgical location is greater, and the risk for failure of the procedure and complications is higher.

In MIRP-99mTc-MAA (ROLL), intraoperative detection is, in principle, technically simpler, provided that the intra-lesional administration of the radiotracer, guided by ultrasound, is correct. Otherwise, it can involve the dispersion of the radiotracer and the contamination of the adjacent tissues, consequently hindering the process of surgical localization of the lesion.

The radioguided parathyroid surgery procedure requires the close collaboration of the professionals involved and can be incorporated into any Endocrine Surgery Unit. The correct choice of technique, based on multidisciplinary preoperative assessment of the different imaging techniques, is essential. Each group must establish its own methodology.

Conflict of interestsThe present study has received no specific help from public, commercial or non-profit organizations.

FundingThis research has not received specific aid from agencies of the public sector, commercial sector or Non-profit entities.