Surgical site infection is the most frequent and avoidable complication of surgery, but clinical guidelines for its prevention are insufficiently followed. We present the results of a Delphi consensus carried out by a panel of experts from 17 Scientific Societies with a critical review of the scientific evidence and international guidelines, to select the measures with the highest degree of evidence and facilitate their implementation. Forty measures were reviewed and 53 recommendations were issued. Ten main measures were prioritized for inclusion in prevention bundles: preoperative shower; correct surgical hand hygiene; no hair removal from the surgical field or removal with electric razors; adequate systemic antibiotic prophylaxis; use of minimally invasive approaches; skin decontamination with alcoholic solutions; maintenance of normothermia; plastic wound protectors-retractors; intraoperative glove change; and change of surgical and auxiliary material before wound closure.

La infección de localización quirúrgica es la complicación más frecuente y más evitable de la cirugía, pero las guías clínicas para su prevención tienen un seguimiento insuficiente. Presentamos los resultados de un consenso Delphi realizado por un panel de expertos de 17 Sociedades Científicas con revisión crítica de la evidencia científica y guías internacionales, para seleccionar las medidas con mayor grado de evidencia y facilitar su implementación. Se revisaron 40 medidas y se emitieron 53 recomendaciones. Se priorizan 10 medidas principales para su inclusión en bundles de prevención: ducha preoperatoria; correcta higiene quirúrgica de manos; no eliminación del vello del campo quirúrgico o eliminación con maquinilla eléctrica; profilaxis antibiótica sistémica adecuada; uso de abordajes mínimamente invasivos; descontaminación de la piel con soluciones alcohólicas; mantenimiento de la normotermia; protectores-retractores plásticos de herida; cambio de guantes intraoperatorio; y cambio de material quirúrgico y auxiliar antes del cierre de las heridas.

Surgical site infection (SSI) is the most prevalent healthcare-related infection in Europe (19.6%)1 and Spain (21.6%).2 SSI represents a significant financial burden for healthcare systems due to the increased consumption of antibiotics and longer average hospital stay.3

Some 50% of SSI are considered avoidable, so prevention should be a priority for scientific societies. National and international guidelines are published periodically with prevention recommendations, but this does not ensure their routine use in clinical practice.4 The Spanish Surgical Infection Observatory (Observatorio de Infección en Cirugía, or OIC) has reviewed the scientific evidence to synthesize and assess the prevention measures with the highest degree of evidence in order to facilitate their implementation in the departments of the various surgical specialties of Spanish hospitals.

This manuscript summarizes the recommendations for each of the measures analyzed. The reasoning behind these proposals by each group is reflected in more extensive documents.

MethodsOur aim was to propose a Surgical Infection Reduction Program that would be applicable to various types of surgical specialties. To formulate the recommendations, we decided to use the consensus formula based on the modified Delphi method.5

Several working groups were created: A) Project Management – the OIC Coordination Group; B) Scientific Committee – 10 members of the AEC and SEMPSPH; C) Scientific Societies – 17 societies from surgical, medicine and nursing specialties (Table 1); D) Panel of Writers – 73 experts designated by the Societies; E) Operational Coordination by Antares Consulting.

List in alphabetical order of the scientific societies belonging to the Surgical Infection Observatory that participated in the development of the Surgical Infection Prevention Program (PRIQ-O).

| AEC | Asociación Española de Cirujanos |

| AECP | Asociación Española de Coloproctología |

| AEEQ | Asociación Española de Enfermería Quirúrgica |

| AEU | Asociación Española de Urología |

| SEDAR | Sociedad Española de Anestesiología, Reanimación y Terapéutica del Dolor |

| SEACV | Sociedad Española de Angiología y Cirugía Vascular |

| SECCE | Sociedad Española de Cirugía Cardiovascular y Endovascular |

| SECO | Sociedad Española de Cirugía de la Obesidad y Enfermedades Metabólicas |

| SECOM-CyC | Sociedad Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial y de Cabeza y Cuello |

| SECOT | Sociedad Española de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología |

| SECP | Sociedad Española de Cirugía Pediátrica |

| SECPRE | Sociedad Española de Cirugía Plástica Reparadora y Estética |

| SEIMC | Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica |

| SEIQ | Sociedad Española de Investigaciones Quirúrgicas |

| SEMPSPGS | Sociedad Española de Medicina Preventiva, Salud Pública y Gestión Sanitaria |

| SENEC | Sociedad Española de Neurocirugía |

| SEOQ | Sociedad Española de Oncología Quirúrgica |

Selection of the prevention measures to be reviewed. Based on the results of the previous OIC project to identify problems in the implementation of postoperative infection prevention measures,6–9 the Project Management group created an initial list of 36 measures to review.

Evidence analysis methodology. We decided to start with the recommendations of published clinical guidelines and their meta-analyses, prioritizing the guidelines or web pages of: the World Health Organization (WHO)10–12; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)13; National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)14,15; Canadian Patient Safety Institute16; SHEA/IDSA, 2014 update17; Surgical Site Infection Guidelines of the American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society18; National Health Service Scotland19; Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality20; the Zero Surgical Infection Project21; Surgical Infection Prevention Program of Catalonia (PREVINQ-CAT)22; and the recommendations of the Spanish Association of Surgeons.23

When it was necessary to update the information in the guidelines, we carried out searches in the PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library databases using MeSH terminology. All signing researchers were involved in the bibliographic search, review of the selected documents and inclusion decisions.

Creation of the Panel of Writers. In January 2020, the OIC invited scientific societies related with surgical infection to participate in the project. The societies that accepted (Table 1) appointed a minimum of 2 experts in surgical infection to be part of the group of writers, and 36 working groups were created (one for each preselected measure). Each group consisted of 2 coordinators (AEC and SEMPSPH) and 6–9 editors, who were selected based on the relationship of their specialty with the prevention measure.

Delphi technique. The modified Delphi technique with online methodology5 was used. Four Delphi rounds were carried out, while respecting the fundamental principles of this methodology: anonymity, controlled feedback and statistical response to key questions.

Each working group was asked to make a recommendation (high quality of evidence) or a suggestion (moderate/low quality evidence) based on the guidelines and additional evidence. The groups were provided with the GRADE methodology24,25 to classify the evidence (high, moderate, low, or very low) and the strength of the recommendations (strong, weak), according to the quality of the evidence, the risk/benefit ratio, the use of resources and the values and preferences of patients and medical professionals. The reports were compiled into a single document, which was sent by email as the Delphi 1 round. In it, the writers contributed their opinions about the conclusions of the groups in which they had not participated.

The second round consisted of 89 online questions, which broke down the modified recommendations from the previous round. There was an option to add comments or amendments in order to incorporate feedback from panel members for later rounds. The form of the second round was completed by 66 writers (90.4%).

Using the responses and comments from round 2, the recommendations were redefined, thereby creating the content for round 3 in a new form with 84 questions. All 73 editors participated in this round (100%). Given the controversy around certain recommendations, a 4th round was carried out, which was limited to these specific factors and had a response rate of 97.3%.

Consensus was defined as agreement ≥80% for each of the recommendations. The members of the Editorial Committee held numerous online meetings to monitor the progression of the rounds, discuss special aspects, and to finally decide on the prioritization of the recommendations.

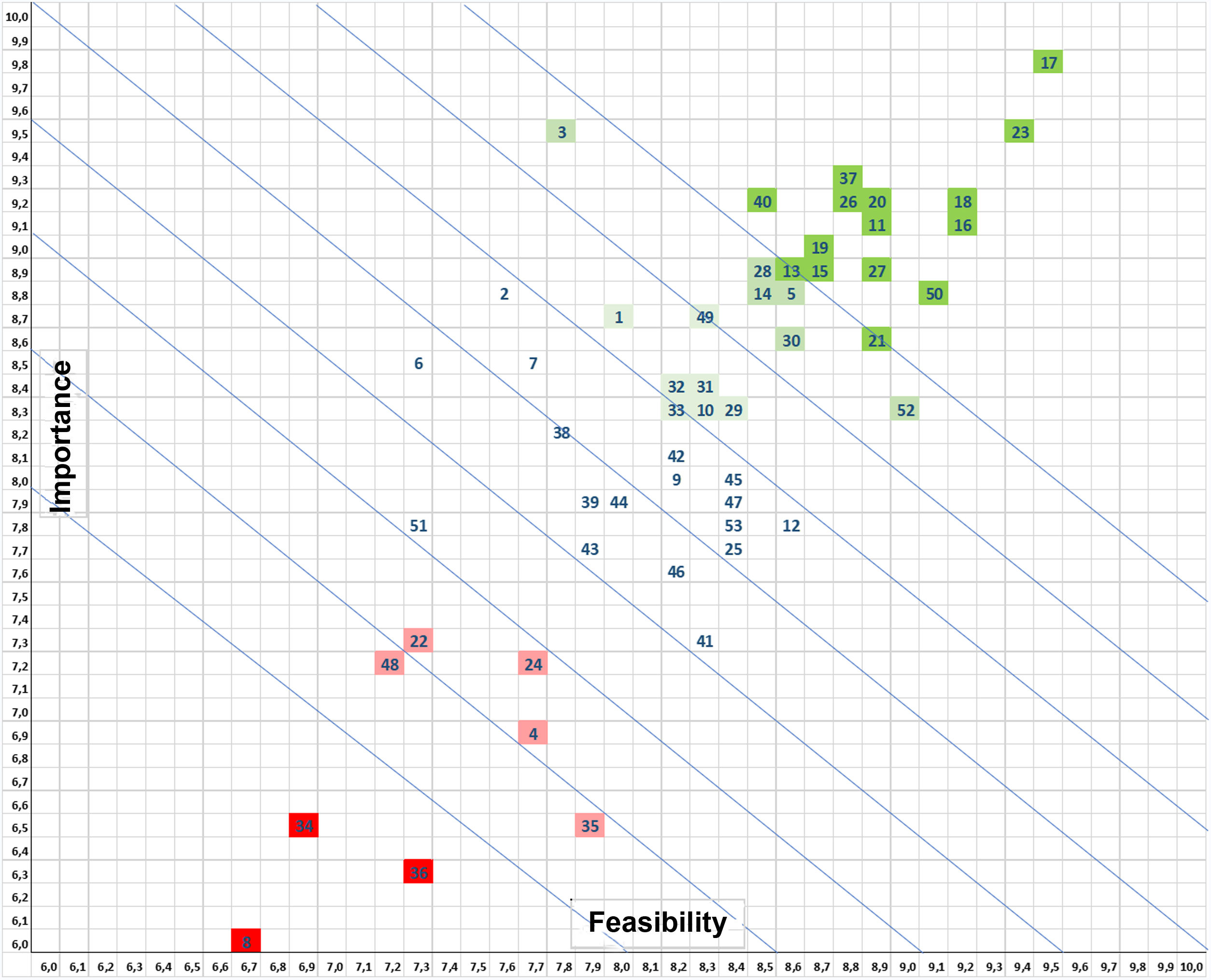

Prioritization of prevention: impact and feasibility. To prioritize the preventive strategies, the Editorial Committee used a simplified scheme of categories for possible proactive interventions, which were ‘graded’ for impact and feasibility.26,27 Each of these dimensions was scored on a scale of 0–10, resulting in a simple 2 × 2 framework.

ResultsThe percentage of agreement of the SSI prevention recommendations is shown in Table 2. Table 3 shows some essential generic recommendations that, in the opinion of the Scientific Committee, should be implemented in all healthcare systems.

Degree of agreement with the recommendations according to the Delphi method.

| Measure | Agreement percentage |

|---|---|

| PREOPERATIVE PERIOD | |

| Patient information and empowerment | 94.52% |

| Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs and infection prevention bundles | 100.00% |

| Epidemiological surveillance of surgical site infection | 100.00% |

| No discontinuation of immunosuppressive agents in surgery with low risk of infection | 94.52% |

| In surgery with a high risk of infection, individualize dose modification according to the immunosuppressor drug and baseline pathology. | 97.26% |

| No prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with immunosuppressive drugs | 98.63% |

| Preoperative nutritional assessment before major surgery | 100.00% |

| Optimized nutritional support for malnourished patients before surgery | 100.00% |

| No perioperative immunonutrition in major surgery | 93.15% |

| No laminar airflow ventilation systems in the context of operating room ventilation | 95.89% |

| Maintain room temperature of operating rooms between 21 °C and 23 °C | 95.89% |

| Preoperative shower | 100.00% |

| Shower with non-pharmacological soap or with antiseptic soap solution | 98.63% |

| Provide the patient with instructions for preoperative showering. | 91.78% |

| Screening and decolonization of patients with Staphylococcus aureus in high-risk clean surgery | 94.52% |

| Oral antibiotic prophylaxis associated with mechanical bowel preparation in elective colorectal surgery | 94.52% |

| Mechanical bowel preparation in colorectal surgery | 97.26% |

| Do not routinely remove hair. | 97.26% |

| If hair removal is necessary, do so outside the operating room. | 100.00% |

| If hair removal is necessary, the patient should not do so at home. | 97.26% |

| If hair removal is necessary, it should be done in the hospital with clipper with a disposable head. | 100.00% |

| Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis according to hospital guidelines | 100.00% |

| Infusion of antibiotic IV prophylaxis within 60 min before incision | 100.00% |

| In orthopedic-trauma procedures, do not apply the hemostatic tourniquet until prophylactic antibiotic infusion is completed. | 98.63% |

| In cesarean sections, administer antibiotic prophylaxis within 60 min before the incision. | 97.26% |

| Infuse antibiotic prophylaxis in the surgical area. | 100.00% |

| Use maximum doses of antibiotics for prophylaxis, adjusting doses according to the characteristics of the patient. | 97.26% |

| Intraoperative redosing of the antibiotic if blood loss is greater than 1500 mL or if surgery is longer than double the half-life of the antibiotic | 98.63% |

| Single preoperative dose of prophylaxis in most procedures | 100.00% |

| In prosthetic orthopedic and cardiac surgery, prolong prophylaxis for a maximum of 24 h. | 89.04% |

| Use endoscopic techniques (thoracoscopy, laparoscopy, arthroscopy) when indicated. | 100.00% |

| Use surgical scrubs exclusively for the surgical area. | 87.67% |

| The surgical team should use a sterile gown (reusable or disposable material). | 98.63% |

| Use a mask that covers the nose and mouth in the surgical area. | 94.52% |

| Use a cap to completely cover the scalp, hair and nape of neck. | 98.63% |

| Use shoes exclusively for the clean area of the surgical area. | 89.04% |

| Do not perform surgical hand preparation with artificial nails or significant abrasions on hands or forearms. | 89.04% |

| Remove watches, rings and bracelets before surgical hand preparation. | 98.63% |

| Do not use jewelry, bracelets, watches or nail polish in the surgical area. | 98.63% |

| Preoperative hand preparation including hands, forearms and elbows, with an alcoholic solution or antimicrobial soap. | 100.00% |

| First handscrubbing of the day with clorhexidine soap | 93.15% |

| For succesive hand preparation: equivalence of handrubbing with an alcoholic solution and hand scrubbing with chlorhexidine soap and water | 95.89% |

| Keep nails short (less than 5 mm) and clean the subungual space under the faucet with a disposable plastic utensil. | 95.89% |

| Do not use surgical scrub brush for surgical hand preparation. | 100.00% |

| Duration of surgical hygiene: 2−3 min | 97.26% |

| INTRAOPERATIVE PERIOD | |

| Limit the noise in the operating room, especially during anesthesia induction. | 98.63% |

| Limit the opening of doors, foot traffic and number of people in the operating room. | 98.63% |

| Mute personal mobile phones and limit phone use to medical care issues. | 90.41% |

| Use double gloves as a universal protection measure for the surgical team. | 79.45% |

| Antisepsis of undamaged skin in adult patients with an alcohol solution (preferably 2% chlorhexidine gluconate with 70% alcohol). | 98.63% |

| Antisepsis of undamaged skin of newborns with a 0.5% aqueous chlorhexidine solution | 100.00% |

| Antisepsis of undamaged skin of children <2 years of age with aqueous solutions of 1%–2% chlorhexidine or 5%–7% povidone iodine. | 100.00% |

| Antisepsis of undamaged patient skin with 0.5%–1% aqueous chlorhexidine solutions or 1% povidone iodine, or 0.04%–0.1% poli-hexamethylene-biguanide. | 100.00% |

| Let antiseptics act 3−5 min and air dry before placing surgical drapes. Do not dry with gauze or towels. | 100.00% |

| Use extreme safety measures to avoid fires and burns with the application of alcohol-based antiseptics. | 100.00% |

| Single-dose applicators can minimize risks and optimize the methodology of antisepsis. | 93.15% |

| Oral mucosa antisepsis: single mouthwash with 0.12%–0.2% aqueous chlorhexidine solution for 1 min | 93.15% |

| Vaginal mucosal antisepsis: 2%–4% aqueous chlorhexidine solution, just before initiating surgery | 93.15% |

| Antisepsis in eye surgery: 5% aqueous ophthalmic povidone iodine in drops on the surface of the eye 5 min before surgery | 94.52% |

| Antisepsis of nasal mucosa: 0.5%–5% aqueous povidone iodine in nasal drops, 5 min before surgery | 91.78% |

| Antisepsis of anal mucosa: 5%–10% aqueous povidone iodine, letting the antiseptic act for 3−5 min just before surgery | 90.41% |

| Do not use antimicrobial sealants after the intraoperative preparation of the surgical field. | 98.63% |

| Do not use plastic adhesive incise drapes to cover the surgical field. | 97.26% |

| If it is necessary to affix the drapes and seal the field, use plastic adhesive incise drapes impregnated with antimicrobials. | 93.15% |

| Do not use high fractions of inspired oxygen (>80%) under general anesthesia. | 93.15% |

| Monitor patient body temperature in procedures that last longer than 30 min. | 100.00% |

| Maintain core temperature ≥36 °C in major surgical procedures >30 min. | 97.26% |

| Exclusive or combined use of hot air blankets, thermal mats, liquid warming systems for infusion or irrigation of cavities to 37 °C and gas warming systems for laparoscopy. | 98.63% |

| Apply temperature maintenance systems throughout the perioperative period (preoperative/intraoperative/postoperative). | 100.00% |

| ‘Non-strict’ control of perioperative blood glucose levels in diabetic and non-diabetic patients in risk surgery (objective: levels below 180 mg/dL) | 97.26% |

| In cardiac surgery, strict control of perioperative glucose levels in diabetic and non-diabetic patients | 97.26% |

| Strict control of blood volume to avoid deficit or excess extracellular volume | 95.89% |

| Use double-ring plastic protector-retractors in clean-contaminated and contaminated surgery and in thoracotomy of cardiac surgery with implants. | 97.26% |

| Sterile surgical gown of reusable or disposable material | 97.26% |

| Moderate lavage of the cavities with saline solution to remove clots and detritus (there is no evidence that irrigation increases or decreases SSI) | 95.89% |

| Irrigation of cavities with aqueous antiseptic solutions is not recommended. | 95.89% |

| Irrigation of surgical cavities with antibiotic solutions is not recommended. | 98.63% |

| Irrigation of the surgical wound with a moderate amount of saline under pressure at the end of the procedure can reduce SSI risk. | 95.89% |

| Surgical wound irrigation with low-concentration aqueous povidone-iodine solution (<1%) can reduce SSI, particularly in clean and clean-contaminated surgery. | 93.15% |

| Surgical wound irrigation with antibiotic solutions is not recommended. | 95.89% |

| Use of antiseptic-impregnated sutures for closure of the surgical wound, especially in clean surgery: when absorbable sutures are indicated. | 91.67% |

| Use a glove change protocol during surgery. | 100.00% |

| Change surgical and auxiliary instruments before wound closure in clean-contaminated, contaminated and dirty surgery. | 91.78% |

| POSTOPERATIVE PERIOD | |

| Prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy over the closed wound in patients at high risk for incisional infection or seroma | 90.41% |

| Use a conventional dressing occluding the surgical wound for 48 h. | 100.00% |

| Shower 48 h after surgery, with soap and water, after which the wound can be left uncovered. | 100.00% |

Generic measures not included in postoperative infection prevention bundles, but considered essential for its evaluation, control and reduction.

| Epidemiological surveillance of surgical site infection |

| Patient information and empowerment |

| Use of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programs |

| Use of infection prevention bundles and checklists |

| Teamwork in the surgical area |

| Preoperative nutritional assessment |

| General patient optimization, including compensation for underlying pathologies, adjusted doses of chronic and immunosuppressive treatments, and nutritional status |

| Appropriate surgical scrubs |

| Optimization of circulation and the operating room environment |

Fig. 1 shows the prioritization matrix from which the 10 measures shown in Table 4 were selected, comprising the PRIQ-O General Bundle. Using the same prioritization criteria, the Committee selected various complementary measures to create the Specific Bundles for specific surgical specialties, such as the colorectal (Table 5), cardiac (Table 6) and orthopedic trauma surgery (Table 7) bundles.

Matrix for prioritizing prevention measures according to the assessment of their importance for preventing surgical site infection and their feasibility or applicability in the healthcare setting. The most highly valued generic measures (dark green) include adequate IV antibiotic prophylaxis, proper surgical hand preparation, maintained normothermia, the use of endoscopic techniques and plastic wound protectors, body hair management, skin antisepsis with alcoholic solutions, preoperative shower, and changes of gloves and surgical instruments at the end of the intervention. The least valued or discouraged measures (red) are preoperative immunonutrition, sealants over the operative field and the use of perioperative high inspired oxygen fractions.

Importance

Feasibility

1 Patient information and empowerment

2 Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs and bundles of infection prevention

3 SSI surveillance

4 Perioperative discontinuation of immunosuppressive agents

5 Antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with immunosuppressive agents

6 Preoperative nutritional assessment

7 Preoperative nutritional support

8 Immunonutrition

9 Operating room ventilation systems

10 Operating room temperature

11 Preoperative shower

12 Screening for/decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus

13 Prophylaxis with oral antibiotics in colorectal surgery

14 Mechanical bowel preparation in colorectal surgery

15 Do not remove hair

16 Clippers for hair removal

17 Adequate systemic antibiotic prophylaxis

18 Modification of the antibiotic prophylaxis and intraoperative redosing

19 Postoperative duration of the antibiotic prophylaxis

20 Use of endoscopic techniques and minimally invasive surgery

21 Surgical scrubs

22 Use of jewelry, artificial nails, nail polish, piercings

23 Surgical hand preparation

24 Environment, foot traffic and noise in the operating room

25 Use of double gloves

26 Antisepsis of intact patient skin

27 Antisepsis of damaged patient skin

28 Application method of skin antisepsis

29 Antisepsis of oral mucosa

30 Antisepsis of vaginal mucosa

31 Antisepsis in ocular surgery

32 Antisepsis of nasal mucosa

33 Antisepsis of anal mucosa

34 Antimicrobial skin sealants on the surgical field

35 Plastic adhesive incise drapes

36 Perioperative hyperoxygenation

37 Maintaining normal body temperature (normothermia)

38 Perioperative blood glucose control

39 Maintenance of adequate circulating volume control/normovolemia

40 Wound protector/retractor

41 Drapes and gowns

42 Irrigation of cavities with saline

43 Irrigation of cavities with antiseptic solutions

44 Irrigation of cavities with antibiotic solutions

45 Incisional wound irrigation with saline

46 Incisional wound irrigation with antiseptic solutions

47 Incisional wound irrigation with antibiotic solutions

48 Antimicrobial-coated sutures

49 Changing of surgical gloves

50 Changing of surgical and auxiliary instruments

51 Prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy

52 Wound dressings

53 Postoperative shower

PRIQ-O general recommendations, prioritized according to their importance in the prevention of surgical site infection and the feasibility of their routine application.

| 1 | Preoperative shower |

| 2 | Adequate intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis |

| 3 | Do not remove hair; if necessary, remove it with a clipper |

| 4 | Skin antisepsis with alcohol-based chlorhexidine |

| 5 | Surgical hand preparation |

| 6 | Use of endoscopic techniques and minimally invasive approaches |

| 7 | Maintain normothermia |

| 8 | Plastic wound protectors-retractors in surgery with high risk of SSI |

| 9 | Intraoperative glove change protocol |

| 10 | Change of surgical and auxiliary instruments before closing wounds in surgery with high risk of SSI |

PRIQ-O: program to reduce surgical site infection of the Spanish Surgical Infection Observatory (Programa de Reducción de la Infección Quirúrgica del Observatorio de Infección en Cirugía).

Specific prioritized recommendations for Colorectal Surgery (in addition to the general recommendations).

| 1 | Implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs |

| 2 | Oral antibiotic prophylaxis |

| 3 | Mechanical bowel preparationa |

| 4 | Glove change after anastomosis and before closure of the laparotomy |

| 5 | Change of surgical and auxiliary material before closing laparotomy |

Specific prioritized recommendations for Cardiothoracic Surgery (in addition to the general recommendations).

| 1 | Screening for/decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus |

| 2 | Prolonged prophylaxis is acceptable for a maximum of 24 h |

| 3 | Strict control of preoperative blood glucose levels in diabetic and non-diabetic patients |

| 4 | Prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy in patients at high risk of incisional infection or formation of seromas |

Specific prioritized recommendations for Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology (in addition to the general recommendations).

| 1 | Screening for/decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus |

| 2 | Prolonged prophylaxis is acceptable for a maximum of 24 h. |

| 3 | Use double gloves. |

| 4 | Change gloves after placing the surgical field and before cementation. |

| 5 | Change gloves before manipulating a prosthesis. |

Patient information and empowerment. Recommendation 1. The patient should be duly informed of the preoperative measures to reduce SSI and be involved in their application (preoperative shower, no removal of hair at home, bowel preparation, abstinence from tobacco, recommendations for nutrition and fasting, maintenance of body temperature, medication intake, etc) and in the detection of postoperative infection (self-monitoring for symptoms and wound care).

ERAS programs and infection prevention bundles. Recommendation 2.Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols should be used, and SSI prevention bundles in the form of check-lists or verification lists are recommended. These measures must be comprehensible, easy to apply, widely disseminated among the personnel in the surgical area, accompanied by a training program, while their proper compliance should be verified.

Surveillance of Surgical Site Infection. Recommendation 3. Epidemiological surveillance programs for SSI should be established in procedures considered a priority, covering the first 30–90 postoperative days (depending on the type of surgery).

Management of perioperative immunosuppressive treatment. Recommendation 4. In patients with immunosuppressive therapy due to previous pathologies (corticosteroids, biological agents, etc.) who are undergoing surgery with a low risk of infection, it is suggested not to withdraw the treatment, but to maintain and/or adjust its dosage during the perioperative period. Before procedures with a high risk of infection or with implants, it is suggested to individualize any dose modification according to the drug and the baseline pathology, in agreement with the patient's referring specialist.

Antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with immunosuppressive treatments. Recommendation 5. It is not recommended to prolong the usual antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with immunosuppressive treatment.

Preoperative nutritional assessment. Recommendation 6. A standardized preoperative nutritional assessment is recommended before major surgery, if possible, within the framework of a prehabilitation protocol.

Preoperative nutrition. Recommendation 7. Nutritional optimization of malnourished patients is recommended before surgery.

Immunonutrition. Recommendation 8. There is not enough evidence to recommend perioperative immunonutrition in patients undergoing major surgery.

Operating room ventilation systems. Recommendation 9. The systematic use of laminar airflow ventilation systems is not necessary in operating rooms. In accordance with technical regulations, 15–29 air exchanges/hour are recommended. In addition, positive air pressure of 20–25 pascals of pressure should be achieved, and HEPA filters should be used.

Room temperature of the operating room. Recommendation 10. It is recommended to maintain the operating room temperature between 21° and 23°, except for surgery in major burns and in neonates, where it may be higher.

Preoperative shower. Recommendation 11. A patient shower is recommended just before surgery, either with a non-pharmacological soap or with an antiseptic soap solution.

The patient should be provided with instructions, explaining how the shower should be done, the number of soap applications, and the action time of the soap solutions (written protocol and infographic).

Screening for/decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus. Recommendation 12. Before high-risk clean surgery (cardiothoracic, orthopedic, and implant neurosurgery), screening for nasal S. aureus is recommended, followed by decolonization.

Oral antibiotic prophylaxis in colorectal surgery. Recommendation 13. Oral antibiotic prophylaxis associated with antegrade mechanical bowel preparation is recommended in elective colorectal surgery. It should be done the day before surgery with active antibiotics against aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms and as separate as possible from the bowel preparation.

Mechanical bowel preparation for colorectal surgery. Recommendation 14. Isolated mechanical bowel preparation (without oral antibiotics) is not recommended in elective colorectal surgery.

Hair management. Recommendation 15.Routine hair removal is not recommended. Hair removal is only recommended when there are difficulties for surgical exposure, following the instructions of the surgical team.

Recommendation 16.If hair removal is required: self-shaving at home is not recommended; removal is recommended outside of the operating room; the use of a blade is not recommended; it is recommended to use an electric clipper with a disposable head, in the hospital by qualified staff, outside the surgical area and as close as possible to the start of the surgical intervention.

Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis. Recommendation 17.IV antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended within the framework of updated hospital protocols. Infusion of antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended within 60 min prior to incision. In trauma and orthopedic procedures that require exsanguination and hemostatic tourniquet, administration of the antibiotic should be finished before applying the tourniquet. Like other procedures, in caesarean sections it is recommended to administer antibiotic prophylaxis within 60 min prior to the incision. The infusion of prophylaxis in the surgical area is recommended, which ensures the best compliance with the infusion protocol, the detection or treatment of possible adverse reactions and the recording of its administration in the patient's medical file.

Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis. Dosage and duration. Recommendation 18.It is recommended to use the maximum doses of antibiotics for prophylaxis. Dose adjustment is recommended based on weight, renal function, degree of obesity, and volume of distribution, in accordance with hospital protocols.

Intraoperative redosing of the prophylactic antibiotic is recommended if there is blood loss greater than 1500 mL or if the duration of the operation doubles the actual half-life of the antibiotic (from the end of the first dose infusion). In the case of cephalosporins with a short half-life or amoxicillin-clavulanate, it is necessary to repeat the dose (approximately every 3−4 h).

Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis. Duration. Recommendation 19.In most procedures, there is no evidence to recommend more than one preoperative antibiotic dose (with intraoperative redosing when appropriate). In general, prolonging prophylaxis beyond wound closure is not recommended.

As an exception, in prosthetic orthopedic surgery and cardiac surgery it is acceptable to extend prophylaxis up to a maximum of 24 h.

Use of endoscopic techniques and minimally invasive approaches. Recommendation 20.The use of endoscopic techniques (thoracoscopy, laparoscopy, arthroscopy), minimally invasive approaches and endovascular techniques are recommended whenever indicated.

Surgical team equipment. Recommendation 21.It is recommended to wear surgical clothing exclusively for the surgical area, which should be replaced when leaving or re-entering the area. The operating team (surgeons and instrumentalists) should wear sterile gowns, which can be made of reusable or disposable material.

The use of a mask is recommended in both restricted and semi-restricted areas of the surgical area. The mask must cover the mouth and nose, must be tied in such a way that there is no opening/ventilation on the sides, must not be worn around the neck, and must be replaced before each operation.

The use of a cap that completely covers the scalp, all the hair, and the nape of the neck is recommended.

The use of exclusive footwear for the clean area of the surgical area is recommended.

Use of jewelry, artificial nails and nail polish. Recommendation 22.The use of jewelry, bracelets, watches and nail polish is not recommended among medical professionals in the surgical area.

It is not recommended for operating room staff with artificial nails or significant wounds or scrapes on the hands or forearms to perform surgical hand hygiene or participate in surgical procedures.

Surgical hand hygiene. Recommendation 23.Preoperative surgical hygiene is recommended, including hands, forearms and elbows, with an antimicrobial soap or alcoholic antiseptic solution, according to the protocol of the surgical area.

It is suggested that the first surgical scrub of the day be carried out with a water-based soap solution of chlorhexidine gluconate (which has more residual activity). As an alternative, a hygienic wash with non-medicated soap and water is suggested, followed by drying and surgical rub with an alcohol-based solution.

For successive surgical hand preparation, either an alcohol-based solution can be chosen (rubbing with the hand, not using a brush or sponge) or a water-based soap solution of chlorhexidine gluconate, depending on personal preference or protocol.

It is recommended to keep the nails trimmed (less than 5 mm) and, if necessary, the subungual space cleaned under the tap with a disposable, single-use plastic utensil. Scrubbing with a brush is not recommended. A duration of surgical hygiene of 2−3 min is recommended.

Mobility and environment in the operating room. Recommendation 24.The operating room door should remain closed as long as possible, while the traffic and the number of people inside the operating room should be limited.

Noise should be limited in the operating room, especially during anesthetic induction. Music can be listened to in a judicious and consensual manner, as long as it does not affect communication among the surgical team. It is recommended to silence personal phones. Mobile phone use should be limited to healthcare issues.

Use of double gloves. Recommendation 25.The use of double gloves is recommended as a universal protection measure for the surgical team, especially during orthopedic and trauma surgery.

Skin antisepsis. General issuesA recent change in legislation (Resolution of June 2, 2021, of the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products, which attributes the status of medicine for human use to antiseptics intended for the preoperative surgical field and for the disinfection of the injection point)28requires that, as of June 2022, antiseptic products intended for the preoperative surgical field and for disinfection of the skin before injections must have the status of ‘medicine for human use’, not biocide. Chlorhexidine solutions and alcohols should not be used in the vicinity of the eye, middle ear, mucous membranes or nerve tissue.

Antisepsis of undamaged patient skin. Recommendation 26.For intact skin of adult patients, it is recommended to decontaminate the skin with an alcoholic solution that is adequate in quantity and extension. 2% chlorhexidine gluconate with 70% alcohol is preferred due to its greater residual effect.

In children <2 years of age, aqueous solutions of 1%–2% chlorhexidine or 5%–7% povidone-iodine are recommended, except in neonates, in whom iodine should not be used and 0.5% aqueous chlorhexidine is preferred.

Antisepsis of damaged patient skin. Recommendation 27.In damaged skin, aqueous solutions are recommended: 0.5%–1% chlorhexidine or 1% povidone-iodine or 0.04%–0.1% polyhexamethylene biguanide.

Method of application of skin antisepsis. Recommendation 28.All antiseptics should be left to act on the skin for a recommended duration of at least 3−5 min and then be allowed to air dry before placing surgical drapes. Drying with gauze or blotting paper is not advisable.

During the application of alcohol-based antiseptics, it is recommended to heighten safety measures to avoid the risk of fires and burns, as well as splashing of the eyes or ears of both the patient and staff. The use of single-dose applicators can minimize the risks of excess product and optimize the skin antisepsis method.

Oral mucosal antisepsis. Recommendation 29.In surgery of the oral mucosa, a single mouthwash with 0.12%–0.2% aqueous chlorhexidine solution for intraoral use for 1 min is suggested just before surgery.

Vaginal mucosal antisepsis. Recommendation 30.In hysterectomies and caesarean sections, antisepsis with 2% or 4% aqueous chlorhexidine is suggested just before starting the surgical intervention.

Antisepsis in eye surgery. Recommendation 31.In eye surgery, antisepsis with 5% aqueous ophthalmic povidone iodine drops on the ocular surface 5 min before surgery is suggested. The use of chlorhexidine is not recommended due to the high risk of keratitis.

Nasal mucosal antisepsis. Recommendation 32.In surgery of the nasal mucosa, antisepsis with 0.5%–5% aqueous povidone-iodine in nasal drops is suggested 5 min before surgery.

Anal mucosal antisepsis. Recommendation 33.In surgery of the anal mucosa, antisepsis with 5%–10% aqueous povidone-iodine is suggested just before the intervention, allowing the antiseptic to act for 3−5 min.

Use of sealants on the skin of the surgical field. Recommendation 34.The use of antimicrobial sealants after intraoperative skin preparation is not recommended.

Plastic adhesive incise drapes to cover the surgical field during surgery. Recommendation 35.It is not recommended to use transparent plastic adhesives incise drapes to cover the surgical field.

In interventions that require fixation of surgical drapes and stable sealing of the field during the process, the use of plastic adhesive drapes impregnated with antiseptics is accepted to facilitate the fixation of said surgical drapes

Perioperative hyperoxygenation. Recommendation 36.The use of high fractions of inspired oxygen (>80%) is not recommended in general anesthesia.

Maintained patient body temperature. Recommendation 37.Perioperative monitoring of core temperature is recommended in all major surgical procedures lasting >30 min.

It is recommended to apply physical measures in order to maintain core temperature ≥36 °C in all major surgical procedures lasting >30 min (except in cardiac surgery during extracorporeal circulation, in a controlled hypothermic situation).

The exclusive or combined use of hot air blankets, thermal mats, systems for heating liquids for infusion or irrigation of cavities to 37 °C, and systems for heating laparoscopic gases is recommended. It is recommended to apply body temperature maintenance systems from before the intervention until immediate post-op in the recovery room.

Perioperative glycemic control. Recommendation 38.‘Non-strict’ control of perioperative blood glucose levels is recommended in diabetic and non-diabetic patients undergoing high-risk surgery. Target: levels below 180 mg/dL. In cardiac surgery, strict perioperative glycemic control is recommended in diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

Maintained blood volume. Recommendation 39.Strict control of blood volume is recommended to avoid both the deficit and excess of extracellular volume, taking into account the individual characteristics of the patient and their cardiovascular situation.

Wound protectors-retractors. Recommendation 40. The use of double-ring plastic retractors is recommended in clean-contaminated and contaminated surgery laparotomy and in the thoracotomy of cardiac surgery with implants.

Surgical coverage. Recommendation 41.Surgical coverage can be performed with reusable or disposable material.

Cavity irrigation with physiological serum. Recommendation 42. There is no evidence that cavity irrigation increases or decreases SSI. Moderate lavage of cavities is acceptable to remove clots and detritus.

Irrigation of cavities with antiseptic solutions. Recommendation 43.Irrigation of surgical cavities with aqueous antiseptic solutions is not recommended.

Irrigation of cavities with antibiotic solutions. Recommendation 44.Irrigation of surgical cavities with antibiotic solutions is not recommended.

Wound irrigation with physiological serum. Recommendation 45.There is evidence in favor of irrigating the surgical wound with a moderate amount of pressurized saline solution at the end of the intervention.

Wound irrigation with antiseptic solutions. Recommendation 46.Surgical wound irrigation with low-concentration aqueous povidone-iodine solution (<1%) is suggested, particularly in clean and clean-contaminated surgery.

Wound irrigation with antibiotic solutions. Recommendation 47.Irrigation of the surgical wound with antibiotic solutions is not recommended.

Antimicrobial-coated sutures. Recommendation 48.The use of antimicrobial-coated sutures is suggested for the closure of the surgical wound, especially in clean surgery, in situations in which the use of absorbable sutures is indicated. The available evidence indicates that its effect is more evident for braided suture material (polyglactin) than for monofilament (polydioxanone).

Glove changes during surgery. Recommendation 49.It is suggested to change gloves under the following circumstances: every 90 min during the procedure (external pair if double gloves are used); when the surgical field has been contaminated; at the completion of an anastomosis; when moving from a contaminated-dirty area to a clean area; before handling a prosthesis; and before closure of the surgical wound. In the case of trauma surgery, also after placing the surgical field and before cementation.

Change of surgical and auxiliary material before wound closure. Recommendation 50.A change of surgical instruments and auxiliary instruments (aspirator terminals, electric scalpel, surgical light handles) is suggested before wound closure in clean-contaminated, contaminated and dirty surgery.

Prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy. Recommendation 51.The use of negative pressure devices on closed wounds is suggested in patients at high risk of incisional infection or seroma formation, especially in cardiac and orthopedic surgery with implants and in arterial surgery in the inguinal region.

Surgical wound coverage. Recommendation 52.A conventional dressing is recommended to cover the wound for 48 h.

Postoperative shower. Recommendation 53.It is recommended that patients start showering 48 h after surgery, with soap and water, leaving the wound uncovered afterwards.

ConclusionThe recommendations presented aim to adapt the scientific evidence and international guidelines to the reality of care in our country in any type of surgery. The 10 prioritized recommendations should be included in hospital bundles for the prevention of postoperative infection. Bundles can be designed for surgical specialties with exclusive measures, for example, perioperative glycemic control in cardiac surgery or S. aureus screening in orthopedic trauma surgery.

Given the finding that clinical practice guidelines have intrinsic implementation defects,4 the OIC intends to accompany these recommendations with an implementation plan that involves the surgical teams in their application. Strategies for translating evidence into practice include ‘the 6 Es’, which advises developing evidence-based, easy-to-implement measures, while engaging staff to use them by establishing a training plan to educate them, executing changes and evaluating the results.29–32

The reduction of postoperative infection is a team effort that must cover the entire perioperative period. Surgical teams, with their core of perioperative nurses, anesthesiologists and specialist surgeons, should be the leaders of change. Based on the instruments provided by this implementation plan,33 these teams can select and group the prioritized measures into systematized packages or bundles to be included on surgical patient safety checklists. Surgical teams must work in coordination with other hospital units related with surgical infection prevention (infectious diseases, preventive medicine, pharmacy) with the common objective to improve the surgical process and reduce the SSI rate.

| Ramón | Adalia Bartolomé | Servicio de Anestesiología y Reanimación. | Hospital del Mar. Barcelona | Universitat de Barcelona |

| Gerardo | Aguilar | Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos de Anestesiología. | Hospital Clínic Universitari de València | Universitat de València |

| Cesar | Aldecoa | Servicio Anestesiología y Cuidados Críticos Quirúrgicos | Hospital Universitario Río Hortega. Valladolid | |

| Bader | Al-Raies Bolaños | Servicio Angiología y Cirugía Vascular. | Hospital de Manises | |

| Javier | Arias Díaz | Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Madrid | Universidad Complutense de Madrid | |

| Antonio | Barrasa Shaw | Servicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva | Hospital Vithas Valencia 9 de octubre | Universidad Cardenal Herrera |

| Saturnino | Barrena Delfa, | Servicio de Cirugía Pediátrica | Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid | |

| M. Estrella | Blanco Cañibano | Servicio de Angiologia y Cirugía Vascular | Hospital Universitario Guadalajara | |

| Elena | Bravo Brañas | Servicio de Cirugía Plástica y Unidad de Quemados | Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid | |

| Almudena | Burillo | Servicio de Microbiología Clínica. Enfermedades Infecciosas | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid | Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Gregorio Marañón |

| Jacobo | Cabañas Montero | Servicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva | Hospital General Universitario Ramón y Cajal | Universidad de Alcalá de Henares |

| José Luis | Cebrián Carretero | Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial | Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid | Universidad Autónoma de Madrid |

| Manuel | Chamorro Pons | Servicio de Cirugía Maxilofacial | Hospital Ruber Quirón Juan Bravo | |

| Rousinelle | da Silva Freitas | Servicio de Neurocirugía | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla. Santander | |

| Fernando | de la Portilla de Juan | Unidad de Coloproctología | Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío. Sevilla | Universidad de Sevilla |

| Agustín | del Cañizo López | Servicio de Cirugía Pediátrica | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid | |

| Javier | Die Trill | Sección de Cirugia General y Digestiva. Unidad de Coloproctologia. | Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal. Madrid | |

| Eva Esther | Domínguez Amillo | Servicio de Cirugía Pediátrica. | Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Madrid | |

| María | Fanjul Gómez | Servicio de Cirugía Pediátrica | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid | |

| Carlos | Ferrando | Departamento de Anestesiología y Cuidados Críticos | Hospital Clínic. Barcelona | Institut D'investigació August Pi i Sunyer. Barcelona. |

| Salvador | Florit López | Servicio de Angiología y Cirugía Vascular | Fundació Althaia. Xarxa Assistencial i Universitària de Manresa. | |

| Juan | García-Armengol | Centro Europeo de Cirugía Colorrectal. Unidad de Coloproctología | Hospital Vithas Valencia 9 de Octubre | |

| Maria Elena | Garcia Garcia | Área quirúrgica. | Hospital Universitario de Burgos | Universidad de Burgos |

| Carlos | García Palenciano | Servicio de Anestesiología y Reanimación | Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca. Murcia | |

| Manuel | Gómez Cervantes | Servicio de Cirugía Pediátrica. | Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Madrid | |

| Francisco Javier | Gómez-Romero | Unidad de Investigación. | Gerencia de Atención Integrada de Ciudad Real. | Universidad de Castilla La Mancha. |

| Rafael | Gonzalez de Castro | Unidad de Reanimación del Servicio de Anestesiología | Hospital Universitario de León | |

| Jaime | Jimeno Fraile | Servicio de Cirugía General | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla | Universidad de Cantabria |

| Montserrat | Juvany | Servicio de Cirugía General | Hospital General de Granollers | |

| José | López-Menéndez | Servicio de Cirugía Cardíaca de adultos | Hospital General Universitario Ramón y Cajal. Madrid | |

| Alba | Manuel Vázquez | Servicio de Cirugía General | Hospital Universitario de Getafe. Madrid | |

| Oliver | Marin-Peña | Servicio de Cirugia Ortopedica y Traumatologia | Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor. Madrid | |

| Esteban | Martín Antona | Servicio de Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo. | Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Madrid | Universidad Complutense de Madrid. |

| Rafael | Martínez Nogueras | Servicio de Medicina Preventiva y Salud Pública | Hospital Universitario de Jaén | |

| Juan Carlos | Martínez Pastor | Servicio Cirugía ortopédica y Traumatología | Hospital Clínic. Barcelona | |

| Emilio | Maseda | Servicio de Anestesiología y Reanimación | Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid | |

| José | Medina-Polo | Departamento de Urología | Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre. Madrid | |

| Xosé Manuel | Meijome Sánchez | Gerencia de Asistencia sanitaria del Bierzo-GASBI | ||

| Estela | Membrilla Fernández | Servicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva | Hospital del Mar. Barcelona | Universitat Pompeu Fabra |

| Rosario | Merino Ruiz | Àrea Quirúrgica. | Hospital San Agustín. Linares. Jaén | |

| Javier | Miguelena-Hycka | Servicio de Cirugía Cardiaca de Adulto | Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal. Madrid | |

| Florencio | Monje Gil | Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial | Hospital Universitario de Badajoz | |

| Carlos A. | Morales Pérez | Servicio de Cirugía Cardiovascular | Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (HUCA) | |

| Christian | Muñoz-Guijosa | Servicio de Cirugía Cardíaca. | Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol. Badalona | Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona |

| Javier | Ordóñez | Servicio de Cirugía Pediátrica. | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid | |

| Gloria | Ortega Pérez | Servicio de Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo. | MD Anderson Cancer Center. Madrid | |

| Rosa María | Paredes Esteban | Servicio de Cirugía Pediátrica | Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba | |

| Antonio L. | Picardo Nieto | Servicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva | Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía. San Sebastián de los Reyes. Madrid | Universidad Europea de Madrid |

| Fernando | Ramasco Rueda | Jefe de Sección de Anestesiología y Reanimación. | Hospital Universitario de La Princesa. Madrid | |

| María Luisa | Reyes Díaz | UGC Cirugía General y Aparato Digestivo | Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío. Sevilla | |

| Vicente | Roig Pérez | Coordinación y desarrollo de proyectos corporativos. | Grupo Ribera | |

| Luis | Sánchez-Guillén | Servicio de Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo | Hospital General Universitario de Elche | Universidad Miguel Hernández. Elche. |

| Cristina | Sánchez-Viguera | Servicio de Neurocirugía. | Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga. | |

| Maite | Serrano Alonso | Servicio de Cirugía Plástica y Unidad de Quemados | Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid | |

| Alejandro | Suárez -de -la -Rica | Servicio de Anestesiología y Reanimación | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla. Santander | |

| Gonzalo | Tamayo Medel | Unidad de Reanimación. Servicio de Anestesiología y Reanimación | Hospital Universitario Cruces (Bizkaia) | |

| Víctor | Turrado-Rodríguez | Servicio de Cirugía Gastrointestinal | Hospital Clínic de Barcelona | |

| Marina | Varela Durán | Servicio Anestesiología y Reanimación | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra | Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Galicia Sur. |

| Vincenzo | Vigorita | Unidad de Coloproctología. Departamento de Cirugía General y Digestivo | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo, Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro | Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Galicia Sur. |

| Ramon | Vilallonga | Unidad de Endocrino-Metabólica y Bariátrica. | Hospital Univisitario Vall d'Hebrón, Campus Barcelona | Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona |

The names of the members of the Surgical Location Infection Prevention Program Working Group of the Observatory of Infection in Surgery are listed in Appendix A.