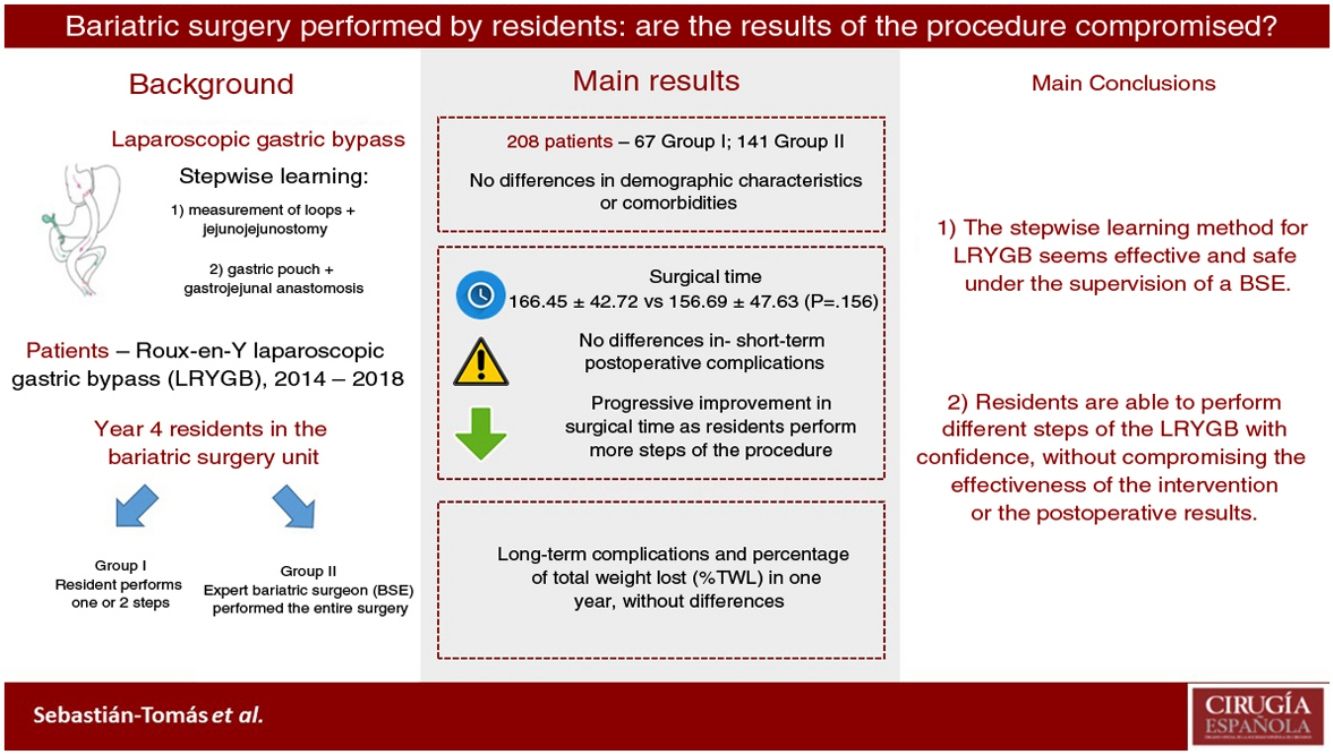

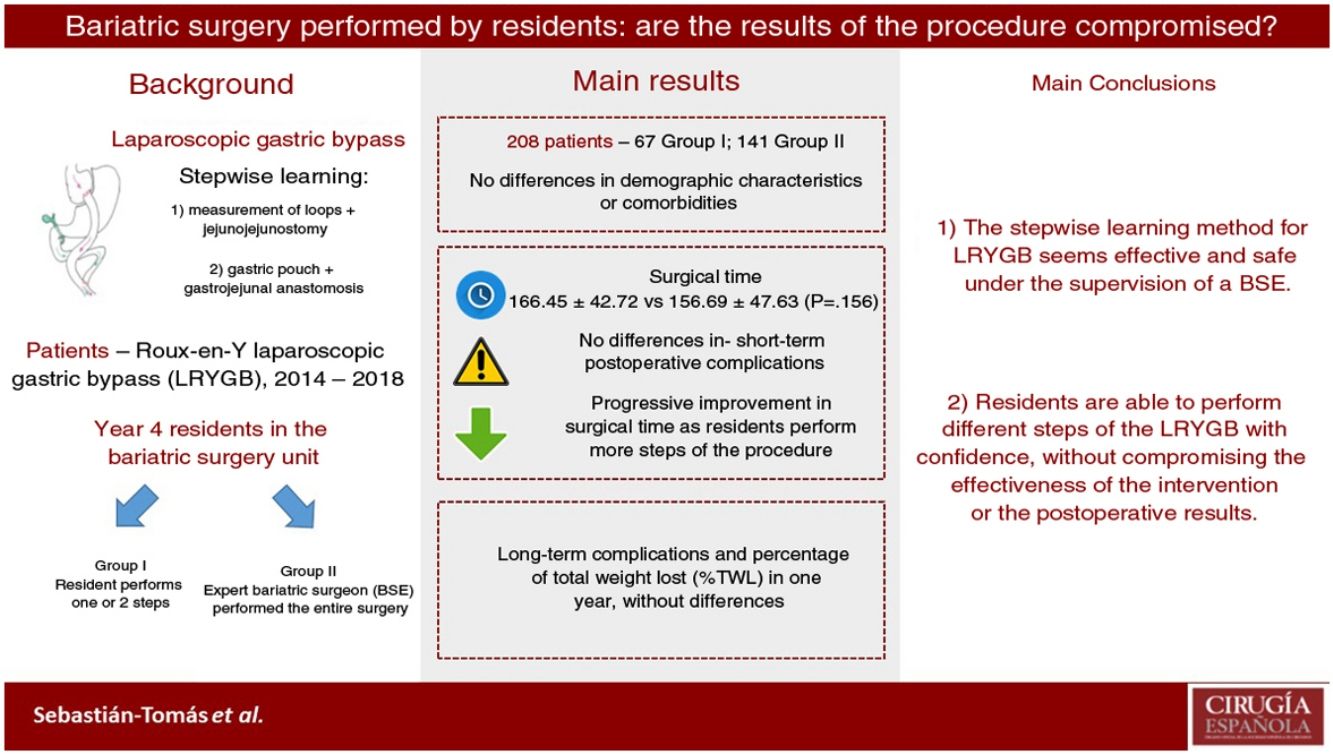

Laparoscopic bariatric procedures such as laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) are technically demanding and require a long learning curve. Little is known about whether surgical resident (SR) training programs to perform these procedures are safe and feasible. This study aims to evaluate the results of our SR training program to perform LRYGB.

MethodsWe designed a retrospective study including patients with LRYGB between January 2014 and December 2018, comparing SR results to experienced bariatric surgeons (EBS). In our country, SR have a five-year surgical formative period, and in the fourth year they are trained for 6 months in our bariatric surgery unit, from January to June. In the beginning, they perform different steps of this procedure, to finally complete an LRYGB. We collected demographic data, comorbidities, intraoperative outcomes, and postoperative complications and outcomes after a one-year follow-up.

ResultsTwo hundred and eight patients were eligible for inclusion: 67 in group I (SR), and 141 in group II (EBS). Both groups were comparable. There was no statistically significant difference in operating time (166.45 min in group I vs. 156.69 min in group II; P = 0.156). Conversion to open surgery, hospital stay, postoperative complications, and short-term outcomes had no significant differences between the two groups. There was no mortality registered during this period.

ConclusionImplementation of LRYGB stepwise learning as part of an SR training program is safe, and results are comparable to EBS, without loss of efficiency. Therefore, it is feasible to train SR in bariatric surgery under EBS supervision.

El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar los resultados de nuestro programa de formación de residentes para la realización de bypass gástrico laparoscópico en Y de Roux (BGLYR).

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo en el que se incluyeron pacientes a los que se les realizó un BGLYR en nuestro centro durante el período comprendido entre enero de 2014 y diciembre de 2018. Los residentes de cuarto año de nuestro centro realizaron progresivamente distintos pasos de la intervención siempre tutorizados por cirujanos bariátricos expertos (CBE). Se compararon los resultados obtenidos en las intervenciones en las que el residente ha realizado algún paso o la totalidad del BGLYR (grupo I), con aquellas realizadas en su totalidad por CBE (grupo II). Se analizaron datos demográficos de los pacientes, comorbilidades, resultados intraoperatorios, morbimortalidad postoperatoria y resultados al año de la intervención.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 208 pacientes en el estudio, 67 en el grupo I y 141 en el grupo II. Ambos grupos fueron comparables. No se objetivaron diferencias significativas en el tiempo operatorio (166,45 min en el grupo I vs. 156,69 min en el grupo II; p = 0,156). La conversión a cirugía abierta, la estancia hospitalaria y la morbilidad postoperatoria tampoco presentaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas. No hubo mortalidad durante este período. Los resultados tras el primer año fueron similares en ambos grupos.

ConclusionesLa realización de distintos procedimientos del BGLYR por residentes es segura y no compromete la efectividad ni los resultados postoperatorios, siempre que se realice bajo la supervisión de un CBE.

The prevalence of obesity continues to increase around the world, and bariatric surgery is considered the most effective treatment to achieve sustained weight loss in patients with morbid obesity.1 Among the surgical techniques available, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) continues to be one of the most commonly used procedures.2 LRYGB is considered a demanding technique for several reasons, including the physical constitution of the subjects undergoing the procedure, the complexity of laparoscopic procedures, and the risk of complications in this group of patients.3

Within our healthcare system, the challenge for hospitals that train resident interns is to provide them with the best and most complete training, without negatively affecting healthcare results. This goal is more difficult to achieve when it involves learning technical and/or surgical procedures, as in the case of surgical specialties.

In the process of learning a surgical technique, performance tends to improve as experience is gained. The graphic representation of this phenomenon is the ‘learning curve’.4,5 In bariatric surgery, the most commonly studied procedure in this regard is the LRYGB. Several authors have established that the number of cases required to complete the LRYGB learning curve is between 75 and 100 procedures.6,7 Lublin et al.8 establish that the number of cases after which the surgeon feels confident to perform an LRYGB is around 20–25.

Multiple learning systems have been described: ex vivo preoperative practice, warm-up before the procedure, detailed review of the technique before and during the operation, etc.9 However, it seems that a stepwise learning system is more widely accepted.10–12 In this system, the surgeon-in-training performs progressively more complex steps of the same procedure until she/he is able to carry it out in its entirety. Our teaching and learning system follows this model, always under the supervision of bariatric surgery experts (BSE). The objective of this study is to analyze the results of our resident training program in LRYGB.

MethodsPatientsOur retrospective study included patients who underwent LRYGB, performed by our unit from January 2014 to December 2018. All patients gave their written informed consent for the surgical procedure. The study was developed based on the latest version of the Helsinki Declaration, and all the rules established by the Ethics Committee of our center have been followed. Since it is a retrospective study, informed consent was not obtained for participation in the study.

All patients met the indications of the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders to be candidates for bariatric surgery (BMI >40 kg/m2 or BMI >35 kg/m2 with comorbidities and failed medical treatment). The patients followed the standard preoperative preparation established in our protocol, which includes the exclusion of any medical or surgical contraindications, a 10% preoperative weight loss and physical exercise, a very low-calorie diet (VLCD) and the evaluation of the candidates by the multidisciplinary committee.

The patients were divided into 2 groups: Group I included patients in whom some step of the intervention had been performed by residents under the supervision of a BSE, while group II consisted of patients in whom the entire intervention was performed by one or 2 BSE. The decision to allow residents perform one or more procedures depended on the BSE and was taken at the time of the operation, based on the evaluation of the progression of the residents under constant supervision by the members of the bariatric surgery unit during the rotation. All patients had a minimum follow-up of 12 months.

Surgical techniqueTraining for our year 4 general surgery residents includes a rotation in our bariatric surgery unit from January to June. During this period, they progressively perform different parts of bariatric procedures, including the LRYGB, completing the full technique in some cases by the end of the rotation. This is always done under the supervision of BSE, who have individually performed between 150 and 300 bariatric procedures throughout the unit’s experience of more than 20 years.

Our LRYGB surgical technique basically consists of 2 parts.13

- 1

Creation of the jejunojejunal anastomosis: after identifying the Treitz angle, the loop is divided 80 cm away with a 45-mm linear stapler with 2.5 mm staple height. The alimentary limb is then measured (approximately 220 cm) to create the anastomosis by means of a mechanical side-to-side entero-anastomosis, closing the enterostomy with a continuous barbed manual suture. The mesenteric gap is closed with a continuous manual 3/0 silk suture. The presence of a common loop greater than 150 cm is confirmed, and it ascends from the inframesocolic compartment through the antecolic route.

- 2

Creation of the gastric pouch and gastrojejunal anastomosis: a gastric reservoir of about 15–30 cc (pouch or neo-stomach) is created by division and stapling of the remaining stomach around a 36F Faucher tube, to avoid recanalization to the defunctionalized stomach. The gastric pouch is created at the expense of the lesser curvature of the stomach, initiating the dissection 4–5 cm from the gastroesophageal junction, between the 2nd and 3rd transverse gastric vessels and keeping it caudal to the left gastric artery. Continuity with the digestive tract is carried out with a Roux-en-Y loop of the small intestine (alimentary limb) using mechanical side-to-side gastrojejunal anastomosis, calibrated with a linear stapler measuring 30 mm in length and 3.5 mm in staple height. Subsequently, the enterostomy is closed analogously to the anastomosis. This technique provides visualization of the lumen and helps detect possible bleeding. Once the anastomosis is created, a leak test is performed.

The demographic variables analyzed include: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score,14 history of comorbidities and previous surgeries. The intraoperative data recorded were: which surgeon performed the procedures, conversion to open surgery, and surgical time. Regarding the postoperative period, postoperative complications within 90 days were collected using the Dindo-Clavien classification,15 along with hospital stay and 90-day mortality. As short-term results, we analyzed late complications and weight loss during the first year after surgery using the percentage of total weight lost (%TWL).

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was carried out with the SPSS® v.25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Data were analyzed using the mean (standard deviation) and the median (P25-P75) in the case of quantitative variables, and absolute frequency (%) for categorical variables. Either the Student’s t test or the Mann-Whitney U test for quantitative variables was used for the analysis of the differences between groups, depending on whether they were normal or non-normal variables, and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables. A P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsDuring the study period, 243 bariatric surgeries were performed at our hospital, 208 (85.60%) of which were LRYGB, 8 (3.29%) open gastric bypass, 19 (7.82%) laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (SG), 6 (2.47%) open SG and 2 (0.82%) revision surgery.

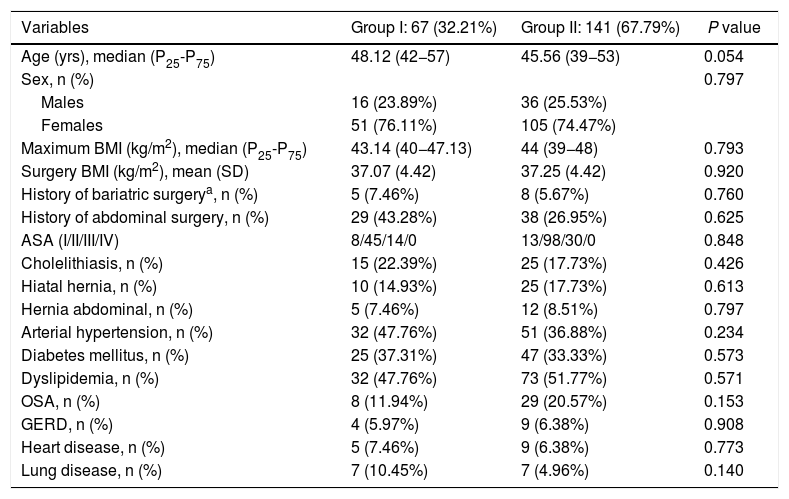

A total of 208 patients were included in the study: 67 (32.31%) in group I and 141 (67.79%) in group II. The demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The median age was 48.12 years (P25-P75 = 42−57) in group I and 45.56 years (P25-P75 = 39−53) in group II. The mean BMI at the time of the intervention was 37.93 ± 4.50 kg/m2 in group I and 38.03 ± 5.29 kg/m2 in group II. The percentage of women was 76.11% in group I and 74.47% in group II. No statistically significant differences were found for demographic characteristics or comorbidities between the patients in the two groups.

Patient demographic characteristics and comorbidities.

| Variables | Group I: 67 (32.21%) | Group II: 141 (67.79%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs), median (P25-P75) | 48.12 (42−57) | 45.56 (39−53) | 0.054 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.797 | ||

| Males | 16 (23.89%) | 36 (25.53%) | |

| Females | 51 (76.11%) | 105 (74.47%) | |

| Maximum BMI (kg/m2), median (P25-P75) | 43.14 (40−47.13) | 44 (39−48) | 0.793 |

| Surgery BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 37.07 (4.42) | 37.25 (4.42) | 0.920 |

| History of bariatric surgerya, n (%) | 5 (7.46%) | 8 (5.67%) | 0.760 |

| History of abdominal surgery, n (%) | 29 (43.28%) | 38 (26.95%) | 0.625 |

| ASA (I/II/III/IV) | 8/45/14/0 | 13/98/30/0 | 0.848 |

| Cholelithiasis, n (%) | 15 (22.39%) | 25 (17.73%) | 0.426 |

| Hiatal hernia, n (%) | 10 (14.93%) | 25 (17.73%) | 0.613 |

| Hernia abdominal, n (%) | 5 (7.46%) | 12 (8.51%) | 0.797 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 32 (47.76%) | 51 (36.88%) | 0.234 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 25 (37.31%) | 47 (33.33%) | 0.573 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 32 (47.76%) | 73 (51.77%) | 0.571 |

| OSA, n (%) | 8 (11.94%) | 29 (20.57%) | 0.153 |

| GERD, n (%) | 4 (5.97%) | 9 (6.38%) | 0.908 |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 5 (7.46%) | 9 (6.38%) | 0.773 |

| Lung disease, n (%) | 7 (10.45%) | 7 (4.96%) | 0.140 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; SD: standard deviation; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; BMI: body mass index; OSA: obstructive sleep apnea.

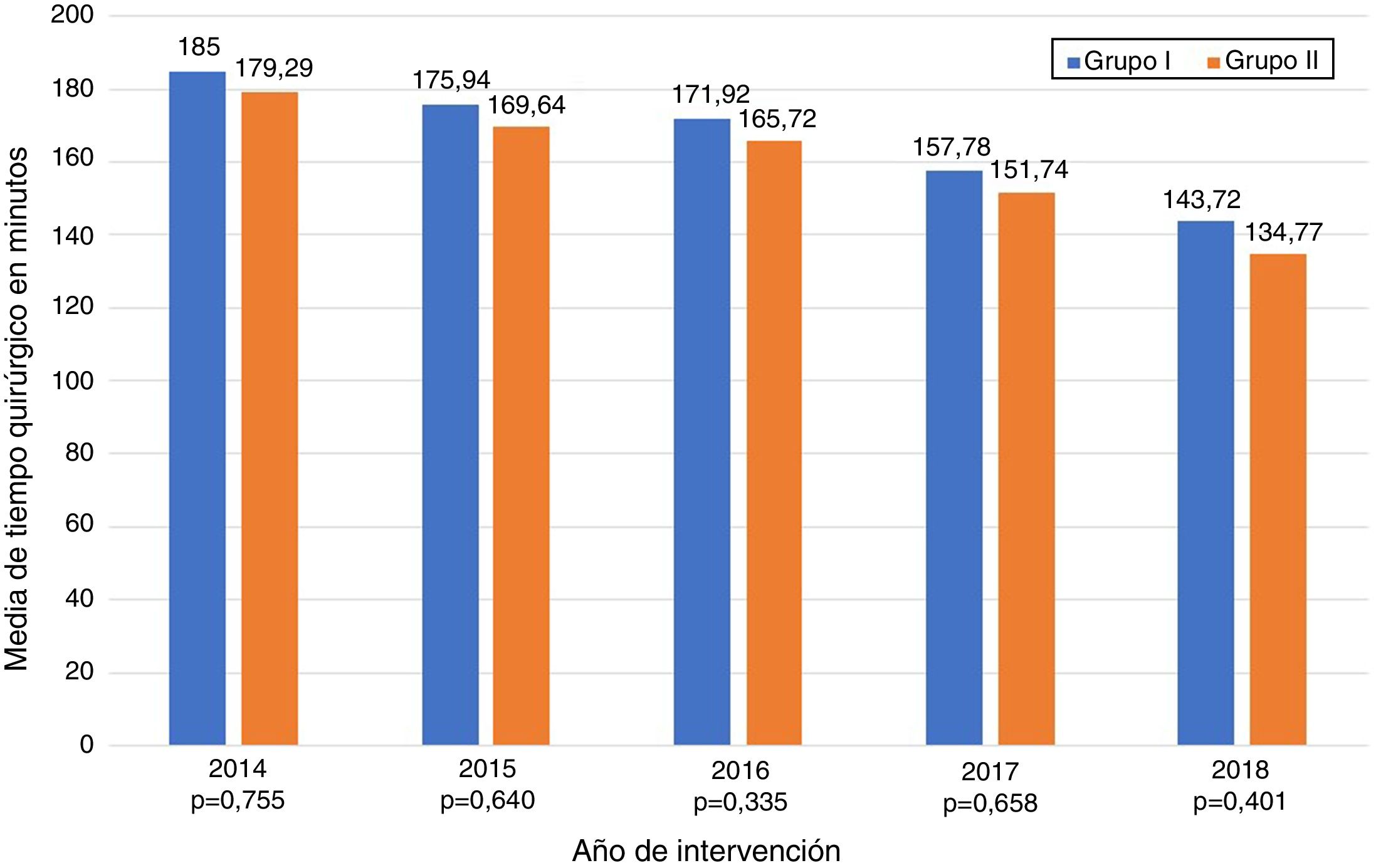

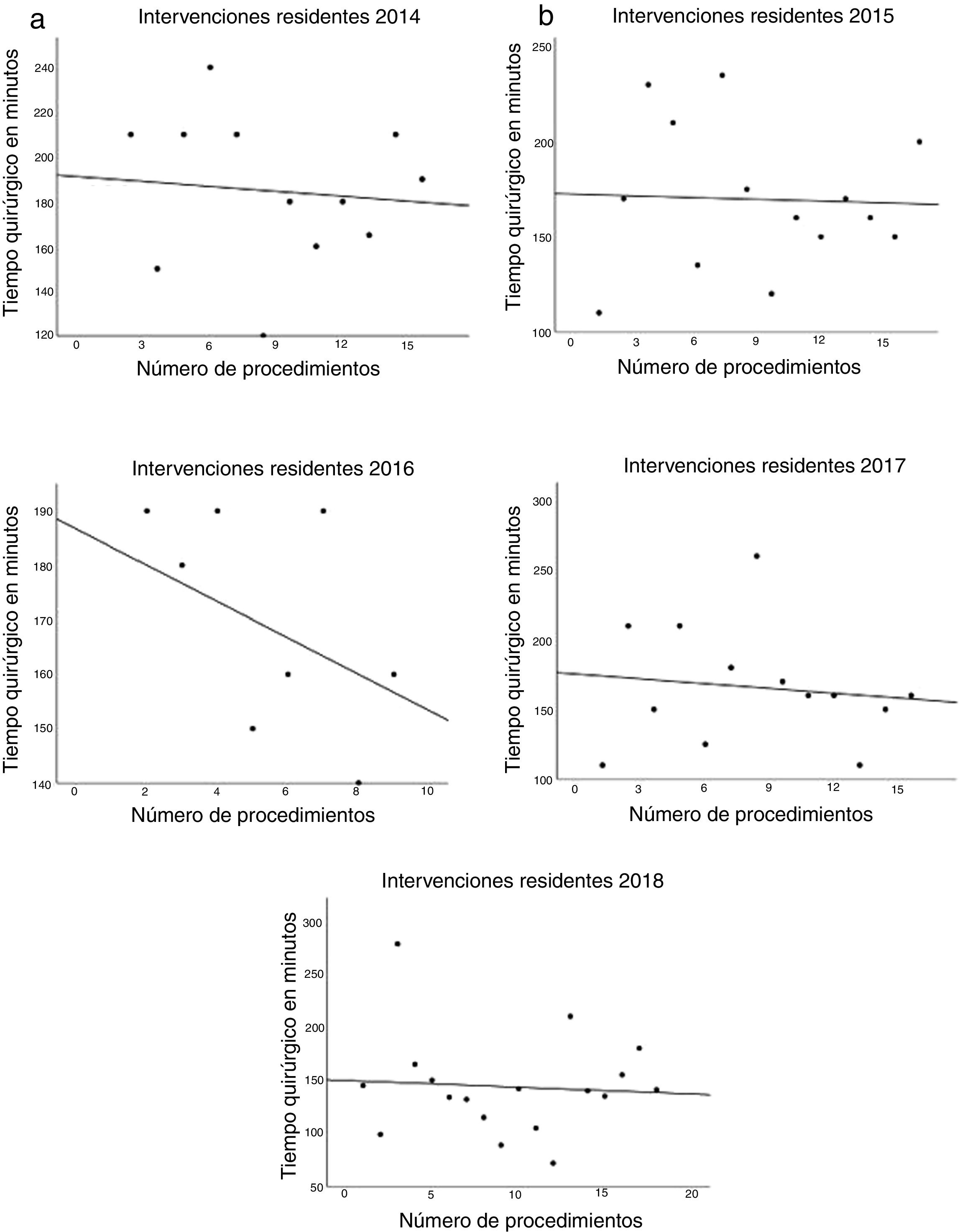

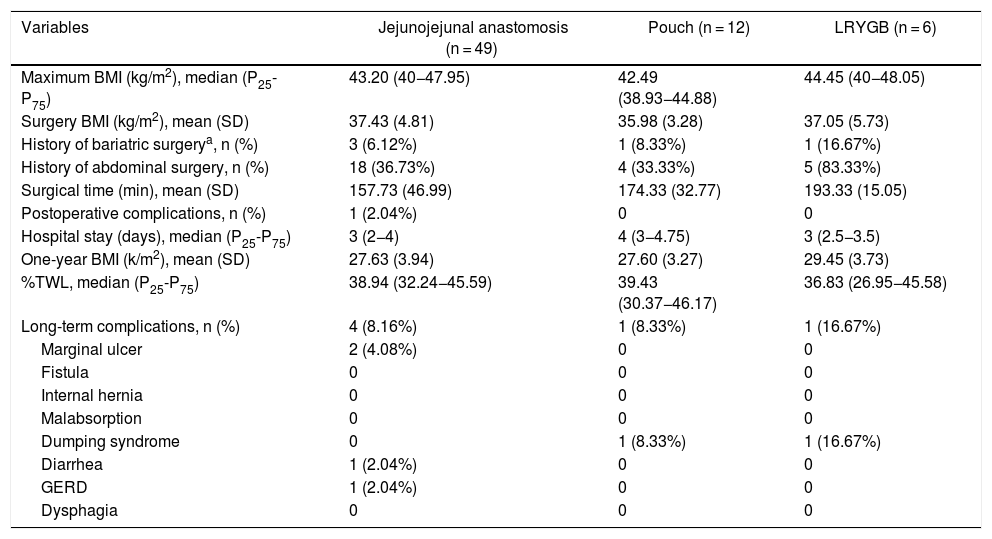

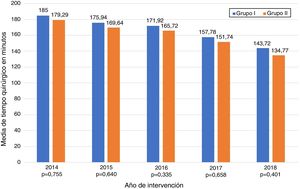

The data referring to the surgery are shown in Table 2. The residents successfully completed 47/49 (95.92%) jejunojejunal anastomoses, 11/12 (91.66%) gastric pouches and the 6 complete LRYGB, while in the remaining 3 cases the BSE had to end the procedure due to technical difficulties (creating a new jejunojejunal anastomosis in one case due to technical defect, another due to bleeding at the time of closure of the mesenteric gap after creating the jejunojejunal anastomosis, and the third because it was impossible to complete the closure of the defect of the gastrojejunal anastomosis). These patients were included in group I since, in all 3 cases, the completion of said step by the BSE was not carried out from the beginning, but rather the resident performed a large part of the procedure. There was only one conversion to open surgery due to bleeding in group II. The mean surgical time was 166.45 ± 42.72 in group I and 156.69 ± 47.63 min in group II (P = .156). Analyzed individually according to the year of surgery, there were no differences in surgical time between group I and group II (Fig. 1). A progressive decrease in surgical time was observed as the number of procedures performed by residents increased (Fig. 2).

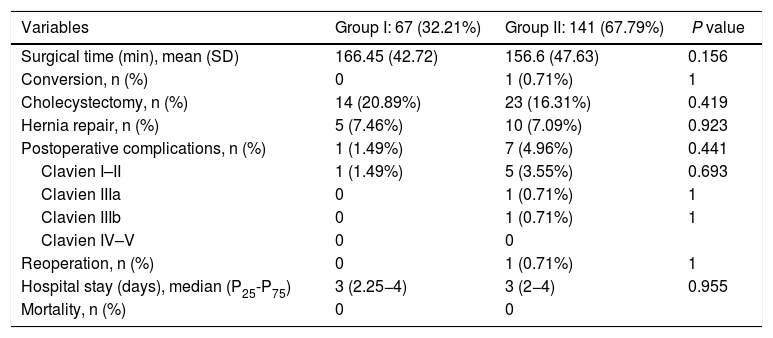

Data referring to the surgical procedure and the postoperative course.

| Variables | Group I: 67 (32.21%) | Group II: 141 (67.79%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical time (min), mean (SD) | 166.45 (42.72) | 156.6 (47.63) | 0.156 |

| Conversion, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.71%) | 1 |

| Cholecystectomy, n (%) | 14 (20.89%) | 23 (16.31%) | 0.419 |

| Hernia repair, n (%) | 5 (7.46%) | 10 (7.09%) | 0.923 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | 1 (1.49%) | 7 (4.96%) | 0.441 |

| Clavien I–II | 1 (1.49%) | 5 (3.55%) | 0.693 |

| Clavien IIIa | 0 | 1 (0.71%) | 1 |

| Clavien IIIb | 0 | 1 (0.71%) | 1 |

| Clavien IV–V | 0 | 0 | |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.71%) | 1 |

| Hospital stay (days), median (P25-P75) | 3 (2.25−4) | 3 (2−4) | 0.955 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 0 | 0 |

SD: standard deviation; Min: minutes.

The median hospital stay was 3 days (P25-P75 = 2.25−4) in group I and 3 days (P25-P75 = 2−4) in group II (P = .955). No significant differences were found regarding postoperative complications between the groups. There was one (1.49%) postoperative complication in group I and 7 (4.96%) in group II (P = .441). The most frequent complication was postoperative bleeding, and only one patient required laparoscopic reoperation in group II. The remainder were: one anastomotic leak managed with percutaneous drainage, one wound infection, and one case of pneumonia. There was no postoperative mortality during the study period. Detailed postoperative results are shown in Table 2.

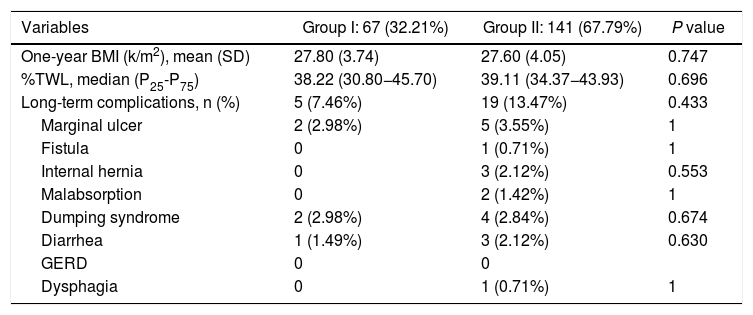

The long-term results are shown in Table 3. Mean BMI one year after the intervention was 27.80 ± 3.74 kg/m2 in group I and 27.60 ± 4.05 kg/m2 in group II (P < .747). The median %TWL one year after the intervention was 38.22 (P25-P75 = 30.80−45.70) in group I and 39.11 (P25-P75 = 34.37−43.93) in group II (P < .696). No differences were identified regarding the presence of symptoms related to malabsorption, gastroesophageal reflux, dysphagia or dumping syndrome (Table 4).

Results one year after surgery.

| Variables | Group I: 67 (32.21%) | Group II: 141 (67.79%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-year BMI (k/m2), mean (SD) | 27.80 (3.74) | 27.60 (4.05) | 0.747 |

| %TWL, median (P25-P75) | 38.22 (30.80−45.70) | 39.11 (34.37−43.93) | 0.696 |

| Long-term complications, n (%) | 5 (7.46%) | 19 (13.47%) | 0.433 |

| Marginal ulcer | 2 (2.98%) | 5 (3.55%) | 1 |

| Fistula | 0 | 1 (0.71%) | 1 |

| Internal hernia | 0 | 3 (2.12%) | 0.553 |

| Malabsorption | 0 | 2 (1.42%) | 1 |

| Dumping syndrome | 2 (2.98%) | 4 (2.84%) | 0.674 |

| Diarrhea | 1 (1.49%) | 3 (2.12%) | 0.630 |

| GERD | 0 | 0 | |

| Dysphagia | 0 | 1 (0.71%) | 1 |

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; %TWL: percent total weight lost.

Patient characteristics and results of procedures performed by residents.

| Variables | Jejunojejunal anastomosis (n = 49) | Pouch (n = 12) | LRYGB (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum BMI (kg/m2), median (P25-P75) | 43.20 (40−47.95) | 42.49 (38.93−44.88) | 44.45 (40−48.05) |

| Surgery BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 37.43 (4.81) | 35.98 (3.28) | 37.05 (5.73) |

| History of bariatric surgerya, n (%) | 3 (6.12%) | 1 (8.33%) | 1 (16.67%) |

| History of abdominal surgery, n (%) | 18 (36.73%) | 4 (33.33%) | 5 (83.33%) |

| Surgical time (min), mean (SD) | 157.73 (46.99) | 174.33 (32.77) | 193.33 (15.05) |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | 1 (2.04%) | 0 | 0 |

| Hospital stay (days), median (P25-P75) | 3 (2−4) | 4 (3−4.75) | 3 (2.5−3.5) |

| One-year BMI (k/m2), mean (SD) | 27.63 (3.94) | 27.60 (3.27) | 29.45 (3.73) |

| %TWL, median (P25-P75) | 38.94 (32.24−45.59) | 39.43 (30.37−46.17) | 36.83 (26.95−45.58) |

| Long-term complications, n (%) | 4 (8.16%) | 1 (8.33%) | 1 (16.67%) |

| Marginal ulcer | 2 (4.08%) | 0 | 0 |

| Fistula | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Internal hernia | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malabsorption | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dumping syndrome | 0 | 1 (8.33%) | 1 (16.67%) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (2.04%) | 0 | 0 |

| GERD | 1 (2.04%) | 0 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 0 | 0 | 0 |

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; Min: minutes; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; %TWL: percentage of total weight lost.

The results of our study demonstrate that residents are able to safely perform different LRYGB procedures, without compromising long-term or perioperative results. Our learning method (progressively carrying out different steps of the intervention) allows residents to acquire the necessary technical skills without altering the patient care activity.

Most importantly, we have not observed significant differences in surgical time regardless of whether the resident performs certain steps of the intervention (166.45 ± 42.72 group I vs. 156.69 ± 47.63 group II; P = .156). Longer surgical time is associated with a higher rate of postoperative complications16,17 and has been proposed as a quality marker in bariatric surgery.17 Most of the studies published in the literature show significant differences in operative time in the procedures involving residents or surgeons-in-training.10,18–25 The Barbat et al.20 study has been the largest series (477,670 patients) and established a mean difference of 22.3 min. When we analyzed the subgroups of patients in whom residents created the gastric pouch and the gastrojejunal anastomosis or the complete LRYGB, we found an increase in surgical times of 17.73 and 36.73 min, respectively. As the small number of patients included in these subgroups is an important limitation, we have not determined whether there are statistically significant differences compared to the group of patients operated on by BSE. We have also found that surgical time decreased as the number of procedures performed by residents increased during their rotation in the unit. This occurred in all cases to a greater or lesser extent (Fig. 2), which coincides with the results of other studies on the subject.12,25,26

In terms of postoperative complications, there was greater variability in the results. Some authors defend that the rate of postoperative complications, especially minor complications, is higher when surgeons-in-training actively participate in surgery.10,19,20,22–24 Others, however, find no differences, or these are not clinically relevant.21,27,28 In our series, the complication rate was not higher in the group where the resident performed the LRYGB, either partially or totally. This may be due to the fact that a resident always actively participates in all surgeries, regardless of whether or not they perform a procedure of the operation, and this does not lead to an increase in postoperative complications according to what is established in the literature for LRYGB.29–31

The study, which also analyzed complications and %TWL one year after surgery, shows no statistically significant differences between groups and concurs with the results of the available literature.1,32–36 There are similar data that have also been published in other articles, such as a similar percentage of excess weight lost one year after surgery between the group of patients treated in part by residents and the group of patients treated by BSE.18,37

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective study and therefore has a higher risk of selection bias and confusion. Second, the number of patients included is low. The data show that the creation of the jejunojejunal anastomosis is the procedure most frequently performed by residents, and the number of pouches or complete LRYGB is lower, which is a limitation when analyzing the results. The skills of residents are inevitably variable; however, these differences are attenuated by the fact that all residents spend their rotation in the Bariatric Surgery Unit during the same training period. The study also does not contemplate the inevitable help that the resident receives from the BSE while performing a certain step of the surgery, nor does it analyze the participation of other professionals, such as nurses or anesthetists, in the treatment process.

In conclusion, our data show that the stepwise learning method seems effective and safe. In this manner, residents are able to perform different LRYGB procedures with confidence and without compromising the effectiveness of the intervention or postoperative results. However, more prospective studies are necessary to confirm these results.

AuthorshipStudy design and concept: Sebastián-Tomás JC, Navarro-Martínez S, Diez-Ares JA and Peris-Tomás N.

Data collection: all authors.

Statistical analysis: Sebastián-Tomás JC.

Final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

FundingNo funding was needed to conduct this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Ethics approvalAll procedures were conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of our hospital and the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consentAs it is a retrospective study, no informed consent was obtained from patients.

The authors would like to thank all the specialists who have developed the Unit over the years and the residents who have rotated through the Unit.

Please cite this article as: Sebastián-Tomás JC, Navarro-Martínez S, Peris-Tomás N, Díez-Ares JÁ, Gonzálvez-Guardiola P, Periañez-Gómez D, et al. Realización de procedimientos bariátricos por residentes de cirugía general. ¿Compromete la efectividad de la intervención y los resultados postoperatorios? Cir Esp. 2021;99:200–207.

The results of this study were selected for presentation at the 24th IFSO World Congress 2019, held in Madrid, and the 22nd National Surgery Congress 2019, held in Santander.