Muscle symptoms, with or without elevation of creatine kinase are one of the main adverse effects of statin therapy, a fact that sometimes limits their use. The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical characteristics of patients treated with statins who have complained muscle symptoms and to identify possible predictive factors.

Patients and methodsA cross-sectional one-visit, non-interventional, national multicenter study including patients of both sexes over 18 years of age referred for past or present muscle symptoms associated with statin therapy was conducted. 3845 patients were recruited from a one-day record from 2001 physicians.

ResultsMyalgia was present in 78.2% of patients included in the study, myositis in 19.3%, and rhabdomyolysis in 2.5%. Patients reported muscle pain in 77.5% of statin-treated individuals, general weakness 42.7%, and cramps 28.1%. Kidney failure, intense physical exercise, alcohol consumption (>30g/d in men and 20g/d in women) and abdominal obesity were the clinical situations associated with statin myopathy.

ConclusionsMyalgia followed by myositis are the most frequent statin-related side effects. It should be recommended control environmental factors such as intense exercise and alcohol intake as well as abdominal obesity and renal function of the patient treated with statins.

Los síntomas musculares, con o sin elevación de creatincinasa, son uno de los principales efectos adversos del tratamiento con estatinas, hecho que en ocasiones limita su uso. El objetivo del presente estudio ha sido evaluar las características clínicas de los pacientes tratados con estatinas que han presentado síntomas musculares, e identificar los posibles factores predictores.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio transversal de una sola visita, no intervencional, multicéntrico nacional, que incluyó pacientes de ambos sexos mayores de 18 años de edad que habían presentado o presentaban síntomas musculares asociados a la terapia con estatinas. Participaron 2.001 médicos que aportaron los datos clínicos de un total de 3.845 pacientes.

ResultadosLa mialgia estuvo presente en el 78,2% de los pacientes incluidos en el estudio, la miositis en un 19,3% y la rabdomiólisis en el 2,5%. Los pacientes refirieron dolor muscular en el 77,5% de los casos, debilidad general en el 42,7% y calambres en el 28,1%. La insuficiencia renal, el ejercicio físico intenso, el consumo de alcohol (>30g/d en varón y 20g/d en mujer) y la obesidad abdominal fueron las situaciones clínicas asociadas con la miopatía por estatinas.

ConclusionesLa mialgia seguida de la miositis son los efectos musculares más frecuentes relacionados con el uso de estatinas. Debe recomendarse el control de factores ambientales como el ejercicio físico intenso y la ingesta alcohólica, así como la obesidad abdominal y la función renal del paciente tratado con estatinas.

Statins form part of the basic pharmacological approach in cardiovascular prevention1 and have an excellent safety profile. They are, however, not free of undesirable effects,2 and muscular disorders with or without creatinine (CK) elevation must be considered and monitored.3 Muscular symptoms associated with statin therapy present variable incidence rates and can be the cause of a loss of adherence or discontinuity of treatment in two thirds of all cases in the first two years of treatment,4–7 resulting in a significant loss of cardiovascular prevention.8

The clinical spectrum of muscular symptoms is broad and includes muscle pain, stiffness or cramps. They are often referred to as “myalgia” and are usually symmetrical, although they can be localised, occasionally accompanied by loss of strength and usually without CK elevation. In randomised clinical studies, myalgia is usually present in 1–5%,9–11 but observational studies show that it tends to be more common in clinical practice. In the study entitled Effects of Statins on Muscle Performance (STOMP), muscular symptoms were found in 9.4% of the cases treated with 80mg of atorvastatin and only in 4.6% of the placebo group.12 In the PRIMO study, an observational study in around 8,000 dyslipidaemia patients treated as outpatients with high doses of statins, 10.5% presented muscular symptoms, with muscle pain being the main obstacle to the conduct of even moderate normal activities.13 Muscle pain also tends to be the most commonly described symptom in patients during the first month of pharmacological treatment.14

However, 90% of patients with muscular problems apparently associated with treatment with a specific statin are capable of tolerating a different statin. This suggests that the problem cannot be generally attributed to all statins, or that it may have multiple causes.7 This study, entitled Defining the Onset of Statin-associated Myopathy (DAMA), was conducted to evaluate the clinical characteristics of patients treated with statins who presented muscular symptoms, and to identify possible predictive factors.

Patients and methodsThe DAMA study is a cross-sectional, one-visit, non-interventional, national, multi-centre study including patients of both sexes over 18 years of age with past or present muscle symptoms associated with statin therapy. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute Hospital del Mar d’Investigacions Mèdiques. The researchers followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and SOPs ensured compliance with Good Clinical Practice. All the patients signed the informed consent form to be included in the study.

Two thousand and one physicians participated, with a mean age of 50.7±8.6 years, providing clinical data from a total of 3845 patients. Of the participating physicians, 73% provided primary care and 27% were specialists (internal medicine, cardiology, endocrinology, or other).

Data was collected from each patient regarding their age, sex, toxic habits, anthropometric and biochemical parameters, including lipid profile, glomerular filtration rate and CK, associated pathologies, concomitant drug treatments, as well as data about myopathy.

According to the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI),15 myopathy is defined as any muscle sign or symptom (clinical and/or biochemical) after starting statin therapy, from mild myalgia without CK elevation to rhabdomyolysis. Thus the term myalgia refers to muscle ache or weakness or heaviness without CK elevation; myositis is defined as when muscle symptoms are accompanied by CK elevation, and lastly rhabdomyolysis is when CK levels exceeded 10,000IU/L, generally associated with myoglobinuria and kidney failure.

The data were recorded in an electronic case report form specifically designed for the DAMA study, with filters to correct possible inconsistencies or discrepancies. Moreover, once the data were entered, no other data could be added or the existing data modified.

The descriptive analysis was broken down into a central tendency, with dispersion measures and relative frequencies, including 95% confidence intervals. Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables, Student's t-test between 2 groups was used for continuous variables and ANOVA between 3 or more groups. The Mann–Whitney non-parametric U test or the Kruskal–Wallis test were used for non-normal data. In all cases, the established level of statistical significance was 0.05 bilateral. The data was analysed using the SAS statistical package, version 9.1.3 Service Pack 4.

ResultsThe 3845 patients included in the study had a mean age of 62.3±12 years and 68% were male. Sixty-three percent of the patients were in the 51–70 age group and 22% were over 70.

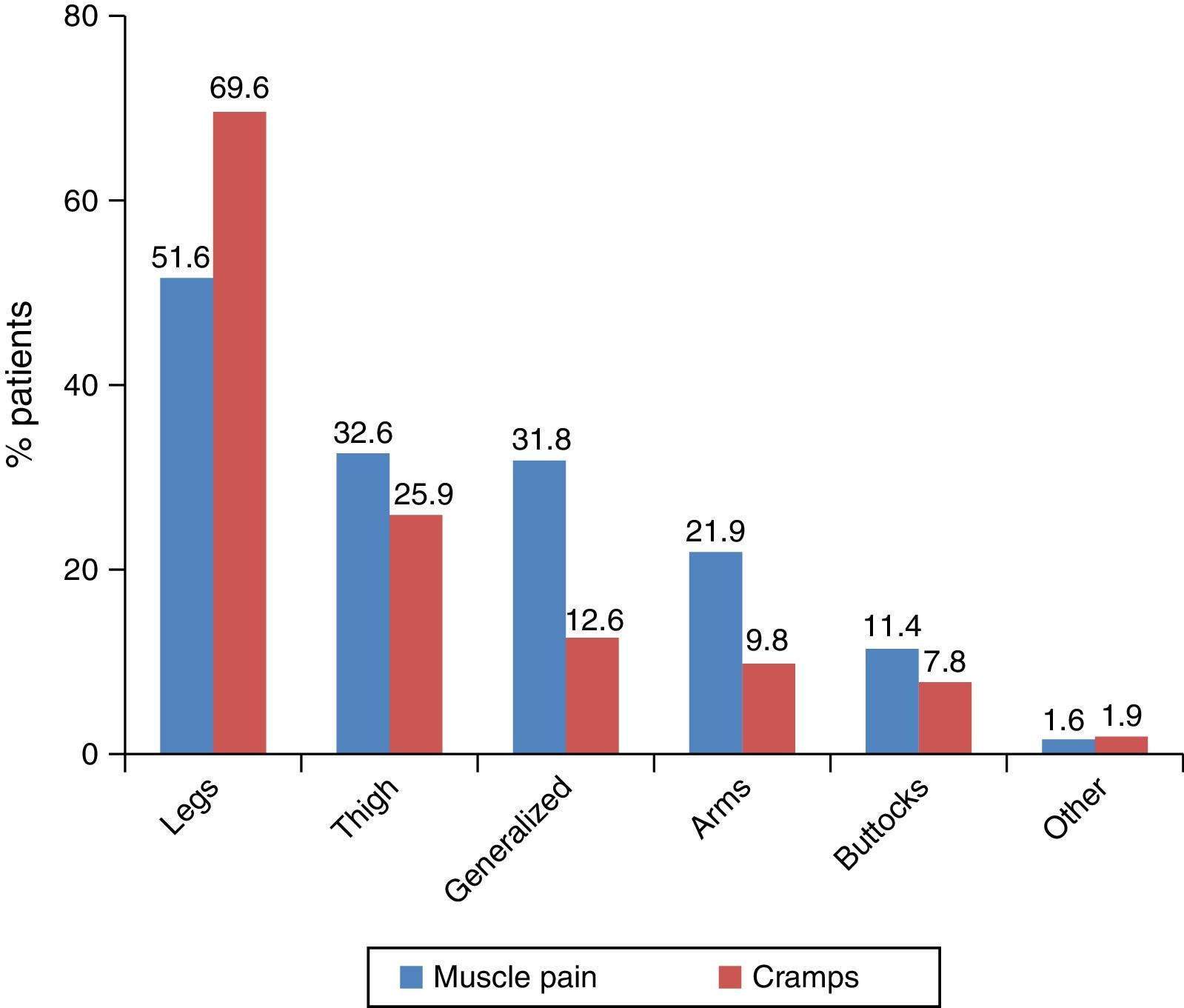

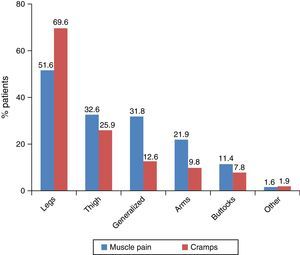

In terms of potentially statin-related muscle symptoms, 2981 patients (77.5%) presented muscle ache, of which 55.6% reported it at rest and the rest only during exercise. A total of 1642 patients (42.7%) had muscle weakness, 53.4% at rest and 46.6% only during exercise. Lastly, 1080 patients (28.1%) reported muscle cramps, 64% at rest and 36% during exercise. Fig. 1 shows the most common locations of muscle ache and cramps.

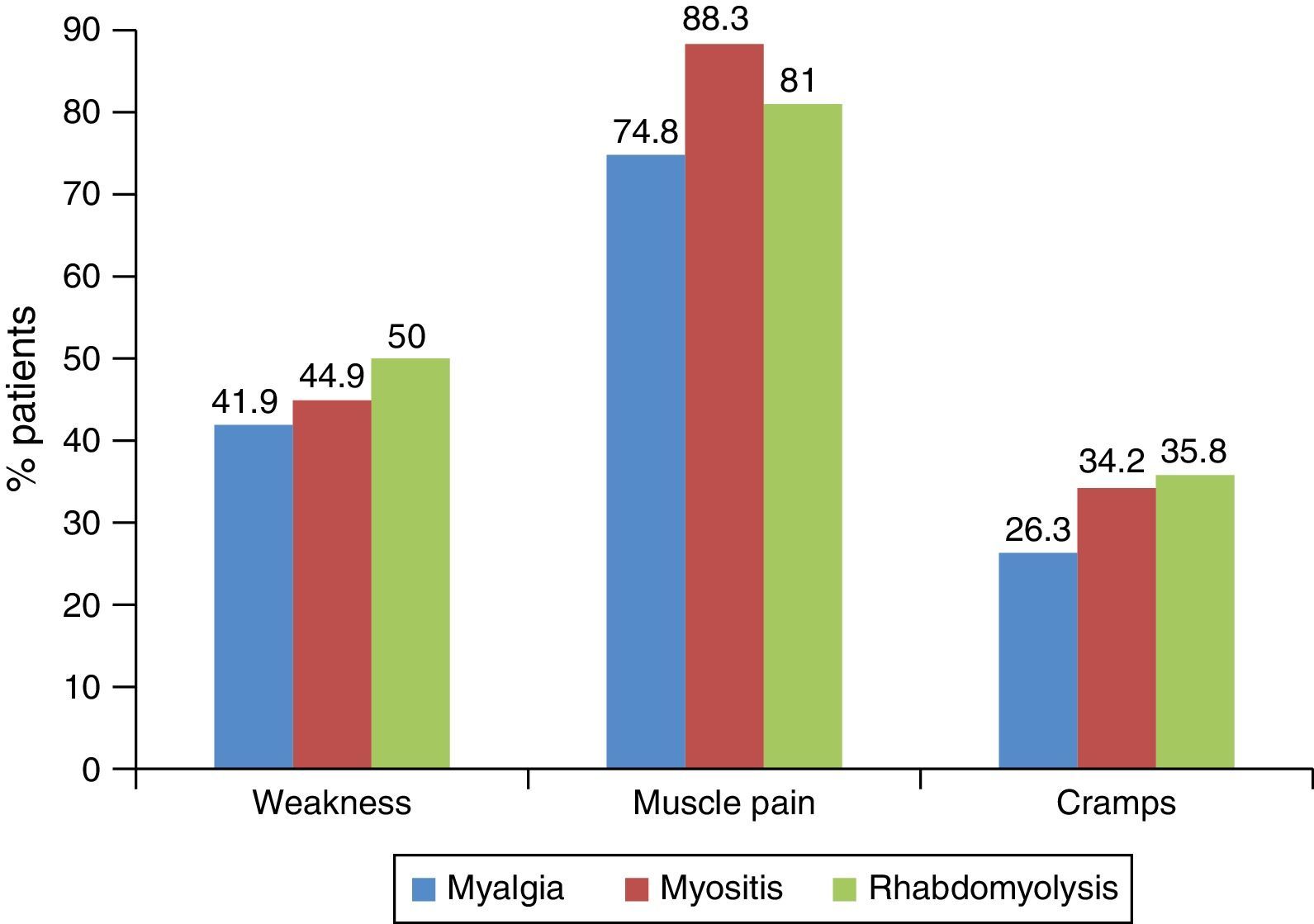

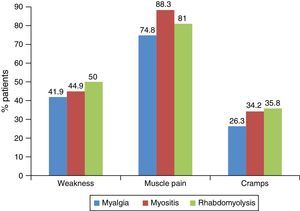

According to the severity of the myopathy, 78.2% of the patients were afflicted with myalgia, 19.3% with myositis, and 2.5% with rhabdomyolysis. Fig. 2 shows the correlation between muscle symptoms with the different clinical forms of myopathy; this association was statistically significant for the muscle ache and cramps.

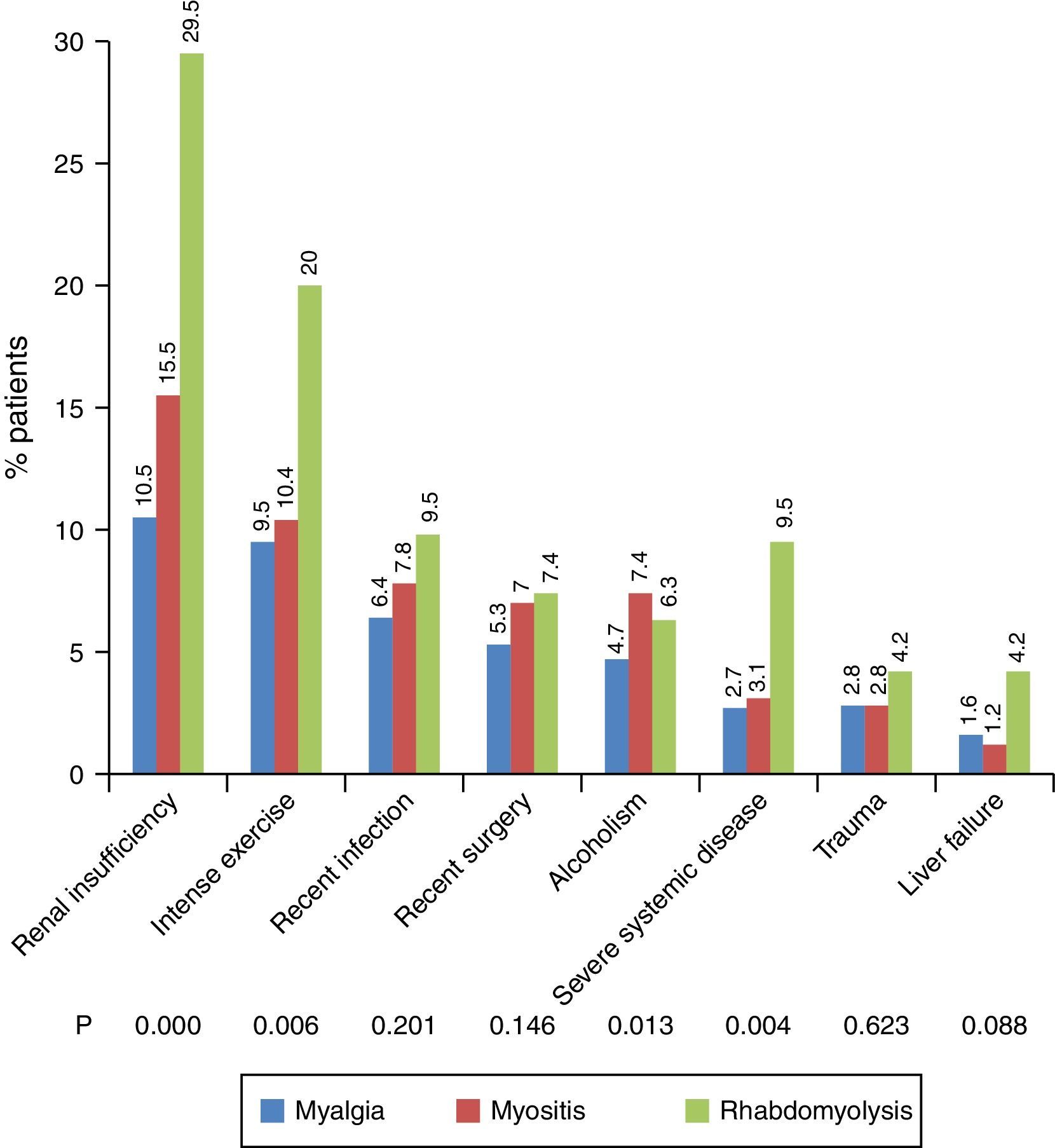

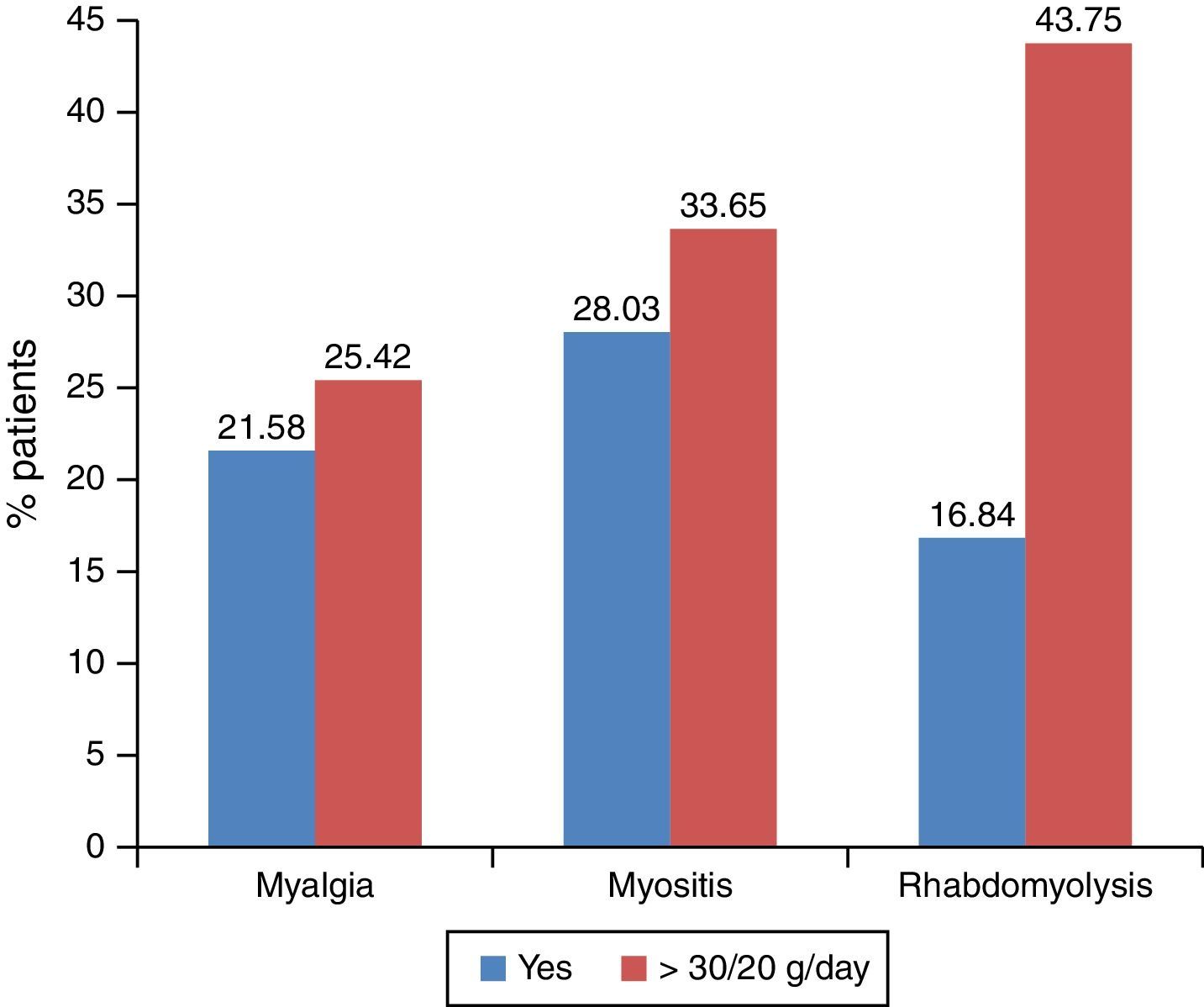

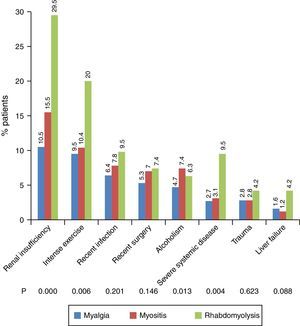

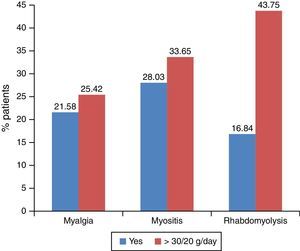

As for the associated comorbidities, 11.9% of patients had kidney failure, 9.9% were performing intense physical exercise, 6.8% had had a recent infection, 5.87% had surgery, 5.3% reported drinking >30g/day of alcohol for men or 20g/day for women, 2.9% had a severe systemic disease, 2.9% had a recent history of trauma, and 1.6% had liver failure. In fact, kidney failure, physical exercise, and alcohol intake showed a significant association with the severity of the myopathy (Fig. 3). In patients with a glomerular filtration rate under 60ml/min, rhabdomyolysis was the most common form of myopathy (36.6%), followed by myositis (21.9% of myopathies in this group), and myalgia (21.2%). Regarding alcohol, drinking >30g/day in men or 20g/day in women was found to be correlated with the onset of rhabdomyolysis (Fig. 4).

Another alteration significantly associated with myopathy severity was abdominal obesity, considered as a waist circumference over 102cm in men and 88cm in women. In patients with abdominal obesity, rhabdomyolysis accounted for 34.7% of all myopathies, 51.4% were myositis, and 45.1% were myalgia (p=0.001, Fisher's test). However, body mass index was not significant associated with the different types of myopathy (p=0.085, Fisher's test).

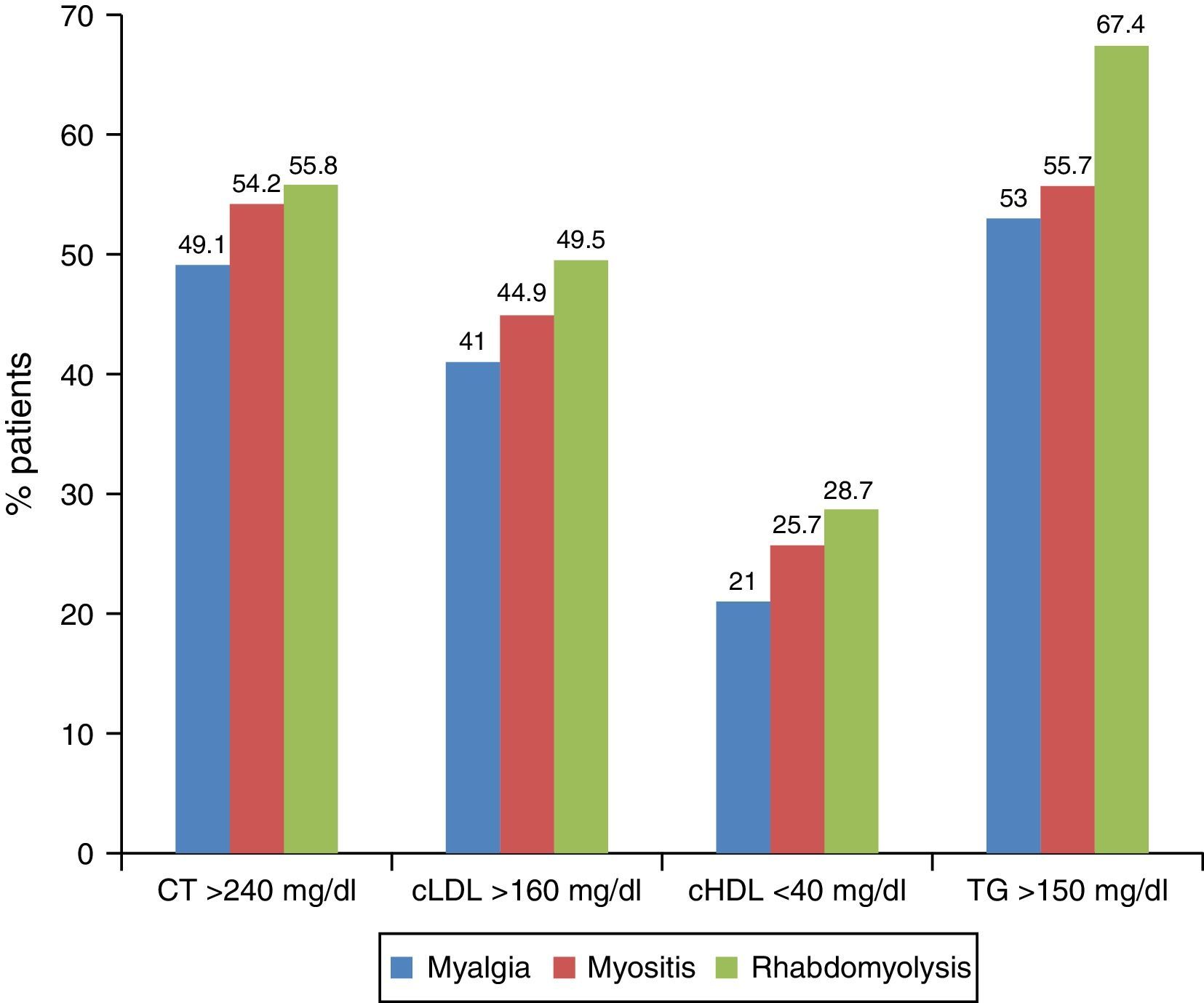

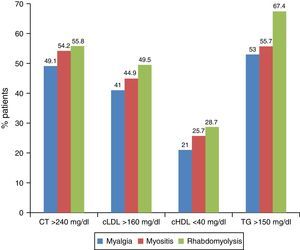

Lastly, at the time of the myopathy diagnosis there was an inverse correlation between cholesterolaemia and myopathy severity. Thus, total cholesterol concentrations >240mg/dL were associated with myalgia in 32.5% of patients, while 31.5% had myositis and 25.3% rhabdomyolysis. The meaning of the statins, and not the decrease in cholesterol, being the key element for myopathy is confirmed by the fact that when assessing the laboratory data prior to the statins (3 months prior) (Fig. 5) a high prevalence of rhabdomyolysis was associated with patients with a higher degree of prior dyslipidaemia, who are exactly those patients who would require a greater therapeutic effort.

DiscussionThe DAMA study found that myalgia, followed by myositis, is the most common statin-associated muscle symptom, which makes it essential to consider the need to educate patients about the warning symptoms, in order to identify and prevent such complications early. Rhabdomyolysis was the most clinically severe form and the least common, as has been described in other studies.2,3,16

Defining and classifying the statin-associated muscle changes (clinical or biochemical) in this study was essentially based on the presence of muscle symptoms and serum CK concentration.15 As symptoms are subjective, it makes it difficult to classify and obtain objective criteria for a precise diagnosis. The most commonly reported symptoms in this study were muscle ace, weakness, and/or muscle cramps. Aches and weakness were usually symmetric and proximal, generally affecting large muscle groups. Muscle weakness usually starts between the first and second month after starting treatment, but it can even occur after several years of treatment.12 Symptoms usually occur more frequently in more active people, or with higher muscle activity,4 as demonstrated in the DAMA study.

Muscle symptoms (aches, weakness, or cramps) with normal CK are terminologically referred to as myalgia; although they can be statin-related, the correlation between the two is not clear and the drug is not always the causal agent. When the muscle symptoms are accompanied by CK elevations between 4 and 10 times the upper limit of normal, they are usually due to reasons other than statins, such as increased muscle activity due to physical exercise, although they may be due to the drug meaning, in any case, an increased risk.9 CK elevation above 10 times the upper limit of normal, along with muscle symptoms of any type, should genuinely be called myopathy or myositis, and it is the most commonly found situation in clinical trials as statin-associated myopathy. In these cases, the muscle ache or weakness is usually generalised and affects the proximal muscle groups. Muscle symptoms with CK elevations above 40 times the limit of normal are usually referred to as rhabdomyolysis, and are accompanied by myoglobinuria and/or kidney failure.

When there are no muscle symptoms, but there is mild-moderate CK elevation (less than 4 times its normal value), the possibility of an incidental CK elevation, either related to the statin, another underlying process, or some environmental factor, will have to be investigated. If in the absence of muscle symptoms, the CK elevation is higher (above 4 times its normal value), the meaning is unclear, although it should be taken into account and monitored to establish regular control. Naturally, should it persist, and even if the association with the statin is not reliable, it will have therapeutic implications as it is considered a potential risk factor.

The risk factors for statin-induced myotoxicity can be classified into those that are patient-related, statin-related, and drug interaction-related. The first group includes advanced age, being female, of Asian origin, body mass index, vigorous exercise, alcohol consumption, drug abuse, untreated hypothyroidism, deteriorated kidney or liver function, bile duct obstruction, intercurrent infection, and the effects of diet as risk factors for statin-induced myotoxicity.16–18 In this study, kidney failure, physical exercise, and alcohol intake demonstrated a significant association with the severity of the myopathy. Similarly, while it remains to be determined whether body mass index is associated with the different types of myopathy, abdominal obesity is significantly correlated with myopathy severity.

Furthermore, it is known that the higher the dose used, the more likely it is that it will cause myotoxic effects.19 Nevertheless, other clinical evidence reveals that the adverse effects of statins in muscles are independent of the reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol,20,21 in line with the findings of this study.

In conclusion, although statins are well-tolerated drugs, adverse effects can limit their use and thus reduce the potential benefit in cardiovascular prevention. Of the adverse effects, clinically or biologically demonstrable muscle changes tend to be the most common. Controlling environmental factors such as intense physical exercise and alcohol intake, as well as abdominal obesity and kidney function should be recommended in patients treated with statins.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Millán J, Pedro-Botet J, Climent E, Millán J, Rius J. Miopatía asociada al uso de estatinas en la práctica clínica. Resultados del estudio DAMA. Clin Invest Arterioscler. 2017;29:7–12.