Renal infarction is a rare disease whose incidence is less than 1%. The symptoms can be abdominal or flank pain, nausea, vomiting, fever or hypertension. The diagnosis is complex, and it is based on symptoms, blood analysis with an elevated level of lactate dehydrogenase and computed tomography angiography. The two major causes of renal infarction are thromboembolism and in situ thrombosis. The treatment depends on an adequate etiological diagnosis.

El infarto renal agudo (IRA) es una patología con frecuencia inferior al 1% y diagnóstico complejo. Puede manifestarse como dolor abdominal o en fosa renal, asociando náuseas, vómitos, fiebre o incluso hipertensión, entre otros. El diagnóstico está basado en una alta sospecha clínica, con elevación de lactato deshidrogenasa (LDH) en los análisis y angio-TC con defecto de perfusión renal parenquimatosa en cuña. En cuanto a la etiología del IRA, podemos distinguir dos grupos etiológicos: tromboembólicos y trombosis in situ. Es importante realizar un adecuado diagnóstico causal para realizar un tratamiento correcto.

Acute renal infarction (ARI) is a rare pathology with a frequency of less than 1%. Classic clinical presentation consists of abdominal or renal fossa pain in up to half of the patients, while other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, or fever, occur in fewer than 20% of affected individuals. ARF is often accompanied by high blood pressure (HBP).1,2 It can be complicated to make a diagnosis, given that the non-specific symptoms may cause the clinician to confuse ARF with other diseases, such as nephrolithiasis or pyelonephritis. As for its aetiology, ARF can be caused by two major mechanisms: thromboembolism and in situ thrombosis.3 What follows is a case report of a patient who presented with a multifactorial renal infarction.

Clinical caseForty-three year old male with a disease history of Poland syndrome affecting his right side, non-smoker, and non-drinker, without any regular treatment. He went to the emergency department for non-radiating pain in the left renal fossa of 48 h of evolution; no fever or other associated symptoms. Physical examination revealed blood pressure (BP) 190/110 mmHg, with no significant differences between both arms and lower extremities.

In complementary testing, the haemogram including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and basic biochemistry (including renal function, transaminases, creatine kinase, and ions) were normal. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 338 U/L (0–248). Baseline coagulation was normal, as were chest and abdominal X-rays. The electrocardiogram revealed sinus rhythm at 74 bpm with narrow QRS, prominent R in V5–V6 without criteria of ventricular hypertrophy.

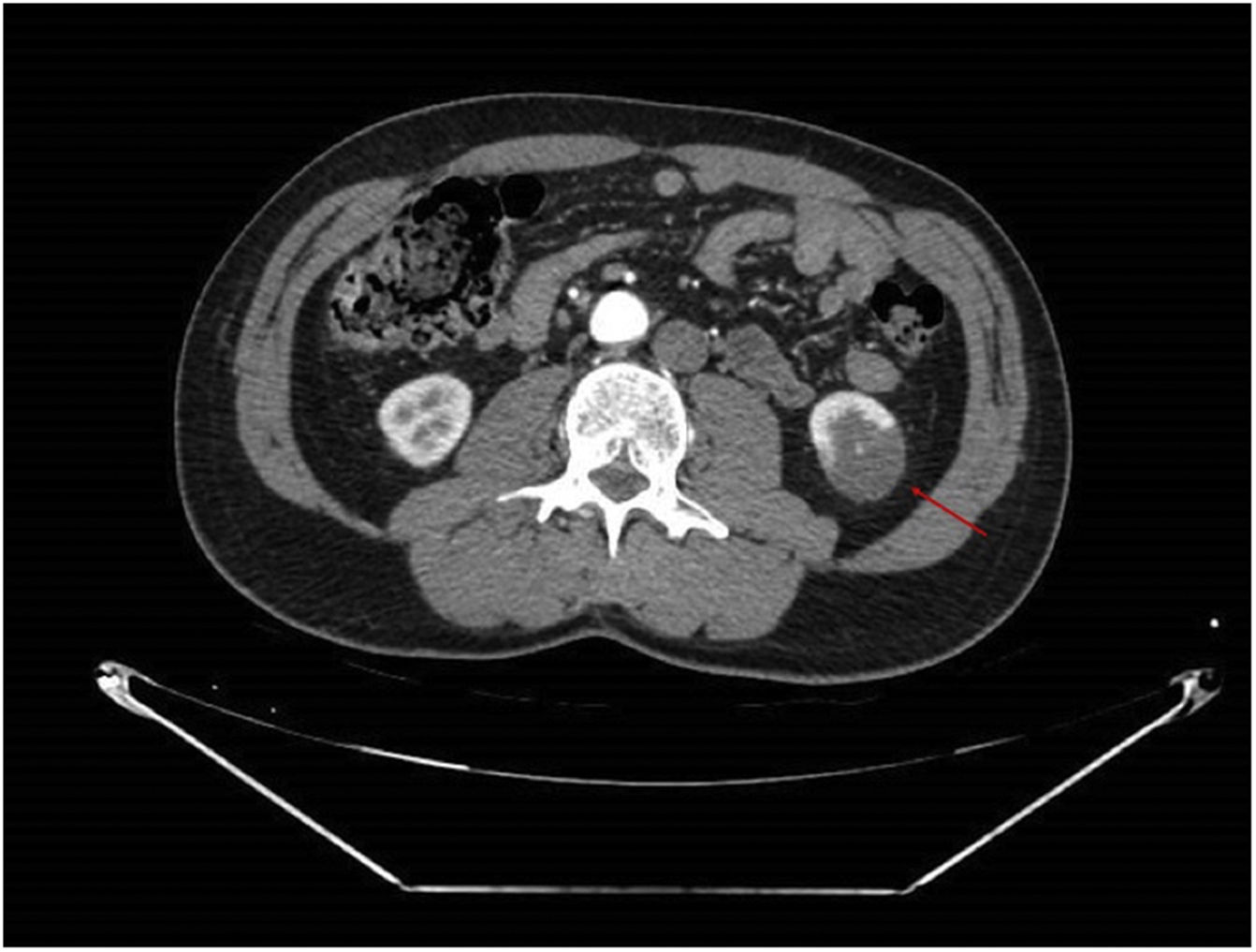

An angioCT of the abdomen and pelvis was performed (Figs. 1 and 2), on which infarction of the left renal lower pole (15% of the renal parenchyma) was evidenced, with a decrease in the calibre of one of the segmental branches of the left renal artery. This finding was suggestive of spontaneous dissection of an inferior branch of the left renal artery, although as small scattered plaques of calcified atheromatosis were present at the level of the abdominal aorta, an emboligenic aetiology or a lesion of the underlying renal artery could not be ruled out.

For this reason, the decision was made to extend the study with a transthoracic echocardiography, which showed no evidence of structural heart disease. In the acute phase, aldosterone was 254 pg/mL (38–150) with normal renin. TSH, ACTH, cortisol, and metanephrines were normal. Lipid profile exhibited total cholesterol 245 mg/dL, HDL-C 49 mg/dL, LDL-C 162 mg/dL, TG 170 mg/dL, apolipoprotein A 118 mg/dL, apolipoprotein B 151 mg/dL, and lipoprotein (a) 163 mg/dL (5.6–33.8). Additionally, the special coagulation study conducted was positive in two independent samples (with more than a 12-week interval between them) for lupus anticoagulant, as well as heterozygous Factor XII c4C>T mutation. The remaining special coagulation studies (anticardiolipin and anti-beta2-glycoprotein I antibodies, homocysteine, factor V Leyden, protein C and S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency) and autoimmunity (ANA, ENAS) were all negative.

With these results, the patient was diagnosed with renal infarction due to probable spontaneous renal artery dissection, without being able to rule out that his procoagulant state, with a confirmed antiphospholipid syndrome, could be involved in the aetiology of this condition. Furthermore, the patient’s high cardiovascular risk due to hyperlipoproteinaemia (a) was considered to have played an important role in the aetiology of the [clinical] presentation.

With respect to treatment, the case was presented in a multidisciplinary session (Internal Medicine, Vascular Surgery, and Interventional Radiology). Given that the patient’s clinical symptoms had been present for more than 48 h and 15% of the parenchyma was affected, the decision was made not to revascularise. The patient was anticoagulated with acenocoumarol indefinitely, in light of his antiphospholipid syndrome, as well as strict control of cardiovascular risk factors. Treatment was initiated with rosuvastatin 20/ezetimine 10 mg daily. After a few hours during which the patient was hypertensive, he did not require antihypertensive treatment.

DiscussionRenal infarction is a rare pathology, with a frequency of less than 1%. It is suspected to be underdiagnosed, given that its clinical presentation is non-specific and can be confused with other more common diseases (nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis, etc.).The finding of renal infarction is often incidental when performing an imaging test.1

The causes of ARI can be divided into two main groups: thromboembolism and in situ thrombosis. The first group includes atrial fibrillation (inasmuch as it is the most frequent aetiology, performing a Holter-ECG may be of interest in these patients), septic thrombi in the context of endocarditis, or thrombi formed as a result of the rupture of an atheroma plaque of the suprarenal aorta. Less common are direct thromboses in the renal artery. They can arise from spontaneous dissection, trauma, fibromuscular dysplasia, polyarteritis nodosa, or Marfan syndrome. Less than 10% of all ARI are caused by hypercoagulable states. In up to one third of the cases, the cause of renal infarction is never determined.2,3 A higher incidence of renal infarct dissection in Poland syndrome has not been reported.

The diagnosis of ARI is primarily based on a high degree of clinical suspicion, supported by elevated LDH concentrations in the analysis and confirmed by angio-CT, where a wedge-shaped parenchymal perfusion defect is typically observed.4

In our case, there were several possible explanations for ARI. The angioCT lesion initially suggested a spontaneous dissection of the segmental branch of the left renal artery. In addition, the patient had an antiphospholipid syndrome and atheroma plaques in the aorta with very high lipoprotein (a) values, with the high risk of cardiovascular disease this entailed, making it impossible to be sure that the AKI was attributable to any one of these causes alone; the three factors therefore had to be treated individually.

As for ARI treatment, the first step should be to assess the possiblility of reperfusion of the artery.5,6 The patients seen to benefit most are those with an evolution time of less than 24 h; those having an ARI of more than 24 h and with new-onset AHT or worsening of the usual figures, renal failure, haematuria, or fever, and those patients in whom ARI is caused by a dissection of the renal artery. Individuals with atrophic kidneys do not benefit from treatment with arterial reperfusion. In all patients, the need for anticoagulation should be evaluated, as well as strict control of cardiovascular risk factors.2 In many cases, patients can develop hypertension during the first week, due to renin release.

In conclusion, ARI is difficult to diagnose and requires a complex aetiological study for adequate treatment.

FundingThe authors state that they have not received any funding for this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: González-Bustos P, Roa-Chamorro R, Jaén-Águila F. ¿Quién disparó primero? Infarto renal de tres posibles causas. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2021;33:203–205.