Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are considered the leading cause of death globally. This study describes the demographic characteristics, treatment patterns, self-reported compliance and persistence, and to explore variables related to non-adherence of patients enrolled in the cardiovascular patient support program (PSP) for evolocumab treatment in Colombia.

MethodsThis retrospective observational of the data registry of patients who entered the evolocumab PSP program.

ResultsThe analysis included 930 patients enrolled in the PSP (2017–2021). Mean age was 65.1 (SD ± 13.1) and49.1% patients were female. The mean compliance rate to evolocumab treatment was 70.5% (SD ± 21.8). A total of 367 patients (40.5%) reported compliance higher than 80%. Persistence analysis included 739 patients (81.5%) where 87.8% of these patients were considered persistent to treatment. A total of 871 patients (93.7%) reported the occurrence of at least one adverse event during the follow-up period (mostly non-serious).

ConclusionThis is the first real-life study describing patient characteristics, compliance and continuity of treatment for dyslipidemia in a patient support program in Colombia. The overall adherence found was higher than 70%; similar to findings reported in other real-life studies with iPCSK9. However, the reasons for low compliance were different, highlighting the high number of administrative and medical reasons for suspension or abandonment of treatment with evolocumab.

Las enfermedades cardiovasculares (ECV) son la principal causa de muerte a nivel mundial. El objetivo es describir las características demográficas, los patrones de tratamiento, cumplimiento terapéutico y continuidad del tratamiento; y explorar las variables relacionadas con la falta de adherencia de los pacientes inscritos en programa de apoyo al paciente (PSP, por sus siglas en inglés) cardiovascular para al tratamiento con evolocumab en Colombia.

MétodosEstudio observacional-retrospectivo del registro de datos de los pacientes que ingresaron al programa PSP de evolocumab.

ResultadosEl análisis incluyó a 930 pacientes inscritos en el PSP (2017–2021). La edad media fue de 65.1 años (DE ± 1.1) y el 49.1% eran mujeres. La tasa media de cumplimiento del tratamiento con evolocumab fue del 70.5% (DE ± 21.8). Un total de 367 pacientes (40.5%) reportaron una tasa de cumplimiento superior al 80%. El análisis de continuidad incluyó a 739 pacientes (81.5%); el 87.8% de estos pacientes fueron considerados persistentes al tratamiento. Un total de 871 pacientes (93.7%) reportaron al menos un evento adverso durante el período de seguimiento (en su mayoría no serios).

ConclusiónPrimer estudio de la vida real sobre el tratamiento para la dislipidemia en un programa de apoyo a pacientes en Colombia. La adherencia encontrada fue superior al 70%; similar a los hallazgos de otros estudios de vida real. Entre las causas del bajo cumplimiento se destacan las barreras administrativas y médicas para la suspensión o abandono del tratamiento con evolocumab.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are considered the leading cause of death globally.1,2 In 2019, the World Health Organization estimated 17.9 million deaths from CVD, representing 32% of all deaths worldwide for that year.1 The development of CVD is primarily related to risk factors, which can be modified through the implementation of therapeutic lifestyle changes and complementary drug therapy.3

Statins are the mainstay of lipid-lowering therapy and are therefore the treatment of first choice due to their proven effectiveness in reducing the risk for vascular events primarily by lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). However, to achieve the proposed therapeutic goals, it is often necessary to add other treatments.3 In general, drugs such as ezetimibe and fibrates can be combined with statins to achieve a reduction in different lipid fractions; however, in many cases this is insufficient, requiring inhibitors of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin convertase type 9 (iPCSK9), which are usually used in patients who need to achieve low LDL-C levels due to their cardiovascular (CV) risk, and in patients who permanently have very high LDL-C levels or who are intolerant to statins.3

Guidelines on treatment goals and targets for CVD prevention in patients at high cardiovascular risk recommend a treatment regimen that achieves an LDL-C reduction of ≥50% from baseline and an LDL-C target between <1.4 mmol/L (<55 mg/dL) and <1.8 mmol/L (<70 mg/dL).4,5

Repatha® (evolocumab) is a fully human monoclonal immunoglobulin G2 antibody that targets PCSK9. Evolocumab leads to a reduction in circulating PCSK9, LDL-C, total cholesterol, apolipoprotein B, and non-HDL cholesterol, with an increase in HDL-C and apolipoprotein I1 in patients with primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia.3 In Colombia, evolocumab is indicated as an adjuvant to diet, in combination with statins, or with other treatments in patients with statin intolerance or for whom statins are not a clinically appropriate treatment, to reduce LDL cholesterol levels in the management of primary hyperlipidaemia, mixed dyslipidaemia, and as prevention of cardiovascular events at a dose of 140 mg every 2 weeks and the management of familial hypercholesterolaemia at a dose of 420 mg monthly.6

Therapeutic adherence is the most important factor in achieving the therapeutic target of lipid-lowering treatment.7 The reasons for poor adherence may include the asymptomatic nature of early CVD and the many tablets associated with specific treatments.8 Patients with a history of hypertension, heart failure, and myocardial infarction who have shown poor adherence to their treatment (primarily statin treatments) have been associated with problems such as poor blood pressure control, hospitalisation, and increased utilisation of healthcare resources.8 In addition, around 50% of CVD patients have been found to have poor adherence to prescribed medication.7

In real-life scenarios, the impact of non-adherence on clinical outcomes has been described in the literature. Studies in Europe have consistently shown that patients with low adherence levels are less likely to achieve therapeutic targets of LDL-C reduction. Furthermore, low adherence in these patients has been associated with higher frequencies of major adverse cardiac events.10 Interventions have been developed to improve adherence to lipid-lowering therapies: Deichmann et al. found in their systematic review of 27 clinical trials that intensified care interventions showed a significant increase in adherence rates compared to routine care.11 Local research is therefore needed to identify strategies to improve adherence and to identify barriers that affect treatment persistence, and which would enable achievement of the demonstrated clinical benefit.

Studies in Latin America show that low adherence to antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy correlates with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and CVD.12 Studies in Colombia describe the association between factors such as demographic characteristics, treatment patterns, and patient adherence.9,10 In a study of 347 patients with hypertension, it was found that factors associated with low adherence to treatment included the type of health insurance (subsidised scheme), low educational level, and lack of information about the benefits of treatment.13

On the other hand, a study of 293 patients enrolled in chronic disease support programmes (including hypertension) showed that the risk of non-adherence is associated with deficiencies in clinical practice guidelines, lack of guidance in organising drug dosing regimens, lack of written treatment recommendations, and lack of adequate introspection about their health status, leading to a low perception of CVD risk.14 In contrast, this study showed that factors that support networks, socio-economic status, allowing basic needs to be met, and organised health systems and teams were factors that improved adherence.14

The present study aims to describe the demographic characteristics of patients enrolled on a cardiovascular patient support programme (PSP) for treatment with evolocumab, and to describe the patterns of treatment, therapeutic compliance, and persistence reported by patients or their caregivers/family members and to explore variables related to low adherence.

Materials and methodsA retrospective observational study of registry data of patients entering the PSP for evolocumab in Colombia from its inception in 2017–2021.

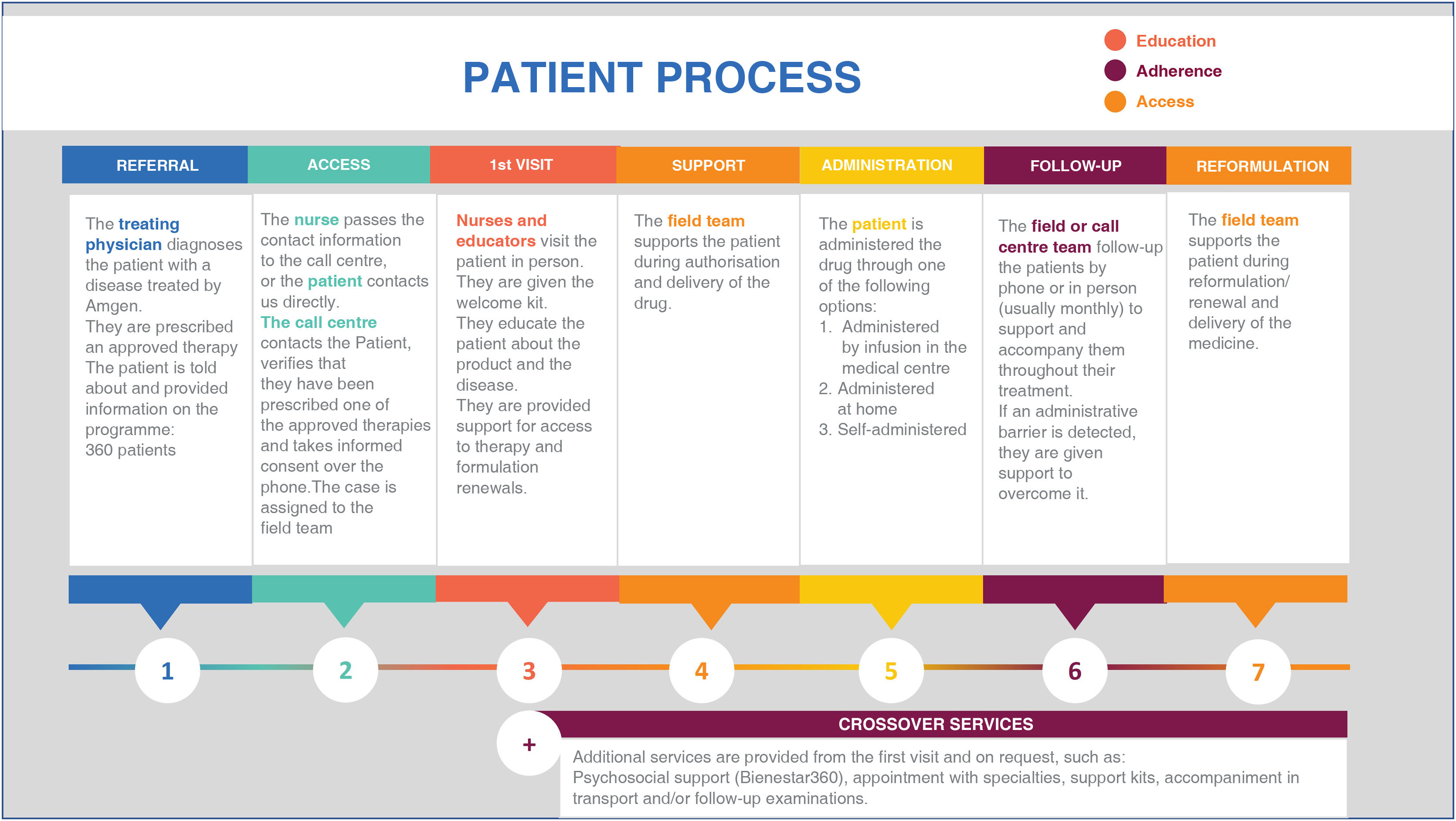

The PSP for evolocumab is an active patient support programme, of the private sector, funded by AMGEN and implemented by an external provider. The main objective of the programme is to promote understanding of the health condition and the comprehensive management of treatment; therefore, activities include disease education, comprehensive counselling on the drug and healthy lifestyles, reporting, and monitoring of adherence to the drug, supporting the processes of authorisation, renewal, or reformulation of the drug, and reinforcing the importance of following the recommendations of the treating physician. Fig. 1 presents a detailed description of the phases and activities of the PSP.

Once patients are given a prescription for evolocumab, their physician may refer them to the PSP and then the programme's call centres contact patients to initiate support and follow-up. The are followed-up by trained nurses at least once a month. In order to be included in the PSP, the evolocumab prescription must be verified and the patient's informed consent is required. The PSP does not provide the patients any financial support.

Demographic characteristics (sex, age, region, type of insurance), treatment patterns (dosage, dosing regimen), and compliance and persistence were assessed, which were defined as variables related to treatment adherence. The frequency of adverse events was also assessed using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Exploratively, potential associations between demographic characteristics and the results of treatment compliance and persistence were evaluated.

Demographic characteristics and treatment patterns (including self-reported therapeutic compliance and persistence) were obtained from monthly telephone calls from inclusion in to exiting the PSP. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Caribbean Foundation for Biomedical Research under the CEI-BIOS 20210190APR01 act of 21 December 2021.

Statistical analysisContinuous data (age, time on treatment, doses taken) were summarised as means or medians, with standard deviation or interquartile range, depending on the type of distribution. Categorical data (sex, geographic region, affiliation, drug regimen) were summarised as frequencies and percentages.

Exploratory outcomes included potential associations between demographic variables and self-reported adherence and continuation outcomes. A t-test for differences in means and a one-way ANOVA test (with Bonferroni adjustment) were performed to assess possible differences between subgroups for the adherence relationship.

Considering that patients with shorter follow-up time might overestimate treatment compliance and persistence, patients were grouped according to their length of time on the programme, which allowed analysis over periods of 6 months.

Patient-reported therapeutic compliance and persistenceCompliance was calculated from the estimated compliance rate15:

A patient was considered fully compliant if the rate of therapeutic adherence was ≥80%.7 Persistence was defined as the average time from treatment initiation to definitive discontinuation and was calculated from the number of months patients continued evolocumab use according to the medical treatment plan.15 Evolocumab persistence was considered adequate if patients remained on treatment without definitively discontinuing treatment prior to the treating physician's indications. Patients on treatment at the end of the follow-up period were censored, i.e., for those who were still on evolocumab at the date of database closure, 30 September 2021 was assigned as the end date of treatment, so that the number of total doses could be estimated.

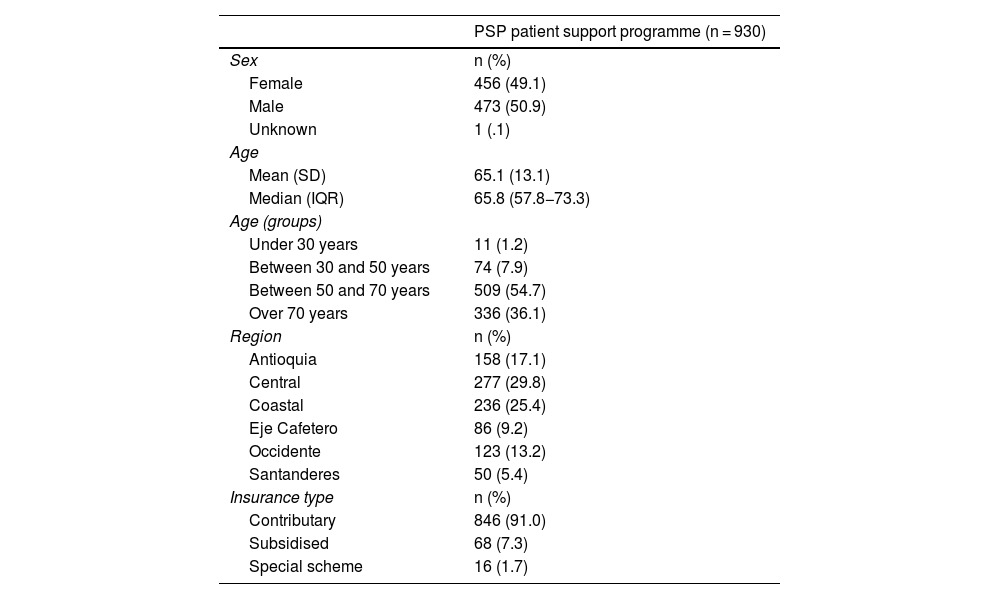

ResultsThe analysis included a total of 930 patients enrolled on the PSP from its start in 2017 until the data cutoff on 30 September 2021. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the population included in the analysis.

Demographic characteristics of the patients.

| PSP patient support programme (n = 930) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | n (%) |

| Female | 456 (49.1) |

| Male | 473 (50.9) |

| Unknown | 1 (.1) |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 65.1 (13.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 65.8 (57.8−73.3) |

| Age (groups) | |

| Under 30 years | 11 (1.2) |

| Between 30 and 50 years | 74 (7.9) |

| Between 50 and 70 years | 509 (54.7) |

| Over 70 years | 336 (36.1) |

| Region | n (%) |

| Antioquia | 158 (17.1) |

| Central | 277 (29.8) |

| Coastal | 236 (25.4) |

| Eje Cafetero | 86 (9.2) |

| Occidente | 123 (13.2) |

| Santanderes | 50 (5.4) |

| Insurance type | n (%) |

| Contributary | 846 (91.0) |

| Subsidised | 68 (7.3) |

| Special scheme | 16 (1.7) |

IQR: Interquartile Range.

The primary outcome included the demographic characteristics of patients enrolled on the PSP. There was a balanced gender distribution among the participants (49.1% female). The mean age was 65.1 (SD±13.1), most of the patients were aged 50−70 years (54.7%) and a smaller proportion were aged over 70 years (36.1%). Most participants belonged to the central area of Colombia (29.8%), followed by participants from the coastal region (25.4%). Finally, most of the patients were enrolled on the contributory health scheme (91.0%).

A total of 919 patients had data available for outcomes related to treatment patterns (98.8%). In relation to treatment frequency, most of the patients had a fortnightly medication regimen (98.5%), 9 patients a monthly regimen (0.9%), other regimens were reported for 3 patients: 2 with a 20-day regimen (.2%), and one patient a regimen of every 21 days (.1%).

The average time between drug delivery and administration date was 1.2 days (SD±4.4), with a minimum of 0 days between delivery and administration and a maximum of 110 days between the two dates. Patients who completely discontinued the programme were considered inactive; criteria for inactivity included a change or definitive discontinuation of treatment by medical judgement, patient decision, loss to follow-up greater than 2 months, occurrence of adverse events leading to treatment abandonment, or patient death. At the end of the follow-up time 219 patients were inactive from the programme (23.5%); among these patients, the mean time from enrolment on the programme and the date of inactivation was 11.8 months (SD±9.8).

Self-reported compliance and persistence with evolocumabA total of 906 (97.4%) patients were included in the self-reported treatment compliance analysis. The reasons for excluding the remaining 24 patients are presented in Supplementary Table 1 in the Appendix.

From entering the PSP to discontinuation or data cutoff, the mean duration of patients on the programme was 18 months (SD ± 12.3), in which the mean number of doses received per patient was 35.9 (SD ± 24.7).

Compliance was assessed from enrolment of the patient on the PSP. The average compliance rate with evolocumab treatment was 70.5% (SD ± 21.8). A total of 367 patients (40.5%) had compliance above 80%, which corresponds to the expected compliance for this type of therapy.

Persistence was assessed as the time (months) from the start of treatment to its definitive discontinuation for reasons other than the treating physician's decision. In other words, patients who discontinued the drug according to medical criteria were not included in the persistence analysis. Of the 906 patients included in the compliance analysis, 257 (28.3%) reported complete treatment discontinuation (inactivation) and 64.9% (n = 167) discontinued treatment due to medical decisions.

Due to the above, the persistence analysis included 739 patients (81.5%). At the end of follow-up, 87.8% of these patients (n = 649) continued to be treated with evolocumab; ergo, 87.8% were considered treatment persistent. The median time from treatment initiation to discontinuation was 18.0 months (SD ± 11.9).

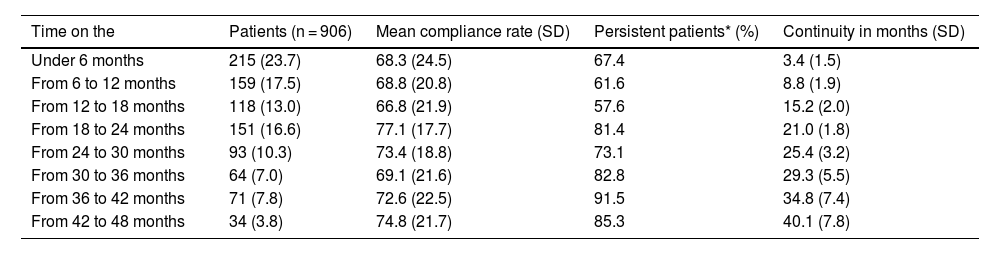

Table 2 presents compliance and persistence results according to the length of time the patients had been on the PSP. The highest compliance rates (>70%) are found in subgroups of patients who have been on the programme for approximately 2 years and up to 3 years: this shows that the longer patients stay on the programme, the higher the treatment persistence.

Compliance and persistence rate according to time on PSP.

| Time on the | Patients (n = 906) | Mean compliance rate (SD) | Persistent patients* (%) | Continuity in months (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 6 months | 215 (23.7) | 68.3 (24.5) | 67.4 | 3.4 (1.5) |

| From 6 to 12 months | 159 (17.5) | 68.8 (20.8) | 61.6 | 8.8 (1.9) |

| From 12 to 18 months | 118 (13.0) | 66.8 (21.9) | 57.6 | 15.2 (2.0) |

| From 18 to 24 months | 151 (16.6) | 77.1 (17.7) | 81.4 | 21.0 (1.8) |

| From 24 to 30 months | 93 (10.3) | 73.4 (18.8) | 73.1 | 25.4 (3.2) |

| From 30 to 36 months | 64 (7.0) | 69.1 (21.6) | 82.8 | 29.3 (5.5) |

| From 36 to 42 months | 71 (7.8) | 72.6 (22.5) | 91.5 | 34.8 (7.4) |

| From 42 to 48 months | 34 (3.8) | 74.8 (21.7) | 85.3 | 40.1 (7.8) |

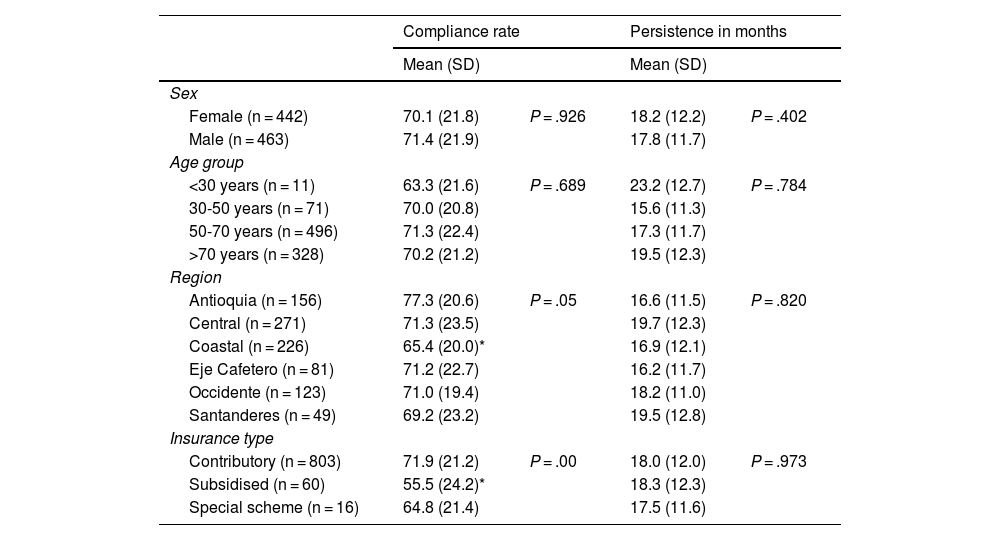

Exploratory outcomes included the association between demographic variables with treatment compliance and persistence. Table 3 presents the results of self-reported compliance and persistence according to sex, age, region, and type of health insurance.

Self-reported compliance and persistence among subgroups.

| Compliance rate | Persistence in months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female (n = 442) | 70.1 (21.8) | P = .926 | 18.2 (12.2) | P = .402 |

| Male (n = 463) | 71.4 (21.9) | 17.8 (11.7) | ||

| Age group | ||||

| <30 years (n = 11) | 63.3 (21.6) | P = .689 | 23.2 (12.7) | P = .784 |

| 30-50 years (n = 71) | 70.0 (20.8) | 15.6 (11.3) | ||

| 50-70 years (n = 496) | 71.3 (22.4) | 17.3 (11.7) | ||

| >70 years (n = 328) | 70.2 (21.2) | 19.5 (12.3) | ||

| Region | ||||

| Antioquia (n = 156) | 77.3 (20.6) | P = .05 | 16.6 (11.5) | P = .820 |

| Central (n = 271) | 71.3 (23.5) | 19.7 (12.3) | ||

| Coastal (n = 226) | 65.4 (20.0)* | 16.9 (12.1) | ||

| Eje Cafetero (n = 81) | 71.2 (22.7) | 16.2 (11.7) | ||

| Occidente (n = 123) | 71.0 (19.4) | 18.2 (11.0) | ||

| Santanderes (n = 49) | 69.2 (23.2) | 19.5 (12.8) | ||

| Insurance type | ||||

| Contributory (n = 803) | 71.9 (21.2) | P = .00 | 18.0 (12.0) | P = .973 |

| Subsidised (n = 60) | 55.5 (24.2)* | 18.3 (12.3) | ||

| Special scheme (n = 16) | 64.8 (21.4) | 17.5 (11.6) | ||

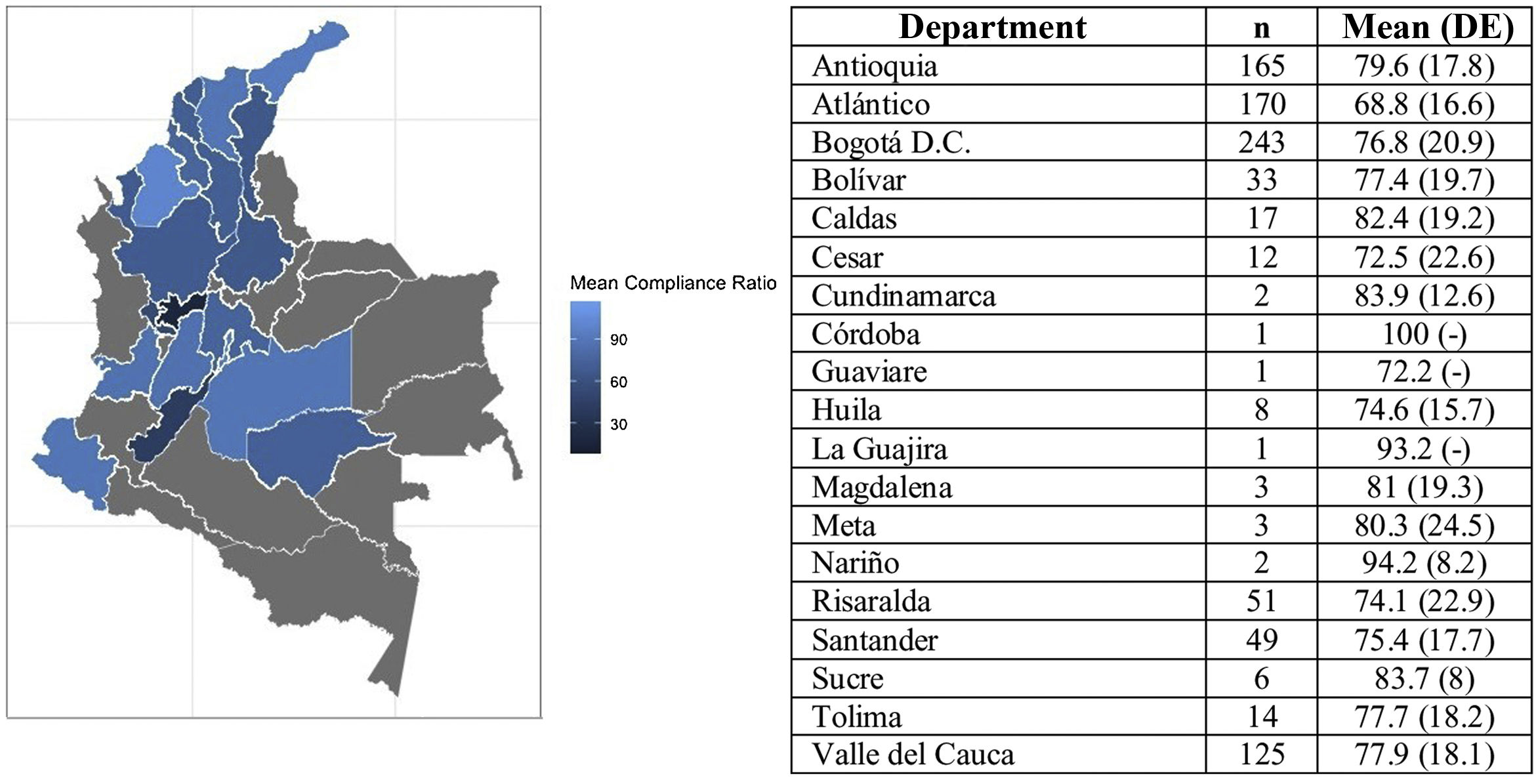

The results showed that between the sex and age subgroups there were no statistically significant differences in compliance. In contrast, for the distribution by region, the compliance rate of patients from the coastal region was identified at 11.8% lower than the rate reported by patients from Antioquia and 5.9% lower than the rate reported by patients from the central region. Fig. 2 presents the average compliance rate according to Colombia’s departments. The majority of patients on the PSP are located in the departments of Antioquia, Atlántico, and Bogotá D.C., where the compliance rate was reported at between 68.8% and 79.6%. Other departments, such as Risaralda, Santander, and Bolívar, where the number of patients is lower, reported compliance rates above 70%.

Finally, in terms of type of insurance, a statistically significant difference was identified in the compliance rate between patients in the contributory scheme and those in the subsidised scheme, the latter with a 16.4% lower compliance rate, a population that corresponds to only 7.3% of the sample.

In terms of persistence, no statistically significant difference in time from treatment initiation to discontinuation was identified in any of the subgroups.

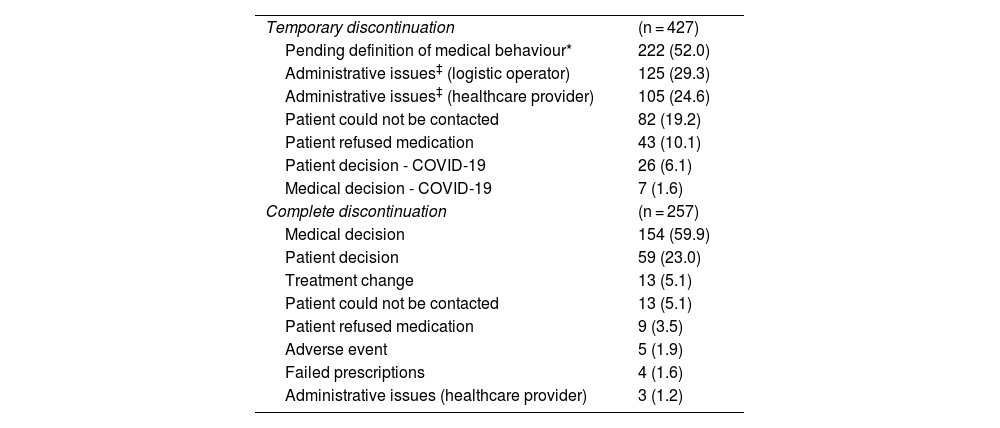

Reasons for discontinuing treatmentTable 4 presents the reasons for temporary and complete treatment discontinuation. Among the 906 patients with compliance data, 47.1% of the participants (n = 427) reported temporary discontinuation of treatment at some point during the follow-up period (2017–2021). Among these, 1.6% (n = 7) were associated with medical decisions and 47.7% (n = 204) were associated with access issues. Of the participants, 28.3% (n = 257) reported abandoning treatment in the follow-up period. Of these, 65% (n = 167) of discontinuations were due to medical decisions, despite being a chronic treatment, whereas 1% (n = 3) were related to access problems.

Reasons for discontinuing treatment.

| Temporary discontinuation | (n = 427) |

| Pending definition of medical behaviour* | 222 (52.0) |

| Administrative issues‡ (logistic operator) | 125 (29.3) |

| Administrative issues‡ (healthcare provider) | 105 (24.6) |

| Patient could not be contacted | 82 (19.2) |

| Patient refused medication | 43 (10.1) |

| Patient decision - COVID-19 | 26 (6.1) |

| Medical decision - COVID-19 | 7 (1.6) |

| Complete discontinuation | (n = 257) |

| Medical decision | 154 (59.9) |

| Patient decision | 59 (23.0) |

| Treatment change | 13 (5.1) |

| Patient could not be contacted | 13 (5.1) |

| Patient refused medication | 9 (3.5) |

| Adverse event | 5 (1.9) |

| Failed prescriptions | 4 (1.6) |

| Administrative issues (healthcare provider) | 3 (1.2) |

Patients may report multiple reasons for discontinuation; therefore, the reasons may amount to more than 100%.

†The patient’s prescription was reviewed and was out of date or the patient should never have been given the prescription.

Supplementary Table 2 in the Appendix presents the reasons for temporary and complete treatment discontinuation according to the patients' level of therapeutic compliance (compliance <80% or ≥80%). Stratified analysis of the reasons for discontinuation showed differences particularly in patients with an adequate therapeutic compliance rate (≥80%), where temporary discontinuation was less associated with medical decision (31.9%) and more associated with temporary loss of contact (28.7%), without this affecting a compliance rate of above 80%.

Safety outcomesAdverse events were defined as “any unexpected and untoward occurrence in a patient administered a pharmaceutical product that does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment”.12 Adverse events were classified following the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5.0. A total of 871 patients (93.7%) reported the occurrence of at least one adverse event during the follow-up period.

Appendix B Supplementary Table 3 in the Annex presents the 10 most frequently reported adverse events, which occurred in at least 3% of the analysed population. The reporting of adverse events was not exclusive of treatment-emergent events, therefore no causal relationship between evolocumab treatment and the occurrence of these events is indicated, only events reported by patients during the follow-up period are recorded. Covid-19 (7.6%), headache (7.5%), and dizziness (6.9%) were the most frequently reported adverse events.

Serious adverse events were defined as any undesirable experience associated with the use of a medical product in a patient that could result in death, life-threatening situation, hospitalisation (initial or prolonged), disability, permanent damage, congenital anomaly, or disability.16 Appendix B Supplementary Table 3 of the Annex also presents the 10 most frequently reported serious adverse events. In total, 313 patients reported at least one serious adverse event [33.6%). The reporting of serious adverse events was also not exclusive to treatment-related events. The most frequently reported serious adverse event was Covid-19 [4.8%); other frequently reported serious adverse events were myocardial infarction (2.1%) and unstable angina (1.4%). Three were hospitalised (.3%) and 5 patients died (.5%) during the study; the reason for death was not reported by the patients' relatives.

DiscussionOngoing treatment for dyslipidaemia is essential to prevent CVD; however, despite the proven efficacy of lipid-lowering therapies in reducing cardiovascular risk, low adherence to treatment compromises their benefit.17 Research on adherence to CVD preventive therapy has shown that approximately 50% of patients have low adherence to prescribed medication.7

Low adherence to lipid-lowering therapy is mostly reflected in real-life scenarios, associated with an increased risk of hospitalisations and mortality, particularly in high-risk patients.17 Research comparing clinical outcomes according to adherence has found worse clinical outcomes in patients with low treatment adherence. Mazhar et al. in an observational study of 20,490 patients with a history of myocardial infarction or treated by coronary revascularisation found that patients with lower adherence to lipid-lowering therapy had a higher risk of major cardiac events (HR: .91; 95% CI: .89–.94)10. Likewise, the impact of non-adherence on the achievement of therapeutic targets has been reported: Guglielmi et al. found in a retrospective analysis of 18,423 patients at very high cardiovascular risk, newly treated with statins, ezetimibe, or their combination, that high adherence increased the likelihood of reaching the LDL-C therapeutic target more than 2-fold at 6-month follow-up (OR: 2.74; 95% CI: 2.27–3.31).9

The superiority of PCSK9 inhibitors related to the availability of easy-to-use and effective devices for self-administration has been associated with improvements in adherence to lipid-lowering therapy.17 In fact, studies of self-administration mechanisms for evolocumab in the home have shown that it is safe and effective to use with proper training and instructions from a healthcare provider: successful self-administration of evolocumab in the home setting has been achieved in approximately 95% of attempts.18

In this real-life study, which included more than 900 patients treated with evolocumab in Colombia enrolled on a PSP, treatment compliance was shown to be over 70% in times of the pandemic. It was also found that 87.8% remained active on treatment during the follow-up period despite periods of lockdown. These results are consistent with studies in real-life settings, which show high adherence to treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors, particularly evolocumab, with compliance rates of up to 79%,19 or even higher cumulative persistence, as is the case in the SAFEHEART study conducted in Spain with patients treated with PCSK9 inhibitors between 2016 and 2021 and which found a 5-year cumulative persistence of 96.1%.20

In contrast, the Zerbini study also conducted in Colombia with 114 patients receiving evolocumab to treat hypercholesterolaemia reported persistence rates of 72%,21 indicating that participation in the PSP programme may favour persistence. However, a comparative study between patients included and not included in the PSP would be required to confirm this.

Despite identifying a compliance rate of over 70% and a persistence rate of 87.8%, the adherence results of the present study are lower than those reported in other countries, including Spain,20 which could be related to our findings on the existence of local barriers affecting adherence to treatment.

Of the patients who permanently discontinued treatment, 65% of cases were related to medical decisions on a therapy that requires persistence to achieve benefits in terms of risk reduction, despite the fact that evolocumab has consistently demonstrated clinical benefit in reducing LDL-C with reductions of 74.1% compared with placebo over the long term at follow-ups of up to 8.4 years,22 or in real-life settings, with reductions of 57.6% within the first 3 months of treatment.23 As a finding of the present study, there is evidence for the opportunity for medical education actions aimed at raising awareness of the importance of persistence with chronic therapies, as in the case of evolocumab in patients at high and very high cardiovascular risk: the impact of these therapies can serve as a future project to evaluate their effect.

Regarding temporary discontinuation, the present study showed that almost half the patients reported temporary discontinuation of treatment at some point during the follow-up period, with 47.7% due to access problems. Administrative issues have been reported in the literature as one of the main barriers to treatment with evolocumab, due to difficulties in obtaining the drug, primarily due to coverage problems.17

The reasons identified that limit treatment persistence are consistent with other studies conducted in Colombia, in which patients treated for hypertension have reported administrative reasons (such as type of health insurance) as factors related to low adherence to treatment.13

The Colombian health system is a solidarity-based system, comprising 2 schemes: contributory and subsidised. Citizens who are financially able, i.e., employees or self-employed workers, must make compulsory contributions to the health system, which is how it is financed. Citizens who do not have the financial means to make monthly contributions are covered by the contributions made by members of the contributory scheme and by contributions from the State. The military forces, the national police, and teachers, among others, belong to a special scheme.

In our study, patients under the subsidised scheme showed 16.4% lower compliance than patients in the contributory scheme. Historically, the amount that the State provides to health risk management entities in Colombia is lower for the population in the subsidised scheme than in the contributory scheme. Although this amount has been equalising in recent years, this inequity in resources during the period under analysis may partially explain the lower adherence, as differential financing may have an impact on timely access to health services. On this point, previous local work has analysed the reasons why membership of a health scheme in Colombia may impact health outcomes and has found that the subsidised scheme has higher barriers to access, including differential care (organisational barrier), longer waiting times for appointments in general and specialised medicine, and lower utilisation of preventive services.24

It is also important to mention that, during the present study, the dispensing of evolocumab required additional authorisation that had to be requested by the physician (MIPRES), which could affect treatment persistence, a factor that could impact the adherence of the entire population studied, regardless of healthcare insurance scheme. Currently, the dispensing of evolocumab no longer requires authorisation through the MIPRES system, which could improve the timeliness of treatment. In addition, Colombia has a drug price regulation process, including evolocumab, which ensures access in all regions of the country.25

Access issues require an awareness-raising strategy to reduce barriers that could influence the clinical benefit of evolocumab use, which should be equitable regardless of the type of patient insurance or authorisation processes. Also, the high number of discontinuations due to medical decisions needs to be reconsidered, despite scientific evidence supporting the benefit of evolocumab in preventing CVD in high- and very high-risk patients.

An additional subgroup that showed a low level of adherence was patients from the coastal region compared to other areas of the country. In contrast, no statistically significant differences in compliance or persistence were identified between the different age groups. One possible explanation is the lack of doctors and medical specialists in rural areas of the country, which may have impacted the definition of medical behaviours necessary for treatment persistence or discontinuation.26 Further research is needed to explore the reasons for the subgroup results found in the analysis.

Furthermore, a possible variable related to administrative issues in receiving the medicine could be the health crisis generated by the Covid-19 pandemic, which drastically affected primary healthcare and pharmacy services during the analysis period of the present study. Particularly in chronic diseases, evidence suggests that the Covid-19 crisis was reflected in service closures, lack of follow-up, or behavioural changes that prevented medication reorders, which could lead to a decrease in adherence to chronic treatments due to factors not related to medication.27,28

In terms of safety outcomes, the most frequently reported adverse events (>3%) were consistent with the reported safety profile of evolocumab,29 events such as influenza, headache, and dizziness being among the most frequent. However, rates were moderately different in our study, which showed a higher frequency of headache (7.5%) and dizziness (6.9%) compared to the Food and Drug Administration report for evolocumab (4.0 and 3.7%). The safety outcomes are consistent with the FOURIER-OLE clinical study, which reported a favourable safety profile for evolocumab, with up to 20% reductions in the risk of major cardiovascular events compared to placebo.30 However, it is important to mention that adverse event data reported on the PSP database do not necessarily correspond to those related to treatment, and therefore situations such as Covid-19 may have exacerbated the reporting frequency of some symptoms.

This is an observational study on adherence using real-world data. Real-world studies have limitations due to their design and methodology. In addition, since adherence to treatment during the follow-up period is mostly dependent on variables not controlled in observational studies (e.g., changes in the treatment plan), temporary or permanent treatment discontinuation was strongly affected by the decisions of the treating physician.

Another limitation to compliance and persistence outcomes relates to the self-reporting of these variables, as they are subjective measures of adherence that rely on the patient's or caregiver's memory to recall the number of doses taken, which may lead to potential errors in estimating the results. However, given that the evolocumab administration regimen is monthly or every 2 weeks and the frequency of follow-up was monthly, the potential impact of the use of subjective reporting on the outcomes of interest was considered to be minimal.

Finally, this study did not assess effectiveness outcomes, such as LDL-C reduction. Therefore, it is not possible to relate the effect of adherence to treatment to its clinical impact. Future real-world evidence studies will require simultaneously assessing both types of outcomes to conclude their association in real-life settings.

The present study provides information on treatment patterns and adherence to evolocumab in the treatment of hyperlipidaemia in Colombia that is consistent with real-world studies of evolocumab conducted in other countries. In Colombian clinical practice, adherence to evolocumab increases the longer the enrolment on the PSP, despite the high frequency of problems accessing the medication, a critical finding considering that it is a chronic treatment.

ConclusionDespite the high efficacy and safety profile of evolocumab therapy, the PSP provides insight into aspects related to the dispensing, formulation, and compliance processes of evolocumab treatment and reveals local barriers that limit therapeutic persistence in Colombia and thus reduce the potential clinical benefits in patients with a high or very high cardiovascular risk profile with dyslipidaemia.

The overall adherence found in this study (above 70%) is similar to findings reported in other real-life studies with iPCSK9. However, the causes of low compliance in certain patients are different, including a high number of administrative and medical reasons for discontinuing or abandoning evolocumab treatment.

Compliance and persistence rates were higher in patients who were on the evolocumab PSP for longer, indicating the effectiveness of the programme in improving treatment adherence.

FundingThis work was funded by Amgen Biotecnológica SAS.

Conflict of interestsThe author Ángel Alberto García-Peña has no conflict of interest to declare. The authors Mariana Pineda-Posada, Carol Páez-Canro, César Cruz declare that they are part of the medical team of Amgen Biotecnológica SAS and that the activities carried out in the study are included in their employment contract. Daniel Samacá-Samacá is a consultant for IQVIA and the activities of methodological consultancy, development of statistical analyses, and medical writing are included in his work duties.

We would particularly like to thank the PSP and pharmacovigilance team at Amgen (Colombia) for their continued support in bringing this study to fruition.