The irruption of lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)) in the study of cardiovascular risk factors is perhaps, together with the discovery and use of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (iPCSK9) inhibitor drugs, the greatest novelty in the field for decades. Lp(a) concentration (especially very high levels) has an undeniable association with certain cardiovascular complications, such as atherosclerotic vascular disease (AVD) and aortic stenosis. However, there are several current limitations to both establishing epidemiological associations and specific pharmacological treatment. Firstly, the measurement of Lp(a) is highly dependent on the test used, mainly because of the characteristics of the molecule. Secondly, Lp(a) concentration is more than 80% genetically determined, so that, unlike other cardiovascular risk factors, it cannot be regulated by lifestyle changes. Finally, although there are many promising clinical trials with specific drugs to reduce Lp(a), currently only iPCSK9 (limited for use because of its cost) significantly reduces Lp(a).

However, and in line with other scientific societies, the SEA considers that, with the aim of increasing knowledge about the contribution of Lp(a) to cardiovascular risk, it is relevant to produce a document containing the current status of the subject, recommendations for the control of global cardiovascular risk in people with elevated Lp(a) and recommendations on the therapeutic approach to patients with elevated Lp(a).

La irrupción de la lipoproteína (a) (Lp(a)) en el estudio de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular es quizás, junto con el descubrimiento y uso de los fármacos inhibidores de la proproteína convertasa subtilisina/kexina tipo 9, (iPCSK9), la mayor novedad en el campo desde hace décadas. La concentración de Lp(a) (especialmente los niveles muy elevados) tiene una innegable asociación con determinadas complicaciones cardiovasculares, como los derivados de enfermedad vascular aterosclerótica (EVA) y o la estenosis aórtica. Sin embargo, existen varias limitaciones actuales tanto para establecer asociaciones epidemiológicas como para realizar un tratamiento farmacológico específico. En primer lugar, la medición de la Lp(a) depende en gran medida del test utilizado, principalmente por las características de la molécula. En segundo lugar, la concentración de Lp(a) está determinada en más del 80% por la genética, por lo que, al contrario de otros factores de riesgo cardiovascular no puede ser regulada con cambios del estilo de vida. Finalmente, aunque existen múltiples ensayos clínicos prometedores con fármacos específicos para reducir la Lp(a), actualmente solo los iPCSK9 (limitados para su uso por su coste) reducen de forma significativa la Lp(a).

Sin embargo, y en línea con otras sociedades científicas, la SEA considera que, con el objetivo de aumentar el conocimiento sobre la contribución de la Lp(a) al riesgo cardiovascular, se considera relevante la realización de un documento donde se recoja el estado actual del tema, las recomendaciones de control del riesgo cardiovascular global en las personas con Lp(a) elevada y recomendaciones sobre la aproximación terapéutica a los pacientes con Lp(a) elevada.

Kare Berg was the first to identify the increased serum presence of an antigen that was highly impacted by inheritance and that he called apolipoprotein a [apo(a)] and found in low density lipoprotein (LDL) of patients with myocardial infarction.1–3 Various studies confirmed that apo(a) is part of a lipoprotein (Lp) which otherwise resembles LDL. Oddly, Lp(a) has only been identified in hedgehogs and in primates, including human beings.4

Structure, synthesis, and catabolismThe protein structure of Lp(a) is comprised largely of apolipoprotein B100 (apoB) and apo(a), and it is precisely this combination that is the hallmark of this lipoprotein.5 Cloning of the apo(a) (LPA) gene and its sequencing in 1987 revealed that it was a hydrophilic, highly glycosylated protein, highly homogenous with the plasminogen gene.6 It contains certain characteristic domains known as kringles, which are 80–90 amino acid structures organised in a triple loop. Apo(a) contiene two types of kringles (K), IV and V, as well as a mutated protease domain without any proteolytic activity.6 While there is only one copy of KV and the protease domain on each apo(a) molecule, there are 10 KIV kringle subtypes, numbered 1-10 (KIV1-10). All of them, except KIV-2, have a single copy per molecule. By contrast, KIV-2 can have anywhere from one copy to more than forty, but polymorphic variability can also occur within an individual by inheriting lpa from both parents.

The number of KIV-2 kringles determines the length and total molecular weight of apo(a), which varies between 300 and 800 KDa. Not only does the length and molecular weight of apo(a) depend on the number of KIV-2 copies, but KIV-2 is also an important inverse determinant of serum Lp(a) concentration.7 As a result, the more copies of KIV-2 in apo(a), the lower the serum concentration of Lp(a) in molar units.

The mechanisms of Lp(a) synthesis and catabolism have yet to be fully elucidated. Lp(a) is regarded as being primarily produced by the liver. The interaction across lysine-rich domains between apoB-100 and apo(a) precedes the formation of a single disulphide bond between both apolipoproteins, which may occur at the extracellular level.8 Lp(a) catabolism also appears to take place fundamentally in the liver, although the receptors involved have similarly not been identified. The LDL receptor does not appear to play a major role in the clearance of Lp(a)4 from the circulation. Some studies have detected small amounts of non-apoB-bound apo(a) in urine, albeit the role of the kidney in Lp(a) catabolism is likewise not clearly defined.9

Genetic and environmental determinants of Lp(a) concentrationGenetic determinants: number of KIV repeats and SNPApproximately 80% of Lp(a) concentration is determined by co-dominant inheritance in the LPA gene.4,10 It has been estimated that 19–70% of the variability in Lp(a) concentration depends on the number of KIV-2 repeats. For instance, short apo(a) isoforms (10 to 22 copies of KIV-2) are associated with 4–5 times higher Lp(a) concentrations than long isoforms (>22 copies of KIV-2).4,11 This is presumably due to decreased apo(a) synthesis efficiency in the long isoforms rather than to differences in catabolism. Nevertheless, there may be more than 200-fold differences in serum Lp(a) concentration between unrelated individuals with isoforms of similar length, as well as more than 2-fold differences in relatives with the same apo(a) isoforms.11 Therefore, genetic variants other than KIV-2 copy number also determine Lp(a)12 concentration. Numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that increase or decrease Lp(a) concentration have been documented, such as the rs10455872 and rs379822012 SNPs. Notably, some of the SNPs located in the LPA gene are inherited in linkage disequilibrium with the number of KIV-2 copies.

It is also worth pointing out that up to 70% of KIV-2 is encoded for hypervariable areas that are not easily accessible to standard sequencing technologies13; consequently, this is an issue that will require further study. Genetic variants at the APOE, CETP, and APOH loci may also modulate serum Lp(a) concentration, although to a lesser extent. For example, the APOE2 allele is associated with lower levels of Lp(a).4,11

Ethnicity is also a determinant of serum Lp(a) concentration, which is higher among people of Chinese, Caucasian, South Asian, and black ethnicity in ascending order. It would seem that these differences are chiefly dependent on the number of KIV-24,11 repeats. Lp(a) concentration is fairly stable throughout adulthood and slightly higher (5–10%) in women than in men.4,11

Environmental determinants: physiological (fasting, diet, exercise) and pathological (hepatic dysfunction, renal impairment, inflammation, and hormonal changes) determinantsAlthough not as well characterised as genetic factors and overall less important, environmental factors can also modify serum Lp(a) concentration, notably in certain physiological and pathological circumstances. Furthermore, there are still factors that have to do with Lp(a) concentration the origin and clinical relevance of which are also as yet not entirely established. One example is that an inverse relationship between Lp(a) concentration and triglycerides has been noted, especially when a person’s level of triglycerides exceeds 400 mg/dl.14

Lp(a) values are not substantially impacted by the fasting-postprandial cycle or by physical exercise.11 Likewise, diet also appears to have no significant affect on Lp(a) concentrations, with decreases of 10–15% reported in carbohydrate-poor and fat-rich diets. Pregnancy doubles Lp(a) concentrations, yet there is only a slight increase in Lp(a) with menopause.11

As an organ of Lp(a) synthesis, severe liver disorders can alter Lp(a) concentration.11 Serious kidney disease tends to raise Lp(a) through increased hepatic synthesis associated with proteinuria or decreased renal catabolism.15 Chronic inflammatory diseases also elevate Lp(a) levels, whereas in severe clinical conditions, involving life-threatening events and acute phase reaction, Lp(a) concentrations decline.16,17

A number of hormones that drive lipoprotein concentrations also exert an effect on Lp(a).11 Hence, thyroid disorders have the same effect on Lp(a) levels as they do on LDL cholesterol. That is to say, hyperthyroidism decreases it, while hypothyroidism increases it. Growth hormone and hormone replacement therapy at menopause cause Lp(a) concentrations to rise and fall, respectively.11

To conclude this section, it is important to remember that, as previously stated, changes due to hormones and acute phase inflammatory reactiosn are fairly minor if compared to the levels determined by genetics.

Pathogenic factors (arteriosclerosis)Despite the fact that serum Lp(a) concentrations are lower than LDL, there is evidence that the pathogenicity of Lp(a) may, in fact, be higher.18 One explanation for this is the tendency for Lp(a) to accumulate on the arterial wall, which is facilitated by the binding of the lysine-rich domain of KIV-10 of apo(a) to the LDL domain to the proteins of the extracellular matrix19 and another explanation might be the capacity Lp(a) has both to initiate vascular inflammation as well as to promote progression of the atherosclerotic lesion.20 Oxidised phospholipids, which are primarily transported by Lp(a) in serum, have been hypothesised to be important mediators in proinflammatory and procalcifying mechanisms induced by Lp(a), whether in the atherosclerotic injury of the vascular wall or in the cardiac valves.21

Lp(a) may also exhibit prothrombotic capacity either by increasing coagulation or by inhibiting fibrinolysis (e.g., by competing with plasminogen). Nevertheless, drastic changes in Lp(a) levels due to treatments do not change ex vivo fibrinolytic activity.22 In this sense, there is no epidemiological evidence of an association between elevated Lp(a) and increased risk of venous thrombosis, a context that differs from atherosclerotic lesions.23

Laboratory methodology used in Spain to determine Lp(a)One of the greatest challenges for the coming years with respect to the use of Lp(a) as a predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk and potential therapeutic target is to establish a standardised approach to quantifying it in clinical practice. This would enable comparisons to be made between diverse populations and allow consistent reference levels and recommendations to be established. As we will see later on, this has not yet been achieved, and there are multiple methods of determination, and even different non-interchangeable units of measurement (mg/dl, nmol/l) that hinder to some extent the interpretation of laboratory results and the possibility of implementing treatment interventions. No special conditions are needed per se and it can be measures in either fasting or non-fasting conditions, although determination during acute processes is not recommended, with the exception of acute coronary syndrome.24

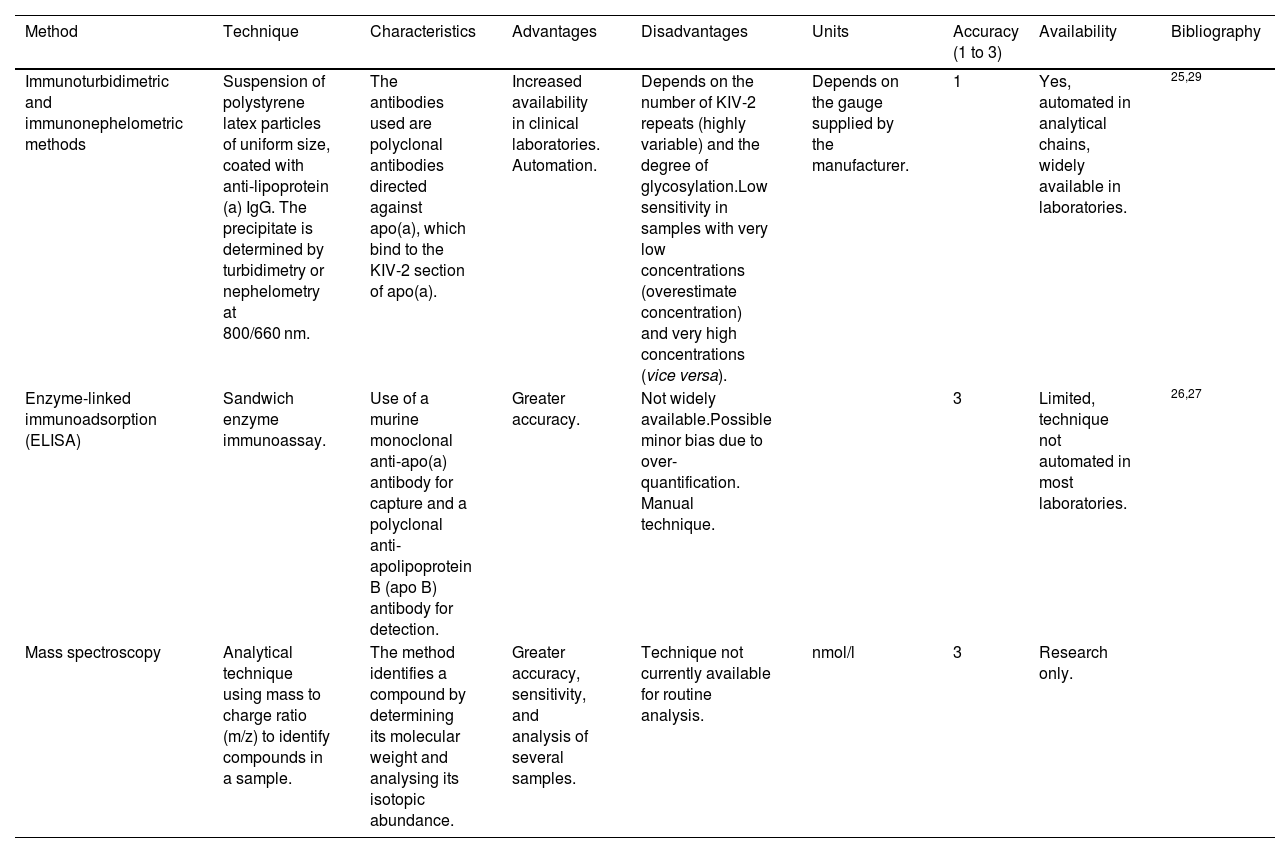

TechniqueFor the most part, two types of measurement methods are used in Spain: those based on detecting KIV-2 and those that focus on quantifying ApoA and ApoB molecules (explained in greater depth in Table 1).

Tests available in Spain to determine Lp(a).

| Method | Technique | Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages | Units | Accuracy (1 to 3) | Availability | Bibliography |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoturbidimetric and immunonephelometric methods | Suspension of polystyrene latex particles of uniform size, coated with anti-lipoprotein (a) IgG. The precipitate is determined by turbidimetry or nephelometry at 800/660 nm. | The antibodies used are polyclonal antibodies directed against apo(a), which bind to the KIV-2 section of apo(a). | Increased availability in clinical laboratories. Automation. | Depends on the number of KIV-2 repeats (highly variable) and the degree of glycosylation.Low sensitivity in samples with very low concentrations (overestimate concentration) and very high concentrations (vice versa). | Depends on the gauge supplied by the manufacturer. | 1 | Yes, automated in analytical chains, widely available in laboratories. | 25,29 |

| Enzyme-linked immunoadsorption (ELISA) | Sandwich enzyme immunoassay. | Use of a murine monoclonal anti-apo(a) antibody for capture and a polyclonal anti-apolipoprotein B (apo B) antibody for detection. | Greater accuracy. | Not widely available.Possible minor bias due to over-quantification. Manual technique. | 3 | Limited, technique not automated in most laboratories. | 26,27 | |

| Mass spectroscopy | Analytical technique using mass to charge ratio (m/z) to identify compounds in a sample. | The method identifies a compound by determining its molecular weight and analysing its isotopic abundance. | Greater accuracy, sensitivity, and analysis of several samples. | Technique not currently available for routine analysis. | nmol/l | 3 | Research only. |

Lp(a): lipoprotein (a).

Immunoturbidimetric and immunonephelometric methods are the most widely used in our setting. The main reature of those available at most centres is that they rely on immunoglobulins that bind to the KIV-2 section of apo(a). As previously commented, KIV-2 is a sequence that can be present in more or fewer repeats within the apo(a) particle (see section “Definition, structure, and regulationre), which may limit the accuracy of the test to some degree. These methods are evolving in order to be able to react with antibodies against a uniquely represented structure on the Lp(a) molecule, such as the KV or the protease domain.25

The enzyme-linked immunoadsorbent assay (ELISA) while theoretically more accurate, is less available. After trapping Lp(a) by means of an anti-apo(a) antibody, it is then quantified using an anti-apo B antibody, given that there is a single molecule of each in the Lp(a) particle. This eliminates the inaccuracy due to the measurement of variable sequences (which determine the different isoforms) within the apo(a)26 molecule (Table 1). Some authors have pointed out the possible overestimation of Lp(a) in assays of this type, based on apo(a) capture/ apoB detection, as a result of the marginal non-covalent binding of Lp(a) particles to triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in triglycerides.27

As for existing methods, and with respect to those based on KIV-2 detection, it is worth bearing in mind that Lp(a) concentrations are strongly determined by genetics, and scarcely affected by diet or lifestyle modification. Part of the genetic influence on Lp(a) in descendants is the number of KIV-2 repeats (see section on Lp(a) genetics). Particles containing more KIV-2 repeats are larger and heavier (an estimated mass difference of 19% has been reported between an Lp(a) particle with six KIV-2 repeats in apo(a) compared to Lp(a) having 35 KIV-2 repeats; therefore, Lp(a) measurement could have artefacts when using assays that are not isoform-independent.28 These measurement errors mostly affect quantifications with extreme results, underestimating concentrations of samples from individuals with small Lp(a) isoforms (associated with higher Lp(a) levels) and vice versa.29 This is of particular concern inasmuch as it would underestimate the risk of subjects who have small Lp(a) isoforms and vice versa.11

Units and measurement conversionMost current consensus statements, therapeutic strategies, and clinical practice guidelines express Lp(a) measurements in mass units (mg/dl). This is primarily on educational and historical grounds, because clinicians are more accustomed to using them. Consequently, systems are often used to convert the original units expressed by the aforementioned different analytical tests. Nevertheless, in this case, this approach is not actually correct from a metrological point of view. The reason is that these analytical tests only determine the concentration of the protein fraction of apo(a), and not the mass of the other components of the Lp(a) particle, such as cholesterol, cholesterol esters, phospholipids, triglycerides, and carbohydrates. Furthermore, when converting nmol/l to mg/dl, a second metrological error is made, in that apo(a) isoforms have a variable molecular weight, which does not lend itself to a one-to-one conversion between mass and molar units.

For practical purposes, the remainder of this document will continue to use the units commonly expressed in the literature (mg/dl), although the reader is made aware that this approach introduces a certain margin of error, especially at the extreme values of Lp(a). This is likely to improve with the introduction of more accurate, isoform-sensitive tests based on apo(a) molar units that reflect the amount of Lp(a) particles present in an individual’s serum/plasma, regardless of the number of KIV-2 repeats, the degree of N- and O-glycosylation of apo(a), or the lipid composition of Lp(a). This will make it possible to define more precise limits of normality and cut-off points to establish the different therapeutic actions expressed in the correct units (nmol/l).29–33

Several ongoing initiatives in this direction attempt to solve the metrological problems in the more accurate measurement of Lp(a) by manufacturing materials calibrated in molar units traceable to verified references (WHO/IFCC, Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratory (NLMDRL), International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC) [sic].34

To conclude, a number of papers have been presented recently that further the protocolisation of Lp(a) determination by mass spectrometry with the most advanced quality standards.35,36

Until such tests actually come to fruition, the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) recommends that specific reference values for the test performed be included in laboratory reports. While, as noted above, we do not recommend converting between units, we also admit that clinicians sometimes need to have some reference for their patient’s test result with respect to clinical practice guidelines and consensus. In this sense, conversion factors from mg/dL to nmol/L typically range from 1:2.0 to 1:2.511,37 although, as discussed, this conversion is not particularly accurate and should only be used as a rough approximation of the test result and probably only to determine whether a patient is in a very high or very low range.38 The reader should keep this in mind and therefore different conversion factors may appear in different parts of this document. This is due to the fact that we have endeavoured to respect the conversions made in the original articles.

In summary, and given the heterogeneity of Lp(a) determination at the present time, a few key concepts should be stressed, such as that serum Lp(a) concentrations should ideally be measured using a method that minimises the effect of isoform size by using appropriate antibodies with certified calibrators in order to trace Lp(a) values to the WHO/IFCC reference material, and that if the practitioner’s working laboratory does not have such methods, the accuracy of the test should be understood to be lower. Similarly, results should ideally be expressed in nmol/L of Lp(a) particles, and if other units are used, the reference limits for the test used should always be stated. Finally, it should be highlighted that the conversion from mass units to molar units or vice versa introduces a degree of inaccuracy, and that whenever used, it should always be clear that the results obtained are merely indicative.

Lipoprotein(a) and its role in vascular disease, aortic stenosis, and other diseasesSince the discovery of Lp(a), numerous epidemiological studies have been published correlating it with the risk of atherosclerotic vascular disease (AVD).1 The first prospective studies, conducted in the 1990s, revealed no consistent correlation with AVD or acute myocardial infarction (AMI), which is likely attributable to the use of inaccurate measurement methods.39 This led to a loss of scientific interest in Lp(a) in the years that followed, with a significant decrease in publications on Lp(a) during that period. However, more recent epidemiological and genetic studies point toward a causal association between elevated Lp(a) levels, AVD, aortic stenosis (AS), as well as other disease conditions. Most people have either low or very low Lp(a) levels, however, it is estimated that 20–25% have levels above 50 mg/dl, a value that the European Atherosclerosis Society believe confers an increased risk of CVD morbidity and mortality.11

Epidemiological studies linking Lp(a) to coronary heart diseaseLarge prospective general population studies were published in the first decade of this century. The Copenhagen City Heart Study followed 9,339 Danish individuals for 10 years, and found that increased Lp(a) concentrations were independently associated with the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), whereas the risk of AMI increased by 9% for every 10 mg/dl increase in Lp(a)40 concentration; thus, in comparison to a concentration of Lp(a) < 5 mg/dl, an Lp(a) value of ≥ 120 mg/dl resulted in an almost 4-fold greater relative risk of myocardial infarction. The same study also demonstrated that elevated Lp(a) was associated with a higher rate of CV and all-cause mortality, irrespective of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration.41 In 2009, a meta-analysis of 36 prospective cohorts that had enrolled 126,634 participants without prior AVD performed by the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration confirmed a continuous and independent, albeit modest, correlation between Lp(a) concentration and the risk of non-fatal AMI and CV death.42 Despite the fact that this meta-analysis involved mostly Caucasian studies, other racial groups were also represented, and no differences were identified regarding the risk estimates for different ethnic groups. In the subsequent Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study conducted in both white and black populations, Lp(a) levels were positively associated with AVD with equal strength in both racial groups, albeit median Lp(a) values were 2–3 times higher in blacks than in whites.43 An analysis of 460,506 middle-aged individuals from the UK Biobank database with a median follow-up time of 11.2 years showed a linear association between Lp(a) concentration and the risk of AVD (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.10–1.12) for every increment of 50 nmol/l.44

Similarly, in individuals with familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH), an increased risk of coronary heart disease has also been observed in those whose Lp(a) concentrations exceed 50 mg/dl in comparison to people with FH and Lp(a) levels of less than 50 mg/dl.45

Likewise, elevated Lp(a) levels have been implicated in the recurrence of CV events in subjects with established CHD, although the data regarding these populations have been inconsistent.46 In patients undergoing secondary prevention in Denmark, increasing Lp(a) values exhibited an increased risk of recurrence, and it was estimated that a 50 mg/dl (105 nmol/l) reduction over a 5-year period would be needed in order to achieve a 20% reduction in the rate of CV events.47 In a meta-analysis of 18,979 individuals, Lp(a) > 80th percentile levels were predictive of recurrent CV events in statin-treated CHD patients and were associated with 40% more major CV events (MACE); but only when baseline c-LDL was ≥ 130 mg/dl.48

In short, epidemiological studies prove that an increase concentration of Lp(a) entails a greater risk of AVD, the magnitude of which is even greater among populations in primary prevention. The association between genetic variants associated with high Lp(a) values and CV envents disappears once you adjust for Lp(a) level, which suggests a direct pathogenic role of Lp(a) in the development of CHD.49

Epidemiological studies linking Lp(a) to aortic stenosis (AS)Calcified AS is the most common form of acquired heart valve disease that requires intervention. The prevalence of AS is estimated to be 2–4% in persons over the age of 65 years and the number of people with an indication for aortic valve replacement is expected to double by 2050.50 In recent years, the understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to the development of this disease has evolved from degenerative calcification to an active process that is derived from the interaction of genetic factors and chronic inflammation, and driven by risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and hypercholesterolaemia. While there is an overlap of risk factors between calcified AS and CHD, ≈50% of patients with calcified AS do not experience concomitant CHD. Moreover, statins, which have a significant beneficial effect on CHD, have so far not been shown to halt the progression of AS,51,52 suggesting the existence of other pathophysiological factors in calcified AS.

A paper published in 2013 was the first to establish that Lp(a) levels stemming from genetic variations in the LPA locus were associated with aortic valve calcification and clinical AS.53 A posterior study among 77,680 participants, combining data from the Copenhagen City Heart Study and the Copenhagen General Population Study, found that elevated Lp(a) concentrations correlated with an increased risk of AS, and that Lp(a) > 90 mg/dl values increased the risk of AS by a factor of 3.54 These observations have been corroborated in subsequent epidemiological studies. More recently, a systematic review of 21 studies, including case-control, prospective and retrospective observational, and genetic studies, has reported a significant association between elevated Lp(a) and calcified AS; in addition, increased Lp(a) predicts accelerated haemodynamic progression of AS as well as a greater risk of aortic valve replacement, most notably in young patients.55 Increased Lp(a) is associated with aortic valve calcification especially in younger individuals (45–54 years), for whom the risk triples when Lp(a) levels surpass the 80th percentile relative to lower levels (15.8% vs. 4.3%).56 In a substudy of the FOURIER trial, which included 27,564 AVD patients taking statins, elevated Lp(a) levels, but not c-LDL values, were associated with an increased risk of subsequent AD events, either progression or the need for aortic surgery with valve replacement.57

Therefore, increased Lp(a) values are associated with the development of AS, especially in young people, with a greater speed of progression and higher risk of valve replacement surgery.

Epidemiological studies that link Lp(a) to heart (FH) and atrial fibrillationThe combined analyisis of the Copenhagen General Population Study and the Copenhagen City Heart Study revealed that Lp(a) levels above the 75th percentile and certain risk genotypes in the LPA gene (such as rs3798220 and rs10455872) increased the risk of AMI and AS, and that concentrations greater than the 90th percentile correlated with a higher risk of FH, which appeared to be mediated in part by the greater risk of AMI and AS.58

The association between AVD and atrial fibrillation has been well recognised. However, whether Lp(a) is an independent causal factor for atrial fibrillation remains an open question. In a study from the UK Biobank cohort, which recruited more than 500,000 people between the ages of 37 and 73 years across the UK between the years 2006 and 2010, the authors concluded that a potential involvement of Lp(a) in the risk of developing atrial fibrillation could be established, which was partially independent of the atherosclerotic effect of Lp(a).59

Epidemiological studios that link Lp(a) to atherosclerosis in other territoriesFrom a pathophysiological perspective, the relationship between Lp(a), stroke, and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is plausible, given that atherothrombosis is the main aetiopathogenic basis of both conditions, similar to what happens in coronary heart disease. Thus, the atherogenic effect of Lp(a) would extend to the different arterial territories, either through the LDL that is part of the Lp(a) molecule, the pro-inflammatory effect of the oxidised phospholipids it contains, or the antifibrinolytic and thrombogenic actions of apo(a).4

The connection between stroke and CVD risk factors is more complex than in the case of CHD or PAD. This is due to the fact that stroke can result from a variety of aetiologies in addition to atherothrombosis, including haemorrhage, embolism, or arteriolar hyalinosis. Nonetheless, there is a large body of evidence from epidemiological research that has established that increased Lp(a) concentrations are associated with an increased risk of ischaemic stroke. Large-scale studies have demonstrated an association between Lp(a) values and the risk of stroke. In the Copenhagen General Population Study (n = 49,699) and the Copenhagen City Heart Study (n = 10,813)60 serum Lp(a) levels were gradually, directly, and continuously associated with the risk of stroke. This correlation has been confirmed in large meta-analyses, including the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, with a follow-up of 1.3 million person-years, in which a continuous relationship between Lp(a) concentration and stroke risk was noted.42 In this meta-analysis, a 3.5-fold increase in Lp(a) concentration (1 standard deviation) was associated with a risk of ischaemic stroke of 1.10 (95% CI 1.02–1.18), which was independent of other CVD risk factors. Similarly, in a meta-analysis of 20 studies (n = 90,904 individuals), elevated Lp(a) values were associated with an odds ratio (OR) of ischaemic stroke of 1.41 (95% CI 1.26–1.57) in case-control studies and 1.29 (95% CI 1.06–1.58) in prospective studies.61 Consistent with these data, Lp(a) concentrations are also related to the residual risk of stroke recurrence in patients with a first ischaemic stroke,62 although this relationship might be attenuated in patients with low levels of c-LDL or inflammatory markers. 63

The connection between Lp(a) and PAD has been documented in prospective studies of large population groups, including the Edinburgh Artery Study,64 the Scottish Heart Health Extended Cohort Study,65 and the EPIC study.66 This last study was conducted in a large cohort of healthy individuals (n = 18,720) and a 2.7-fold increase in Lp(a) concentration was associated with a 1.37 (95% CI 1.25–1.50) increased risk of PAD, independent of c-LDL values.

In an analysis of the Spanish FRENA registry comprised of 1,503 stable outpatients with CAD, cerebrovascular disease, or PAD, those with Lp(a) concentrations of between 30 and 50 mg/dl had a higher rate of limb amputations than those with concentrations of less than 30 mg/dl (relative risk [RR]: 3.18; 95% CI: 1.36–7.44). The risk of amputation was even higher when Lp(a) levels exceeded 50 mg/dl (RR: 22.7; 95% CI: 9.38–54.9).67 Similarly, a systematic review that included 493,650 subjects found that elevated Lp(a) was associated with an increased risk of intermittent claudication (RR: 1.20), progression of PAD (RR: 1.41), restenosis (RR: 6.10), PAD-related death and hospitalisation (RR: 1.37), amputation (RR: 22.75), and lower limb revascularisation (RR: between 1.29 and 2.90 depending on factors such as the Lp(a) cut-off point and years of follow-up), which was found to be independent of traditional CVD risk factors.68

The higher the concentration of Lp(a), the greater the risk of clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis in more than one arterial territory, in other words generalised atherosclerosis, and the more severe the clinical manifestations of the disease,69 including higher all-cause mortality.70 Patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention who have PAD have higher Lp(a) values than those without PAD.71 In the same manner, individuals undergoing intervention for PAD or carotid surgery who exhibit Lp(a) > 30 mg/dl have triple the risk of stroke, AMI, or CVD-related mortality (95% CI: 1.5–6.3) than those whose Lp(a) levels are within the reference interval.70 Increased Lp(a) titres are also found to be associated with a greater risk of restenosis requiring re-intervention or amputation following arterial revascularisation interventions in the lower limbs.72 In these cases, elevated Lp(a) concentrations entail a greater risk of stroke, CHD, or CVD-related mortality. Finally, some case-control studies suggest that higher Lp(a) levels may be associated with aortic dissection.73

In short, increased Lp(a) concentrations are associated with a greater risk of atherothrombotic stroke and PAD, as well as a higher speed of progression and risk of amputation in people with PAD.

Epidemiological studios that link Lp(a) to diabetesStudies carried out in different populations have implied that there is an inverse relationship between Lp(a) concentrations and the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nevertheless, this relationship is not linear over the entire distribution of Lp(a) values, but is pronounced at very low Lp(a) concentrations and no longer evident at intermediate or high concentrations.74 In a case-control study of 143,087 Icelandic individuals, 10% of those having the lowest Lp(a) concentrations (<3.5 nmol/l) had a higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (OR: 1.44; p < 0.0001). Nevertheless, in those who had concentrations exceeding the median, the risk of diabetes was not associated with Lp(a)75 concentrations. Another prospective study in the general population also found that Lp(a) concentrations in the lowest quintile (<10 nmol/l) were associated with an increased risk of diabetes and the risk was further increased in those with even lower Lp(a) concentrations.76 In another meta-analysis carried out in 2017,77 individuals with low Lp(a) values, between 3 and 5 mg/dl, were found to have a 38% higher risk of diabetes than those with values between 27 and 55 mg/dl.

It appears that only part of the association of Lp(a) with diabetes is attributable to a causal relationship, and it has not been possible to define whether the relationship is due to Lp(a) concentrations, to the length of apo(a) isoforms, or to a combination or interaction between both. The relevance of deciphering whether there is a causal relationship between very low Lp(a) concentrations and diabetes risk lies in the fact that, if there is strong evidence of such a relationship, it might be worth considering whether lowering Lp(a) to very low concentrations with the new drugs that are in the pipeline could increase the risk of diabetes. All in all, data from epidemiological studies imply that to increase the risk of diabetes, Lp(a) concentrations would have to be lowered to extremely low levels, which seems unlikely.74 Furthermore, it has been well documented that excess Lp(a) predisposes to micro- and macrovascular complications among people with diabetes, and analyses of large clinical trials with iPCSK978 suggest that in diabetic or pre-diabetic individuals, the potential diabetogenic risk of lowering Lp(a) would be far outweighed by the CVD benefit of markedly lowering atherogenic cholesterol.79

Genetic contribution of Lp(a) to CV complication ratesAs we have already seen, between 80–90% of a person’s Lp(a) concentration is genetically determined. This makes it possible to relate certain genetic variants in the LPA gene, which are primarily responsible for plasma Lp(a) levels, with the rate of CV complications without this relationship being affected by artifacts caused by external factors, which would indicate a causal relationship.80 In addition to the isoforms associated with genetic variants that regulate the number of KIV-2 repeats, other variants that have been linked to increases in Lp(a) levels are rs10455872 and rs3798220.

Genetic contribution of Lp(a) to CHDSeveral genetic association and Mendelian randomisation studies have established a link between various LPA variants and the severity and extent of atherosclerosis81 and the risk of developing vascular complications, mainly coronary heart disease. Many of these studies have been performed in the Danish population, and an inverse correlation has been evidenced between the number of KIV-2 repeats and the risk of AMI.82 However, while the association between CV and overall mortality with the number of repeats was observed, the same relationship was not evident for the rs1045587241 variant. In the same study, the amount of cholesterol in the Lp(a) particles was calculated. For the same amount of cholesterol, the extent of the association between Lp(a) and total and CV mortality was greater than that reported for LDL, which indicates that the effect of Lp(a) on mortality is greater than that attributable to its content in cholesterol.

Studies in other populations and large meta-analyses have corroborated these associations. In a meta-analysis of 40 studies, the presence of small apo(a) isoforms resulted in a two-fold increase in the rate of infarction and stroke compared to the presence of isoforms larger than 22 KIV-283 repeats. In other studies that have examined genetic variants associated with increased Lp(a), genetically predicted Lp(a) elevation was proven to be linked to CHD.49,82 Similarly, genetic variants associated with elevated Lp(a) also predict CHD risk in subjects already treated with statins, irrespective of the decrease in c-LDL brought about by the statins.84

Other studies have documented that allelic variants associated with small reductions in Lp(a) concentration are protective against the development of CHD.85,86 In fact, it has been shown that for every 10 mg/dl difference in genetically determined Lp(a) concentration, the rate of CHD is decreased by 5.8%.

Genetic scores have been developed with several Lp(a) variants to improve the prediction of the risk of CV complications.87 While their performance is good, the strength of the association is significantly weakened when Lp(a) concentration is included in the equation, which may limit their usefulness, in addition to the special issues surrounding conducting genetic studies of the hypervariable KIV areas.12

In the context of secondary prevention, LPA genetic variants have not been shown to impact mortality in patients with CHD.88

Genetic contribution of Lp(a) to aortic valve stenosisIn the EPIC study, the rs10455872 variant was identified as being associated with an increased incidence of AD,89 a finding that was substantiated in a meta-analysis that included data from the UK Biobank.90 In this work, the risk of AD increased by 10–30% for every 10 mg/dl increase in genetically determined Lp(a) concentrations. In contrast, the rs3798220 variant, which is less common in the general population, has been inconsistently associated with AD risk.90 In a large case-control study that included 3469 subjects with AD, both variants were linked to the risk of AD.91 The relationship of both polymorphisms has also been studied in a recent meta-analysis92 which revealed that the participants with these genetic variants exhibited faster progressions and a greater risk of clinical complications including deeath.

Genetic contribution of Lp(a) to other vascular diseasesIn the Multiancestry Genome-Wide Association Study of Stroke consortium (n ≤ 446,696), in which nine polymorphisms associated with Lp(a) concentrations were linked to the risk of different stroke subtypes, variants with elevated Lp(a) concentrations were associated with an increased risk of large artery stroke.93 For each one standard deviation increase in Lp(a) levels, the OR of large artery stroke was 1.20 (95% CI 1.11–1.30, p < 0.001). Nevertheless, the risk of small vessel stroke was lower (OR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.88–0.97); p = 0.001) and there was no association with ischaemic or cardioembolic stroke overall. This study also found an inverse relationship between genetically determined Lp(a) concentrations and the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease, an issue about which the data are somewhat debatable and may involve a number of confounding factors.93 The relationship between genetic variants and the risk of stroke has also been evidenced in the Danish population, where the number of KIV repeats and the rs10455872 variant are associated with a 20% and 27% increased risk of stroke, respectively.60

Genetically dictated elevation of Lp(a) has also been associated with the risk of developing heart failure,58 an effect that is partially mediated by the higher risk of CHD and AD.

Similarly, the LPA gene has also been implicated in the development of PAD in Mendelian randomisation and genome-wide association studies.23,94–96 In reference to the latter, the Million Veteran Program examined the association of 32 million variants of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequences with PAD (31,307 cases and 211,753 controls) in individuals of European, African, and Hispanic ancestry.95 The results were replicated in an independent sample of 5,117 cases of PAD and 389,291 controls from the UK Biobank. Nineteen PAD-associated loci were identified, including 18 not previously identified. These included loci in the LPA gene, which provides further corroboration that Lp(a) is associated with atherosclerosis in the lower limbs.

Consequently, Lp(a) should be regarded as a valuable biomarker to assess the risk of atherothrombotic stroke and PAD. With new drugs currently in the pipeline, Lp(a) is likely to be a therapeutic target in the primary and secondary prevention of these conditions.

Genetic contribution of Lp(a) to other diseasesA minor risk of diabetes has been reported97 with increased Lp(a) concentrations, which appears to be predominantly dependent on the genetic variant, specifically on the number of KIV-2 repeats.

Finally, controversy continues to surround the link between Lp(a) and the risk of venous thromboembolic disease. Despite the number of type 2 KIV repeat being inversely correlated with said risk, 98 Mendelian randomisation studies do not appear to confirm this link.80

Lp(a) measurements: when and in whomLp(a) levels are currently of interest for two main reasons: 1) to improve CV risk estimation in conjunction with other risk factors; 2) to evaluate an emerging risk factor that is fairly stable over time, enabling the population to be identified, with a view to potential future treatment approaches. The inexistence of effective treatments to substantially lower Lp(a) concentration (in particular, the absence of intervention studies with relevant clinical endpoints, specifically CV events) and the challenges involved in standardising Lp(a) measurements have delayed the systematic incorporation of Lp(a) measurement into CVD prevention guidelines.11,99–104

The renewed interest in Lp(a) as an independent vascular risk factor and the expectations of lowering Lp(a) levels by pharmacological means derived from early clinical trials have prompted the gradual incorporation of the proposal to measure Lp(a) levels in selected patients. Initial recommendations were focused on specific circumstances: early CVD (personal or family history), especially in the absence of other CV risk factors, family history of elevated Lp(a), familial hypercholesterolaemia, and poor lipid-lowering response to statins.11,99–104 Given the increased accessibility of Lp(a) measurement in conventional laboratories and the growing recognition of its prognostic value from observational studies, the current trend, initiated by the Canadian guidelines, is to include Lp(a) determination as part of an initial overall CV risk assessment in all patients.11,102,105 Considering that Lp(a) levels are genetically influenced and generally remain stable throughout life, a single measurement is generally deemed sufficient for clinical decision making.11,106 That being said, it is reasonable to contemplate performing a “confirmatory» measurement in certain circumstances: very high levels, doubts regarding the reliability of the method used, coexistence with situations capable of affecting Lp(a) values, such as advanced renal failure or nephrotic syndrome, if the first measurement was performed in childhood, pregnancy, significant hepatocellular/thyroid dysfunction, sepsis, or an acute inflammatory process, as addressed in the Supplementary material, Appendix A, Table S1.

This is the approach that has been accepted in the recent consensus document regarding lipid profile co-led by the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis (SEA), the Spanish Society of Laboratory Medicine, and the Spanish Society of Cardiology99 in collaboration with 15 scientific societies.

In people undergoing secondary prevention whose Lp(a) levels are not known, it is essential that these levels be determined, first of all, due to their prognostic value, which may point toward the advisability of bolstering preventive or therapeutic measures, such as the use of iPCSK9.107 In addition, it may serve to identify candidates for clinical trials or emerging treatments that specifically target the reduction of Lp(a) levels.

As previously noted, 80% of Lp(a) concentrations are determined by genetics. Whether Lp(a) genotyping offers superior prognostic value to direct measurement of circulating Lp(a) is open to question. While certain genetic polymorphisms (SNPs rs10455872 and rs3798220) are relatively widespread and associated with ‘small’ Lp(a) and higher circulating levels, more than 70% of the variability (> 500 variants) are encoded in the hypervariable regions of the KIV-2 repeats, and their determination is especially problematic with conventional sequencing technologies.11,12 Furthermore, other genes (APOE, CETP, APOH loci) are associated with changes in Lp(a) concentration. Finally, genotyping has not been proven to yield additional prognostic information to Lp(a) concentration determination; it is therefore not deemed necessary outside the context of research studies.108

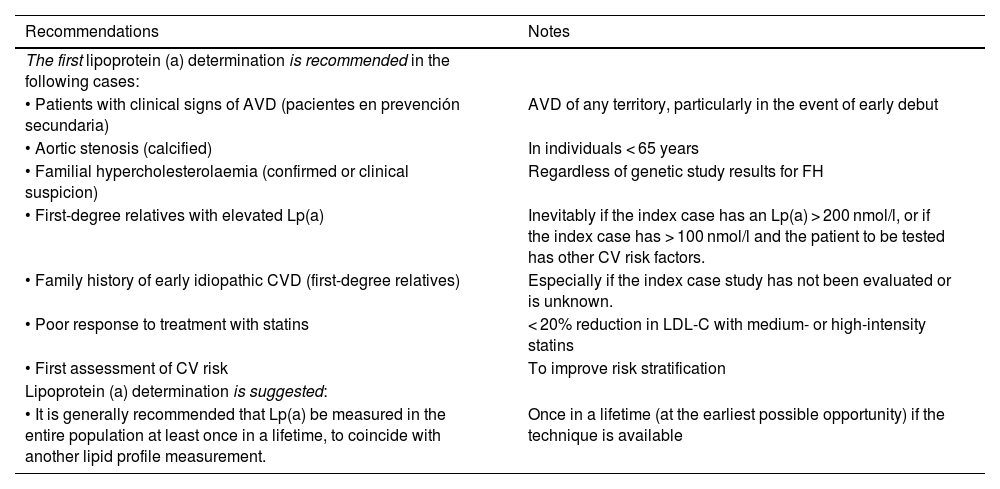

Table 2 summarises the recommendations and suggests concerning conducting an initital Lp(a) determination put forth by the SEA.

Recommendations for the first Lp(a) determination.

| Recommendations | Notes |

|---|---|

| The first lipoprotein (a) determination is recommended in the following cases: | |

| • Patients with clinical signs of AVD (pacientes en prevención secundaria) | AVD of any territory, particularly in the event of early debut |

| • Aortic stenosis (calcified) | In individuals < 65 years |

| • Familial hypercholesterolaemia (confirmed or clinical suspicion) | Regardless of genetic study results for FH |

| • First-degree relatives with elevated Lp(a) | Inevitably if the index case has an Lp(a) > 200 nmol/l, or if the index case has > 100 nmol/l and the patient to be tested has other CV risk factors. |

| • Family history of early idiopathic CVD (first-degree relatives) | Especially if the index case study has not been evaluated or is unknown. |

| • Poor response to treatment with statins | < 20% reduction in LDL-C with medium- or high-intensity statins |

| • First assessment of CV risk | To improve risk stratification |

| Lipoprotein (a) determination is suggested: | |

| • It is generally recommended that Lp(a) be measured in the entire population at least once in a lifetime, to coincide with another lipid profile measurement. | Once in a lifetime (at the earliest possible opportunity) if the technique is available |

c-LDL: concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CV: cardiovascular; CVD: cardiovascular disease; AVD: athersclerotic vascular disease; FH: familial hypercholesterolaemia; Lp(a): lipoprotein (a).

As a general rule, in light of the stability of Lp(a) levels throughout a person’s lifetime, there is no need for repeated measurements of Lp(a) levels.11,106 Nevertheless, it is reasonable to schedule a repeat determination in clinical circumstances in which there may be significant changes (Supplementary material, Appendix A, Table S1). The most pronounced changes are likely to arise in advanced renal failure (particularly in subjects undergoing peritoneal dialysis) and nephrotic syndrome,15,100 in which case a reassessment is more merited. In all other clinical situations, these changes are quite minor with a very modest impact on the estimation of CV risk; thus, repeated Lp(a) measurement is not typically regarded as useful. In case of borderline values, a new measurement can be contemplated if the prior measurement was performed in childhood, pregnancy, hepatocellular dysfunction, in situations of frank hyper/hypothyroidism, sepsis, or serious acute inflammatory processes, and after menopause.11

Finally, it is clear that repeat Lp(a) testing will be mandatory in order to assess treatment response once treatment is available. Although at present, iPCSK9 are the only lipid-lowering drugs in routine use that have a relevant effect on Lp(a) (approximately 20% reduction),109 significant pharmaceutical development is currently underway with medicines intended deliberately to lower Lp(a) concentrations, as will be further elaborated in the relevant chapter of this document.

These recommendations and suggestions are summarised in the Suppñemental material, Appendix A Table S1.

The importance of including Lp(a) when estimating CV riskLp(a) conferred risk assessment: threshold versus continuous rate of riskThe relationship between Lp(a) and CVD risk has been explored from two methodological perspectives. On the one hand, by attempting to identify certain cut-off points or thresholds that distinguish risk categories, as has been done previously with other lipid particles, such as c-LDL, and, on the other hand, by assessing whether there is a continuous proportional relationship.

Under the first approach, the risk conferred by elevated Lp(a) has been gauged by defining different threshold or categorical concentrations. The Copenhagen City Heart Study82 found that there was a significant increase in the risk of myocardial infarction over a 16-year follow-up starting at the 66th percentile of Lp(a) levels in 7524 subjects (approximately equivalent to 30 mg/dl).

Under the second approach, the continuous relationship between Lp(a) and CV risk has been probed: one of the main studies in terms of sample size is from UK Biobank44 with 460,506 middle-aged subjects (40–69 years) with a follow-up of 11.2 years. This study revealed that, in the total cohort, every 50 nmol/l increase in Lp(a) concentration was correlated with an 11% increase in CVD risk (HR: 1.11 for CHD and ischaemic stroke) in the Lp(a) range of up to 400 nmol/l. This figure varied slightly depending on the Lp(a) concentration in the cohort. This figure differed slightly depending on statin use, history of previous events, and age, and was maintained for both sexes and for different LDL-cholesterol concentrations.

While there is sufficient evidence to contend that the relationship between Lp(a) levels and CVD risk is continuous, the thresholds or cut-off points have been assumed for practical reasons, similar to the CVD risk cut-off points that define the various risk categories based on c-LDL.

Nonetheless, it is evident that, although different thresholds determine different “categories”, the clinician must be aware that there is a continuous association between Lp(a) and CV risk, and adapt their therapeutic effort accordingly.

Lp(a)-based risk calculationsOf the many studies that have assessed the impact of elevated Lp(a) on CVD risk, the UK-Biobank-based study44 has developed an online calculator to estimate future risk of ischaemic heart disease and stroke, up to the age of 80 years, based on the following variables: sex, age, total cholesterol, LDL-C, LDL-C, systolic blood pressure, treatment for hypertension, body mass index, presence of diabetes, smoking, smoking cessation, and family history.110 Once the risk has been estimated, it can be adjusted to Lp(a) levels, knowing that for every 50 nmol/l increase, the risk is multiplied by 1.11. According to the authors of this website, the risk calculation is based on an artificial intelligence modality called Causal Artificial Intelligence, generated thanks to the participation of the company “DeepCausal AI”, whose website currently has no content other than the logo (https://deepcausalai.org/) at the time of writing.

In a Danish cohort40 of 8,720 participants from the general population recruited between 1991 and 1994 and followed up until 2011 without any losses that monitored the incidence of AMI and CHD, a Cox proportional risk regression model for each type of event with traditional risk factors (sex, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, smoking, and diabetes) and other models to which Lp(a) levels and/or Lp(a) risk genotype (KIV-2) and/or rs3798220 and rs10455872 polymorphisms have been added.

The diagnostic performance with the incorporation of the new markers was evaluated using the net reclassification index (NRI) and the integrated discrimination index (IDI) as well as changes in the C-index. For the 80th [Lp(a) ≥ 47 mg/dl] and 95th [Lp(a) ≥ 115 mg/dl] percentiles, the NRIs for myocardial infarction were 16% and 23%, and for CHD 3% and 6%, respectively. The authors provided beta coefficients for the regression models in their Supplementary material, although these models have yet to be validated in other populations.

In Bruneck’s Italian cohort111 of 826 subjects from the general population whose risk was calculated according to Framingham and whose Lp(a) > 47 mg/dl was included as an additional factor, a significant increase in CVD risk was observed (HR: 2.37). Therefore, the addition of this factor improved both NRI and IDI.

Improved risk classification of patients by adding Lp(a) levels to the SCORE system has also been investigated. Using data from 16,777 subjects from the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer (EPIC), in whom risk was calculated using SCORE and then modified to include the 30 mg/dl Lp(a) threshold (corresponding to the 80th percentile of that cohort), diagnostic discrimination was improved, especially in the intermediate risk group.112 In this group, the resulting NRI was 8.73%; this finding lends support to quantifying Lp(a), particularly in intermediate-risk subjects so as to be able to better adjust the therapeutic strategy.

None of the three previously mentioned studies provide complete risk assessment models; consequently, the only system currently available to the public for calculating CVD risk, including Lp(a), is the one accessible online at the following website: https://www.lpaclinicalguidance.com.

ThresholdsSeveral studies have assessed the CVD risk associated with different Lp(a) thresholds. For instance, Lp(a) > 120 nmol/l values in subjects with no CVD entail a risk measured as HR of 1.25 for PAD, 1.40 for CHD, 1.32 for AMI, 1.11 for ischaemic stroke, and 1.09 for CV mortality.87

Over the last few years, several consensus documents and clinical practice guidelines have recommended different risk thresholds. The National Lipid Association104 established that a threshold of 50 mg/dl or 100 nmol/l can be assumed to be a factor that increases risk and therefore recommends statin therapy. This figure is equivalent to the 80th percentile of the American Caucasian population. The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology regard threshold values of 50 mg/dl or 125 nmol/l as indicative of increased risk of CVD.113 The UK consensus has established the following risk levels based on Lp(a) concentrations: low CVD risk for values of between 30 and 90 nmol/l Lp(a), moderate risk between 90 and 200, high risk between 200 and 400, and very high risk for levels that exceed 400 nmol/l.100 The 2019 European guideline already established that Lp(a) > 180 mg/dl (430 nmol/l) concentrations impart a risk similar to that of patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia.102 The European Atherosclerosis Society in its 2022 consensus document11 established a ‘grey area’ between 30 and 50 mg/dl. Levels of less than 30 mg/dl (75 nmol/l) pose no significant increase in CVD risk, whereas concentrations of more than 50 mg/dl (125 nmol/l) represent a significant increase in CVD risk. This grey area may be relevant in the presence of other risk factors. Although there is no direct conversion between mg/dL and nmol/l, several authors have stated that a multiplicative factor between 2 and 2.5 is used in the conversion as mentioned in the corresponding section.

These data are evidence that there is an international consensus that Lp(a) < 30 mg/dl (75 nmol/l) constitutes a low risk threshold and levels exceeding 50 mg/dl (125 nmol/l) define an increased risk threshold. The threshold of 180 mg/dl (430 nmol/l) would delineate a very high risk equivalent to heterozygous FH.

Review of the impact of Lp(a) concentration on total CV riskThe epidemiology of CVD has taught us that serum Lp(a) concentrations do not follow a normal population distribution, exhibiting a clear deviation to the left. Consequently, and given that a substantial proportion of the general population has relatively low Lp(a) concentrations, clinical studies focus primarily on the upper tercile of Lp(a) concentration, where a greater than 20% increase in CV morbi-mortality risk has been proven.

From the foregoing, it is clear that Lp(a) is a risk factor for CVD in both primary and secondary prevention of CVD, even in the presence of low LDL-cholesterol levels. In the first clinical scenario, Lp(a) concentrations above the 75th percentile increase the risk of AD and AMI; levels above the 90th percentile are associated with an increased risk of heart failure,58 and only extreme levels above the 95th percentile are associated with an elevated risk of ischaemic stroke and CV mortality.41,60,83 In the context of secondary prevention, three meta-analyses have linked elevated Lp(a) to an increased risk of severe CV events, albeit there is some heterogeneity across studies.46,48,114 In patients with established CVD from the Copenhagen General Population Study47 and the AIM-HIGH,115 Lp(a) was found to be significantly associated with recurrence of major coronary events. Likewise, in a recent meta-analysis with individualised data from seven randomised, placebo-controlled trials of statin intervention in primary and secondary prevention, elevated baseline Lp(a) was independently and almost linearly correlated with CVD risk.116 On the other hand, we should not lose sight of the fact that very high Lp(a) (>180 mg/dl [>430 nmol/l]) concentrations identify individuals with a lifetime risk of CVD that is equivalent to untreated heterozygous FH.102

Existing data with respect to the addition of Lp(a) levels in CVD risk estimatorsThe addition of Lp(a) to CVD risk prediction algorithms has demonstrated variable effects, although on the whole, it can be concluded that, as with most biomarkers, it improves risk discrimination marginally. In a study of more than 28,000 women from the Women’s Health Initiative, Women’s Health Study, and Justification for Use of Statins in Prevention (JUPITER), Lp(a) was associated with CVD only in those with a baseline cholesterolaemia of more than 220 mg/dl, and the improvement in prediction was minimal.117

Reclassification of patients according to Lp(a) measurements has been addressed in two studies with prospective follow-up periods of 15 and 6 years.111,118 The addition of Lp(a) reclassified 15–40% of patients as high or low CV risk. More recently, Delabays et al.119 have illustrated that, in a country with low CV mortality such as Switzerland, the addition of Lp(a) to the SCORE model refined CV prevention, particularly in intermediate-risk individuals, with an 11.4% improvement in reclassification.

On this basis, the most recent EAS consensus11 on Lp(a) suggests defining what Lp(a) concentrations represent an increased risk for a given individual taking into account his or her overall CV risk. Based on the data obtained from the UK Biobank, an Lp(a) concentration of 50 mg/dl (115 nmol/l) increases a person's absolute CV risk with an overall 10% lifetime CV risk at baseline by 4% and by up to 10% in subjects with a baseline CV risk of 25%. An Lp(a) value of 100 mg/dl (230 nmol/l) would increase the absolute lifetime risk by 9.5% and 24%, respectively.11 In other words, the impact of Lp(a) concentrations on CV risk is also conditioned by the person’s overall baseline risk, which is why an individualised clinical approach is required taking into account the person’s characteristics, recommending more intensive management of risk factors for the same Lp(a) concentration in those people who are already at high risk.

Finally, the application of the new Lp(a) risk calculator proposed by the European Atherosclerosis Society consensus document as outlined in the section “Lp(a) risk calculators” highlights the following issues. Firstly, CVD risk is considerably underestimated if Lp(a) concentration is high and is not taken into account. Secondly, intervention on risk factors such as c-LDL cholesterol and blood pressure can mitigate at least part of the overall risk, even if Lp(a) levels remain unchanged. Furthermore, given that Lp(a) concentration is genetically determined, Lp(a) levels stay stable over time for most of the population. Therefore, the lifetime burden of individuals with elevated Lp(a) concentrations will be quite significant.

To conclude, despite the fact that there is no consensus regarding how to incorporate the risk attributable to elevated Lp(a) into conventional risk estimation models, the determination of Lp(a) levels can assist in fine-tuning CV risk estimation at least semi-quantitatively, with a grey area (30–50 mg/dL), moderate (≈50–100 mg/dl), high (100–200 mg/dl), and very high (>200 mg/dl) increased risk.

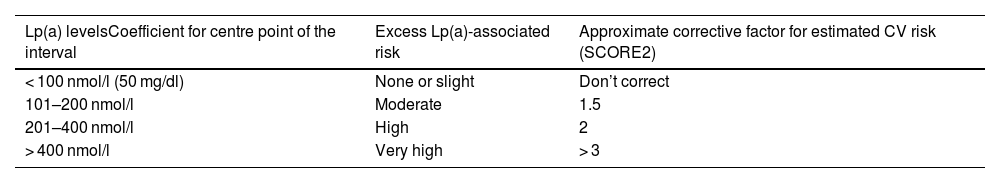

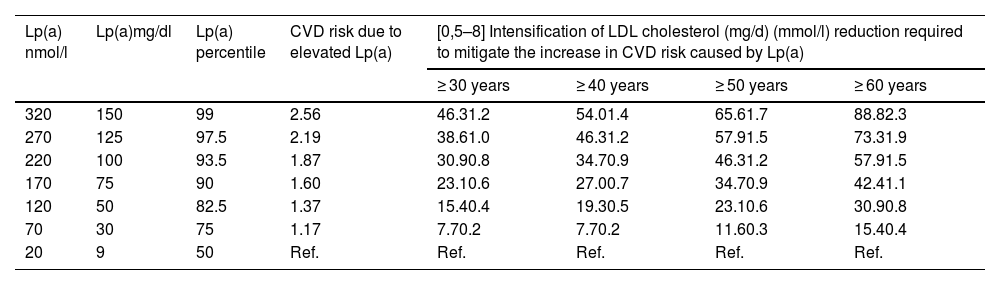

Recommendations for CV risk re-estimation using Lp(a)As previously discussed, we do not have epidemiological studies in our setting that would enable us to estimate the additional risk of our patients with different levels of Lp(a) with confidence. If we add the lack of standardisation of Lp(a) determination methods to this, it is impossible to offer a strict quantitative approximation. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to attribute an increase in vascular risk similar to that estimated for the UK Biobank Caucasian population and use it as a correction factor for the vascular risk estimated with the primary prevention tables (SCORE2, SCORE-OP).11,100 The correction factor makes it possible to modify the risk estimate and, as a result, to set treatment goals for LDL-C control in line with the recalculated risk.

Taking into account the preceding information, Table 3 outlines an approach to a semi-quantitative reassessment of CV risk by adding Lp(a), using correction coefficients calculated from the UK Biobank estimated CV risk changes for Caucasians with the British “lifetime” risk scales. As explained in the corresponding section, a single conversion between molar units and mass of Lp(a) is impossible and, for that reason, the correction coefficients should be used with caution. The table is a semi-quantitative approach, so the coefficients are an estimation of the mean values of the ranges reported and can be adjusted with a degree of further refinement as illustrated in the Supplementary material, Appendix A, Table S2.

Simplified model calculated based on the CV risk changes estimated in the UK Biobank for Caucasians with the British “lifetime” CV risk scales.

| Lp(a) levelsCoefficient for centre point of the interval | Excess Lp(a)-associated risk | Approximate corrective factor for estimated CV risk (SCORE2) |

|---|---|---|

| < 100 nmol/l (50 mg/dl) | None or slight | Don’t correct |

| 101–200 nmol/l | Moderate | 1.5 |

| 201–400 nmol/l | High | 2 |

| > 400 nmol/l | Very high | > 3 |

The proposed scale for Lp(a) in molar units and the mass units reported in the original consensus are given. As indicated in the corresponding section, a single conversion between Lp(a) molar and mass units is not possible and correction coefficients should be used with caution. The estimated CV risk to include the excess risk for Lp(a) is the multiplication of the risk estimate (e.g., SCORE2) by the correction coefficient in the table. A more detailed model is provided in the Supplementary material of this consensus.

CV: cardiovascular; Lp(a): lipoprotein (a).

In patients in secondary prevention, elevated Lp(a) also confers an additional risk and can therefore be taken into account to identify patients at extreme CV risk in whom more ambitious targets for LDL-C control (<40 mg/dl) and the early use of particularly intensive treatments, such as iPCSK9, can be proposed, as stated in the recommendations issued by the SEA.107

As mentioned in the corresponding section, there are currently no treatments available that have demonstrated a reduction in cardiovascular complications through treatments aimed at reducing Lp(a). Accordingly, both clinicians and patients should be encouraged to participate in clinical trials so as to be able to offer treatment based on the best scientific evidence in the coming years.

Finally, limited clinical evidence120 suggests that the use of lipoprotein apheresis in patients with CHD can improve their clinical outcome. There is no established indication for this treatment modality, and it could be considered on an individual basis for patients with extremely high levels of Lp(a) with established CVD, or even lower Lp(a) concentrations in the event of progression of vascular lesions despite adequate control of other CV risk factors.

Likewise, it should be remembered that regardless of the CV risk calculated without taking Lp(a) into account, several European guidelines have already made pronouncements regarding the increased risk conferred solely by exposure to very high levels of Lp(a). Accordingly, patients with extreme Lp(a) levels, above the 99th percentile (400 nmol/l; 200 mg/dl) should be considered as high CV risk patients per se, even in the absence of other risk factors and, consequently, candidates for considering lowering LDL-C to less than 70 mg/dl.100,102

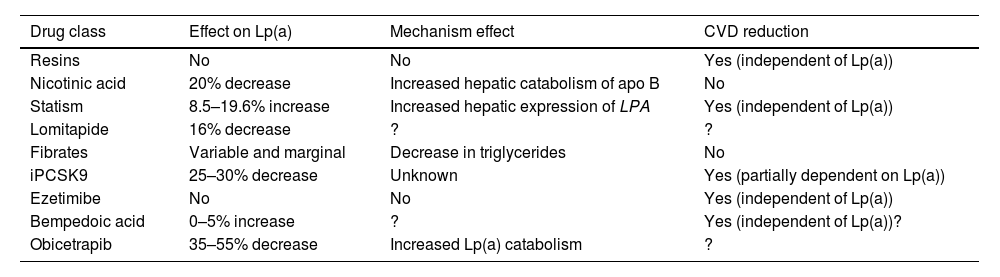

Targets and treatment strategies to lower Lp(a) valuesCurrent drug approachAt present there is no pharmacological treatment that has been approved to specifically reduce elevated plasma Lp(a) concentrations, and if the expected benefits based on observational evidence are confirmed in ongoing interventional studies, this will be a clinical imperative and one of the greatest challenges in the prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis. Current lipid-lowering drugs have a neutral or clinically insignificant effect on Lp(a) concentrations (Table 4). That being said, in recent years, there is hope for the management of elevated Lp(a) levels with new therapies, some of which are in the final stages of development.

Drugs commercially available and their relationship to Lp(a) concentrations.

| Drug class | Effect on Lp(a) | Mechanism effect | CVD reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resins | No | No | Yes (independent of Lp(a)) |

| Nicotinic acid | 20% decrease | Increased hepatic catabolism of apo B | No |

| Statism | 8.5–19.6% increase | Increased hepatic expression of LPA | Yes (independent of Lp(a)) |

| Lomitapide | 16% decrease | ? | ? |

| Fibrates | Variable and marginal | Decrease in triglycerides | No |

| iPCSK9 | 25–30% decrease | Unknown | Yes (partially dependent on Lp(a)) |

| Ezetimibe | No | No | Yes (independent of Lp(a)) |

| Bempedoic acid | 0–5% increase | ? | Yes (independent of Lp(a))? |

| Obicetrapib | 35–55% decrease | Increased Lp(a) catabolism | ? |

apo B: apolipoprotein B; CVD: cardiovascular disease; Lp(a): lipoprotein (a); PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9;? : doubtful.

In contrast to other lipoprotein particles, such as c-LDL or triglyceride levels, plasma Lp(a) concentrations do not change in any clinically relevant way as a result of changes in diet and healthy lifestyle.121 The effect of current lipid lowering agents on Lp(a) concentration is summarised in Table 4. While some of these drugs decrease Lp(a) levels to a significant extent, there are no data concerning the possible CV benefit mediated by this reduction.

Resins have not proven that they modify Lp(a)122 levels. Niacin induces a reduction in Lp(a) levels by approximately 20%.123,124 Previous studies have suggested that treatment with statins may increase Lp(a) levels in percentage terms. In this context, a recent meta-analysis, including 39 studies and 24,448 participants, has illustrated that statin treatment failed to alter the CVD risk associated with a slight increase in Lp(a) levels, making such a change clinically irrelevant.125 Given that the protective effect of LDL cholesterol-lowering therapy is proportional to baseline CV risk, the inclusion of Lp(a) in the risk estimation could identify patients with greater potential benefit by virtue of their higher absolute risk. This fact provides support for the notion that patients with moderate or borderline CV risk and elevated Lp(a) levels (>50 mg/dl) should have their risk recalculated and be considered for initiation of lipid-lowering therapy, starting with statins104 and considering treatment intensification for individuals at high or very high risk. In other words, elevated Lp(a) may warrant more ambitious c-LDL control targets. Lomitapide, whose sole indication at present is homozygous FH, reduces Lp(a) levels in subjects with hypercholesterolaemia.126,127 The effect of fibrates is highly variable and is dependent on baseline triglyceride concentrations.14 In a meta-analysis of seven trials of ezetimibe in monotherapy, ezetimibe significantly decreased Lp(a) levels by 7.1%.128 In contrast, in another meta-analysis, ezetimibe, whether in monotherapy versus placebo or in combination with a statin versus a statin alone, did not significantly modify Lp(a) concentrations.129 More recently, in a phase 2 trial, bempedoic acid did not significantly reduce Lp(a) levels.130,131 Similarly, the combination of bempedoic acid with evolocumab was not superior to evolocumab monotherapy in terms of Lp(a) variation relative to baseline.132 In short, these lipid-lowering drugs are not suitable tools for reducing elevated Lp(a) levels, either because they lack efficacy or relevant clinical benefit, or because of the side effects of some of these molecules.133

iPCSK9 (evolocumab and alirocumab) have exhibited a pronounced effect on Lp(a) levels with a mean reduction of 26.7% (95% CI: −29.5 to −23.9%) with significant heterogeneity in relation to comparator and duration of treatment.134

Subgroup analyses from the Odyssey and Fourier studies have revealed a greater absolute benefit in terms of CV event reduction in patients with elevated Lp(a) following treatment with alirocumab and evolocumab, respectively. While some of the benefit may be attributable to the higher absolute risk in patients with elevated Lp(a), post hoc analyses suggest the possibility of an additional benefit linked to the decrease in Lp(a) in and of itself, independent of the effect on c-LDL. The design of the studies and the post hoc type of these analyses preclude drawing any definitive conclusion in this regard.135,136

Inclisiran, a small interfering RNA (pRNAi) that targets intracellular PCSK9, has been proven to lower Lp(a) levels by approximately 20%.137 The clinical benefit of this finding is currently unknown, although it could be hypothesised to be similar to that of iPCSK9. Finally, Obicetrapib, a selective cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitor in clinical development, has been shown to reduce Lp(a) by 33.8% and 56.5% at doses of 5 and 10 mg, respectively.138

The failures in some clinical trials of drugs presumed to have a favourable effect on CVD through improvements in the atherogenic lipid profile (including Lp(a) reduction) with niacin and with CETP inhibitors, dictate the need for prudence prior to assuming CV benefits from Lp(a)-lowering drugs until adequate clinical trials have been developed that specifically assess relevant clinical endpoints, not simply lipid profile ‘improvements’.

ApheresisUntil now, the most effective intervention to reduce Lp(a) concentrations is lipoprotein apheresis.139 The efficacy of this procedure is striking, achieving a 70–80% reduction in Lp(a) levels, although they subsequently increase to reach an average reduction of Lp(a) concentrations in the range of 25–40%, depending on the course and baseline Lp(a) levels.139

A single-blind, randomised, crossover study conducted in 20 participants with refractory angina and elevated Lp(a) undergoing lipoprotein apheresis for three months indicates that this intervention may enhance myocardial perfusion and improve angina control.140

An RCT entitled MultiSELECt is currently underway that compares weekly Lp(a) apheresis with maximally tolerated lipid-lowering therapy in approximately 1,000 individuals aged 18–70 years with Lp(a) > 120 nmol/l or higher, c-LDL < 100 mg/dl, and CVD. The ultimate goal is to explore the clinical benefit of Lp(a) apheresis on MACE.120

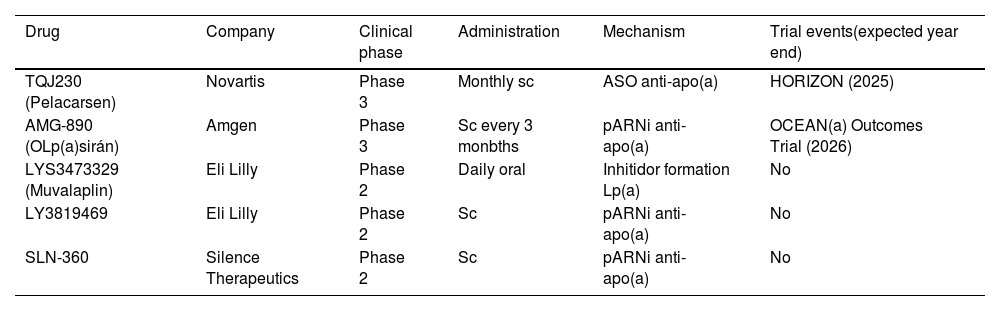

New therapies in the pipelineA completely different approach to reducing abundant proteins involves preventing them from being produced by inhibiting the translation of their mRNA. The main two classes of RNA-targeting drugs developed for this purpose are single-stranded antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and pARNI (Table 5). Both strategies share a similar mechanism of action: after parenteral administration and introduction into the hepatocyte, they bind to a specific sequence of the mRNA of interest, at the nuclear level for ASOs and in the cytoplasm in the case of pARNi. This interaction results in the degradation of the target mRNA and, as a consequence, decreased translation of the encoded protein. One of the main advantages of RNA-based drugs is the possibility of being highly specific in targeting proteins with high plasma concentrations such as apo(a), a component of the Lp(a) particle.141 Pelacarsen is a 20-nucleotide synthetic ASO, conjugated to GalNAc3 that targets apo(a) mRNA, which has been proven to be up to 80% effective in phase 1 and 2 trials.141,142 The impact of 80 mg monthly Pelacarsen on lowering MACE is being evaluated in the HORIZON trial (NCT04023552), a Phase 3 RCT that has enrolled more than 7,000 patients with CVD and Lp(a) > 70 mg/dl, to compare efficacy and safety. Results are expected in 2025.143 OLp(a)siran is a pRNAi that halts apo(a) production by degrading apo(a) messenger RNA, preventing the assembly of Lp(a) in the hepatocyte. In preclinical development, it has been shown to decrease Lp(a) by up to 98% in individuals with levels >70 nmol/l without serious adverse events.144 In a phase 2 RCT, OCEAN(a) DOSE (OLp(a)siran Trials of CVD Events and LipoproteiN(a) Reduction) 281 subjects with CVD and Lp(a) >150 nmol/l assigned to receive OLp(a)siran (10 mg/every 12 weeks, 75 mg/every 12 weeks, 225 mg/every 12 weeks, or 225 mg/every 24 weeks) attained significant reductions in Lp(a) levels (70.5, 97.4, 101.1, and 100.5%, respectively).145 The Phase 3 RCT, OLp(a)siran Trials of CVD Events and Lipoprotein(a) Reduction (OCEAN(a)) - Outcomes Trial (NCT05581303)146 is now actively recruiting participants. Another pRNAi, SLN360 aimed at blocking apo(a), has been reported to have obtained reductions of between 46% and 98% with therapy administered subcutaneously at a single dose of: 30, 100, 300, or 600 mg in subjects with Lp(a) > 150 nmol/l.147 SLN360 is also the subject of another ongoing Phase 2 RCT (Study to Investigate the Safety, Tolerability, PK, and PD Response of SLN360 in Subjects with Elevated Lipoprotein(a); NCT04606602) pending disclosure of results.148 In the ALP(A)CA study, the primary objective is to determine the efficacy and safety of LY3819469 in adults with elevated Lp(a).149 Finally, Eli Lilly has a small molecule for daily oral administration (LYS3473329 (Muvalaplin)), which inhibits Lp(a) formation, and that is exhibiting promising results. Future directions with oral therapies and even gene-editing treatments with nanoparticles capable of modulating Lp(a) transcription and translation are the first step towards definitive control of residual CV risk favoured by this Lp.150 All of this is summarised in Table 5.

Lp(a)-lowering study drugs.

| Drug | Company | Clinical phase | Administration | Mechanism | Trial events(expected year end) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TQJ230 (Pelacarsen) | Novartis | Phase 3 | Monthly sc | ASO anti-apo(a) | HORIZON (2025) |

| AMG-890 (OLp(a)sirán) | Amgen | Phase 3 | Sc every 3 monbths | pARNi anti-apo(a) | OCEAN(a) Outcomes Trial (2026) |

| LYS3473329 (Muvalaplin) | Eli Lilly | Phase 2 | Daily oral | Inhitidor formation Lp(a) | No |

| LY3819469 | Eli Lilly | Phase 2 | Sc | pARNi anti-apo(a) | No |

| SLN-360 | Silence Therapeutics | Phase 2 | Sc | pARNi anti-apo(a) | No |

apo (a): lipoprotein (a); ASO: anti-sense oligonucleotides; Lp(a): lipoprotein (a); sRNAi: small interfering double-stranded RNA; Sc: subcutaneous.

Other clinical trials of interest currently in progress are presented in the Supplementary material, Appendix A, Table S3.