Adults with diabetes have been identified as being at risk of severe forms of COVID-19.1 Pregnant women may be at increased risk of infection during travel to healthcare facilities for screening and/or a diagnosis of gestational hyperglycemia (GH), as well as for the monitoring of GH or pregestational diabetes (PGD). The Spanish Diabetes and Pregnancy Group (Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo [GEDE]) has decided to join other medical bodies2–5 in establishing specific recommendations for these two populations, based on the current scientific evidence and for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to minimize risks.

In both of these groups of pregnant women we advise the use of personal protection measures when travelling, including a mask6–8 and gloves, adequate hand hygiene, and the maintenance of a safety distance of 2m9,10 between people, in other words, the same measures also being recommended for the rest of the population (Fig. 1).

Pregestational diabetesPatients in preconception care clinics are advised to use a safe contraceptive method at least until the acute phase of the pandemic is over.

It is advisable to establish and maintain regular remote communication, either by telephone or e-mail, with both the obstetric and the endocrinological teams to allow for an adequate care and follow-up plan.

In general, efforts should be made to conduct visits with the endocrinologist/educator on a remote basis. Most in-person visits should coincide with the visits made to the Obstetrics Department. However, more in-person visits may be required depending on the individual situation of each pregnant woman, particularly at the start of pregnancy, if preconception control has not been followed.

During this period, it is important for patients to:

- •

Have access to the material needed for monitoring, thus facilitating optimum glycemic control: needles, blood glucose and ketonemia/ketonuria test strips, consumables for infusion and continuous glucose monitoring (FreeStyle Libre).

- •

Have access to glucometers, insulin calculators, infusion kits, real time glucose monitoring (RT-CGM) and Flash systems. Such access should be made every 14–21 days according to control.

- •

Have access to the medication they need, such as folic acid, iodine, insulin or aspirin.

- •

Record body weight and blood pressure.

- •

Have access to online educational material (to be prepared).

- •

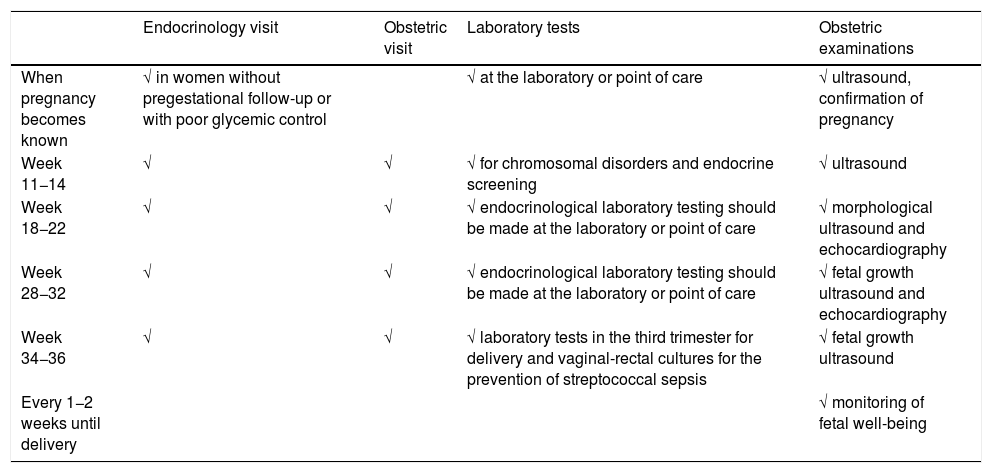

Table 1 shows the proposed in-person follow-up schedule (endocrine and obstetric).

Table 1.Proposed follow-up schedule for pregnant women with pregestational diabetes, modified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Endocrinology visit Obstetric visit Laboratory tests Obstetric examinations When pregnancy becomes known √ in women without pregestational follow-up or with poor glycemic control √ at the laboratory or point of care √ ultrasound, confirmation of pregnancy Week 11−14 √ √ √ for chromosomal disorders and endocrine screening √ ultrasound Week 18−22 √ √ √ endocrinological laboratory testing should be made at the laboratory or point of care √ morphological ultrasound and echocardiography Week 28−32 √ √ √ endocrinological laboratory testing should be made at the laboratory or point of care √ fetal growth ultrasound and echocardiography Week 34−36 √ √ √ laboratory tests in the third trimester for delivery and vaginal-rectal cultures for the prevention of streptococcal sepsis √ fetal growth ultrasound Every 1−2 weeks until delivery √ monitoring of fetal well-being - •

Visit once pregnancy becomes known in pregnant women without pregestational follow-up and/or poor metabolic control.

- •

Visit in weeks 11 and 14, coinciding with fetal ultrasound and laboratory tests.

- •

Visit in week 18−22, coinciding with fetal morphological ultrasound and echocardiography. Laboratory or point of care testing should also be made.

- •

Visit in week 28−32, coinciding with fetal growth ultrasound and echocardiography. Laboratory or point of care testing should also be made.

- •

Visit in week 34−36, coinciding with fetal growth ultrasound, vaginal-rectal culture for the prevention of sepsis due to streptococcus in the newborn infant, and laboratory tests corresponding to the third trimester for delivery.

- •

Conduct the monitoring of fetal well-being, until delivery, every 1−2 weeks, according to availability at each center, and metabolic control of the patient. Both follow-up and the end of pregnancy should be individualized according to each pregnant woman and the situation of the center, though the recommendations of the latest GEDE guide should also be observed, if possible.11

Daily physical exercise at home, despite confinement, is recommended (https://www.embactivo.es/).

Ocular fundus assessment in the short term should only be requested in those patients with retinal alterations prior to pregnancy, while in the remaining cases it should be postponed and made on a subsequent visit.

The algorithm for PCR and/or rapid test detection of COVID-19 should be defined at each center according to the available resources, based on the technical document of the Spanish Ministry of Health referring to COVID-19 and pregnancy.12

Gestational hyperglycemiaDiagnosis of gestational hyperglycemiaThe first recommendation is to maintain the two-stage diagnostic protocol proposed in the Diabetes and Pregnancy guide of the GEDE,11 provided that the conditions of the pregnant woman and her environment and the work burden of the laboratory allow it, and that the professionals involved in the follow-up of these women can take charge of the new diagnoses, and finally that the safety conditions of the pregnant woman are guaranteed (waiting room with safety distance, mask, hand washing, and preferred use of private vehicle to visit the center).

If this is not possible, alternative tests should be made available for the duration of this exceptional situation. The use of alternative tests means taking the following considerations into account2:

- •

The tests must be feasible in settings with limited resources, and should minimize contact with the healthcare center.

- •

The tests must have a high specificity (few false-positive results) even if their sensitivity is limited. Screening tests have high sensitivity (few false-negative results) but low specificity (many false positive results), and therefore could saturate the healthcare services.

- •

Complementary safety networks are needed to minimize missed diagnoses, particularly in women at higher risk. Thus, for example, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) considers recording HbA1c+plasma glucose levels in both the first trimester and at 24–28 weeks, among other measures.2

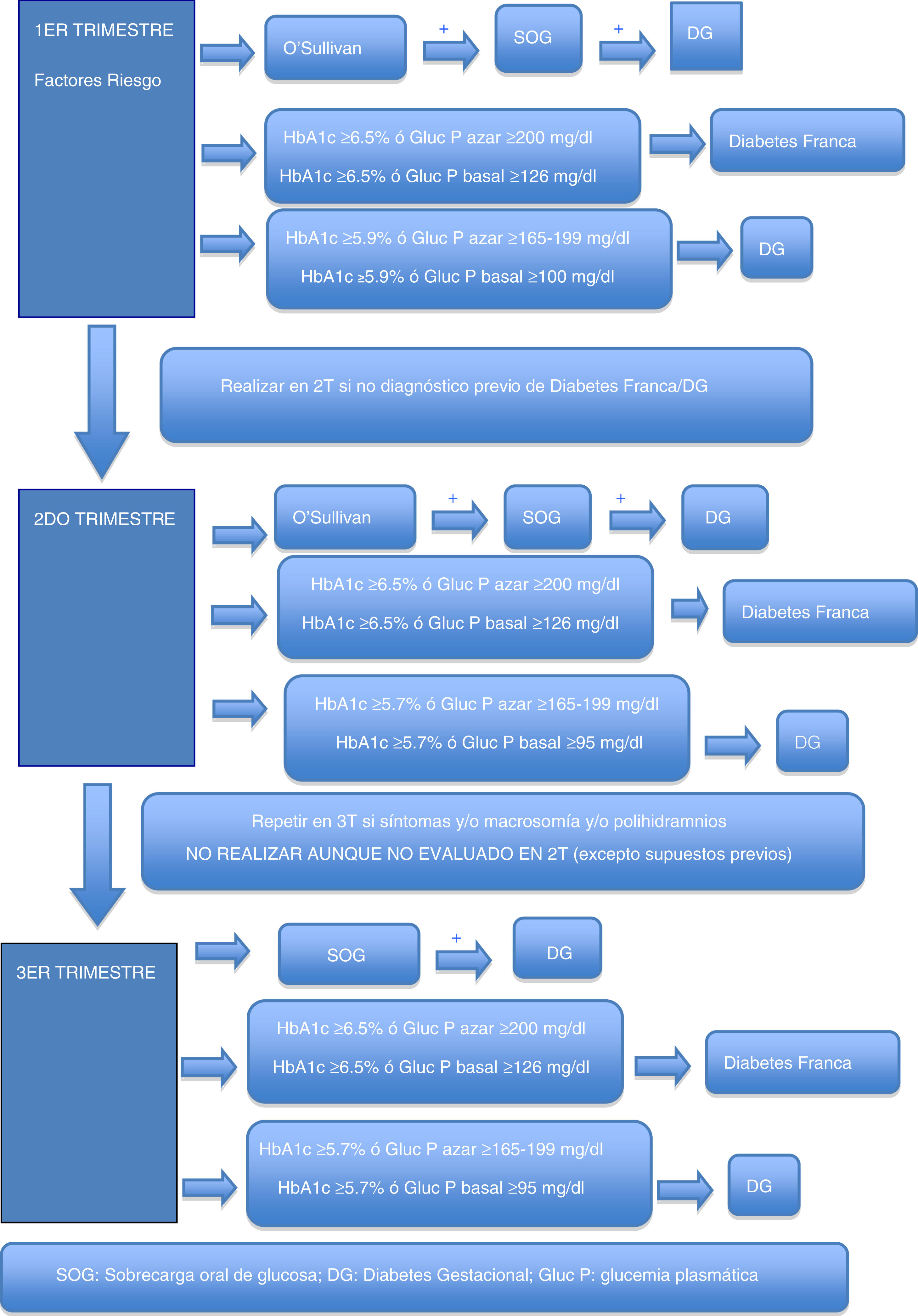

During the first trimester, screening for gestational hyperglycemia should continue in pregnant women at risk.11 The primary aim of such screening is to detect pregnant women with frank diabetes and those with early gestational diabetes (GD), who have a risk of complications of pregnancy equal to or greater than that of women with pregestational type 2 diabetes.

In cases where the regular screening test (O’Sullivan test) is not possible, the options are the measurement of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), basal plasma glucose or plasma glucose at random (to make laboratory testing coincide with the obstetric visit, for example, and to avoid a second visit to the laboratory in order to perform an oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT]). Some groups recommend that all patients with previous GD should be treated as GD without laboratory testing.5

These criteria are established based on the scientific evidence obtained from previous studies and on recommendations from other medical bodies which possess data indicating that the probability of detecting cases of more severe GD with poorer perinatal outcomes is greater when these cut-off points are used. It should be assumed that probably not all cases of GD will be detected through such screening, particularly the mildest presentations, but we will indeed detect those with an impact upon perinatal morbidity and mortality, which is what is needed at this exceptional time.

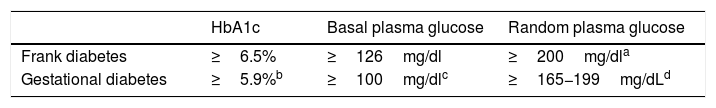

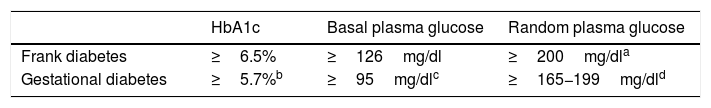

Table 2 shows the cut-off points established for frank diabetes and proposed for GD.

Options for the diagnosis of frank diabetes and gestational diabetes in the first trimester.

| HbA1c | Basal plasma glucose | Random plasma glucose | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frank diabetes | ≥6.5% | ≥126mg/dl | ≥200mg/dla |

| Gestational diabetes | ≥5.9%b | ≥100mg/dlc | ≥165−199mg/dLd |

Concordant criterion among the different guidelines as risk identifier in the first trimester2–5. In our setting, in a study conducted at Hospital del Mar in Barcelona in a multiethnic population, HbA1c≥5.9% in the first trimester was found in 3.9% of the population and was associated with fetal macrosomia and pre-eclampsia, regardless of the presence of GD13. Applying the same criterion to the subgroup of pregnant women at risk, a higher percentage is expected to be identified in the study group, though the figure will be lower in the general obstetric population.

Blood glucose ≥100mg/dl identifies ≃ 2% of the population and is associated with an increased risk of caesarean delivery and of a newborn large for gestational age/macrosomia, independently of the diagnosis of GD14.

The recommendation of the GEDE for the diagnosis of gestational hyperglycemia in the first trimester, when the standard protocol cannot be applied, is to measure HbA1c combined with plasma glucose concentration (preferably at random due to its greater feasibility, or alternatively basal glucose).

Screening using HbA1c and blood glucose at random allows us to obviate the blood glucose curve, does not require the pregnant woman to be under fasting conditions, and can be performed on the same day as obstetric monitoring.

Plasma glucose seeks to detect women with recent-onset hyperglycemia and/or hemoglobin disorders.

Plasma glucose measurements for diagnostic purposes should take into account measures to minimize anaerobic glycolysis.

Second trimesterFor pregnant women not previously diagnosed with diabetes, universal screening is proposed at around week 28 of pregnancy (obstetric visit between weeks 28 and 32 of pregnancy).

As in the first trimester, the first recommendation is to maintain the two-phase diagnostic protocol at those centers where this is possible. In the current pandemic situation, a screening test result of ≥200mg/dl may be considered as diagnostic of GD. Outside the pandemic, this is not done, because an O’Sullivan test result of ≥200mg/dl has a positive predictive value for GD according to National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) criteria ranging from 34 to 100%15 (59.9% in our setting16).

Possible alternatives for centers that are unable to diagnose in two stages are the determination of HbA1c, basal plasma glucose or random plasma glucose. Table 3 describes the cut-off points. Again, these cut-off points have been established based on the available scientific evidence in order to select patients with gestational hyperglycemia at greater risk of suffering perinatal complications2–4.

Options for the diagnosis of gestational hyperglycemia in the second trimester.

| HbA1c | Basal plasma glucose | Random plasma glucose | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frank diabetes | ≥6.5% | ≥126mg/dl | ≥200mg/dla |

| Gestational diabetes | ≥5.7%b | ≥95mg/dlc | ≥165−199mg/dld |

Basal blood glucose ≥95mg/dl corresponds to the IADPSG cut-off point for an odds ratio (OR) of 2.0 of the HAPO population, in which this cut-off point identified a prevalence of ≃4%21. At centers using IADPSG diagnostic criteria, the screening/diagnostic procedure may be limited to basal blood glucose (≥92mg/dl, OR 1.75), since it yields a very high percentage of the diagnoses made with the complete curve. In the HAPO cohort, this cut-off point identified a prevalence of ≃ 8%19. In our setting, the prevalence in the San Carlos trial based on basal blood glucose was>15%20.

Proposed by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists2. In a meta-analysis of studies using different diagnostic criteria for GD, HbA1c≥5.7% had a mean sensitivity of 24.7% and a specificity of 95.5% for the diagnosis of GD17. With regard to the NDDG criteria, Maesa et al. reported a sensitivity of 25.9% for a cut-off point of ≥5.5%18. This is why guides such as the Canadian guide propose a combined strategy of HbA1c and random glycemia, while the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists propose HbA1c and basal glycemia or random glycemia2. The GEDE also proposes this combined strategy, with an HbA1c cut-off point of 5.7%, which is that used by the other international bodies.

Some groups also recommend that patients with previous GD should be treated as GD without laboratory testing3, even though this approach may include a very few patients who do not have GD. The diagnostic test is obviated, thereby minimizing the risk of COVID-19 contagion, and these are women whose need for therapeutic education is low.

The recommendation of the GEDE for the diagnosis of gestational hyperglycemia in the second trimester, when the standard protocol cannot be applied, is to measure HbA1c combined with plasma glucose concentration (preferably at random due to its greater feasibility, or alternatively basal glucose).

Screening using HbA1c and blood glucose at random allows us to obviate the blood glucose curve, does not require the pregnant woman to be under fasting conditions, and can be performed on the same day as obstetric monitoring.

Plasma glucose seeks to detect women with recent-onset hyperglycemia and/or hemoglobin disorders.

Plasma glucose measurements for diagnostic purposes should take into account measures to minimize anaerobic glycolysis.

In addition, during pregnancy in any patient with severe glycosuria, clinically suspected diabetes or a fetus large for the gestational age / polyhydramnios evidenced by ultrasound, GD should be ruled out with any of the previously described options. In the absence of these circumstances, screening in the third trimester of pregnancy should not be considered, even if screening has not been performed in the second trimester.

TreatmentThe treatment and follow-up of GD should be maintained at the usual centers with Endocrinology/Primary Care visits and obstetric visits. After the therapeutic education period (in-person and/or remote), combined in-person visits should be organized similar to those described for women with PGD.

Insulin is the drug of choice when good control criteria are not met and pharmacological treatment is needed. However, when starting insulin is not feasible, metformin initially may be considered for delaying or avoiding it22,23.

Daily physical exercise at home, despite confinement, is recommended (https://www.embactiva.es/).

Both follow-up and the end of pregnancy should be individualized according to each pregnant woman and the situation of the center, while the recommendations established by the latest GEDE guide are observed, if possible11.

The algorithm for PCR and/or rapid test detection of COVID-19 should be defined at each center according to the available resources, based on the technical document of the Spanish Ministry of Health referring to COVID-19 and pregnancy12.

PostpartumBreastfeeding is recommended in all pregnant women with PGD or GD, including COVID-19 positive women; in these cases, contact between the mother and the newborn infant should be maintained and breastfeeding performed with breathing isolation measures24.

Puerperal women with PGD should be monitored online for the adjustment of metabolic control. Obstetric visits should be kept to the essential minimum required for the assessment of adequate postpartum in these patients, with online visits being resorted to as much as possible.

As regards postpartum, in those patients diagnosed with GD, monitoring should be postponed until the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, care being taken not to exceed the first year of the postpartum period. Patients diagnosed with frank diabetes or with suspected type 1 diabetes may be advised to maintain lifestyle measures, together with fasting capillary blood glucose testing, for example every 1−2 weeks, to detect alarm patterns.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acosta Delgado, Domingo. Hospital U. Virgen del Rocío - Seville

Ballesteros Pérez, Mónica. Hospital U. Joan XXIII - Tarragona

Bandres Nivela, María Orosia. Hospital Royo Villanova - Zaragoza

Bartha Rasero, José Luis. Hospital U. La Paz - Madrid

Bellart Alfonso, Jordi. Hospital Clínico - Barcelona

Blanco Carnero, José Eliseo. Hospital Clínico U. Virgen de la Arrixaca - Murcia

Botana López, Manuel. Hospital Lucus Augusti - Lugo

Bugatto González, Fernando. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cádiz

Codina Marcet, Mercedes. Hospital Son Espases - Palma de Mallorca

Corcoy Pla, Rosa. Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau - Barcelona

Cortazar Galarzar, Alicia. Hospital de Cruces - Baracaldo - Vizcaya

Donnay Candil, Sergio. Hospital U. Fundación Alcorcón - Madrid

Durán Rodríguez-Hervada, Alejandra. Hospital U. Clínico San Carlos - Madrid

Gómez García, María del Carmen. C.S. Velez-Norte – Málaga

González González, Nieves Luisa. Universidad de La Laguna. Tenerife. Hospital Universitario de Canarias.

Goya Canino, María M. Hospital U. Vall d’ Hebrón - Barcelona

Herranz de la Morena, Lucrecia. Hospital U. La Paz - Madrid

López Tinoco, Cristina. Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cádiz

Martín García, Patricia. Hospital U. Fundación Alcorcón - Madrid

Megía Colet, Ana. Hospital U. Joan XXIII – Tarragona

Montañes Quero, María Dolores. Hospital 12 de Octubre - Madrid

Moreno Reina, Eduardo. Hospital U. Virgen del Rocío - Seville

Mozas Moreno, Juan. Hospital Materno Virgen de las Nieves – Granada

Ontañón Nasarre, Marta. Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias - Alcalá de Henares - Madrid

Perea Castilla, Verónica. Hospital Universitari Mutua Terrassa - Barcelona

Picón César, María José. Hospital U. Virgen de la Victoria - Malaga

Rubio García, José Antonio. Hospital U. Príncipe de Asturias - Alcalá de Henares - Madrid

Soldevila Madorell, Berta. Hospital German Trias i Pujol. Badalana - Barcelona

Vega Guedes, Begoña. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno-Infantil, Las Palmas - Las Palmas

Vinagre Torres, Irene. Hospital Clínico y Provincial de Barcelona - Barcelona

Wägner Falhin, Ana María. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno-Infantil, Las Palmas - Las Palmas