Primary hyperaldosteronism (PH) is the most common cause of secondary hypertension (HTN) and is associated with a higher cardiometabolic risk than essential HTN. Nevertheless, PH remains clearly underdiagnosed. An early diagnosis and adequate treatment of this disease are essential to reduce the cardiometabolic morbimortality associated with aldosterone excess. PH follow-up is equally essential; however, there is little consensus on how it should be performed, being a topic rarely mentioned by the different clinical practice guidelines. The aim of this executive summary is to summarize the recommendations made in the Spanish consensus of PH for the diagnosis, management, and follow-up of these patients. The Spanish consensus was reached from a multidisciplinary perspective through a nominal group consensus approach by experts from the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition (SEEN), the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC), the Spanish Society of Nephrology (SEN), the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI), the Spanish Society of Radiology (SERAM), the Spanish Society of Vascular and Interventional Radiology (SERVEI), the Spanish Society of Laboratory Medicine (SEQC(ML)), the Spanish Society of Anatomic-Pathology (EAP), and the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC).

El hiperaldosteronismo primario (HAP) es la causa más frecuente de hipertensión arterial (HTA) secundaria, y se asocia con un mayor riesgo cardio metabólico que la HTA esencial. Sin embargo, el HAP todavía se encuentra claramente infradiagnosticado. Un diagnóstico precoz y un tratamiento adecuado de esta enfermedad son fundamentales para reducir la morbimortalidad cardiometabólica asociada al exceso de aldosterona. El seguimiento del HAP también es un punto importante, sin embargo, existe poco consenso sobre cómo se debe realizar, siendo un tema apenas mencionado en las diferentes guías clínicas. El objetivo de este resumen ejecutivo es resumir las recomendaciones aportadas en el consenso español de HAP en relación con el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y el seguimiento de estos pacientes. El consenso español se elaboró desde una perspectiva multidisciplinar, en un enfoque de consenso de grupo nominal por expertos de la Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición (SEEN), de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología (SEC), de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología (SEN), de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna (SEMI), de la Sociedad Española de Radiología (SERAM), de la Sociedad Española de Radiología Vascular e Intervencionista (SERVEI), de la Sociedad Española de Medicina de Laboratorio (SEQC(ML), de la Sociedad Española de Anatomía Patológica (EAP) y de la Asociación Española de Cirujanos (AEC).

Primary hyperaldosteronism (PH) is a common and curable cause of secondary hypertension (HTN), reaching prevalences of 5% up to 10% in the overall hypertensive population and up to 30% in patients with severe and resistant HTN.1–4 It is widely known that individuals with PH exhibit an increased incidence of cardiovascular events and mortality vs. cases with essential HTN matched by age, gender, and blood pressure (BP) levels.5–12

Targeted pharmacological therapies are available to block the deleterious effects of aldosterone excess, being effective in controlling BP and reducing associated cardiovascular risk. In addition, approximately 40% up to 50% of PH cases are unilateral and may be potentially cured by adrenalectomy.5,11,13 Using the Primary Aldosteronism Outcome (PASO) group criteria is advised to define the control objectives of biochemical and clinical response to surgical treatment, although, to date, there is no consensus on how to evaluate medical treatment outcomes.14

In this article, we summarize the current available evidence on the diagnosis, management, and follow-up of PH, based on our previous Spanish multidisciplinary clinical practice guidelines. The complete documents for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up have already been published in a different journal.15,16

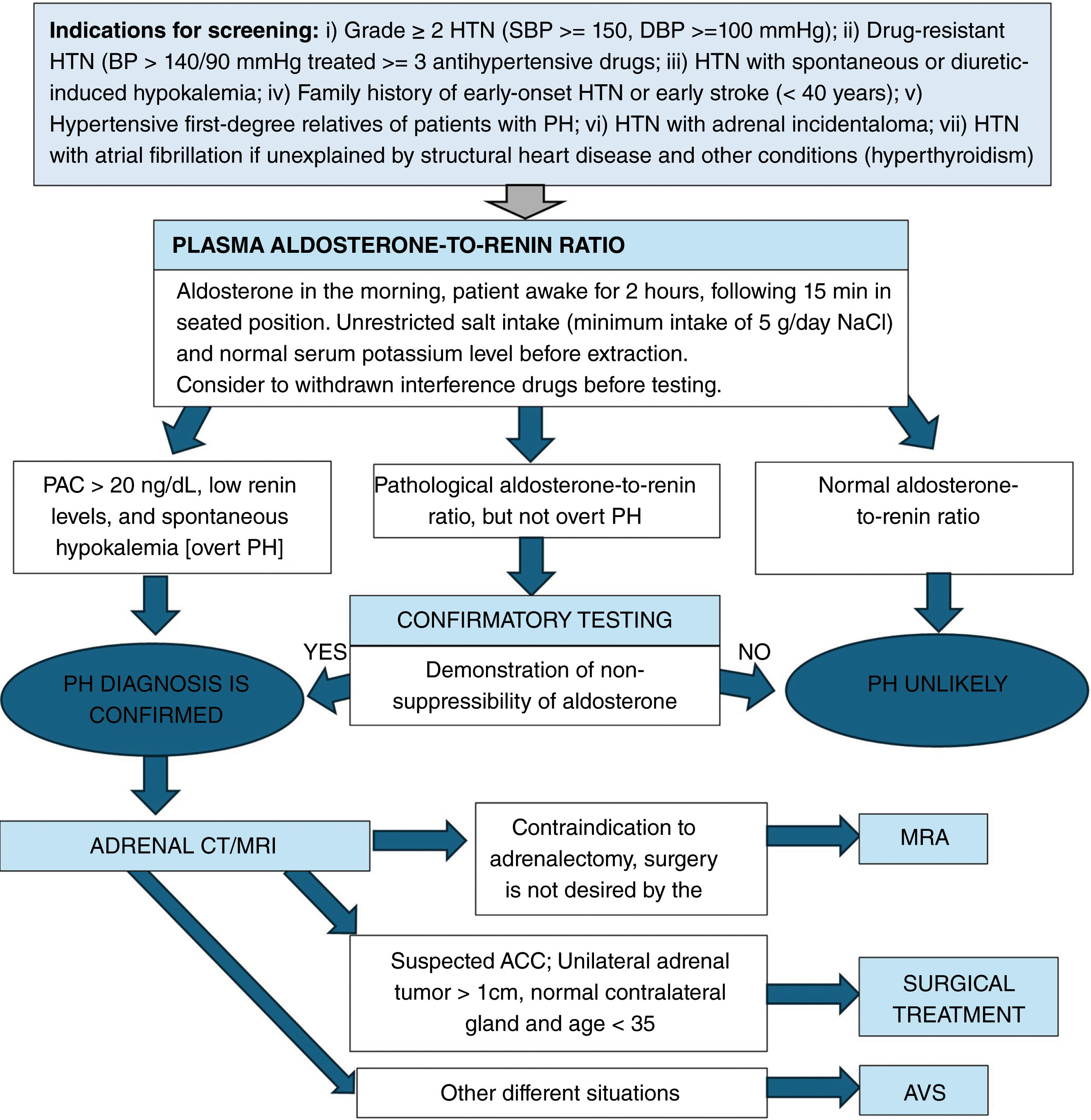

DiagnosisThe diagnosis of PH is usually a multistep approach: (1) case detection; (2) case confirmation, (if required); and (3) subtype differentiation (Fig. 1).

Diagnosis of primary hyperaldosteronism. HTN, hypertension; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BP, blood pressure; PH, primary hyperaldosteronism; PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration; AVS, adrenal venous sampling; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; ACC, adrenocortical carcinoma.

- -

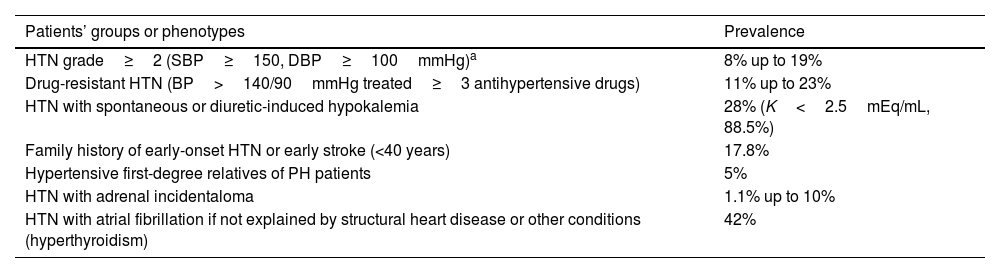

Indication for screening: PH screening is advised based on the patient's phenotype and the associated prevalence of PH17–20 (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1.Indications for PH screening and prevalence in these settings.

Patients’ groups or phenotypes Prevalence HTN grade≥2 (SBP≥150, DBP≥100mmHg)a 8% up to 19% Drug-resistant HTN (BP>140/90mmHg treated≥3 antihypertensive drugs) 11% up to 23% HTN with spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalemia 28% (K<2.5mEq/mL, 88.5%) Family history of early-onset HTN or early stroke (<40 years) 17.8% Hypertensive first-degree relatives of PH patients 5% HTN with adrenal incidentaloma 1.1% up to 10% HTN with atrial fibrillation if not explained by structural heart disease or other conditions (hyperthyroidism) 42% HTN, hypertension; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BP, blood pressure; PH, primary hyperaldosteronism.

- -

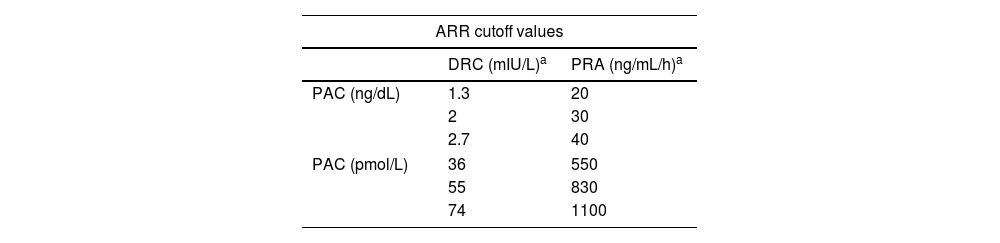

Interpretation: The most sensitive PH screening test is the plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC)-to-renin ratio (plasma renin activity (PRA) or direct plasma renin concentration (DRC)20,22,23). However, there is disagreement surrounding the cutoff value that should be used for this purpose (Table 2). On considering a minimum PAC to interpret the aldosterone-to-renin ratio (ARR), overall, in the presence of a slightly elevated PAC, e.g. >10ng/dL, along with suppressed renin, PH should be suspected. PACs measured using CLEIA are lower than when measured using RIA. DRC is significantly higher than PRA, and levels are more elevated than when measured using IRMA. Anyway, cutoff values of PAC and DRC should be adapted based on the methodology used especially if these are different.

Table 2.Criteria of biochemical screening for primary hyperaldosteronism.

ARR cutoff values DRC (mIU/L)a PRA (ng/mL/h)a PAC (ng/dL) 1.3 20 2 30 2.7 40 PAC (pmol/L) 36 550 55 830 74 1100 ARR, aldosterone–renin-ratio; DRC, direct plasma renin concentration; PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration; PRA, plasma renin activity.

Adapted from Mulatero, P. et al.18 - -

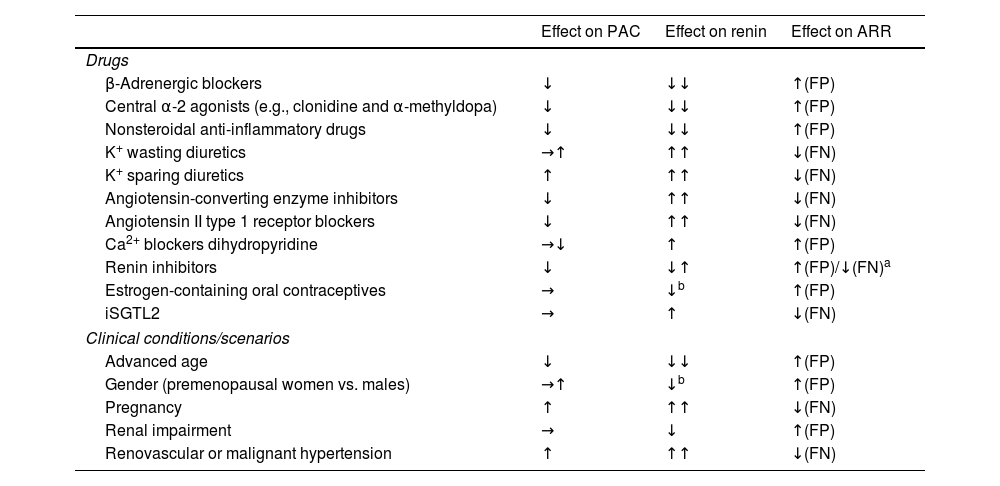

Testing conditions: Multiple antihypertensive drugs (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor [ACEIs], angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], b-adrenergic blockers, diuretics including mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), and epithelial sodium channel [ENaC] inhibitors) interact with the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone axis.13 Therefore, when safely possible, these antihypertensive drugs should be discontinued for, at least, 2–4 weeks before being evaluated. In addition, several non-pharmacological conditions may interfere with the ARR (Table 3). The serum sodium and potassium status also affect the ARR results; for example, hypokalemia and sodium restriction trigger false negatives, while potassium and sodium loading may trigger false positives.13

Table 3.Conditions and drugs affecting PAC, renin, and ARR.

Effect on PAC Effect on renin Effect on ARR Drugs β-Adrenergic blockers ↓ ↓↓ ↑(FP) Central α-2 agonists (e.g., clonidine and α-methyldopa) ↓ ↓↓ ↑(FP) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs ↓ ↓↓ ↑(FP) K+ wasting diuretics →↑ ↑↑ ↓(FN) K+ sparing diuretics ↑ ↑↑ ↓(FN) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors ↓ ↑↑ ↓(FN) Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers ↓ ↑↑ ↓(FN) Ca2+ blockers dihydropyridine →↓ ↑ ↑(FP) Renin inhibitors ↓ ↓↑ ↑(FP)/↓(FN)a Estrogen-containing oral contraceptives → ↓b ↑(FP) iSGTL2 → ↑ ↓(FN) Clinical conditions/scenarios Advanced age ↓ ↓↓ ↑(FP) Gender (premenopausal women vs. males) →↑ ↓b ↑(FP) Pregnancy ↑ ↑↑ ↓(FN) Renal impairment → ↓ ↑(FP) Renovascular or malignant hypertension ↑ ↑↑ ↓(FN) PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration; ARR, aldosterone–renin-ratio; FP, false positive; FN, false negative.

Adapted from: Funder JW. et al.23

However, in patients with resistant HTN or high cardiovascular risk, discontinuing antihypertensive treatment may not be feasible. In these cases, ARR should be interpreted along with the interfering drugs.24

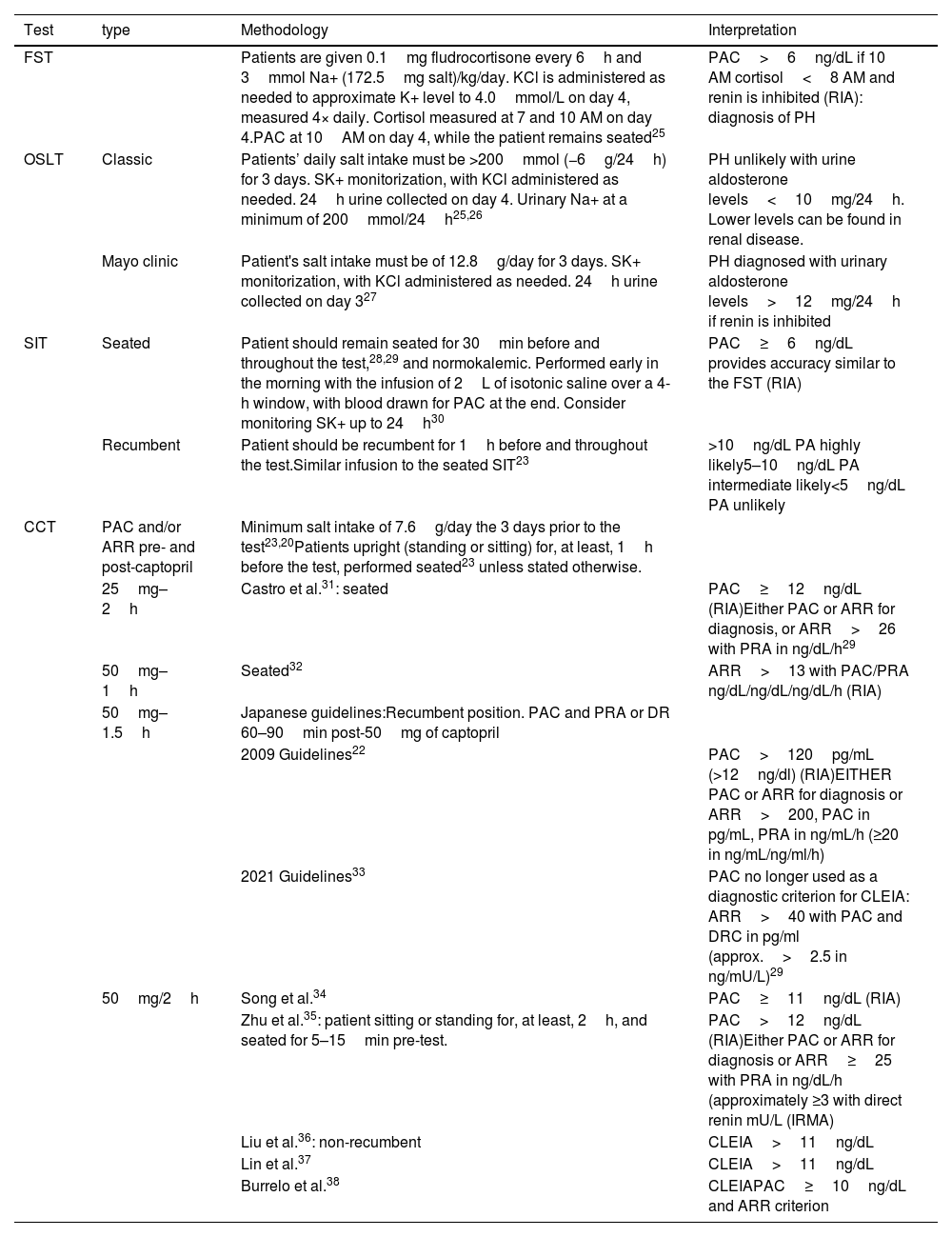

Confirmatory testsFour confirmatory tests may be used to establish the biochemical definitive diagnosis of PH: the fludrocortisone suppression test (FST), the oral salt loading test (OSLT), the saline infusion test (SIT), and the captopril challenge test (CCT)23 (Table 4). Two tests are more widely used to diagnose PH: the saline infusion test (SIT) and the captopril challenge test (CCT), both of which can be performed in an outpatient setting.

Dynamic test for PH confirmation.

| Test | type | Methodology | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FST | Patients are given 0.1mg fludrocortisone every 6h and 3mmol Na+ (172.5mg salt)/kg/day. KCl is administered as needed to approximate K+ level to 4.0mmol/L on day 4, measured 4× daily. Cortisol measured at 7 and 10 AM on day 4.PAC at 10AM on day 4, while the patient remains seated25 | PAC>6ng/dL if 10 AM cortisol<8 AM and renin is inhibited (RIA): diagnosis of PH | |

| OSLT | Classic | Patients’ daily salt intake must be >200mmol (−6g/24h) for 3 days. SK+ monitorization, with KCl administered as needed. 24h urine collected on day 4. Urinary Na+ at a minimum of 200mmol/24h25,26 | PH unlikely with urine aldosterone levels<10mg/24h. Lower levels can be found in renal disease. |

| Mayo clinic | Patient's salt intake must be of 12.8g/day for 3 days. SK+ monitorization, with KCl administered as needed. 24h urine collected on day 327 | PH diagnosed with urinary aldosterone levels>12mg/24h if renin is inhibited | |

| SIT | Seated | Patient should remain seated for 30min before and throughout the test,28,29 and normokalemic. Performed early in the morning with the infusion of 2L of isotonic saline over a 4-h window, with blood drawn for PAC at the end. Consider monitoring SK+ up to 24h30 | PAC≥6ng/dL provides accuracy similar to the FST (RIA) |

| Recumbent | Patient should be recumbent for 1h before and throughout the test.Similar infusion to the seated SIT23 | >10ng/dL PA highly likely5–10ng/dL PA intermediate likely<5ng/dL PA unlikely | |

| CCT | PAC and/or ARR pre- and post-captopril | Minimum salt intake of 7.6g/day the 3 days prior to the test23,20Patients upright (standing or sitting) for, at least, 1h before the test, performed seated23 unless stated otherwise. | |

| 25mg–2h | Castro et al.31: seated | PAC≥12ng/dL (RIA)Either PAC or ARR for diagnosis, or ARR>26 with PRA in ng/dL/h29 | |

| 50mg–1h | Seated32 | ARR>13 with PAC/PRA ng/dL/ng/dL/ng/dL/h (RIA) | |

| 50mg–1.5h | Japanese guidelines:Recumbent position. PAC and PRA or DR 60–90min post-50mg of captopril | ||

| 2009 Guidelines22 | PAC>120pg/mL (>12ng/dl) (RIA)EITHER PAC or ARR for diagnosis or ARR>200, PAC in pg/mL, PRA in ng/mL/h (≥20 in ng/mL/ng/ml/h) | ||

| 2021 Guidelines33 | PAC no longer used as a diagnostic criterion for CLEIA: ARR>40 with PAC and DRC in pg/ml (approx.>2.5 in ng/mU/L)29 | ||

| 50mg/2h | Song et al.34 | PAC≥11ng/dL (RIA) | |

| Zhu et al.35: patient sitting or standing for, at least, 2h, and seated for 5–15min pre-test. | PAC>12ng/dL (RIA)Either PAC or ARR for diagnosis or ARR≥25 with PRA in ng/dL/h (approximately ≥3 with direct renin mU/L (IRMA) | ||

| Liu et al.36: non-recumbent | CLEIA>11ng/dL | ||

| Lin et al.37 | CLEIA>11ng/dL | ||

| Burrelo et al.38 | CLEIAPAC≥10ng/dL and ARR criterion |

PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration; PRA, plasma renin activity; ARR, aldosterone–renin-ratio; RIA, radioimmunoassay; IRMA, immunoradiometric assay; CLEIA, chemiluminescence; ST, fludocortisone suppression test; OSLT, oral salt loading test; SIT, saline infussion test; CCT, captopril challenge test; PH, primary hyperaldosteronism.

Familial forms of PH account for nearly 1% up to 6%% of all reported PH and should be identified, and, if possible, genotyped.

Low-renin HTN with mild aldosteronism to identity positive response groups to MRA for HTN control should be identified too. Cortisol co-secretion, present in up to 30% of PH must be screened. Differential diagnosis with other PH-like entities such as salt loss tubulopathies, Cushing syndrome, Liddle syndrome, apparent mineralocorticoid excess, 11-beta- and 17-alfa hydroxylase and pseudohyperaldosteronism type II should be considered. In special situations such as older patients, chronic kidney disease and pregnant women PH must be paid special attention.16

Subtype diagnosis- -

Imaging modalities: Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are 2 imaging modalities widely used for diagnosis. Concordance across multiple imaging modalities, mostly CT, to establish laterality only occurs 62% of the time.39 For this reason, the recommendation is to perform an AVS in all PH patients who are eligible for adrenalectomy. However, in patients younger than 35 years with PH who exhibit spontaneous hypokalemia, a significant aldosterone excess, an adrenal adenoma, and a normal contralateral gland on the CT/MRI, or in those with an adrenal tumor with radiological features of adrenocortical carcinoma, we can directly go to adrenalectomy without AVS39,40 (Fig. 1).

- -

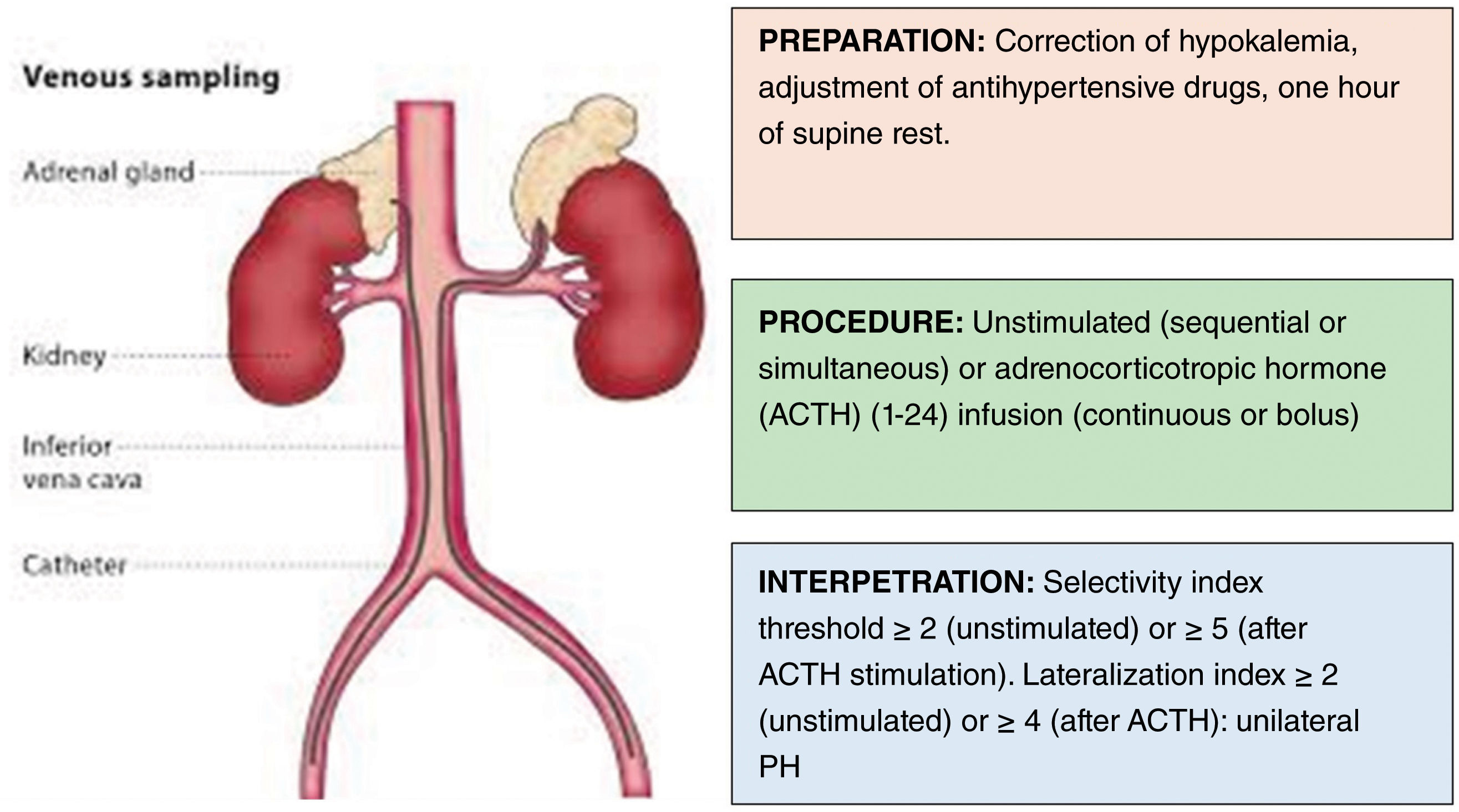

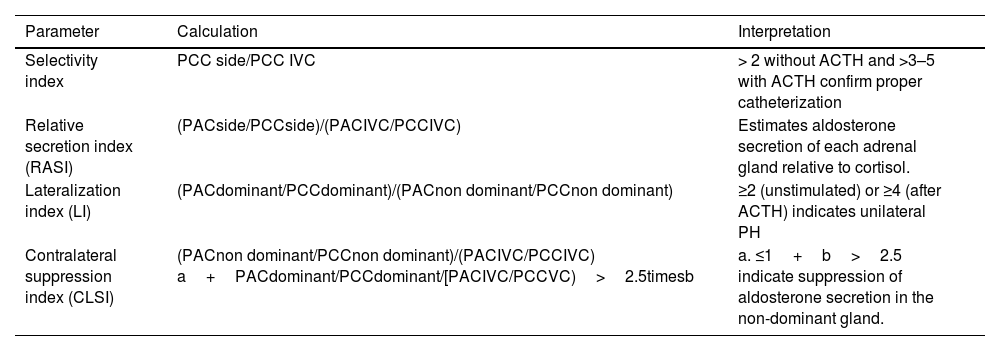

Adrenal venous sampling (AVS): AVS is a technically complex procedure whose success is highly dependent on the availability of skilled interventional radiologists from high-volume referral centers. The first step to interpret AVS data is to make sure that the catheters were properly positioned in the adrenal veins, and then calculate the selectivity index for each adrenal side. After confirmation of this first assumption, the lateralization index will show whether the PH is unilateral or bilateral (Fig. 2 and Table 5). Furthermore, in patients with a lateralization index<4, suppressing aldosterone secretion in the gland contralateral to the adenomatous one may be indicative of unilateral secretion.41

Table 5.Parameters to calculate in the adrenal venous sampling for PH subtyping.42

Parameter Calculation Interpretation Selectivity index PCC side/PCC IVC > 2 without ACTH and >3–5 with ACTH confirm proper catheterization Relative secretion index (RASI) (PACside/PCCside)/(PACIVC/PCCIVC) Estimates aldosterone secretion of each adrenal gland relative to cortisol. Lateralization index (LI) (PACdominant/PCCdominant)/(PACnon dominant/PCCnon dominant) ≥2 (unstimulated) or ≥4 (after ACTH) indicates unilateral PH Contralateral suppression index (CLSI) (PACnon dominant/PCCnon dominant)/(PACIVC/PCCIVC) a+PACdominant/PCCdominant/[PACIVC/PCCVC)>2.5timesb a. ≤1+b>2.5 indicate suppression of aldosterone secretion in the non-dominant gland. Dominant, side with higher plasma aldosterone concentration; IVC, inferior vena cava; non dominant, contralateral side; PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration; PCC, plasma cortisol concentration.

PH should be treated medically with MRA, whereas unilateral adrenalectomy is the preferred therapeutic option for unilateral PH (Fig. 1). PH treatment aims to normalize BP and mitigate the deleterious effects of excessive aldosterone production to eventually reduce comorbidities, enhance quality of life, and lower mortality.

Surgical treatmentTotal adrenalectomy is the gold standard for removing hypersecretory aldosterone tissue. Minimally invasive or open surgery (laparoscopic or robotic techniques) can be performed using an anterior, lateral, or posterior approach.43 BP levels usually improve within the first 6 months of treatment. Biochemical remission is reported in 94% of patients, clinical response in 41%, with only 42% achieving total resolution (i.e., cure of HT).14,44

Pathology studyCombining morphology and immunostaining for CYP11B2 methods the new HISTALDO classification can predict the risk of recurrence after unilateral resection. Six diagnostic categories are described: aldosterone-producing (AP) cortical carcinoma, AP adenoma, AP nodule, AP micronodule (previously known as cell clusters), multifocal AP nodules and/or micronodules, and AP diffuse hyperplasia. Germline mutations, like KCNJ5 are typically present also in sporadic AP adenomas.45

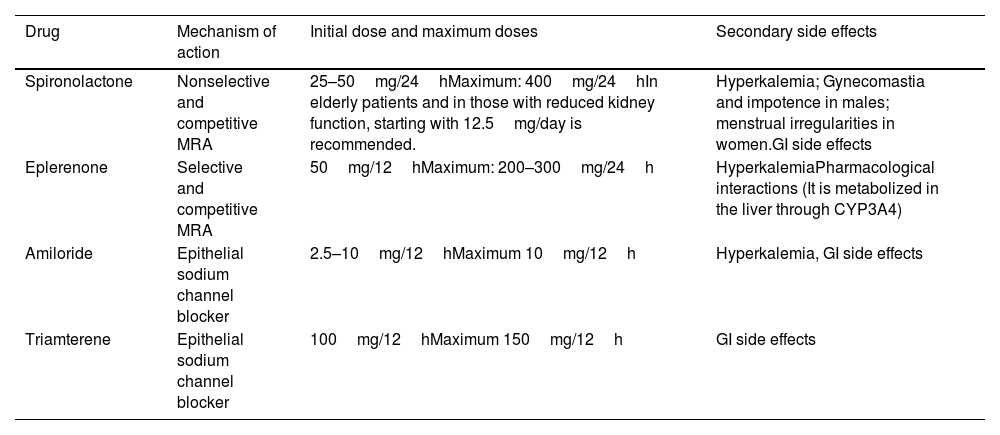

Medical treatmentMedical treatment of PH aims to limit organ damage (mainly at the cardiovascular and renal levels), morbidity and mortality due to aldosterone excess and HTN and correct hypokalemia. The main drugs used for this purpose are MRA, which have proven effective for BP control and correction of the effect of the aldosterone excess.46 Medical treatment should be considered for patients with bilateral disease or if surgery has been ruled out due to other clinical conditions. The targeted medical treatment of PH is described in Table 6

Medical treatment of PH.28

| Drug | Mechanism of action | Initial dose and maximum doses | Secondary side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone | Nonselective and competitive MRA | 25–50mg/24hMaximum: 400mg/24hIn elderly patients and in those with reduced kidney function, starting with 12.5mg/day is recommended. | Hyperkalemia; Gynecomastia and impotence in males; menstrual irregularities in women.GI side effects |

| Eplerenone | Selective and competitive MRA | 50mg/12hMaximum: 200–300mg/24h | HyperkalemiaPharmacological interactions (It is metabolized in the liver through CYP3A4) |

| Amiloride | Epithelial sodium channel blocker | 2.5–10mg/12hMaximum 10mg/12h | Hyperkalemia, GI side effects |

| Triamterene | Epithelial sodium channel blocker | 100mg/12hMaximum 150mg/12h | GI side effects |

MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

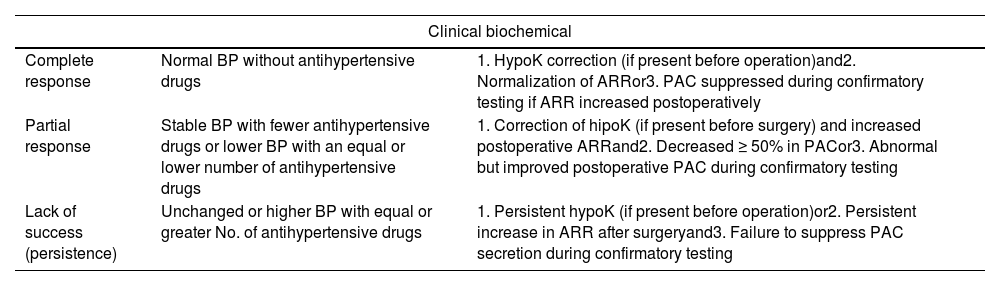

The Primary Aldosteronism Outcome (PASO) criteria14 should be applied to surgically treated PH (Table 7). Following surgery, PAC and renin levels should be measured to assess biochemical response. As it happens with the screening ARR of diagnostic testing, at least, 4 weeks should go by before measuring PAC and renin levels for the effect of prior MRA to pass. On the first postoperative day, MRA should be discontinued, and potassium supplementation should be withdrawn based on kalemia. Postoperative potassium and sodium changes should be prevented.15

Definition of surgical outcomes in PH.14

| Clinical biochemical | ||

|---|---|---|

| Complete response | Normal BP without antihypertensive drugs | 1. HypoK correction (if present before operation)and2. Normalization of ARRor3. PAC suppressed during confirmatory testing if ARR increased postoperatively |

| Partial response | Stable BP with fewer antihypertensive drugs or lower BP with an equal or lower number of antihypertensive drugs | 1. Correction of hipoK (if present before surgery) and increased postoperative ARRand2. Decreased ≥ 50% in PACor3. Abnormal but improved postoperative PAC during confirmatory testing |

| Lack of success (persistence) | Unchanged or higher BP with equal or greater No. of antihypertensive drugs | 1. Persistent hypoK (if present before operation)or2. Persistent increase in ARR after surgeryand3. Failure to suppress PAC secretion during confirmatory testing |

BP, blood pressure; hipoK, hypokalemia; ARR, aldosterone–renin-ratio; PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration. Clinical and biochemical cure is, also, a demonstration of the unilateral nature of PH, and, respectively, of PH.

Serum potassium should be tested 3–5 days after surgery. Improvement in BP usually shows maximum improvement 1 to 6 months after adrenalectomy. Thus, outcome assessment (clinical and biochemical) should be performed 3 months after surgery. If cortisol co-secretion, consider glucocorticoid substitution.

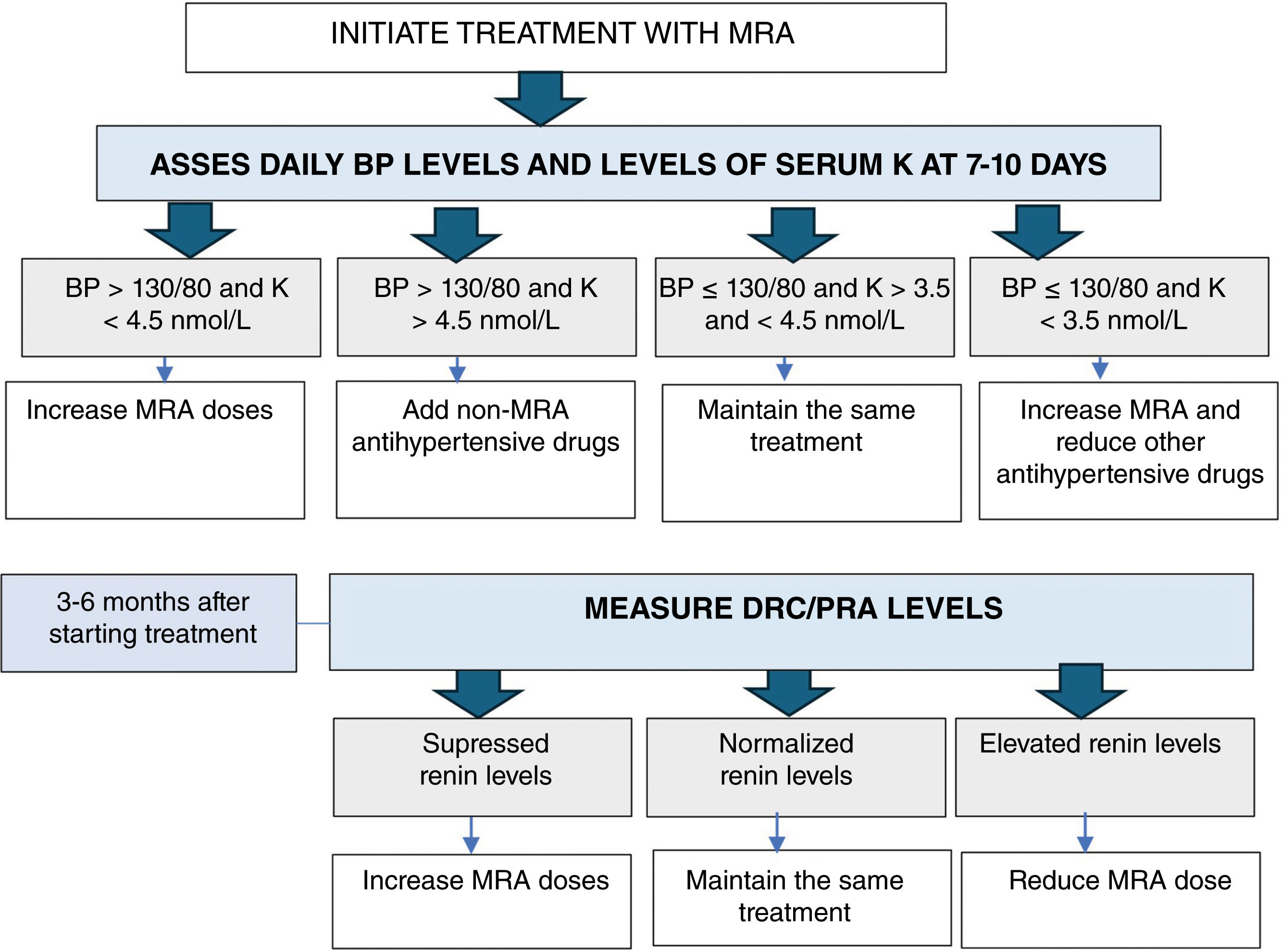

Follow-up in medically treated patientsMedical treatment aims to achieve a BP<130/80mmHg, normal serum potassium levels, and normalization of plasma renin levels or the ARR while reducing other antihypertensive drugs. It is essential to achieve an unsuppressed renin to reduce the number of cardiovascular and metabolic events and death at the long-term follow-up in medically treated PA6,47 (Fig. 3).

ConclusionsPH is the most common cause of secondary HTN and is associated with a higher cardiometabolic risk than essential HTN. Nevertheless, it remains underdiagnosed. The diagnosis of PH should be achieved following 3 steps: (1) case detection with ARR determination; (2) case confirmation using 1 or more confirmatory tests; and (3) subtype differentiation using imaging modalities (CT and/or MRI) and AVS in most cases. MRA and surgical treatment are effective in controlling BP and reducing associated cardiovascular risks.

Spanish Society of Endocrinology, Nutrition (SEEN), Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC), Spanish Society of Nephrology (SEN), Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI), Spanish Society of Radiology (SERAM), Spanish Society of Vascular, Interventional Radiology (SERVEI), Spanish Society of Laboratory Medicine (SEQC(ML)), Spanish Society of Anatomic-Pathology, and Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC).