Herlyn–Werner–Wunderlich syndrome is an uncommon urogenital anomaly defined by uterus didelphys, obstructed hemi-vagina and unilateral renal anomalies. The most common clinical presentation is dysmenorrhoea following menarche, but it can also present as pain and an abdominal mass.

Prader–Willi syndrome is a rare neuroendocrine genetic syndrome. Hypothalamic dysfunction is common and pituitary hormone deficiencies including hypogonadism are prevalent.

We report the case of a 33-year-old female with Prader–Willi syndrome who was referred to the Gynaecology clinic due to vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a haematometra and haematocolpos and computed tomography showed a uterus malformation and a right uterine cavity occupation (hematometra) as well as right kidney agenesis.

Vaginoscopy and hysteroscopy were performed under general anaesthesia, finding a right bulging vaginal septum and a normal left cervix and hemiuterus. Septotomy was performed with complete haematometrocolpos drainage. The association of the two syndromes remains unclear.

El síndrome de Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich es una anomalía urogenital infrecuente definida por útero didelfo, hemivagina obstruida y anomalías renales unilaterales. La presentación clínica más común es la dismenorrea después de la menarquia, pero también puede presentarse como dolor y masa abdominal.

El síndrome de Prader-Willi es un síndrome genético neuroendocrino poco común. A menudo se acompaña de disfunción hipotalámica y son frecuentes las deficiencias de hormonas hipofisarias, incluido el hipogonadismo.

Se presenta el caso de una mujer de 33 años con síndrome de Prader-Willi que acude a consulta de Ginecología por sangrado vaginal y dolor abdominal. La ecografía abdominal reveló hematometra y hematocolpos. Mediante tomografía computarizada se evidenció una malformación del útero y una ocupación de la cavidad uterina derecha (hematometra), así como agenesia del riñón derecho.

Se realizó vaginoscopia e histeroscopia bajo anestesia general, encontrándose un tabique vaginal derecho abultado, y un cuello uterino y hemiútero izquierdos normales. Se realizó septotomía con drenaje completo del hematometrocolpos. La asociación de ambos síndromes no está clara.

We report the case of a 33-year-old female, with a medical history of Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS), diagnosed at birth due to neonatal hypotonia, inability to suck and characteristic phenotype. Genetic confirmation showed microdeletion at 15q11q13 of type II on the paternal allele.

She has multiple comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, GH deficiency, obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome, cataract, intellectual disability, morbid obesity and osteopenia.

During puberty she was diagnosed with type III obesity, with an oscillating BMI ranging from 51 to 56, until the current year. Since 2017, she has been undergoing treatment with growth hormone (GH) at a daily dosage of 0.8mg. At the time of the initial diagnosis, she did not meet the criteria to start GH treatment. Prior to GH therapy, a densitometry assessment showed that she had lumbar and femoral osteopenia (lumbar T score −1.78 Z score −3.11; femur T score −1.64 Z score −2.65). With the introduction of GH supplementation there was an improvement in bone density (lumbar T score −1.16 Z score −2.49).

The management of type II diabetes, diagnosed at the age of 17, initially involved a combination of metformin and insulin starting in 2006. In 2013, subclinical non-autoimmune primary hypothyroidism was diagnosed. Currently, she is euthyroid and does not require hormone supplementation.

At the last routine visit, the patient reported a five-day history of abnormal vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain, whilst she previously had primary amenorrhoea.

Routine blood tests performed during follow-up from the ages of 13 to 23 showed FSH and LH values below 1mIU/ml and oestradiol levels below 20pg/ml. From the age of 23 to the present, her gonadotropin levels increased to values around 5mIU/ml and oestradiol levels to between 20 and 30pg/ml, suggesting a central hypothalamic cause of the amenorrhoea.

She was referred to Gynaecology with vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain. She had no previous menstruation, and she had never received hormone treatment before. She was not sexually active. An abdominal ultrasound was performed, with suboptimal visualisation due to morbid obesity, revealing a voluminous haematometra and haematocolpos. An obstructed vagina due to a transverse vaginal septum was initially suspected but other uterus malformations could not be ruled out.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and diagnostic hysteroscopy/vaginoscopy were requested to classify and study a suspected uterine anomaly. The hormone analysis showed the following hormonal levels: prolactin 14.7ng/ml (4.79–23.30); FSH 2.93mIU/ml (3.50–12.50); LH 2.7mIU/ml (2.40–12.60); and oestradiol 44pg/ml (13–166).

Before the MRI scan could be performed, she came to Accident and Emergency (A&E) complaining of increased abdominal pain. She had only had one other menstrual bleed in four months. She was initially admitted to the surgery department, suspecting an acute abdomen, so an emergency computed tomography (CT) scan was performed to exclude appendicitis.

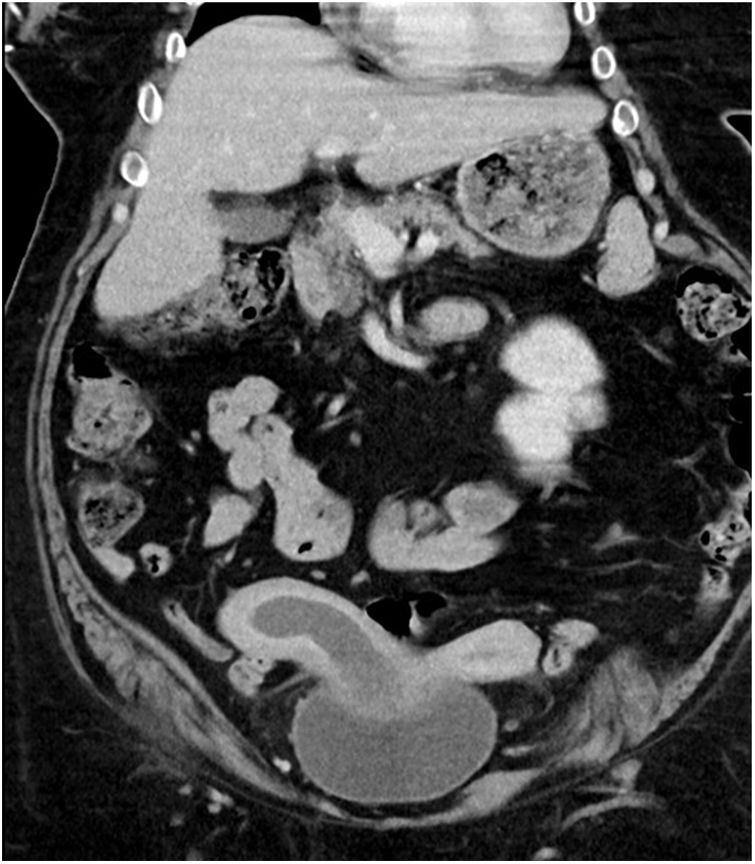

The CT scan revealed a uterus malformation suggestive of uterus didelphys and a right uterine cavity occupation (haematometrocolpos) as well as the absence of a right kidney.

In A&E, intravenous analgesia had been administered, and so the patient was discharged with no abdominal pain at that point.

The radiological findings of an obstructed septate vagina, uterus didelphys and renal agenesis suggested Herlyn–Werner–Wunderlich syndrome as a preliminary diagnosis in this case (Fig. 1).

Due to the associated pathology, endoscopic surgical intervention was performed under general anaesthetic in an operating theatre, using a 5.5mm hysteroscope (Olympus®) with a 30-degree optics connected to an automatic fluid pump (Aesculap®) infusing isotonic normal saline solution to distend the cavity at a constant pressure of 80mmHg.

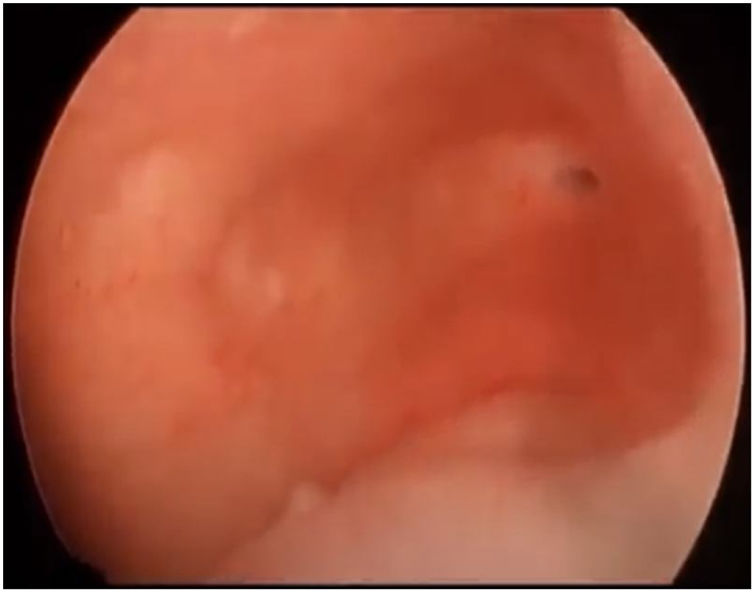

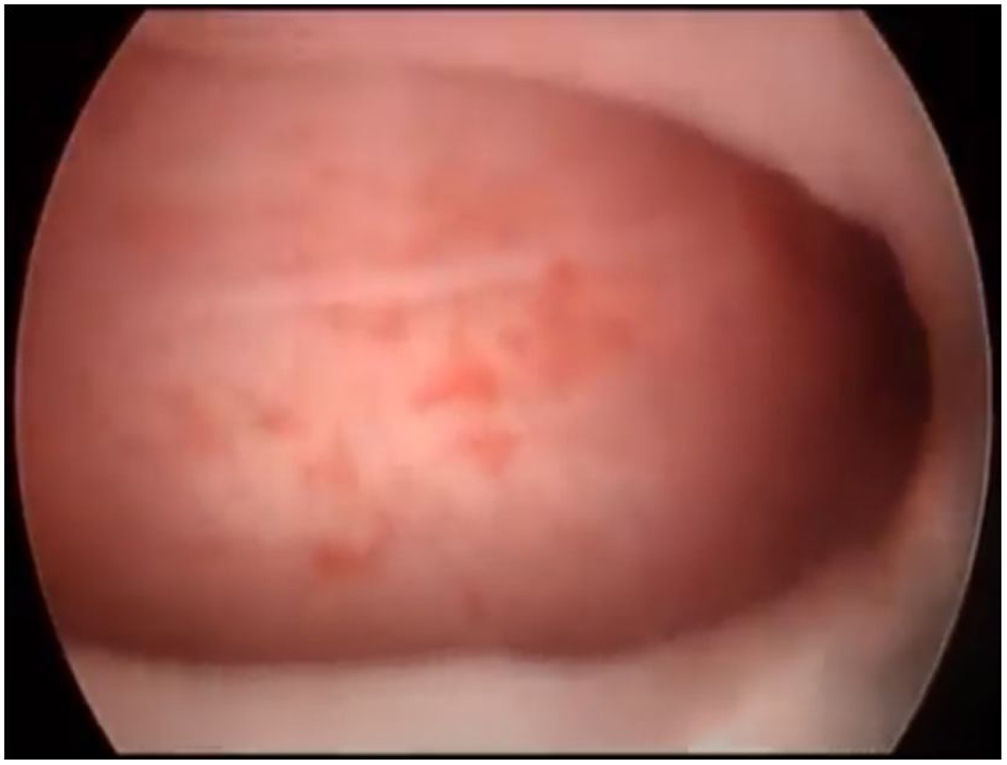

First, operative vaginoscopy was performed, visualising both vaginal fornices, and the external cervical os of the accessible hemivagina. Hysteroscopy was performed visualising a tubular cavity with a single tubal ostium. After retraction of the hysteroscope to the vagina, a right bulging vaginal septum was observed suggesting a right haematometrocolpos. Longitudinal septotomy was performed using a Collins electrosurgical bipolar electrode (Olympus®) from the upper segment of the vagina to the distal part, with drainage of blood content (Figs. 2 and 3).

At the end of the procedure, a normal right cervix and uterus were observed. There were no complications.

During follow-up, the patient had three spontaneous menstruations and no abdominal pain. Afterwards, ultrasound showed mild right haematometra without haematocolpos.

Currently, the patient continues under multidisciplinary and clinical gynaecology follow-up with regular menstruations and she is pain-free.

Management and evidencePWS is a rare genetic disorder caused by the lack of expression of paternal genes located on chromosome 15q11-13. It can result from paternal deletion, maternal uniparental disomy, from genomic imprinting centre defects or sporadic cases. The estimated prevalence is 1:10,000–1:30,000 new-borns. It can be diagnosed during the neonatal period due to a severe hypotonia and feeding difficulties. Temperamental behaviour, some degree of intellectual disability and excessive eating leading to early morbid obesity are common, as well as hypothalamic dysfunction combined with specific dysmorphisms.1–4

Pituitary hormone deficiencies are a usual finding in PWS patients, namely growth hormone (GH) deficiency and gonadotropin deficiency, causing hypogonadism with a prevalence of 54–100% in women with PWS. Although there is generally a normal onset of puberty with breast development, its progression is often delayed and incomplete and spontaneous menarche does not usually occur.5–7

Hypogonadism in women with PWS is defined as absent or irregular menstruation, regardless of serum oestradiol levels. This may be mainly due to a central cause, less frequent primary hypogonadism or both.6–10

Central hypogonadism is defined as absent or irregular menstrual cycle either in the presence of serum luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) concentrations below the reference range, or combined with a low oestradiol concentration in the presence of serum LH and FSH concentrations within the reference range. Primary hypogonadism is defined as an absent or irregular menstrual cycle with serum LH and FSH concentrations above the reference range.1–8

Although most of PWS features have been attributed to a primary defect in hypothalamic function, primary ovarian dysfunction also seems to contribute to hypogonadism, causing irregular menses or even secondary amenorrhoea in some cases.9 If menarche occurs spontaneously, it is often delayed (at a mean age of 20 years) and followed by irregular menstruations or secondary amenorrhoea. Some have bleeds, most likely caused by the unopposed action of oestrogens originating peripherally from adipose tissue.10

Furthermore, in obese patients, oestradiol levels can be within the reference range despite dysfunction of the hypothalamus, pituitary or ovaries, due to increased aromatase activity in adipose tissue.10

Therefore, laboratory measurements should be performed to determine the type of hypogonadism and to exclude hyperprolactinaemia. Hyperprolactinaemia is a common adverse effect of some antipsychotics taken by many of these patients, and hyperprolactinaemia might result in hypogonadism.

Based on the recently suggested clinical recommendations from the Dutch Cohort Study, assessment of gonadal function and systematic screening for hypogonadism should be carried out on all women with PWS to avoid the negative consequences of long-term untreated hypogonadism, especially on bone mineral density (BMD).11,12

Additionally, a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan should be performed as the risk of osteoporosis or osteopenia makes treatment with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) more urgent.

Following expert recommendations, the treatment of hypogonadism is recommended in all adult females with PWS. Many beneficial effects of HRT have been described, including beneficial effects on bone health, muscle and fat, psychological outcomes, and cardiovascular health. Some of these beneficial effects are especially important for patients with PWS as they already have a higher risk of developing abnormal body composition, psychological problems and cardiovascular disease.

As patients with PWS have abnormal body composition with a high fat mass and low lean body mass, oestrogen might help to improve their body composition. However, there are no consensus statements as to the most appropriate regimen of sex hormone treatment in PWS.11,12

Although adequate treatment is important for patient well-being, the Dutch Cohort study concludes that, according to the guidelines for indications and contraindications for the use of HRT, even with hypogonadism, women with BMI higher than 30 or other comorbidities cannot receive HRT. HRT can increase the risk of thrombosis13 and patients with PWS already have a higher risk of thrombotic events. It is important to avoid any other risk factors for thrombosis, if possible, including smoking, obesity and immobility.14

Our patient, with a central cause of hypogonadism diagnosed by blood analysis, had not previously been assessed by Gynaecology with an ultrasound scan due to her intellectual disability and comorbidities. For this reason and her high risk of thrombosis, hormone replacement was not considered. Despite her osteopenia other alternative measures were preferred.

Herlyn–Werner–Wunderlich syndrome (HWWS), also known as OHVIRA syndrome (obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly) is a rare female congenital malformation affecting the female urogenital tract caused by abnormal development of the Müllerian and mesonephric duct during embryogenesis.15 The prevalence of HWWS is not firmly established, but obstructive Müllerian anomalies are reported in 0.1–3.8% of the population, with HWWS representing approximately 5% within this group.16,17

Several variants of this obstructive condition are identified but most (80%) are characterised by a triad consisting of didelphys uterus, obstructed hemi-vagina and ipsilateral renal anomalies, primarily agenesis. Less frequently, the uterine malformation may be a septate uterus or bicornuate uterus. The unilateral genital obstruction associated with this syndrome is mainly vaginal, although sporadic reports mention cervical obstruction or atresia. Duplicated and dysplastic kidney may also be found.16–18

For accurate and comprehensive classification encompassing all variants, the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) classifications, in accordance with the consensus on the classification of female genital tract congenital anomalies published in 2013, are considered the most suitable.16 However, a new classification from the American Society of Reproductive medicine is currently being proposed.18 When applying the ESHRE/ESGE classification, anomalies are classified based on anatomy, expressing uterine anatomical deviations (U) derived from the same embryological origin. These main classes are further divided into subclasses expressing anatomical variants, while cervical and vaginal anomalies are classified independently. According to this system, our patient was classified as a U3C2V3.

Patients with HWWS are usually asymptomatic until menarche. Once symptoms manifest, the most common complaints include abdominal pain, severe dysmenorrhoea, pelvic mass and spotting. Diagnosis is often made after menarche, when the obstructed hemi-vagina blocks the evacuation of the hemiuterus leading to haematocolpos and secondary haematometra. The lack of proper evacuation can result in retrograde blood flow causing endometriosis and infertility. Some patients may experience intermenstrual bleeding due to having an incomplete vaginal septum or when uterine cavities communicate.

When HWWS is suspected, two and three-dimensional ultrasounds (2D/3D) can be useful as an initial diagnostic approach. However, MRI is more adept at characterising and classifying genitourinary malformation and pinpointing obstruction sites.19–21

The treatment for a patient diagnosed with double uterus and obstructed hemivagina is generally limited to the excision of the obstructive septum to relieve patient symptoms, presuming an association with a didelphys uterus. It is crucial to clarify the uterine type and consider rare variants of this syndrome.

Surgical treatment for this condition with the classic variant is usually performed in the operating theatre, but there are new procedures, such as outpatient clinic hysteroscopy, with very similar results and high satisfaction rates.22 The current surgical approach consisting of an incision of the vaginal septum (septotomy), in order to drain the haematocolpos/haematometra via vaginoscopy, offers symptom relief.

In our patient, the diagnosis was not established until menarche at the age of 30, and due to her comorbidity, the procedure had to be performed in the operating theatre with sedation.

Areas of uncertaintyWe report a case of a female adult diagnosed with PWS and HWWS. To the best of our knowledge, only one other case of such an association has been reported in the literature. In this case, the diagnosis of renal agenesis was made prenatally, and the uterine anomaly was confirmed at birth.23 Prenatal diagnosis techniques have evolved greatly over the last twenty or thirty years and this will allow more and earlier diagnoses than when our patient was born.

There are no references to a possible relationship between PWS and HWWS, but the above-mentioned study23 suggests that, although unlikely, a relationship between PWS and Müllerian anomalies could be considered. Considering the possibility that hypogonadism in PWS may be due to primary gonadal abnormalities, the association between the two syndromes could be more than coincidental. Both syndromes are considered forms of sexual differentiation disorders (DSD).

In view of advances in the discovery of genetic causes for many of these DSD, in the future it may be possible to find an association between the two syndromes.

In this patient the earlier diagnosis would not probably have changed the therapeutic approach given that none of the analytical parameters were indicative of future menarche.

GuidelinesWe consulted the Dutch cohort study published by the international expert panel on PWS in which a guideline for action and treatment of hypogonadism is proposed, as well as other published review documents.

The ESHRE/ESGE consensus document for the classification of congenital anomalies of the female genital tract and variants, and the review of published articles on clinical, diagnostic and treatment considerations of the HWW syndrome were used to write this article.

Conclusions and recommendationsAlthough a large percentage of patients with HPW have primary amenorrhoea of central cause, a small percentage may have menstruation regardless of their hormonal level.

The possibility of monitoring these patients by multidisciplinary teams allows for more individualised diagnosis and treatment.

HWWS must be suspected in a patient with cyclic abdominal pain and imaging findings consistent with haematocolpos or haematometra.

The association between the two syndromes, although very unlikely, cannot be ruled out.

Authors’ contributionsThe first manuscript draft was written by LC, EG and LT and reviewed by AC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethical approvalWritten informed consent was obtained from the family of the patient for publication of this case and any accompanying images.

FundingThe authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.