Iodine deficiency is an important public health concern and much time and effort has been spent in seeking to eradicate the problem over the last 80 years.1 Pregnant women are particularly sensitive in this regard, due to their increased iodine requirements during pregnancy. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a daily iodine intake of 250μg. A median urine excretion (ioduria) of 150–249μg/l is indicative of adequate intake, while <150μg/l is considered insufficient, 250–499μg/l is above what the body needs, and >500μg/l is considered excessive.2

Iodine nutritional status in the Spanish population is currently adequate.3 In contrast to iodine deficiency, excesses from dietetic sources are infrequent here. However, the generalized use of iodized pharmacological supplements in pregnant women, together with the largely uncontrolled increase in the iodine contents of dietetic sources (silent iodoprophylaxis), and other potential contributing factors such as the use of iodized antiseptics, can result in excessive intake – with consequent but less well-known repercussions upon maternal thyroid gland function.4

A study was made of 106 healthy pregnant women with normal thyroid function and negative thyroid immune findings. We determined the levels of TSH, FT3 and FT4 in the first (week 10–12) and third trimester (week 34–36) with a chemiluminescence microparticle immunoassay in an ARCHITEC analyzer (Abbott Ireland Diagnosis Division, Linamuck, Longford, Ireland). In the case of TSH the sensitivity of the assay is ≤0.01μIU/ml, and the normality value (NV) ranges from 0.49 to 4.67μIU/ml; the specificity of the assay is <10% cross-reactivity with TSH, FSH and hCG. In the case of FT4, the limit of detection is ≤0.4ng/dl, and the NV is 0.70–1.59ng/dl; the specificity of the assay is ≤0.0035% cross-reactivity with T3. In the case of FT3, the limit of detection is ≤1pg/dl, and the NV is 1.71–3.71pg/dl; the specificity of the assay is <0.001% cross-reactivity with T4. In addition, we collected a sample of first morning urine to determine ioduria using high performance liquid chromatography (Immunochrom GMbh, Heppenheim, Germany). The intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variation was <3.5% and <4.8%, respectively, with a sensitivity of 0.02μmol/l.

The mean age of the pregnant women was 31.5±4.7 years, with a body mass index (BMI) of 24.4±5.0kg/m2. There were 25 smokers (23.5%). Forty-two women were in their first pregnancy (39.6%), and 26 had a history of at least one aborted pregnancy (24.5%). Iodized salt was consumed by 42 patients (39.6%) in the first trimester and by 100 (94.3%) in the last trimester (p<0.05). Pharmacological supplements were being used by 79 patients (74.5%) in the first trimester and by 102 (96.2%) in the last trimester (p<0.05).

Median ioduria in the first trimester was 171.31μg/l (interquartile range [IQR] 184.18) versus 190.37μg/l (IQR 263.56) in the third (p=ns). Only 20 pregnant women in the first trimester (18.8%) and 25 in the third trimester (23.5%) showed optimum ioduria levels (defined as 150–249μg/l). However, a decrease was observed in the number of women with ioduria <150μg/l, from 50 in the first trimester (47.1%) to 39 in the third (37.7%). By contrast, the number of pregnant women with ioduria ≥250μg/l increased from 36 in the first trimester (33.9%) to 42 in the third (39.6%).

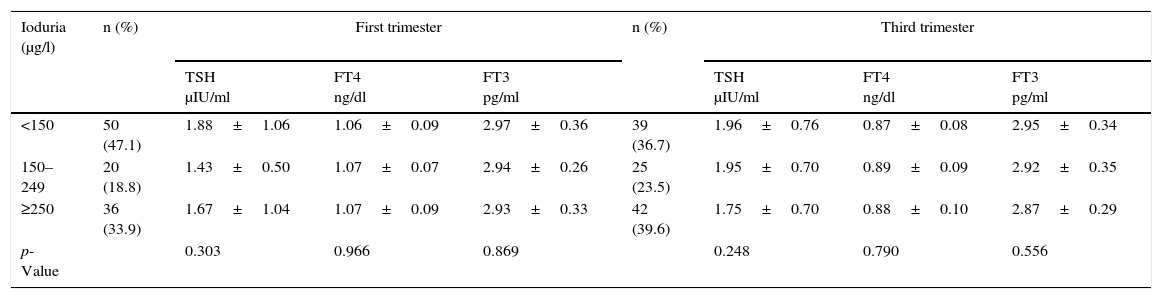

Table 1 shows the relationship between ioduria and the different thyroid function parameters in both the first and the second trimester of pregnancy. Although the women with adequate ioduria (150–249μg/l) presented lower TSH levels in the first trimester, the difference was not significant. No differences were observed in the FT3 or FT4 levels between the groups.

Thyroid function parameters according to ioduria level.

| Ioduria (μg/l) | n (%) | First trimester | n (%) | Third trimester | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSH μIU/ml | FT4 ng/dl | FT3 pg/ml | TSH μIU/ml | FT4 ng/dl | FT3 pg/ml | |||

| <150 | 50 (47.1) | 1.88±1.06 | 1.06±0.09 | 2.97±0.36 | 39 (36.7) | 1.96±0.76 | 0.87±0.08 | 2.95±0.34 |

| 150–249 | 20 (18.8) | 1.43±0.50 | 1.07±0.07 | 2.94±0.26 | 25 (23.5) | 1.95±0.70 | 0.89±0.09 | 2.92±0.35 |

| ≥250 | 36 (33.9) | 1.67±1.04 | 1.07±0.09 | 2.93±0.33 | 42 (39.6) | 1.75±0.70 | 0.88±0.10 | 2.87±0.29 |

| p-Value | 0.303 | 0.966 | 0.869 | 0.248 | 0.790 | 0.556 | ||

Data reported as the mean±standard deviation.

p<0.05 was considered significant.

Only 39.6% of the pregnant women in this study consumed iodized salt in the first trimester. This percentage was far below the level considered necessary to ensure an adequate dietetic supply, and it was particularly worrying given that prolonged consumption for at least two years is required in order to reduce the risk of thyroid gland dysfunction during pregnancy.5 The significant increase in consumption observed following the recommendation reflects the importance of the promotional measures taken.

Iodized supplements were predominantly used. However, only 11 of the 79 pregnant women who used these supplements in the first trimester started to use them at least 8 weeks before admission to the study. These women presented lower mean TSH values than those who started taking the supplements later (1.22μIU/ml±0.6 vs 1.78μIU/ml±1.0), though the difference was not significant (p=0.13). This effect has been previously described and was attributed to a stunning effect on the thyroid gland secondary to a sudden rise in iodine levels.6

Thyroid function problems related to iodine deficiency are well known.7 In the present study, ioduria <150μg/l did not result in significant changes in any of the thyroid function parameters versus the pregnant women with ioduria 150–249μg/l. However, only 7 women (6.6%) in the first trimester and 5 in the third (4.7%) presented ioduria <50μg/l, these being the patients with the highest risk of thyroid gland dysfunction.8

Iodine excess can also affect thyroid function.9 The pregnant women in our study with ioduria ≥250μg/l showed no differences in thyroid function parameters versus the women with ioduria values within the optimum range. In a previous study, pregnant women with a median ioduria >1000μg/l showed higher TSH levels and a greater prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism.10 However, in our study only two women in the third trimester of pregnancy versus none in the first trimester presented ioduria >1000μg/l.

As the main limitation of our study, mention must be made of the great intra- as well as inter-individual variability of ioduria, which can cause classification errors when the sample is being divided into sub-groups.

In conclusion, the pregnant women of this study showed adequate iodine status. The use of iodized pharmacological supplements was a predominant practice from the early stages of pregnancy, though not so the consumption of iodized salt. Maternal thyroid function showed no significant differences in the different iodine ranges analyzed.

Thanks are due to the midwives of Cantabria health areas III and IV for their assistance in recruiting the pregnant women (Azucena Setien-Rodríguez, Raquel Zubeldia-Valdés, Sonia Ojugas-Zabala, Aranzazu Mouriz-Monleon, Rosa Nuria Secadas-López, Aurora García-Otero, Laura Gutiérrez-Chicote, Cristina Temprano-Marañón and Mercedes Álvarez del Campo). We are grateful to all of them for their collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz Ochoa D, Piedra León M, Lavín Gómez BA, Baamonde Calzada C, García Unzueta MT, Amado Señarís JA. Influencia del estado de yodación sobre la función tiroidea materna durante la gestación. Endocrinol Nutr. 2017;64:331–333.