Viral infections appear to be a factor involved in numerous forms of thyroiditis, characterised by some form of thyroid inflammation, subacute thyroiditis and autoimmune thyroid diseases.1

In December 2019, a coronavirus emerged from the city of Wuhan (China) and caused a pandemic; the virus, named SARS-CoV-2, is capable of causing an acute respiratory distress syndrome known as COVID-19 (COronaVIrus Disease 2019). The virus spread quickly through more than 180 countries, and the number of cases continues to rise around the world.2

We report the case of a patient with thyroiditis in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Case reportA 52-year-old man with a history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus with microalbuminuria, dyslipidaemia, grade 1 obesity and peripheral artery disease was admitted to internal medicine with signs and symptoms of low-grade fever, epigastric pain and nausea. Physical examination revealed fever, bilateral crackles up to the middle fields and hypoxaemia with persistent oxygen saturation levels of 90%–92% with no dyspnoea.

A chest X-ray taken on admission showed bilateral peripheral alveolar infiltrates consistent with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The patient was treated with ritonavir/lopinavir and empirical antibiotic therapy with levofloxacin and ceftriaxone. Two nasopharyngeal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests were negative, and a third PCR test on a sputum sample was positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Due to his elevated inflammatory parameters and persistent hypoxaemia, after the diagnosis was confirmed, he was given a dose of tocilizumab.

Laboratory testing on admission revealed thyroid abnormalities, with elevated thyroxine (1.83 pg/ml [0.93–1.7 pg/ml]), normal triiodothyronine (3.21 pg/ml [1.8–4.6 pg/ml]), suppressed thyrotropin (0.10 pg/ml [0.27–4.2 pg/ml]), as well as negative autoimmunity, with thyroglobulin (Tg) antibodies (Ab) of 1.22 IU/ml (0–4.11), thyroperoxidase (TPO) Ab of 0.89 IU/ml (0–5.61), thyroid-stimulating (TSH) hormone receptor Ab of 0.2 IU/l and thyroxine-binding globulin levels of 21.9 µg/ml (14–31). The following levels were notably elevated: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (58 mm/h [1–15]), C-reactive protein (CRP) (10 mg/dl [0−0.5]), ferritin (394 ng/ml [30–400]), interleukin (IL)-6 (113 ng/l [normal levels <40 ng/l]).

The patient never showed any clinical symptoms consistent with hyperthyroidism. Physical examination did not find any evidence of goitre or neck pain.

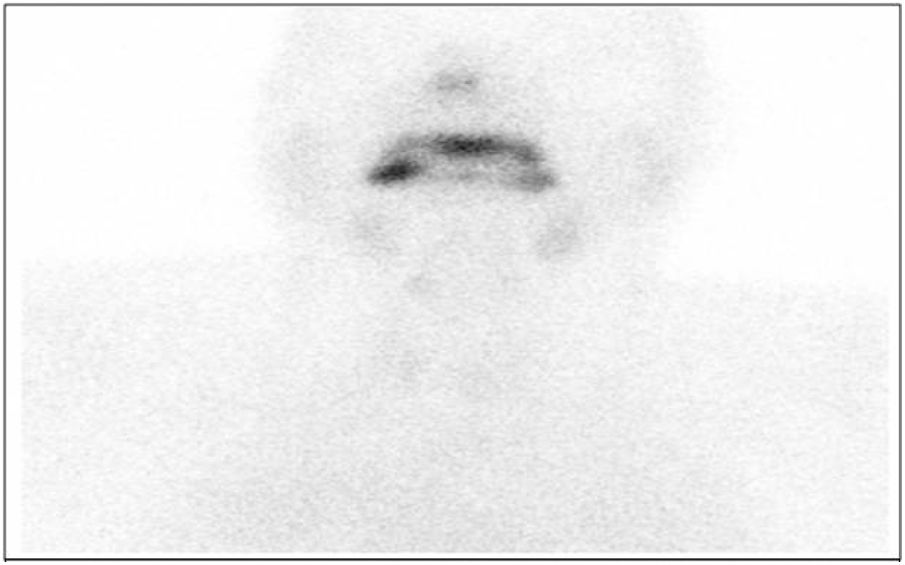

In order to measure the activity of the thyroid gland, thyroid scintigraphy was performed; this showed increased vascular fundus uptake with virtually no thyroid gland activity, suggestive of thyroiditis (Fig. 1).

Based on the patient’s medical history, both prior administration of iodinated contrast and a history of taking amiodarone were ruled out. He denied having a family history of thyroid disease. He had a laboratory test result from March 2018 indicating normal thyroid function, with a thyrotropin level of 0.95 pg/ml (0.27–4.2 pg/ml).

No specific antithyroid treatment was initiated. Empirical treatment with beta blockers (propranolol) was started and later stopped in the absence of symptoms. Follow-up laboratory testing and thyroid ultrasound showed that the patient’s thyroid function had returned to normal, with isoechogenicity throughout the thyroid gland and no signs of thyroiditis.

DiscussionSubacute or De Quervain’s thyroiditis is a self-limiting inflammatory thyroid disorder characterised by neck pain and thyrotoxicosis. The disease exhibits characteristics typical of viral infections, including viral prodrome with myalgia, malaise and fatigue.

One characteristic sign on laboratory testing is an elevated ESR. Typically, plasma thyroid hormone levels are elevated and TSH levels are undetectable with negative TPO and Tg Ab. The leukocyte count is usually normal with increased CRP, IL-6 and ferritin, as seen in the case report. Characteristically, I131 uptake is very low, and thyroid ultrasound shows areas of focal hypoechogenicity.

It seems that after a viral infection, an immune response mediated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes can occur and damage thyroid follicular cells. The onset and recurrence of subacute thyroiditis appear to be associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B35. Hence, the onset of subacute thyroiditis is influenced by genetics, and it appears that it can develop in patients with a genetic predisposition during a viral infection.1

The pathogenesis of this disease is linked to various viruses: enteroviruses, Coxsackieviruses, adenoviruses, orthomyxoviruses, Epstein–Barr virus, hepatitis E virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cytomegalovirus, dengue viruses and rubella virus. However, viral inclusion bodies have not been seen in thyroid tissue.1,3

Silent thyroiditis is a form of autoimmune thyroiditis that co-occurs with thyrotoxicosis caused by the release of thyroid hormones from a non-tender thyroid gland. High titres of TPO and Tg Ab are characteristically detected. The inflammatory process destroys the follicles, resulting in the release of large amounts of T4 and T3 into the bloodstream and causing thyrotoxicosis. The leukocyte count is normal and the ESR may be slightly elevated. During the thyrotoxicosis phase, I131 uptake is decreased.1

Our patient had laboratory results consistent with thyrotoxicosis, with a slightly elevated ESR, a non-tender thyroid gland, no I131 uptake and a negative autoimmunity study; such findings are possible in silent thyroiditis. The patient required no specific treatment as he had no symptoms; hence, it is suspected that he had silent thyrotoxicosis in the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In a study published in 2007, a substantial number of patients with SARS-CoV-1 infection exhibited thyroid function abnormalities. In SARS-CoV-1, there was speculation as to the possibility of the virus itself causing direct damage to the thyroid gland through unclear mechanisms. Examination of thyroid tissue samples found destruction of the follicular and parafollicular epithelium. Another possibility was that the virus caused central hypothyroidism induced by hypophysitis or hypothalamic dysfunction.3,4

To date, a single case of subacute thyroiditis due to SARS-CoV-2 has been reported; that patient, unlike ours, experienced symptoms. The prevalence and diversity of this disease in patients with COVID-19 remains to be determined; larger numbers of cases would be needed to establish its causality and relationship to the virus.3

ConclusionSARS-CoV-2 infection has had a major impact in many countries due to its rapid spread and the large numbers of patients with COVID-19; complications secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection have not yet been established. This article reports the case of a patient with concomitant SARS-CoV-2 infection and thyroiditis.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Barahona San Millán R, Tantinyà Daura M, Hurtado Ganoza A, Recasens Sala M. Tiroiditis indolora en infección por SARS-CoV-2. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:757–758.