There has been a revolution in the treatment of diabetes mellitus in recent years with the introduction of the GLP-1 receptor agonists, among other drugs. Because of the still limited experience with these drugs, clinical practice may reveal previously unreported complications related to the drug substances themselves or to the administration protocol employed, as described below.

An 81-year-old woman reported to the emergency room due to a 10-day history of epigastric pain that worsened after meals. There was no associated fever or changes in bowel habit, though she did suffer nausea without vomiting. Guided questioning revealed no other symptoms. The patient had consulted four times because of these problems (the first visit being on 24 October), with all complementary tests (hematological and liver function parameters, abdominal X-rays and electrocardiogram) yielding normal results. Her personal history comprised cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia under treatment), chronic ischemic heart disease subjected to revascularization in 2011, and persistent atrial fibrillation treated with anticoagulants. Her usual treatment consisted of rivaroxaban 20mg, carvedilol 6.25mg, valsartan 160mg, amlodipine 5mg, furosemide 40mg, atorvastatin 40mg nitroglycerin (NTG) patch 10mg, omeprazole 20mg, vildagliptin 5mg/metformin 1g/12h, insulin Lantus® 16IU and Trulicity (dulaglutide)® 1.5 every 7 days (this drug being started on 21 October 2017).

The physical examination, abdominal X-rays and blood and liver function tests proved normal.

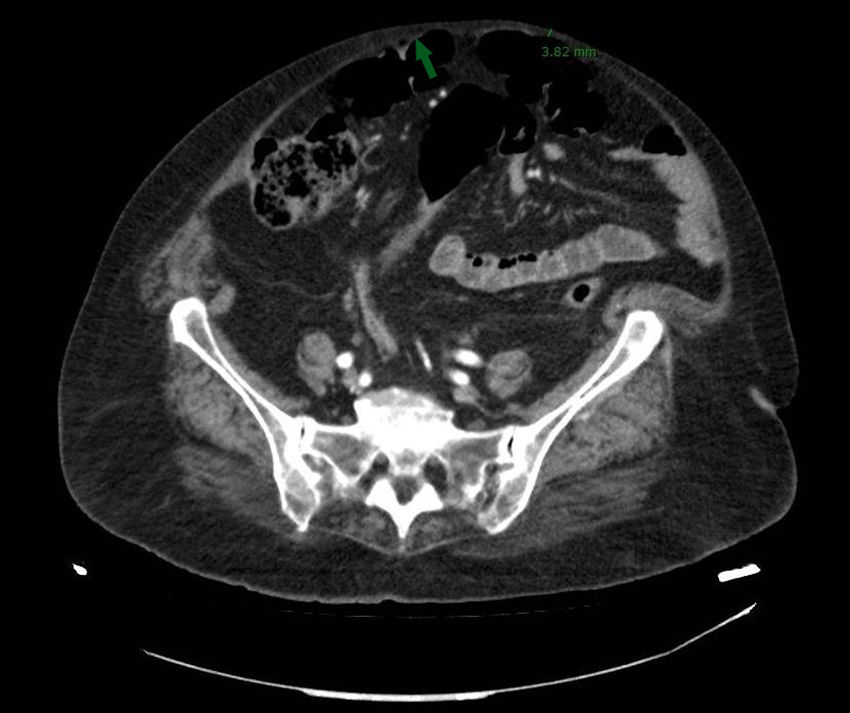

Given the symptoms reported by the patient, an oral endoscopy was performed, with a diagnosis of antral biliary reflux. Computed tomography (CT) with abdominal contrast showed signs of pneumoperitoneum with the presence of bubbles both in the anterior abdominal wall – hollow organ perforation being discarded – and in the subcutaneous cellular tissue of the abdominal wall. This was probably related to subcutaneous injections, since the subcutaneous cellular tissue thickness in the anterior abdominal wall was 5mm, reaching 3.8mm in some zones (Fig. 1).

In view of the imaging findings, a repeat exploration was carried out and the patient was questioned again. Marked abdominal muscle separation (diastasis recti) was noted, becoming visible on the patient being raised. It should also be noted that the patient administered the dulaglutide doses in this abdominal muscle separation zone, the needle of the device being 5mm in length. It was also seen that insulin administration was performed in the proximal region of both lower limbs.

After dulaglutide administration in the abdominal zone was discontinued, the patient was followed-up on in the outpatient clinic one month after hospital discharge, and was seen to be completely asymptomatic. Of note was the absence of abdominal pain.

Gastrointestinal adverse effects such as nausea or vomiting, among other problems, are known, though without reports of their manifestation as seen in our patient. Likewise, the incidence and severity of such effects are less in patients treated on a once-weekly basis.

Many studies have been made in patients treated with GLP1 agonists (dulaglutide), assessing the safety of the administering device1 and reporting adverse effects in the form of bruising, subcutaneous emphysema and pain at the site of drug administration, as well as skin reactions such as rash.2 However, to date there have been no reports of pneumoperitoneum, hollow organ perforation or other serious adverse effects. In our patient, pneumoperitoneum was caused because the drug was injected into an area which was unsuitable due to the extremely thin abdominal wall and muscle diathesis.

The etiology underlying pneumoperitoneum in our patient was established following the exclusion of other possible causes, with confirmation of the extreme thinness of the abdominal wall where the drug was administered, and with the resolution of the condition after its administration in this area was suspended.

A limitation in testing the hypothesis was the impossibility of determining the presence of the drug in the bowel contents, resulting from ineffective administration. This is due to the proteic composition of the drug, which facilitates its digestion and thus precludes its detection through testing.

The characteristics of the abdominal wall of the patient; the injection of the drug into the area presenting muscle diathesis; and the characteristics of the injection device make it reasonable to presume that the cause of the pneumoperitoneum was the administration of the drug.

Diathesis or separation of the abdominal muscles is not uncommon, particularly in obese individuals, in which GLP1 analogs are especially useful for the treatment of diabetes. In our opinion, this circumstance could represent a contraindication to the administration of the drug in the abdominal region. An alternative in this respect could be its administration in other body zones or specific training imparted by the nursing staff, emphasizing the so-called “skin pinch technique”, which raises the skin and its underlying layers – thereby avoiding the risk of bowel loop perforation.

Thanks are due to all the healthcare professionals who collaborated in the preparation of this scientific letter following the diagnosis of the case.

Please cite this article as: Miras I, Ramírez N, Sánchez P, Hernández C, Acosta D. Neumoperitoneo por inyecciones subcutáneas. A propósito de un caso. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:548–549.