Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has increased the life expectancy of patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection to the point that it is now similar to that of the general population.1 The increase in age-associated comorbidities and the need to add treatments have rendered drug interactions a challenge in the management of the therapy. Cobicistat is an inhibitor of the isozyme of the hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) usually employed to enhance drugs used in HIV treatment. Concomitant use of drugs metabolised through this pathway promotes the onset of potentially harmful drug-drug interactions.

Below, we report the clinical case of a 49-year-old man with a personal history of active tobacco use, dyslipidaemia, bronchial asthma, ischaemic heart disease and HIV infection known for more than 10 years. The patient has received various treatments to date. He was initially treated with efavirenz, emtricitabine and tenofovir, with virological failure after a few months. He was then switched to darunavir/ritonavir, raltegravir and etravirine, and this treatment was maintained for five years with an undetectable viral load and decreasing CD4 T lymphocytes. This regimen was subsequently simplified to treatment with darunavir/ritonavir plus raltegravir, and a year before our assessment, he was switched to his current combination with darunavir, cobicistat and raltegravir. In addition to ART, he was on oral treatment with omeprazole, bisoprolol, ramipril, acetylsalicylic acid, ezetimibe and rosuvastatin. His inhaled treatment for bronchial asthma consisted of on-demand salbutamol, fluticasone 500 µg and salmeterol 50 µg every 12 h, which had required an increase to a maximum dose around five months earlier due to poor disease control.

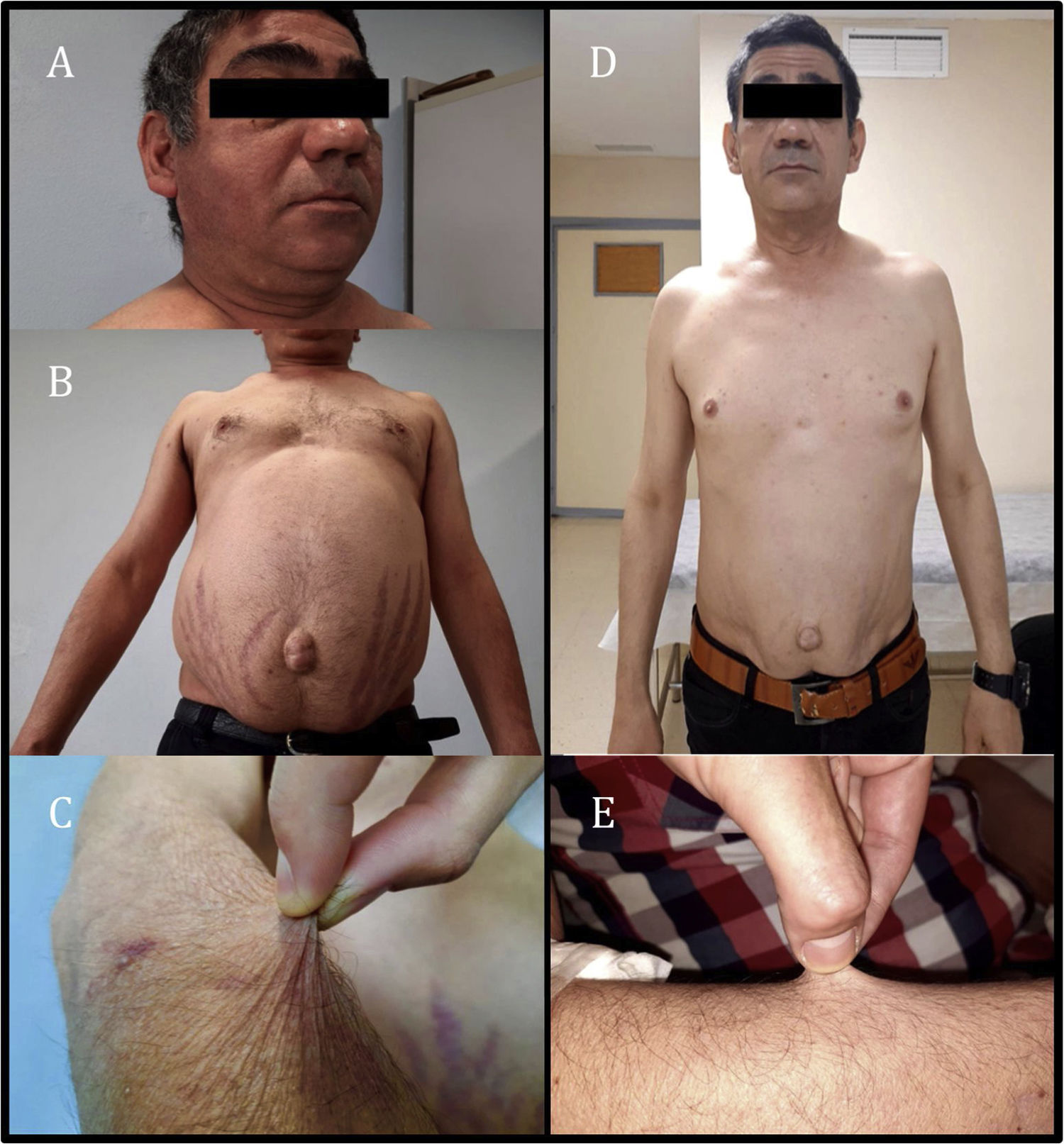

The patient was assessed as he exhibited asthenia, worse exercise tolerance and increased abdominal fat with red striae in that location, accompanied by thinning of the limbs and easy bruising for the past month and a half. Physical examination revealed the patient to have a weight of 74.9 kg, a body mass index of 24.73 kg/m2, blood pressure of 113/71 mmHg, moon face with increased bilateral supraclavicular fat (Fig. 1A), abdominal obesity with a periumbilical predominance and red-wine striae around 3 cm thick (Fig. 1B), skin atrophy and thinning of the limbs with healing bruises (Fig. 1C). Complementary tests showed adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) below 2 pg/mL (normal range 10–46 pg/ml) and baseline plasma cortisol 0.4 µg/dl (normal range 7−25 µg/dl), in addition to abnormal baseline blood glucose (114 mg/dl).

Given the clinical findings of Cushing's syndrome and laboratory findings of suppressed ACTH and cortisol, iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome was suspected. After administration of glucocorticoids by other routes was ruled out, only exposure to inhaled fluticasone was observed. Adrenal axis suppression is reported in 20.5% of patients receiving inhaled corticosteroids. Furthermore, some studies have suggested that adrenal axis suppression is subject to individual variability in glucocorticoid action and metabolism, including CYP3A4 activity, which is the main route of inactivation of most prescription glucocorticoids.2 The drugs the patient was receiving included cobicistat, a powerful inhibitor of this metabolic pathway. As an interaction between fluticasone and cobicistat was suspected, both drugs were suspended, beclometasone was started and the patient's ART was switched to bictegravir, emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide. After two months, the Cushingoid appearance described was seen to have virtually resolved (Fig. 1D and E), the patient had lost 8 kg and his blood glucose levels had returned to normal. Hormone testing showed ACTH 52 pg/mL and baseline plasma cortisol 5.6 µg/dl; therefore, a short stimulation test was performed with 250 μg of ACTH, yielding a peak plasma cortisol level of 8.49 µg/dl. The clinical and laboratory changes observed following suspension of both drugs led to the diagnosis of iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome secondary to interaction between fluticasone and cobicistat and subsequent tertiary adrenal insufficiency due to adrenal axis suppression. Replacement therapy was started with Hidroaltesona (hydrocortisone) 30 mg/day, and recommendations on the use of glucocorticoids in the event of surgery or intercurrent disease were provided.

Inhaled corticosteroids, such as budesonide, ciclesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone, mometasone and triamcinolone, are CYP3A4 substrates, and therefore have the potential to interact with inhibitors of this cytochrome such as ritonavir and cobicistat. These interactions result in increased exogenous corticosteroid exposure with a risk of developing Cushing's syndrome and adrenal suppression.3 Beclometasone, despite also being a CYP3A4 substrate, is mainly hydrolysed by esterases and has low affinity for the glucocorticoid receptor, as well as a short half-life; hence, it should be considered an option in these patients.4 There are published cases of iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome secondary to interaction between cobicistat and ritonavir with oral and inhaled corticosteroids.5,6 A series of 139 cases found that inhaled fluticasone was involved in 20.1% of these cases.7

The case reported highlights the importance of drug-drug interactions with the use of CYP3A4 inhibitors. Powerful CYP3A4 substrate steroids, such as fluticasone, budesonide and triamcinolone, should ideally not be prescribed to patients on treatment with inhibitors of this pathway. If this is unavoidable in the case of a patient with HIV, it is advisable to use alternative ART combinations not including cobicistat or ritonavir before introducing steroids. If this is still not possible, the patient should be monitored closely in the two to three subsequent months, given the possibility of the patient developing iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome like that reported, and specific algorithms for its management should be used.8

Please cite this article as: Santaella Gómez A, Amaya García MJ, Saponi Cortés JMR, Martín Ruiz C. Síndrome de Cushing secundario a fluticasona inhalada. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2022;69:442–444.