The aim of this study was to describe therapeutic education programmes in diabetes in Catalonia and the differences according to the healthcare setting in which the patients are attended (primary care [PC] and specialised diabetes care [SDC]).

MethodWe performed a descriptive, cross-sectional, comparative study of diabetes nurses (DN) in SDC and PC in Catalonia. The sample was obtained from all the DN in SDC and a randomised cluster sample of DN in PC. The questionnaire of the Study of European Nurses in Diabetes (SEND) validated in Spanish was used.

ResultsA total of 287 questionnaires were analysed (24.3% SDC and 75.6% PC). More training in diabetes through masters, postgraduate courses and continuing education was observed in SDC (p<0.001) as well as structured, written, education programmes and the combination of individual and group education strategies (p<0.05). The roles of educator, consultant, researcher, manager, liaison or collaborator and innovator and the telematic follow-up of patients was also more developed in SDC (p<0.05). The grade of work satisfaction was elevated in both groups.

Conclusions(1) Nursing professionals in SDC assume more roles of specialised clinical nursing and also have more training in diabetes and therapeutic education than PC professionals. (2) Professionals in SDC work with a greater proportion of structured diabetes therapeutic education programmes although this should improve in both settings. According to the results obtained and the scientific evidence currently available, the training of DN working in the care of people with diabetes should be accredited in order to increase the use of structured programmes and investigation by DNs in both healthcare settings.

Describir la educación terapéutica en diabetes en Cataluña y las diferencias según el ámbito asistencial donde esta se imparte (asistencia primaria [AP] y asistencia especializada [AE]).

MétodoEstudio descriptivo, transversal y comparativo en PE de AE y de AP en Cataluña. La muestra se obtuvo a partir de todos los PE de AE y una muestra aleatoria por conglomerados de PE de AP. Se utilizó el cuestionario del Study of European Nurses in Diabetes validado al español.

ResultadosSe analizaron 287 cuestionarios (24,3% AE y 75,6% AP). Se observó más formación en diabetes a nivel de máster, posgrado y formación continuada en AE (p<0,001). Más programas de educación estructurada, escritos y que combinan las estrategias de educación individual y grupal en AE (p < 0,05). Los roles educador, asesor, investigador, director, colaborador e innovador así como el seguimiento de pacientes vía telemática están más desarrollados en AE (p<0,05). En ambos grupos el grado de satisfacción laboral es elevado.

Conclusiones1) Los profesionales de enfermería de AE asumen más roles de enfermera clínica especialista, además de tener más formación en diabetes y educación terapéutica que los profesionales de AP. 2) En AE se trabaja en mayor proporción con programas de ETD estructurados pero en ambos ámbitos se debería mejorar. De acuerdo con los resultados obtenidos y la evidencia científica disponible sería necesario acreditar la formación de los PE que trabajan en la atención de personas con diabetes, aumentar la utilización de programas estructurados y la investigación propia en ambos ámbitos de asistencia.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a clear example of a chronic disease requiring complex treatment. It has been reported that 98% of the actions carried out in correct management of diabetes are made by the patient and/or family members,1 and treatment success depends on the knowledge, capacity and skills of the patient or relative in adopting the necessary self-care. Therefore, continuing therapeutic education (TE) adapted to the needs of each patient is essential for both the patient and the family.2 It has been demonstrated that TE is more effective if it is integrated in the treatment through structured TE programmes carried out by expert professionals.3,4

The figure of nurses in both primary care (PC) and specialised diabetes care (SDC) is one of the key components of the treatment of DM and their role is determinant in the education of patients, relatives and the community as well as for the development of more effective healthcare systems.5 In order to provide quality TE, it is fundamental for professionals to receive specific training. This training should be based not only on biomedical knowledge but also on communication skills, the use of paedagogic techniques and the planning of educational programmes, and it should be a requisite in the curricular profile for working in this setting.6

Scientific societies in the United States and Canada and in some European countries have elaborated a framework of different levels of competence for diabetes nurses (DN) acquired by specific training corresponding to that of a specialised clinical nurse or advanced practice nurse (APN).7 However, the role of specialised diabetes nurses (DSN) differs from country to country.7

Several studies have shown that advanced practice of nursing professionals is obtained by the acquisition of a series of competences integrated within a wide variety of subroles rather than within specific functions. The most important subroles described are8,9:

- -

The role of expert practice: provides direct care to patients and indirect care by collaborating with other members of the team or by participating in the elaboration of educational programmes, adjusting treatment or requesting complementary tests.

- -

Role of educator: educates patients, relatives and the general public.

- -

Role of consultant: is a reference for patients, relatives, other professionals and the institution itself.

- -

Role of researcher: participates in research projects as the principal investigator or as a collaborator.

- -

Role of manager or director: participates in the administrative or economic management of diabetes care and in the planning of educational programmes as well as in the identification of shortcoming in diabetes care.

- -

Role of collaborator or liaison: coordinates resources and services for diabetes care and the relationship between teams and healthcare levels.

- -

Role of innovator: detects and evaluates needs for change and implements new healthcare models.

Many of these roles overlap with those of general nurses or PC and the debate lies in clarifying the roles and competences of the different collectives for professional development. However, this remains to be solved and leads to conflict or ambiguity of roles.10 Despite these controversies, it has been suggested that the influence of APN in a determined area has shown significant improvements in the quality of care, patient safety, a reduction in emergency department admissions as well as a reduction in healthcare costs.11,12

In 2014, the Spanish Society of Diabetes (SED) developed a position statement related to the curricular profile of DSN13 recommending that they should have obtained accredited training in biomedicine, chronicity and TE, management and investigation according to proposals by the main scientific societies. This training is acquired with an official master based on the care and education of people with diabetes given since 2016 by the University of Barcelona.14 This master covers the training needs of DSN, although in many healthcare centres this type of training has no curricular value for working in the care of people with DM.

The substudy of the Study of European Nurses in Diabetes (SEND)15 carried out in Spain analysed the professional profile of nurses in PC and in specialised care based on the 7 roles mentioned above and demonstrated that specialised care more frequently assumes the roles corresponding to APN. However, there are no data in Catalonia on how TE in diabetes (TED) is developed and the professional profile of the DN in SDC and PC. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to describe the TED in Catalonia and the differences according to the healthcare setting in which this programme is carried out (PC and SDC).

Material and methodWe performed a cross-sectional study carried out from September 2014 to September 2015 in Catalonia. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Clinical Investigation of the Hospital Universitario Mútua Terrassa.

Study population: Nurses devoted to TED in patients with diabetes attended within the settings of SDC and PC.

Inclusion criteria: DN in hospital Endocrinology and Diabetes Units and DN in PC attending patients with diabetes who accept to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria: Nurses whose professional activity does not include the care of people with diabetes. Paediatric nurses in PC centres were excluded since paediatric type 1 diabetes (T1D) is controlled in Endocrinology Units of paediatric hospitals. Nurses working in management who do not carry out healthcare activities and nurses specialised in obstetrics were also excluded from the study.

Sample selectionSpecialised care included all professionals dedicated to TED in hospitals with Endocrinology Units.

Primary care: a cluster sample was made. Each cluster represented a basic healthcare area (BHCA). Ninety-seven of the 364 BHCA in Catalonia in 2014 were randomly selected for the study. In a second stage we collected information from the professionals dedicated to TED in these centres. Taking into account the impossibility of obtaining a list of all the professionals who could potentially be included in the study (nurses attending patients with diabetes), and after studying the results of the first pilot samples, for each BHCA we estimated that three professionals from each centre should be included in the study. On completion of data collection, the weight of the sampling design and the response obtained from each centre was recalculated including the final database for use in posterior data analyses.

For data collection, the Spanish version of the questionnaire used in the SEND study was adapted and validated. This questionnaire is made up of 39 questions related to demographic variables as well as variables related to training in diabetes, workload, services to patients and relatives, evaluation and registry of healthcare data and the degree of work satisfaction. The questionnaire also evaluates the 7 types of professionals roles of an APN: expert practice, educator, consultant, researcher, manager/director, collaborator or liaison, and innovator.

The questionnaire was sent to nurses in the Departments of Endocrinology and Nutrition of the hospitals and the BHCAs selected. A reminder about the questionnaire was made at 2 and 6 months in the centres in which no response had been obtained.

Statistical analysis: Descriptive analysis of the variables of interest was made using frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables and means and standard deviations (SD) for quantitative variables and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Taking into account the complex design of the sample, the descriptive statistics were weighted and non-weighted to demonstrate the characteristics of the sample collected and the correction of the estimations due to the effect of the design.

The data of the SDC and PC were compared using the Rao-Scott Chi square test (correction for complex design) for qualitative variables, and the Student's t test and ANOVA were used for quantitative variables. Linear regression and multivariate logistic regression models were adjusted to analyse possible associations among explicative variables and the resulting variables of interest, obtaining adjusted effects and the corresponding odds ratio (OR). To study the association between the degree of work satisfaction and determined characteristics of the professionals and work centres, a new variable of “total satisfaction” was first constructed as the sum of the scores of each of the 16 items of satisfaction in the questionnaire. Afterwards, the principal components were analysed to reduce the number of variables of satisfaction. This allowed grouping the items into 5 groups, calculating 5 variables of satisfaction as the mean of the scores of the corresponding items. Finally, the multiple linear regression models were adjusted. Possible effects of interaction were controlled in all the multivariate models of the study. The data analyses were performed using the complex sample module of the SPSS v24.

ResultsParticipantsA total of 287 questionnaires were collected. In the 46 hospitals with an Endocrinology Unit there were 77 DN dedicated to TED, with 70 (91%) responding to the questionnaire. Of the 97 PC centres included in the cluster sampling, 217 professionals responded. The distribution by provinces and healthcare setting was: 198 (68.9%) corresponded to the province of Barcelona (66.2% from PC and 87.4% SDC), 39 (13.5%) were from the province of Tarragona (15% from PC and 9.4% from SDC), 18 (6.2%) corresponded to the province of Lérida (7.9% from PC and1.6% from SDC) and 32 (11.1%) were from the province of Gerona (11.5% from PC and 1.6% from SDC).

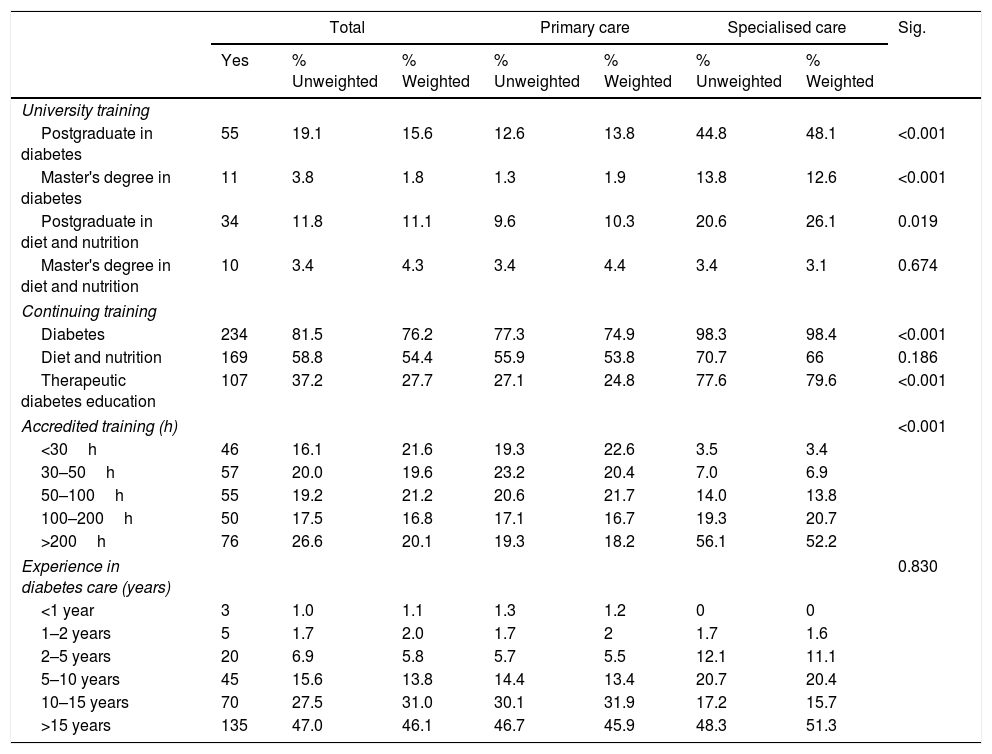

The mean age of the professionals was 47.3±9.16 years; 94% were women and 96.5% had a degree in nursing. Table 1 shows the training and experience in diabetes of the participants according to the different healthcare settings.

Training and experience in diabetes by areas of assistance.

| Total | Primary care | Specialised care | Sig. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | % Unweighted | % Weighted | % Unweighted | % Weighted | % Unweighted | % Weighted | ||

| University training | ||||||||

| Postgraduate in diabetes | 55 | 19.1 | 15.6 | 12.6 | 13.8 | 44.8 | 48.1 | <0.001 |

| Master's degree in diabetes | 11 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 13.8 | 12.6 | <0.001 |

| Postgraduate in diet and nutrition | 34 | 11.8 | 11.1 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 20.6 | 26.1 | 0.019 |

| Master's degree in diet and nutrition | 10 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 0.674 |

| Continuing training | ||||||||

| Diabetes | 234 | 81.5 | 76.2 | 77.3 | 74.9 | 98.3 | 98.4 | <0.001 |

| Diet and nutrition | 169 | 58.8 | 54.4 | 55.9 | 53.8 | 70.7 | 66 | 0.186 |

| Therapeutic diabetes education | 107 | 37.2 | 27.7 | 27.1 | 24.8 | 77.6 | 79.6 | <0.001 |

| Accredited training (h) | <0.001 | |||||||

| <30h | 46 | 16.1 | 21.6 | 19.3 | 22.6 | 3.5 | 3.4 | |

| 30–50h | 57 | 20.0 | 19.6 | 23.2 | 20.4 | 7.0 | 6.9 | |

| 50–100h | 55 | 19.2 | 21.2 | 20.6 | 21.7 | 14.0 | 13.8 | |

| 100–200h | 50 | 17.5 | 16.8 | 17.1 | 16.7 | 19.3 | 20.7 | |

| >200h | 76 | 26.6 | 20.1 | 19.3 | 18.2 | 56.1 | 52.2 | |

| Experience in diabetes care (years) | 0.830 | |||||||

| <1 year | 3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1–2 years | 5 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 2 | 1.7 | 1.6 | |

| 2–5 years | 20 | 6.9 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 12.1 | 11.1 | |

| 5–10 years | 45 | 15.6 | 13.8 | 14.4 | 13.4 | 20.7 | 20.4 | |

| 10–15 years | 70 | 27.5 | 31.0 | 30.1 | 31.9 | 17.2 | 15.7 | |

| >15 years | 135 | 47.0 | 46.1 | 46.7 | 45.9 | 48.3 | 51.3 | |

A mean of 62.32±7.03 patients with diabetes were attended by DN monthly, with significant differences between the two healthcare settings (159.42 patients in SDC vs. 56.66 in PC; p<0.001). Significant differences were also observed in the type of diabetes and the age of the patients. More patients with T1D, gestational DM and other forms of diabetes were attended in SDC, while PC centres more frequently attended patients with type 2 DM (T2D) (p<0.001). In PC, 57.54% of the patients attended were over the age of 65 while only 28.31% (p<0.001) of patients of this age were seen in SDC. According to 24.1% of the professionals in SDC and 17.5% of those in PC, 10–20% of the patients presented language barriers, with no significant differences between the two levels of healthcare.

Relationship or collaboration with other professionalsIt was estimated that the professional relationships and interdisciplinary work are basically found within the same healthcare setting. Thus, SDC professionals mainly collaborated with each other and the endocrinologists (82.7% and 96.9%, respectively), while in PC they collaborate with each other and the general practitioners (81.6% and 96.3%, respectively). Of note was the poor coordination between the different healthcare levels, with only 23.2% of the professionals in PC reporting having coordination programmes with SDC while 41.3% of the professionals in SDC reported coordination with PC (p<0.001).

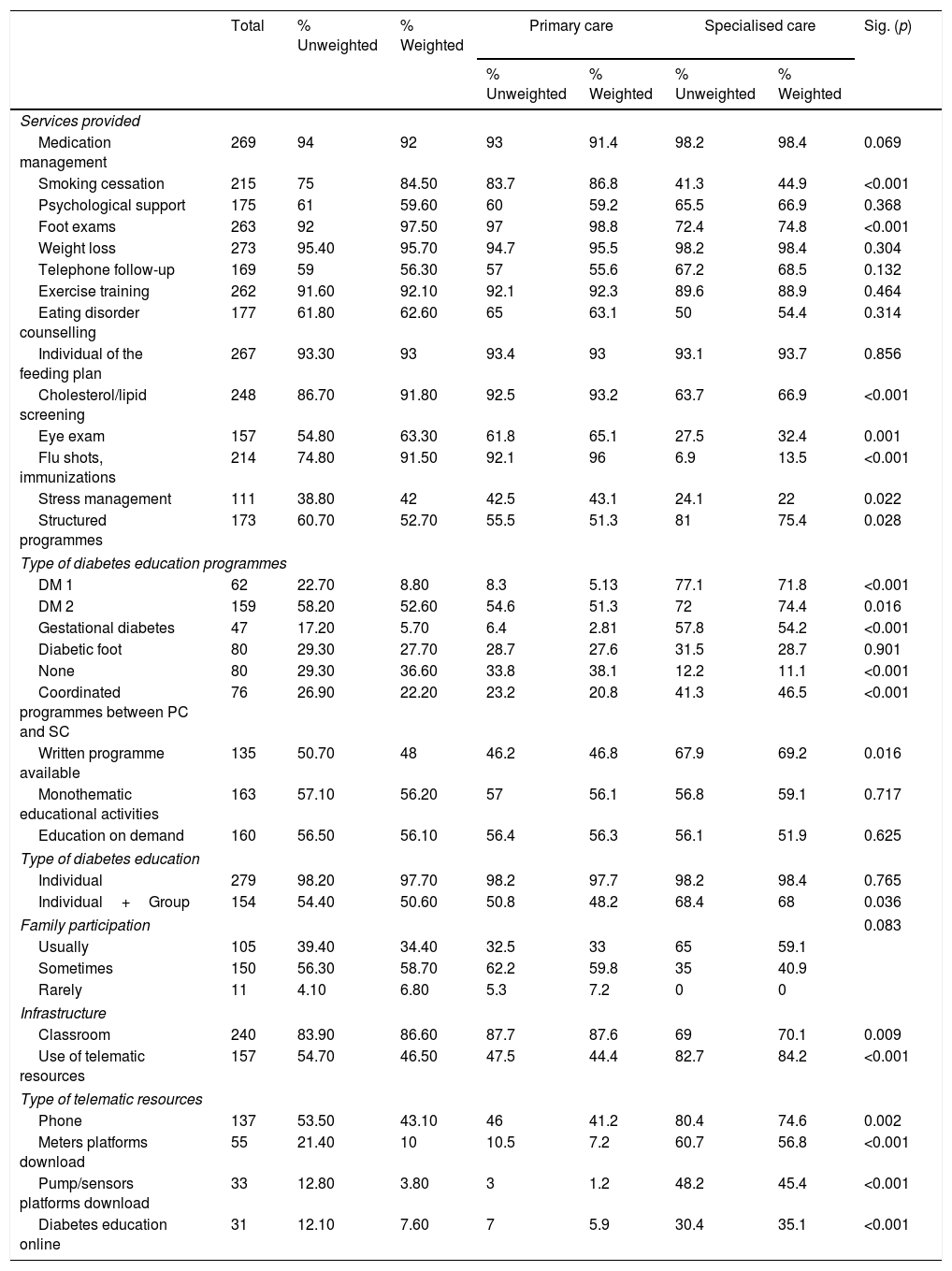

Services, resources, structure and type of therapeutic education providedMore structured education is provided by SDC mainly through programmes aimed at T1D, T2D and gestational DM (75.4% in SDC vs. 51.3% in PC, p=0.028).

The compentences of smoking cessation, feet examination, control of dyslipidemia, ophthalmologic examination, stress management and monitoring of the vaccine calendar are more frequently implemented in PC.

The use of telemedicine platforms for glucose measurement was greater in SDC (OR=16.95, p<0.001). Likewise, the use of continuous subcutaneous insulin pumps or integrated systems (pump sensor) was associated with greater academic training in diabetes (master/postgraduate degree) (OR=6.217, p<0.001), more hours of accredited training (courses, seminars) (OR=2.729, p=0.040) and work in SDC (OR=5.95, p<0.001). Indeed, significant interaction was detected between the healthcare setting, academic training and the hours of accredited training, showing that the greater the number of hours of accredited training, the greater the use of these platforms in SDC compared to PC.

More individual and group education strategies are combined in SDC than in PC (68% vs. 48.2%, p=0.036), although the nurses in PC reported having more infrastructure such as the availability of an adequate classroom with easy access (87.6% in PC vs. 70.1% in SDC, p=0.009). Longer experience in the care of people with diabetes (OR=1–318; p=0.018), more training in diabetes (OR=3.521, p<0.001) and more infrastructure (specific room for therapeutic education) (OR=5758, p=0.004) were associated with greater application of group TED.

Compared to DN in PC, DN in SDC reported having published scientific articles on the results of educational interventions (9.2% vs. 34.4%, respectively; p<0.001). The capacity to investigate and publish scientific articles was significantly associated with working in SDC (OR=6.452; p=0.002), years of experience in diabetes (OR=1.711, p=0.006) and having a specific classroom for carrying out therapeutic education (OR=32.276, p=0.002). Table 2 shows the services, structure and resources available globally and by healthcare setting.

Services, structure and resources available globally and by healthcare setting.

| Total | % Unweighted | % Weighted | Primary care | Specialised care | Sig. (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Unweighted | % Weighted | % Unweighted | % Weighted | |||||

| Services provided | ||||||||

| Medication management | 269 | 94 | 92 | 93 | 91.4 | 98.2 | 98.4 | 0.069 |

| Smoking cessation | 215 | 75 | 84.50 | 83.7 | 86.8 | 41.3 | 44.9 | <0.001 |

| Psychological support | 175 | 61 | 59.60 | 60 | 59.2 | 65.5 | 66.9 | 0.368 |

| Foot exams | 263 | 92 | 97.50 | 97 | 98.8 | 72.4 | 74.8 | <0.001 |

| Weight loss | 273 | 95.40 | 95.70 | 94.7 | 95.5 | 98.2 | 98.4 | 0.304 |

| Telephone follow-up | 169 | 59 | 56.30 | 57 | 55.6 | 67.2 | 68.5 | 0.132 |

| Exercise training | 262 | 91.60 | 92.10 | 92.1 | 92.3 | 89.6 | 88.9 | 0.464 |

| Eating disorder counselling | 177 | 61.80 | 62.60 | 65 | 63.1 | 50 | 54.4 | 0.314 |

| Individual of the feeding plan | 267 | 93.30 | 93 | 93.4 | 93 | 93.1 | 93.7 | 0.856 |

| Cholesterol/lipid screening | 248 | 86.70 | 91.80 | 92.5 | 93.2 | 63.7 | 66.9 | <0.001 |

| Eye exam | 157 | 54.80 | 63.30 | 61.8 | 65.1 | 27.5 | 32.4 | 0.001 |

| Flu shots, immunizations | 214 | 74.80 | 91.50 | 92.1 | 96 | 6.9 | 13.5 | <0.001 |

| Stress management | 111 | 38.80 | 42 | 42.5 | 43.1 | 24.1 | 22 | 0.022 |

| Structured programmes | 173 | 60.70 | 52.70 | 55.5 | 51.3 | 81 | 75.4 | 0.028 |

| Type of diabetes education programmes | ||||||||

| DM 1 | 62 | 22.70 | 8.80 | 8.3 | 5.13 | 77.1 | 71.8 | <0.001 |

| DM 2 | 159 | 58.20 | 52.60 | 54.6 | 51.3 | 72 | 74.4 | 0.016 |

| Gestational diabetes | 47 | 17.20 | 5.70 | 6.4 | 2.81 | 57.8 | 54.2 | <0.001 |

| Diabetic foot | 80 | 29.30 | 27.70 | 28.7 | 27.6 | 31.5 | 28.7 | 0.901 |

| None | 80 | 29.30 | 36.60 | 33.8 | 38.1 | 12.2 | 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Coordinated programmes between PC and SC | 76 | 26.90 | 22.20 | 23.2 | 20.8 | 41.3 | 46.5 | <0.001 |

| Written programme available | 135 | 50.70 | 48 | 46.2 | 46.8 | 67.9 | 69.2 | 0.016 |

| Monothematic educational activities | 163 | 57.10 | 56.20 | 57 | 56.1 | 56.8 | 59.1 | 0.717 |

| Education on demand | 160 | 56.50 | 56.10 | 56.4 | 56.3 | 56.1 | 51.9 | 0.625 |

| Type of diabetes education | ||||||||

| Individual | 279 | 98.20 | 97.70 | 98.2 | 97.7 | 98.2 | 98.4 | 0.765 |

| Individual+Group | 154 | 54.40 | 50.60 | 50.8 | 48.2 | 68.4 | 68 | 0.036 |

| Family participation | 0.083 | |||||||

| Usually | 105 | 39.40 | 34.40 | 32.5 | 33 | 65 | 59.1 | |

| Sometimes | 150 | 56.30 | 58.70 | 62.2 | 59.8 | 35 | 40.9 | |

| Rarely | 11 | 4.10 | 6.80 | 5.3 | 7.2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Infrastructure | ||||||||

| Classroom | 240 | 83.90 | 86.60 | 87.7 | 87.6 | 69 | 70.1 | 0.009 |

| Use of telematic resources | 157 | 54.70 | 46.50 | 47.5 | 44.4 | 82.7 | 84.2 | <0.001 |

| Type of telematic resources | ||||||||

| Phone | 137 | 53.50 | 43.10 | 46 | 41.2 | 80.4 | 74.6 | 0.002 |

| Meters platforms download | 55 | 21.40 | 10 | 10.5 | 7.2 | 60.7 | 56.8 | <0.001 |

| Pump/sensors platforms download | 33 | 12.80 | 3.80 | 3 | 1.2 | 48.2 | 45.4 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes education online | 31 | 12.10 | 7.60 | 7 | 5.9 | 30.4 | 35.1 | <0.001 |

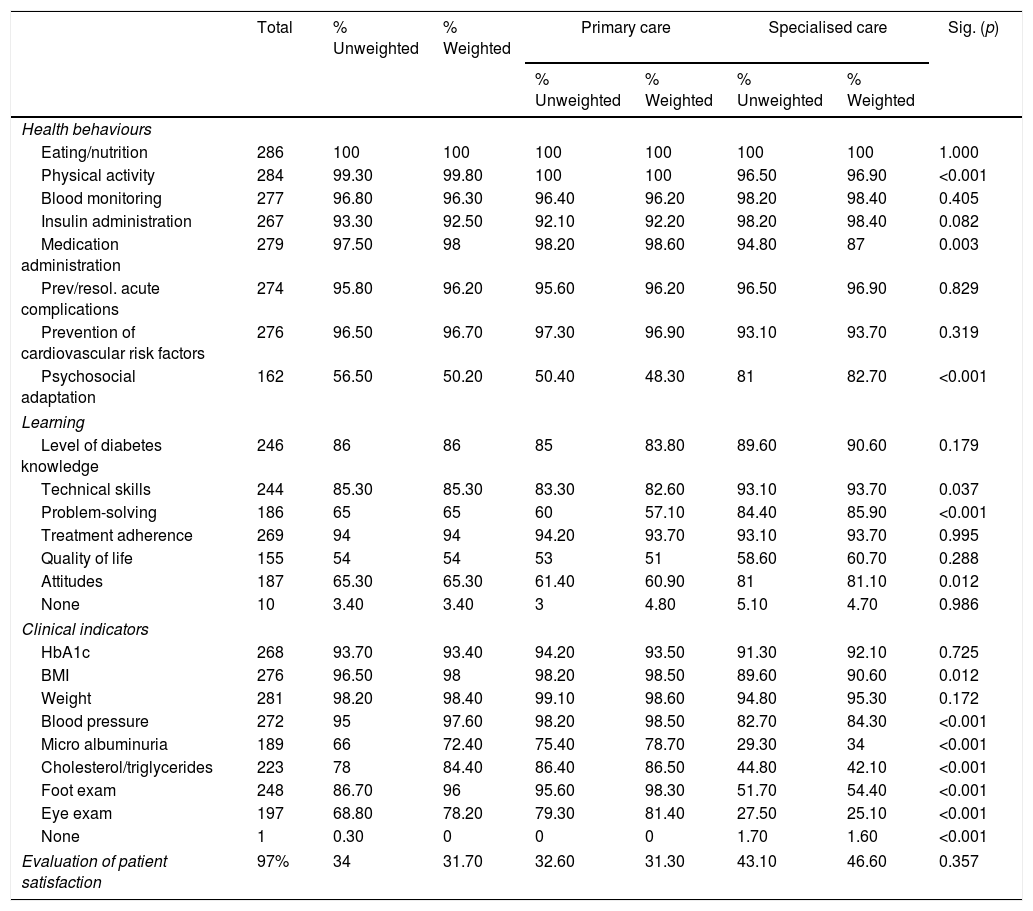

Table 3 shows the results of healthcare behaviours, learning and those of clinical practice which were systematically evaluated at least once a year in the patients attended.

Behavioural outcomes evaluated and systematically collected (at least annually).

| Total | % Unweighted | % Weighted | Primary care | Specialised care | Sig. (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Unweighted | % Weighted | % Unweighted | % Weighted | |||||

| Health behaviours | ||||||||

| Eating/nutrition | 286 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.000 |

| Physical activity | 284 | 99.30 | 99.80 | 100 | 100 | 96.50 | 96.90 | <0.001 |

| Blood monitoring | 277 | 96.80 | 96.30 | 96.40 | 96.20 | 98.20 | 98.40 | 0.405 |

| Insulin administration | 267 | 93.30 | 92.50 | 92.10 | 92.20 | 98.20 | 98.40 | 0.082 |

| Medication administration | 279 | 97.50 | 98 | 98.20 | 98.60 | 94.80 | 87 | 0.003 |

| Prev/resol. acute complications | 274 | 95.80 | 96.20 | 95.60 | 96.20 | 96.50 | 96.90 | 0.829 |

| Prevention of cardiovascular risk factors | 276 | 96.50 | 96.70 | 97.30 | 96.90 | 93.10 | 93.70 | 0.319 |

| Psychosocial adaptation | 162 | 56.50 | 50.20 | 50.40 | 48.30 | 81 | 82.70 | <0.001 |

| Learning | ||||||||

| Level of diabetes knowledge | 246 | 86 | 86 | 85 | 83.80 | 89.60 | 90.60 | 0.179 |

| Technical skills | 244 | 85.30 | 85.30 | 83.30 | 82.60 | 93.10 | 93.70 | 0.037 |

| Problem-solving | 186 | 65 | 65 | 60 | 57.10 | 84.40 | 85.90 | <0.001 |

| Treatment adherence | 269 | 94 | 94 | 94.20 | 93.70 | 93.10 | 93.70 | 0.995 |

| Quality of life | 155 | 54 | 54 | 53 | 51 | 58.60 | 60.70 | 0.288 |

| Attitudes | 187 | 65.30 | 65.30 | 61.40 | 60.90 | 81 | 81.10 | 0.012 |

| None | 10 | 3.40 | 3.40 | 3 | 4.80 | 5.10 | 4.70 | 0.986 |

| Clinical indicators | ||||||||

| HbA1c | 268 | 93.70 | 93.40 | 94.20 | 93.50 | 91.30 | 92.10 | 0.725 |

| BMI | 276 | 96.50 | 98 | 98.20 | 98.50 | 89.60 | 90.60 | 0.012 |

| Weight | 281 | 98.20 | 98.40 | 99.10 | 98.60 | 94.80 | 95.30 | 0.172 |

| Blood pressure | 272 | 95 | 97.60 | 98.20 | 98.50 | 82.70 | 84.30 | <0.001 |

| Micro albuminuria | 189 | 66 | 72.40 | 75.40 | 78.70 | 29.30 | 34 | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol/triglycerides | 223 | 78 | 84.40 | 86.40 | 86.50 | 44.80 | 42.10 | <0.001 |

| Foot exam | 248 | 86.70 | 96 | 95.60 | 98.30 | 51.70 | 54.40 | <0.001 |

| Eye exam | 197 | 68.80 | 78.20 | 79.30 | 81.40 | 27.50 | 25.10 | <0.001 |

| None | 1 | 0.30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.70 | 1.60 | <0.001 |

| Evaluation of patient satisfaction | 97% | 34 | 31.70 | 32.60 | 31.30 | 43.10 | 46.60 | 0.357 |

Significant differences were observed between the two healthcare settings in the evaluation of healthcare behaviours. In PC, aspects related to physical activity and medication management were more frequently evaluated, while in SDC psychosocial adaptation and problem-solving were more frequently assessed.

With regard to learning results, it was of note that in SDC technical skills (93.7% vs. 82.6%, p=0.037), the capacity of problem solving (85.9% vs. 57.1%, p<0.001) and attitudes (81.1% vs. 60.9%, p=0.012) were significantly more frequently evaluated. On the contrary, clinical indicators such as body mass index, cholesterol, triglycerides, and data of foot and ophthalmologic examination were significantly more frequently reported in PC (p<0.001).

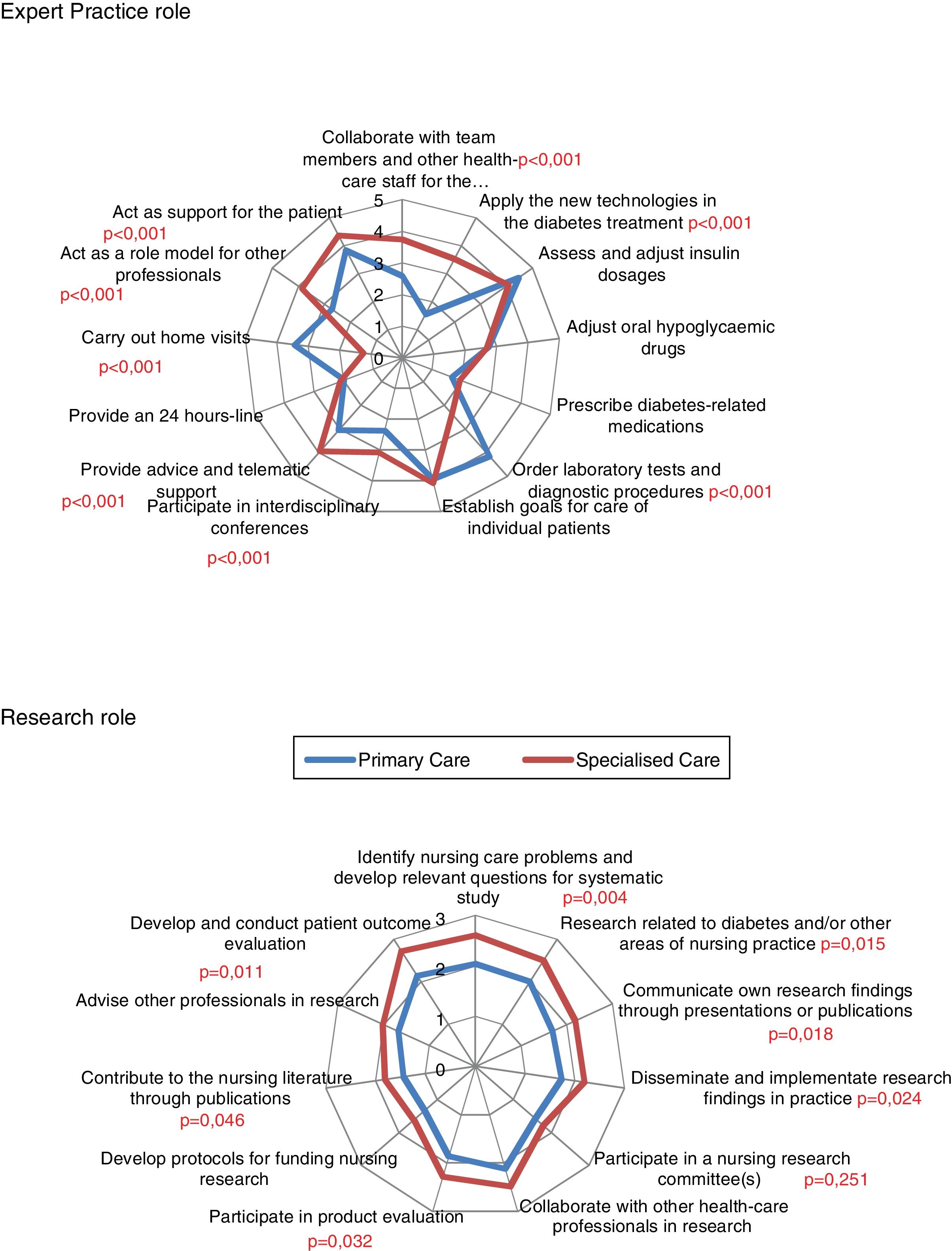

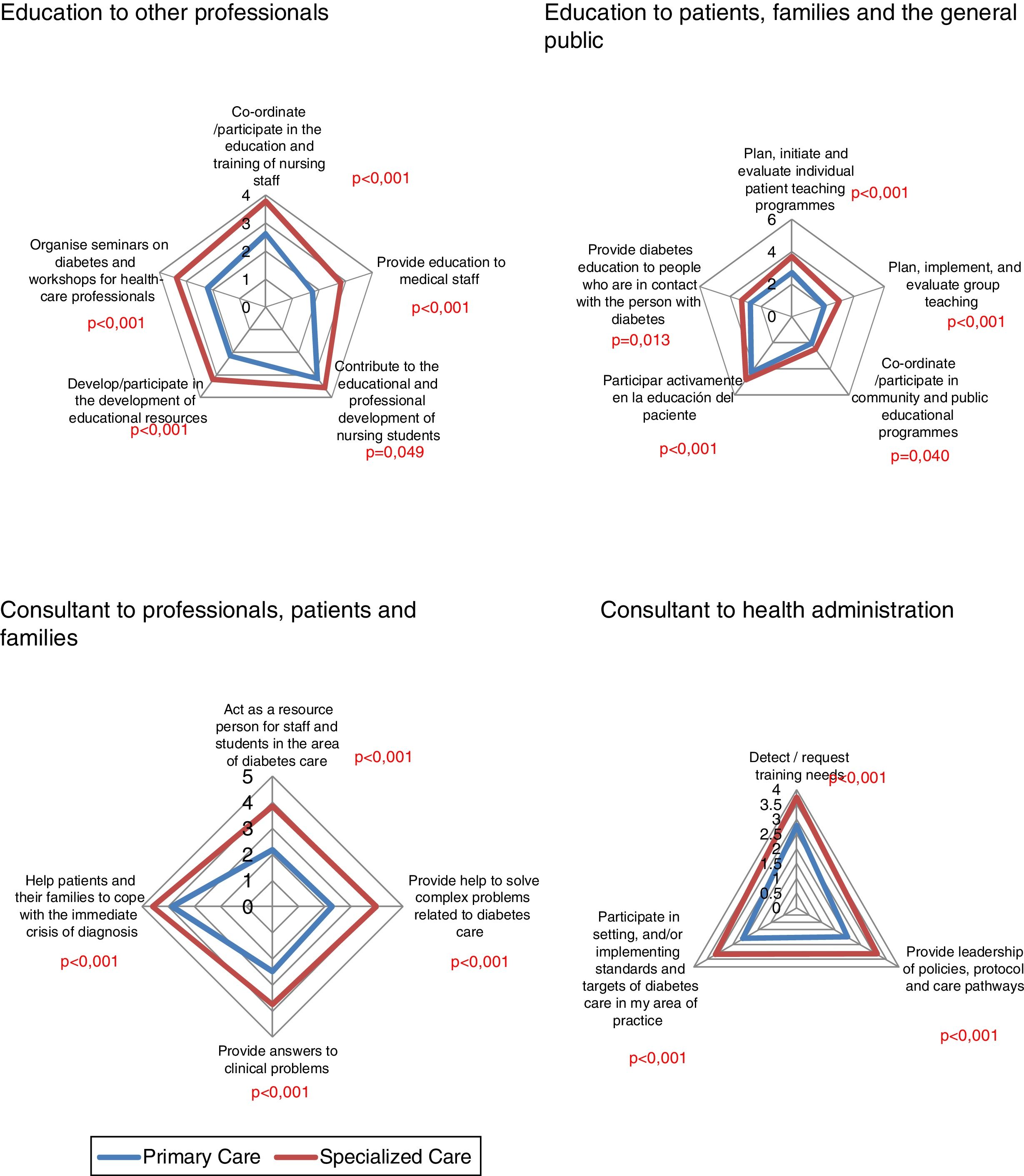

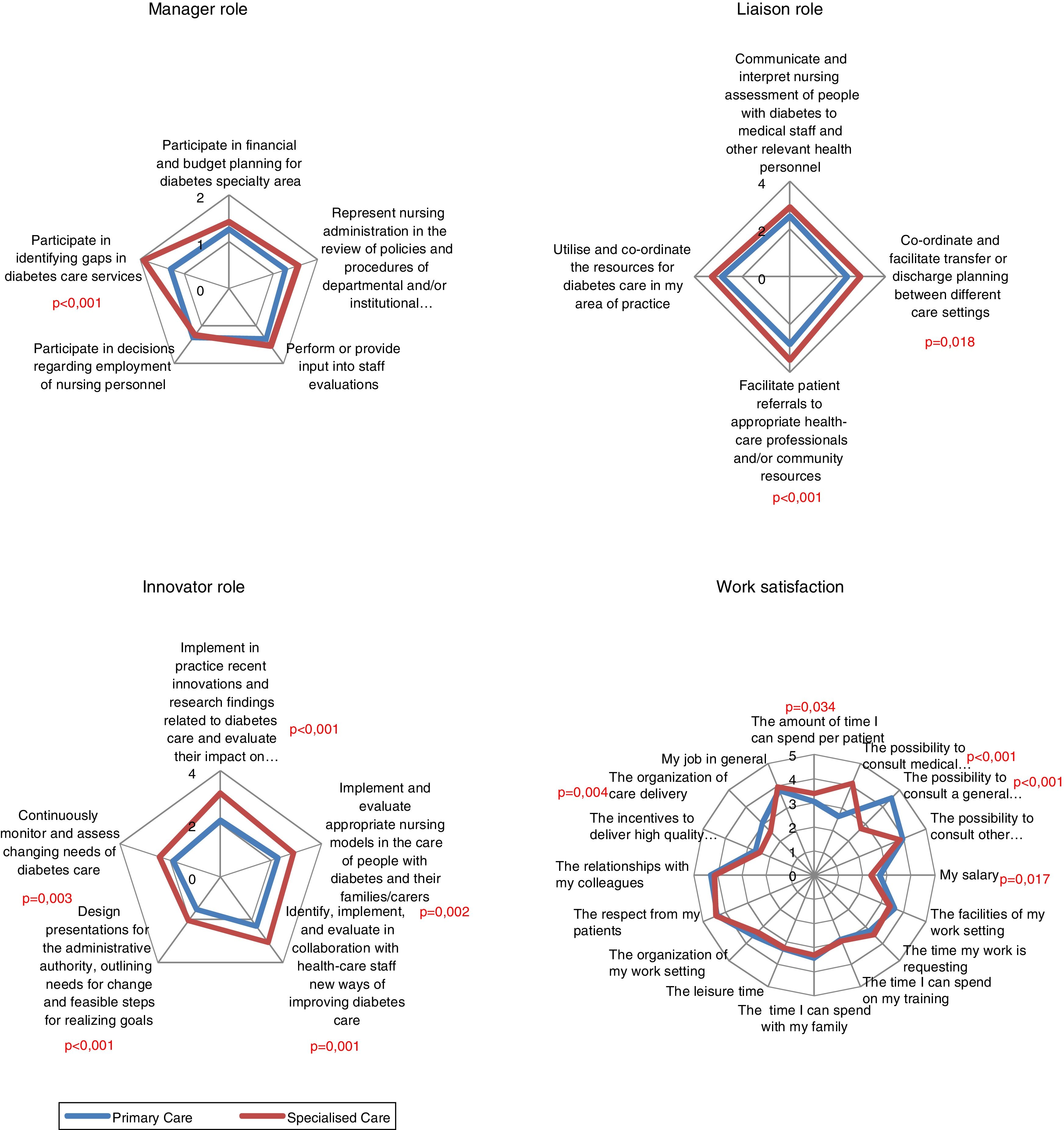

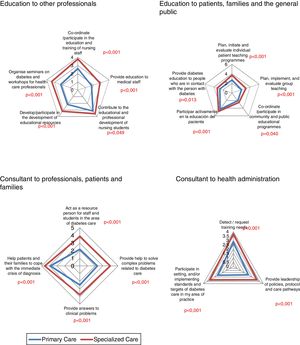

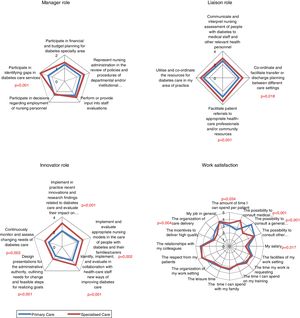

Degree of development of the professional roleOn evaluating each of the competences making up each role (expert clinical practice, educator, consultant, researcher, manager, liaison, innovator), SDC largely obtained the highest score in the competence integrating each role (Figs. 1–3). Of note was the low score observed in the competences of the role of researcher and manager in both the SDC and PC setting.

Degree of professional satisfaction with workIn general, the professionals of both settings were satisfied with their work, especially in the relationship with co-workers and patients, with no significant differences. Dissatisfaction was reported to be significantly greater in SDC in relation to the salary received (p=0.017) (Fig. 3).

DiscussionThis is the first in depth analysis of the training, competences and roles of DN in diabetes care in both SDC as well as PC. The results show that training of DN is very heterogeneous in both levels of care, although it is greater in DN in SDC. In general, DN in SDC more often assume roles corresponding to an APN. It is likely that the work setting in SDC may have led to the need for continuous or academic training with the aim of adapting to the changing needs of the patients. This aspect is especially relevant in several studies which have demonstrated that routine and accredited training of the professionals is associated with a greater probability of managing and educating more complex aspects of treatment16 and with better control of the diabetes of the patients attended.17 On the other hand, it was observed that the mean age of the education collective of SDC was close to the age of retirement (51.3 years), and this may lead to a problem related to professional replacement. These results have been corroborated in other studies in Europe, such as in Sweden where the mean age of DSN is 53.3 years, and in the United Kingdom it was estimated in 2011 that despite having accredited courses for educators in diabetes, 44% of the DSN would retire within 10 years, with few expectations of having professionals able to occupy their work positions.18,19

It was found that the competences related to the primary or secondary prevention, such as the detection of complications (foot examination, retinopathy screening) and cardiovascular risk factors (dyslipidemia, hypertension or smoking habit) are well implemented in PC. On the other hand, the present results indicate that the availability of structured programmes is low, group methods are little used, especially in PC, which actually has more space (classroom), and participation of the family in educational activities is low. This, together with the high rate of DN who provide education on demand in both settings demonstrates that there may be confusion between the content of structured education and information activities similar to what has been described in other studies.20 Taking into account that group education allows the use of more efficient and cost-effective methods for TED,21 it would be necessary to provide these professionals with specific training in methodologic techniques and the design of programmes in which the participation of the family is essential. The low application of programmes for education and care of diabetic foot, which is more focused on examination, especially in PC also agrees with the results of another study in Catalonia22 in which the lack of specific material for examination, the lack of professional training and the need to organise and coordinate care to diabetic feet in PC has shown to be the principal barriers to the application of these programmes. The creation of more multidisciplinary units of diabetic foot closely coordinated with the reference centres and the participation of DSN could facilitate the application of these specific programmes.

This study demonstrates the low implementation of programmes and downloading platforms of telemedicine devices specifically in PC. The capacities of older persons to use these means are often underestimated, but it is also true that the motivation or interest of professionals and organisational differences among centres may influence their use.23 On the other hand, the DN of SDC assume more competences related to the management of new sophisticated therapies according to the recommendations of clinical guidelines and consensus documents which advise that DSN with specific skills and experience should attend the educational needs of patients using these therapies.

The most notable presence of the role of educator aimed at both other professionals as well as patients and the roles of consultant and collaborator or liaison for both patients and the same organisation in SDC may justify recognition of the leadership of the professionals working in this setting.24 The good score obtained in SDC related to the role of consultant may support the capacity of introducing changes and improving practice within an interdisciplinary framework, since apart from responding to the needs of the patients or the relatives, this role may promote empowerment of both clinical nurses as well as the other professionals of the team, and it has recently been described as being a bridge between scientific knowledge and clinical practice.25

Although the role of investigator is more present in SDC, a low score was obtained in all the competences, and the limitation of the professionals to identify problems and make investigation questions was of note. This is likely due to the lack of scientific training of the professionals in the nursing degree. In this sense, we must trust the new generations of nurses with degrees, masters and doctorate theses, and their better training in the field of investigation. Improving the investigative capacity of nurses would contribute to filling the gap between investigation and clinical practice.26

Despite the manifest importance of coordination between the different healthcare levels,27 the professionals participating in this study reported deficient coordination and interrelation between the different healthcare levels. This problem remains unsolved and generalised in most countries and has shown to be a reason for the low degree of work satisfaction of the professionals involved.28

It is difficult to compare the grade of DN satisfaction with other studies because of the use of different measurement tools. However, similar to other studies, in the present study salary was one of the factors leading to low work satisfaction, and this may interfere with professional development.29 On comparison between the two healthcare settings, it was observed that SDC had the highest level of dissatisfaction with their salary. This may explain why the professionals with the greatest amount of university education have the lowest degree of satisfaction for not being compensated for their personal as well as economic effort. The lack of incentives to obtain postgraduate university education may minimise the development of competences related to quality healthcare practice or leadership of the most well prepared professionals.

Another aspect related to a high degree of satisfaction in the different dimensions evaluated was the availability of adequate space for educational activities (such as a classroom) since it is practically an essential resource for providing quality therapeutic education and for applying paedagogic techniques and strategies such as, among others, group education. We were unable to find studies which specifically evaluate this characteristic, but it has been reported that the physical structure where the work is performed has an impact on the grade of satisfaction.30

One of the main limitations was the lack of professional consensus in both healthcare settings, making sample calculation difficult. On the other hand, on being a descriptive study no causal factor for the results obtained can be established, thereby making the search for solutions difficult.

In addition, depending on the profile of the patient treated in each area, the educational needs may be different and the questionnaire does not provide a detailed description of the contents of an educational programme for each patient profile. This may explain the absence of significant differences in the services provided to the patients, especially those related to different aspects of treatment such as nutrition and exercise.

The lack of differences in the services provided to the patients, especially those related to different aspects of treatment such as nutrition and exercise can probably be explained by the type of questionnaire, which did not provide a depth description of how these services were carried out. For example, education related to exercise could be understood as the recommendation of walking every day to a person with T2D or how to adjust treatment in a person with T1D doing sports. It could also be explained by the presence of ambiguity in the professional roles in each setting. Likewise, the little difference between the evaluation of learning results and clinical results between the two healthcare levels could be an explanation.

It is of note that this is the first study to evaluate in depth the training, the competences and the development of the professional role of nurses attending people with diabetes in different healthcare settings, and thus, may represent the first step for the development of other investigations of the framework of nursing competences in TED in all of its areas.

In conclusion, the implementation of TED is disproportionate between the different healthcare settings in Catalonia. The DN in SDC have more university training in diabetes (master or postgraduate) and more continuing education in diabetes and therapeutic education and assume more roles of specialist clinical nurses. In addition, in SDC more work is made with structured TED programmes and strategies of group and individual education. The SDC also uses more telematic methods to control and follow patients. Evaluation of the interventions is more focused on the results of learning such as technical skills, problem solving and attitudes. On the contrary, DN in PC provide more services focused on changes in lifestyle and have better infrastructure for carrying out group work, although less than half use this methodology.

According to the results obtained and the scientific evidence currently available, the training of DN working in the care of people with diabetes should be accredited in order to increase the use of structured programmes and investigation by DNs in both healthcare settings.

ContributorsMV, had the original idea for the study, wrote the study protocol and mailed the questionnaires for the collected data and wrote the draft of the manuscript.

PIP and JMV were the doctoral thesis directors. They evaluated the methodology of the study protocol and were the guarantors. JMV performed the statistical analysis.

MJ participated in the study design, reviewed the study and collaborated in the final version of paper.

FundingThe present study did not receive any specific funding from private, commercial or non-profit agencies.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

The authors would like to thank to Anne-Marie Felton (DSN), President of Foundation of European Nurses in Diabetes (FEND) and to Bert Vrijhoef (PhD), Principal Investigator of the Study of European Nurses in Diabetes (SEND 2009), Department of Family Medicine, Maastricht University.

We also want to thank the diabetes nurses participating in this study, the Catalan Diabetes Association for its support (www.acdiabetis.org).

This study is part of the doctoral thesis so we also want to thank Pilar Isla (PhD) and Joaquin Moncho (PhD) as directors of this doctoral thesis.