Thyrotoxicosis is the clinical condition resulting from an excess of thyroid hormones for any reason. The main causes are Graves–Basedow disease, toxic multinodular goitre and toxic adenoma. The medical treatment to control thyroid function includes antithyroid drugs, beta blockers, iodine solutions, corticosteroids and cholestyramine. Although therapeutic plasma exchange is not generally part of the therapy, it is an alternative as a preliminary stage before the definitive treatment.

This procedure makes it possible to eliminate T4, T3, TSI, cytokines and amiodarone. In most cases, more than one cycle is necessary, either daily or every three days, until clinical improvement is observed. The effect on thyrotoxicosis is temporary, with an approximate duration of 24–48h.

This approach has been proposed as a safe and effective alternative when the medical treatment is contraindicated or not effective, and when there is multiple organ failure or emergency surgery is required.

La tirotoxicosis es el estado clínico resultado del exceso de hormonas tiroideas por cualquier causa. Las principales causas son la enfermedad de Graves-Basedow, el bocio multinodular tóxico y el adenoma tóxico. El tratamiento médico para controlar la función tiroidea incluye antitiroideos, betabloqueadores, preparaciones de yodo, corticoides y colestiramina. Aunque el recambio plasmático terapéutico no forma parte habitualmente de dicho tratamiento, resulta otra opción como paso previo a un tratamiento definitivo.

Dicho procedimiento permite eliminar T4, T3, TSI, citoquinas y amiodarona. Suele ser necesario más de un ciclo, diario o cada tres días hasta que se observe una mejoría clínica. El efecto sobre la tirotoxicosis es transitorio, con una duración aproximada de 24 a 48 horas.

Se ha planteado como alternativa terapéutica segura y eficaz cuando el tratamiento médico está contraindicado o es inefectivo, en presencia de fracaso multiorgánico o necesidad de cirugía de emergencia.

The patient is a 20-year-old woman with a history of Gilbert's syndrome. At age 14 she had her first episode of Graves–Basedow disease, which was adequately controlled with thiamazole for two years. At age 18 she had her first recurrence and received antithyroid drug therapy for a year. This treatment and follow-up were conducted in another medical department.

Eight months later, she was admitted again with weight loss of 2kg in two months and the following blood results: TSH 0.44mIU/l (0.48–4.17), free T4 1.44ng/dl (0.83–1.43), free T3 3.26pg/ml (3–4.7), TSI 2 (N<0.1). TPO and antithyroglobulin antibodies were positive. Neck ultrasound suggested thyroiditis, and no nodules were observed. As it was mild subclinical hyperthyroidism, a wait-and-see approach was adopted.

After two months of monitoring, the patient developed clear symptoms of hyperthyroidism with a significant increase in thyroid hormones: TSH<0.01mIU/l (0.55–4.78), free T4 9.09ng/dl (0.89–1.76), free T3>20pg/ml (2.3–4.2). Considering the clinical and analytical situation, treatment with thiamazole was reintroduced at a dose of 10mg/8h.

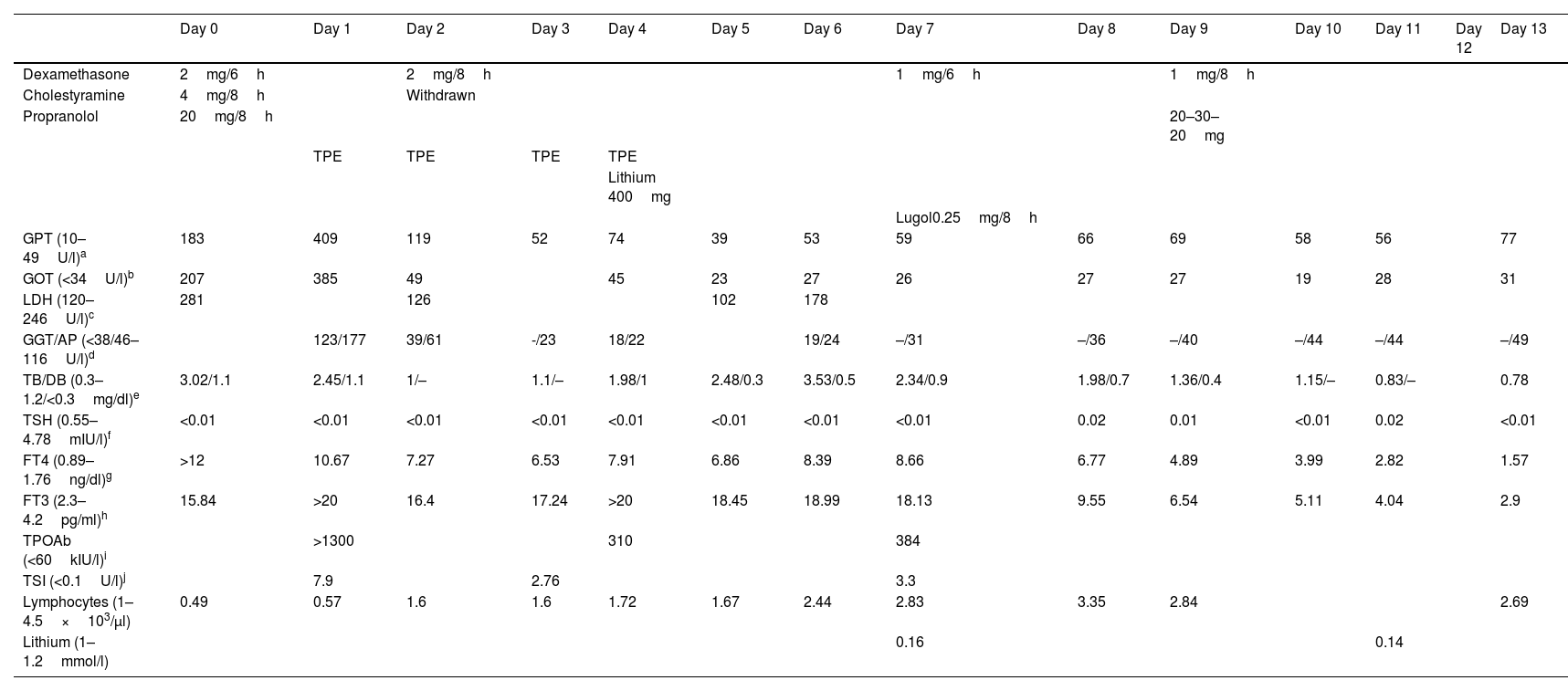

However, seven days later the treatment was interrupted due to a persistent elevation of thyroid hormones levels. Instead, propylthiouracil 200mg/6h and propranolol 20mg/8h were administered, with clinical improvement. After 10 days with this treatment, the patient went to Accident and Emergency with fever and general malaise, and blood tests showed a significant increase in transaminases and lymphopenia (Table 1). A concomitant infection was ruled out and the patient was admitted to hospital.

Pre-surgical analytical changes.

| Day 0 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Day 8 | Day 9 | Day 10 | Day 11 | Day 12 | Day 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone | 2mg/6h | 2mg/8h | 1mg/6h | 1mg/8h | ||||||||||

| Cholestyramine | 4mg/8h | Withdrawn | ||||||||||||

| Propranolol | 20mg/8h | 20–30–20mg | ||||||||||||

| TPE | TPE | TPE | TPE | |||||||||||

| Lithium 400mg | ||||||||||||||

| Lugol0.25mg/8h | ||||||||||||||

| GPT (10–49U/l)a | 183 | 409 | 119 | 52 | 74 | 39 | 53 | 59 | 66 | 69 | 58 | 56 | 77 | |

| GOT (<34U/l)b | 207 | 385 | 49 | 45 | 23 | 27 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 19 | 28 | 31 | ||

| LDH (120–246U/l)c | 281 | 126 | 102 | 178 | ||||||||||

| GGT/AP (<38/46–116U/l)d | 123/177 | 39/61 | -/23 | 18/22 | 19/24 | –/31 | –/36 | –/40 | –/44 | –/44 | –/49 | |||

| TB/DB (0.3–1.2/<0.3mg/dl)e | 3.02/1.1 | 2.45/1.1 | 1/– | 1.1/– | 1.98/1 | 2.48/0.3 | 3.53/0.5 | 2.34/0.9 | 1.98/0.7 | 1.36/0.4 | 1.15/– | 0.83/– | 0.78 | |

| TSH (0.55–4.78mIU/l)f | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.02 | <0.01 | |

| FT4 (0.89–1.76ng/dl)g | >12 | 10.67 | 7.27 | 6.53 | 7.91 | 6.86 | 8.39 | 8.66 | 6.77 | 4.89 | 3.99 | 2.82 | 1.57 | |

| FT3 (2.3–4.2pg/ml)h | 15.84 | >20 | 16.4 | 17.24 | >20 | 18.45 | 18.99 | 18.13 | 9.55 | 6.54 | 5.11 | 4.04 | 2.9 | |

| TPOAb (<60kIU/l)i | >1300 | 310 | 384 | |||||||||||

| TSI (<0.1U/l)j | 7.9 | 2.76 | 3.3 | |||||||||||

| Lymphocytes (1–4.5×103/μl) | 0.49 | 0.57 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.72 | 1.67 | 2.44 | 2.83 | 3.35 | 2.84 | 2.69 | |||

| Lithium (1–1.2mmol/l) | 0.16 | 0.14 |

The propylthiouracil was discontinued and the patient was started on dexamethasone 2mg/6h, propranolol 20mg/8h and cholestyramine 4mg/8h (this last drug was later withdrawn due to poor tolerance, including abdominal discomfort and nausea). The patient also received her first cycle of therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), with partial clinical improvement and a decrease in thyroid hormones by approximately 25% (Table 1).

Despite having completed four sessions of TPE with a total reduction of free T4 by 35.71%, a significant elevation of thyroid hormones (particularly free T3), palpitations and heat intolerance persisted, and lithium carbonate 400mg/24h and Lugol's iodine 0.25mg/8h were added. The patient's thyroid hormone levels returned to within normal range after one week and total thyroidectomy was performed the next day, without complications (Table 1).

As secondary effects of the TPE cycles, only itching without skin lesions was described, exclusively after first cycle.

ManagementThyrotoxicosis is described as the clinical condition resulting from an excess of thyroid hormones for any reason. Moreover, thyroid storm is an acute, life-threatening complication of hyperthyroidism which presents with multi-system involvement. The main causes of thyrotoxicosis are hyperthyroidism caused by Graves–Basedow disease, toxic multinodular goitre (MNG) and toxic adenoma.1 The medical treatment to control thyroid function includes antithyroid drugs, beta blockers, iodine solutions, corticosteroids and cholestyramine, before evaluating the possibility of definitive therapy with surgery or radioactive iodine.2

The use of TPE to control thyrotoxicosis was first described in 1970 by Ashkar et al.3 This procedure was applied in cases of toxic MNG, thyrotoxicosis secondary to Graves–Basedow disease and thyrotoxicosis induced by iodine or amiodarone. It was even used successfully in a case of thyrotoxicosis secondary to interferon alpha.4

TPE involves the extracorporeal filtration of blood to eliminate plasma and other substances (autoantibodies, immune complexes, cryoglobulins, endotoxins, lipoproteins and free and bound thyroid hormones) which play a role in pathologic immune responses.5 It may also eliminate amiodarone and its metabolites.6 Afterwards, plasma from a donor, fresh frozen plasma, albumin or a similar colloidal solution is administered.7 Although albumin binds thyroid hormone less avidly than thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG), it provides a much larger capacity for low-affinity binding, which may contribute to lower free thyroid hormone levels.8

Since its side effects include haemolysis, allergic reaction, infection, coagulation disorders, haemorrhage, hypocalcaemia, hypotension, vasovagal reactions, dyspnoea and seizure,8,9 it is contraindicated in cases of haemodynamic instability, active infection or increased risk of bleeding.10

Areas of uncertaintyAlthough dexamethasone and Lugol's solution particularly helped to reduce thyroid hormone levels, this was not enough to effectively control thyroid function (Table 1). TPE is not part of the general treatment for thyrotoxicosis, but it is an alternative when the medical treatment is contraindicated or ineffective, as a preliminary stage before the definitive treatment. In general terms, more than one cycle is required,1–3 either daily or every three days, until clinical improvement is observed.11 It is possible to achieve a decrease in thyroid hormones by over 50%.12 The effect on thyrotoxicosis is temporary, with an approximate duration of 24–48h.13 A multicentre retrospective study analysed the results of TPE on 22 patients with thyrotoxicosis (9 with Graves–Basedow disease and 13 with toxic nodules). An average of four cycles of TPE were administered (range: 2–9 cycles), and the levels of free T4 decreased by 41.7%. Clinical improvement was observed in most cases (91%).14

GuidelinesThe American Society for Apheresis recommends this procedure on patients with thyroid storm and severe symptoms if no improvement is observed after 24–48h of medical treatment or if there may be potentially severe effects due to the use of antithyroid drugs.15 Similar indications are included in the Japanese guidelines, which specify acute liver failure as a side effect.16

TPE has been suggested as a safe and effective alternative when the medical treatment is contraindicated or ineffective, as a previous step before total thyroidectomy, in cases of multiple organ failure or when emergency surgery is required.17,18

Conclusions and recommendationsIn line with the medical literature, TPE achieved a considerable reduction in free T4 in our patient, which led to better hormonal control prior to surgery.

Although the American Society for Apheresis recommends this procedure with a 2C grade of evidence,15 it should be considered an adequate therapeutic alternative.

Its effect is temporary, with a decrease in the levels of hormones and TSI. It improves the clinical symptoms and reduces the risk of thyrotoxicosis during surgery.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.