The quality of diabetes care varies from region to region. The objective of this study is to analyze the characteristics of care in different hospitals in Spain through a specific survey assessing different aspects of care for both children and adults.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional observational voluntary survey study, sent to the heads of the Endocrinology and Pediatric Endocrinology Departments or Units in public hospitals with more than 150 beds, during the first semester of 2021. A total of 105 responses were obtained, 55.5% of the 189 requested, which corresponded to a population served of 31,782,409 people, representing almost 80% of the total population served.

ResultsPatients with diabetes under 15 years of age are cared for by Pediatric Departments, but only 58% of them have a specific Diabetes Education Unit for children, and in 72% of the cases, there is one single nurse dedicated to these tasks, and not always full-time. Those over 15 years of age are attended by specialists in Endocrinology and Nutrition in 94.3 % of hospitals. There are Therapeutic Education Units in Diabetes in practically all hospitals (94.3%). However, Diabetes Day Hospitals exist in only 32 centres and cover 40.3% of the population, since in 22 provinces there are none. Virtual and telematic consultations, as well as retinography, are available in more than 70% of cases, but access to a Diabetic Foot Unit only in 54% of centres. Monographic technological consultations on diabetes have become widespread, but access to mental health specialists with diabetes training remains limited (24% of centres), and interdisciplinary (32%) or interlevel (12%) committees are very scarce.

ConclusionDiabetes care in Spain shows great variability from one region to another, and some deficiencies have been detected that affect a large part of the population, such as access to Diabetic Foot Units, as well as mental health specialists with specific training. The presence of multidisciplinary and mixed committees between levels of care remains scarce.

La calidad de la asistencia a la diabetes varía de unos lugares a otros. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar las características de la asistencia en los distintos centros hospitalarios de España mediante una encuesta específica valorando distintos aspectos de la asistencia tanto a niños como a adultos.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional transversal tipo encuesta voluntaria, enviada a los responsables de los Servicios o Unidades de Endocrinología y Endocrinología Pediátrica de los Centros Hospitalarios con asistencia pública de más de 150 camas, durante 2021. Se obtuvieron 105 respuestas, el 55,5 % de las 189 solicitadas, que correspondían a una población atendida de 31.782.409 personas, las cuales representan casi el 80% de la población atendida total.

ResultadosLos pacientes con diabetes menores de 15 años son atendidos por los Servicios de Pediatría, pero solo el 58% de ellos cuentan con Unidad de Educación en Diabetes específica para niños y en el 72% es un único profesional de enfermería el dedicado a estas labores y no siempre a tiempo completo.

Los mayores de 15 años son atendidos por especialistas en Endocrinología y Nutrición en prácticamente todos los casos. Existen Unidades de Educación terapéutica en Diabetes en prácticamente todos los hospitales (94,3%), Sin embargo, los Hospitales de Día de Diabetes existen en solo 32 centros y cubren el 40,3 % de la población atendida ya que en 22 provincias no existe ninguno. Las consultas virtuales y telemáticas, así como la retinografía están disponibles en más del 70 % de los casos, pero el acceso a una Unidad de Pie diabético solo en el 54 % de los centros.

Las consultas monográficas en tecnologías se han generalizado, pero sigue estando limitado el acceso a especialistas en Salud Mental con formación en diabetes (24 % de los centros) y las comisiones interdisciplinarias (32%) o interniveles (12%) son muy escasas.

ConclusiónLa atención a la diabetes es España muestra una gran variabilidad de unos territorios a otros y se han detectado algunas deficiencias que afectan a gran parte de la población como son el acceso a Unidades de Pie Diabético, así como a especialistas en Salud Mental con formación específica. La presencia de comisiones multidisciplinarias y mixtas entre los niveles asistenciales es aún escasa.

Diabetes care varies from one region to another depending on the available means and how the care is organised.1,2 Diabetes complications are known to be affected by the quality of such care.3,4 Here in Spain there is virtually universal public health care. However, care for a chronic disease such as diabetes varies according to the health service in each autonomous region or health area. In recent years, new care arrangements have also been introduced, such as diabetes day hospitals, diabetic foot units and dedicated clinics for different aspects of diabetes.

As there is a lack of data on this situation, the Grupo de Trabajo de Epidemiología de la Sociedad Española de Diabetes (GTE-SED) [Epidemiology Working Group of the Spanish Diabetes Society] decided to conduct a survey of Spanish hospitals to find out what is happening across Spain, in order to identify areas for improvement and raise awareness among health authorities.

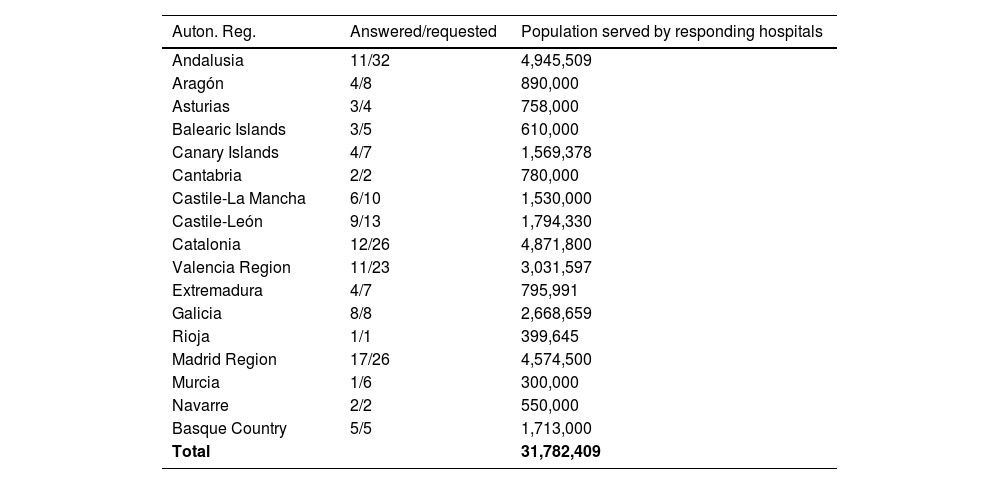

Material and methodsThe working group (GTE-SED) created a survey with 17 main items and in the first half of 2021 sent it to the healthcare professionals who manage the care of people with diabetes (specialists in endocrinology and nutrition, paediatrics or internal medicine) at all hospitals in Spain with more than 150 beds and with population allocation by the National Health System. There were a total of 189 hospitals, with the distribution shown in Table 1.

Hospitals surveyed by Autonomous Region.

| Auton. Reg. | Answered/requested | Population served by responding hospitals |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 11/32 | 4,945,509 |

| Aragón | 4/8 | 890,000 |

| Asturias | 3/4 | 758,000 |

| Balearic Islands | 3/5 | 610,000 |

| Canary Islands | 4/7 | 1,569,378 |

| Cantabria | 2/2 | 780,000 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 6/10 | 1,530,000 |

| Castile-León | 9/13 | 1,794,330 |

| Catalonia | 12/26 | 4,871,800 |

| Valencia Region | 11/23 | 3,031,597 |

| Extremadura | 4/7 | 795,991 |

| Galicia | 8/8 | 2,668,659 |

| Rioja | 1/1 | 399,645 |

| Madrid Region | 17/26 | 4,574,500 |

| Murcia | 1/6 | 300,000 |

| Navarre | 2/2 | 550,000 |

| Basque Country | 5/5 | 1,713,000 |

| Total | 31,782,409 |

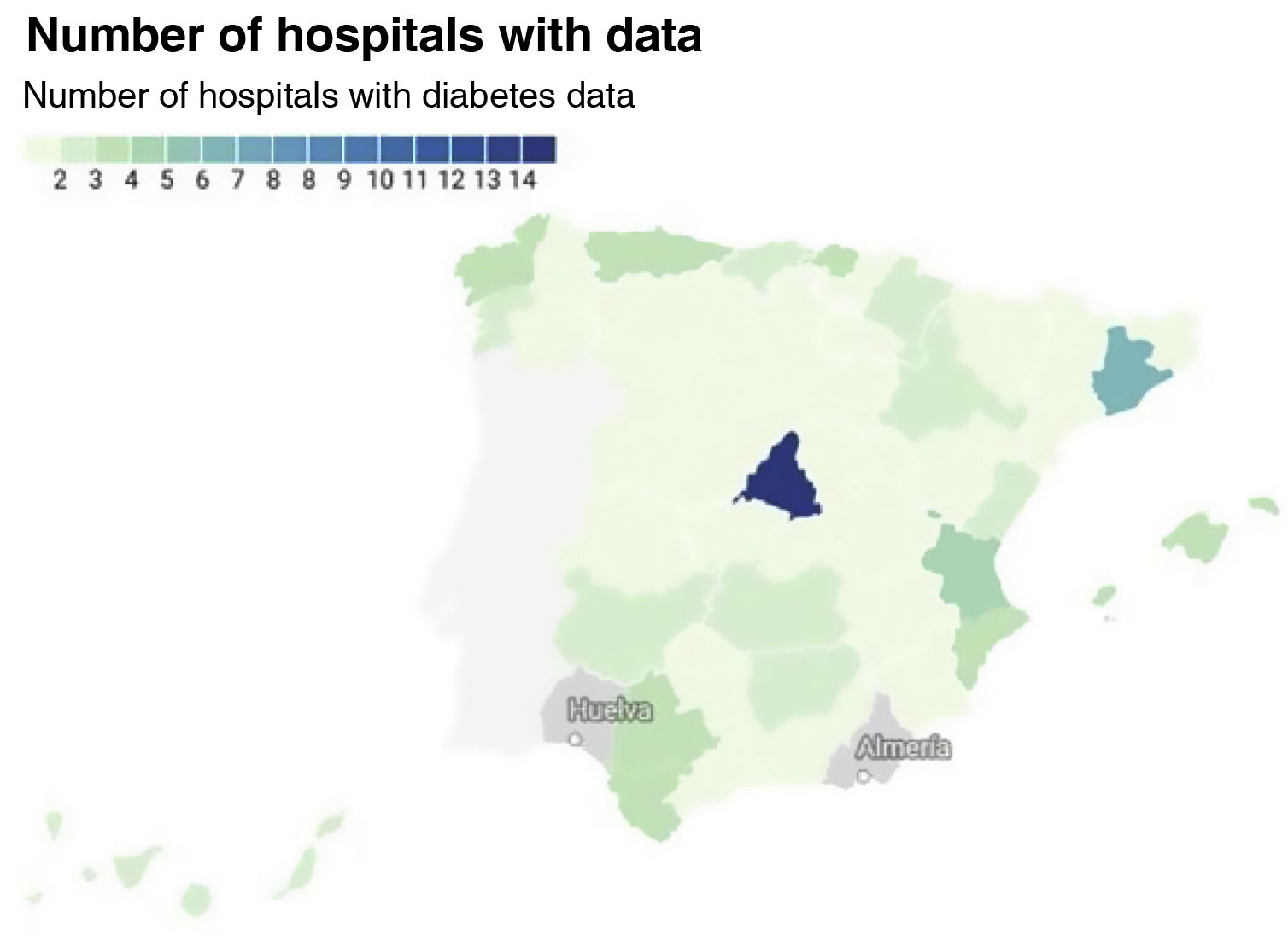

Out of a total of 189 hospitals, 105 responded. According to their own figures, all together they serve 31,782,409 people across Spain, representing about 80% of the entire population covered by the National Health System. Responses were obtained from all provinces except Huelva and Almería (Fig. 1).

Care for people with diabetes under 15 years of agePeople under the age of 15 with type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM) are looked after by paediatric services, except in three hospitals (one in Madrid Region, one in Valencia Region and one in Castile-León), where their care is provided by the endocrinology department.

Of the 87 hospitals where care for under 15s with DM is covered by paediatric services, 32 (37%) have only one paediatrician for these patients. At 29 of these centres (33%) there is no paediatrician dedicated full-time to diabetes care, the care provision only being part-time. In total, there are 165 paediatricians dedicated to the care of type 1 DM at these hospitals, 100 of whom (60.6%) work full-time.

Sixty-one hospitals, 58.1% of the total, have a diabetes education unit specifically for children. In many provinces, none of the hospitals have any such specific paediatric unit. At 43 hospitals (72%) there is only one qualified nurse dedicated to education in the paediatric education unit for type 1 DM and only 41 hospitals have full-time workers in such posts; in 20 hospitals the educators are part-time.

Care for people with diabetes aged 15 and overThe care of people with type 1 DM is provided by specialists in endocrinology and nutrition in 103 of the 105 hospitals; in one of these such care is provided by a referral endocrinologist from another centre and the other is a paediatric-only hospital.

The care of those with type 2 DM is provided by endocrinology and nutrition, except in three cases where it is provided by internal medicine.

The number of specialist physicians in endocrinology departments or units varies from one to 20, and in almost all cases the care of type 1 diabetes is provided by all physicians.

Almost all hospitals (94.3%) have diabetes therapeutic education units; more than 80% have at least two educators and cover almost the entire population served.

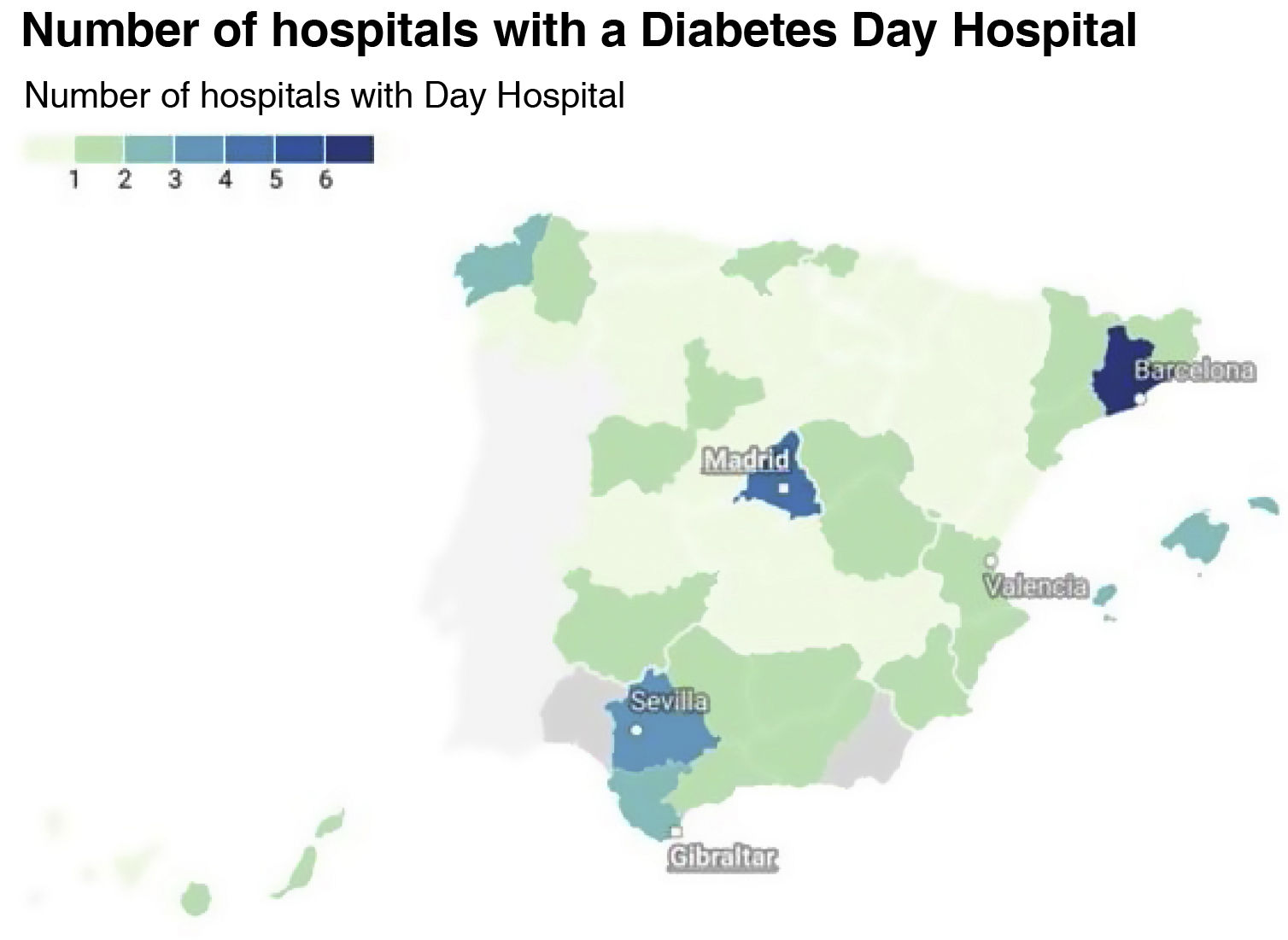

The distribution of diabetes day hospitals is very uneven in the different autonomous regions and provinces (Fig. 2). Some, such as Andalusia and Catalonia, have day hospitals in all provinces, at most hospitals. In other autonomous regions, such as Galicia or Castile-León, only some hospitals have them and 22 of the 48 provinces for which we have data lack this resource. Consequently, out of the hospitals that responded to this survey, those with a day hospital cover less than half (40.3%) of the total population served.

Day hospitals operate in all cases from Monday to Friday, starting between 8 and 9 a.m.; in most cases they operate for seven hours (until 3 p.m.) and in others until 5 p.m., 7 p.m. or 10 p.m.

Care pathways between primary and specialised care incorporating care circuits and support are in place at most hospitals (63.8%). However, only 38 hospitals (36.2%) have an alternative pathway to the emergency department for people with diabetes in acute or difficult-to-manage situations.

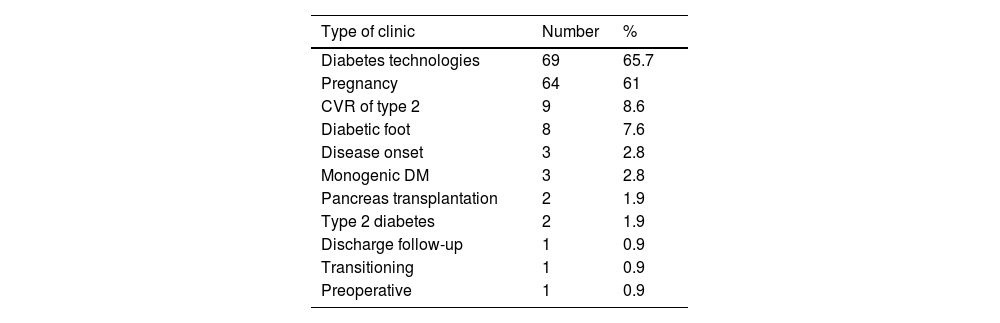

More than three quarters, 81 out of 105 (77.1%), of hospitals caring for people with type 1 DM have a dedicated diabetes clinic. Table 2 shows the frequency of each type of dedicated clinic; the most widespread are the diabetes technology clinics, which include continuous insulin infusion systems, and the diabetes and pregnancy clinic.

Dedicated diabetes clinics.

| Type of clinic | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes technologies | 69 | 65.7 |

| Pregnancy | 64 | 61 |

| CVR of type 2 | 9 | 8.6 |

| Diabetic foot | 8 | 7.6 |

| Disease onset | 3 | 2.8 |

| Monogenic DM | 3 | 2.8 |

| Pancreas transplantation | 2 | 1.9 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2 | 1.9 |

| Discharge follow-up | 1 | 0.9 |

| Transitioning | 1 | 0.9 |

| Preoperative | 1 | 0.9 |

Non-mydriatic retinography is available for patients with diabetes at 81 (77.7%) of the hospitals. In 60 of them it is carried out at some facility in the health area and in just over half of them (42), at the hospital itself. Only four provinces do not have access to non-mydriatic retinography.

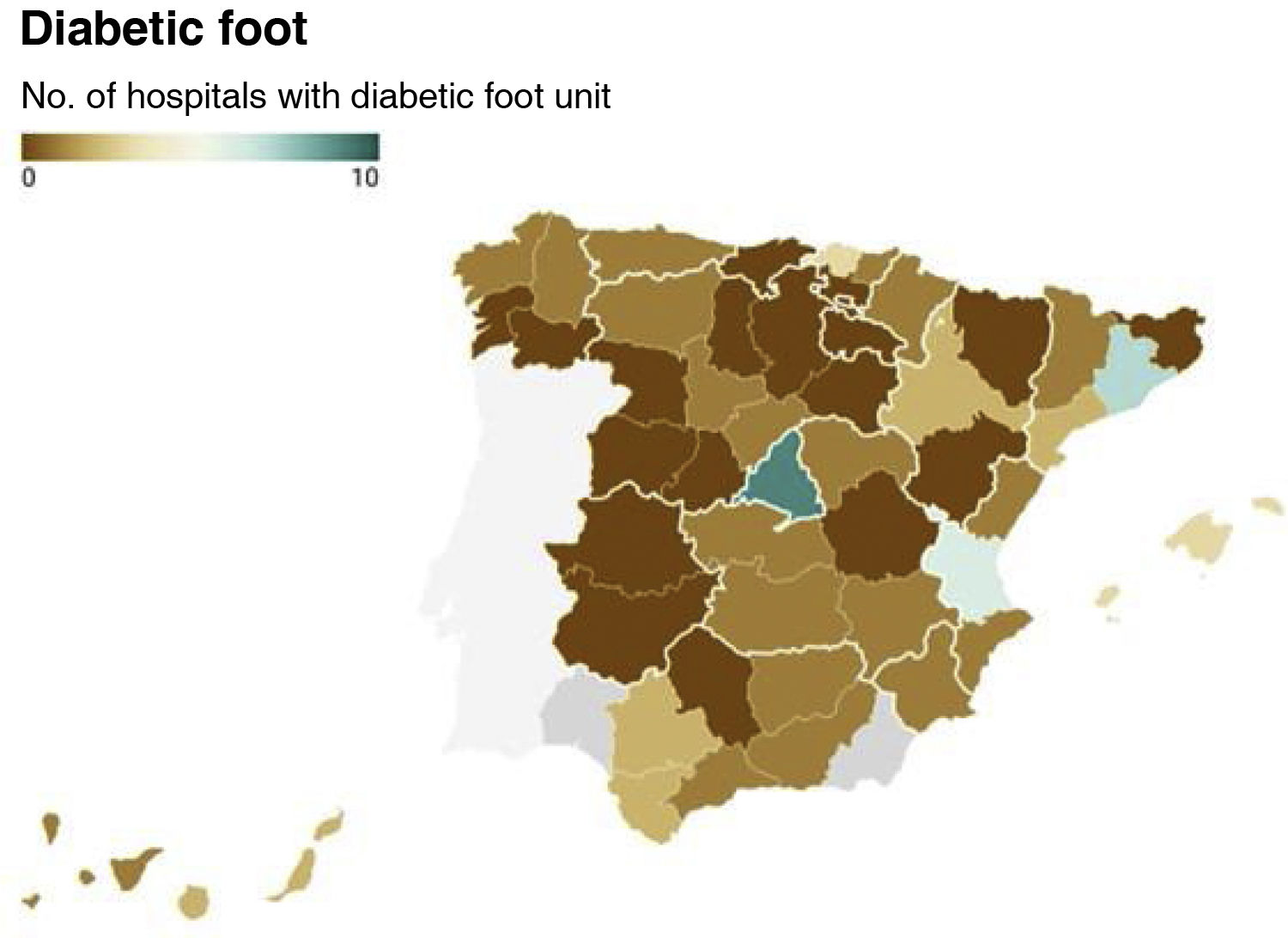

There is access to a diabetic foot unit at 54% of the hospitals (57), either on the premises (45) or at another centre (12) in the health area, but there are still 18 provinces without access to a specialised diabetic foot unit (Fig. 3).

Telematic virtual consultation with health centres takes place at 70% of hospitals. A slightly higher percentage (74%) have virtual consultations with patients.

In 34 hospitals (32.4%) there are multidisciplinary care committees specifically for dealing with diabetes. Joint committees with primary care, however, are only set up at 13 (12%) of all the responding hospitals and in only 10 provinces.

Some 38.1% of hospitals have a dietetics and nutrition technician with specific knowledge for patients with diabetes. Most (60%) have only one of these specialists, with 40% having more than one.

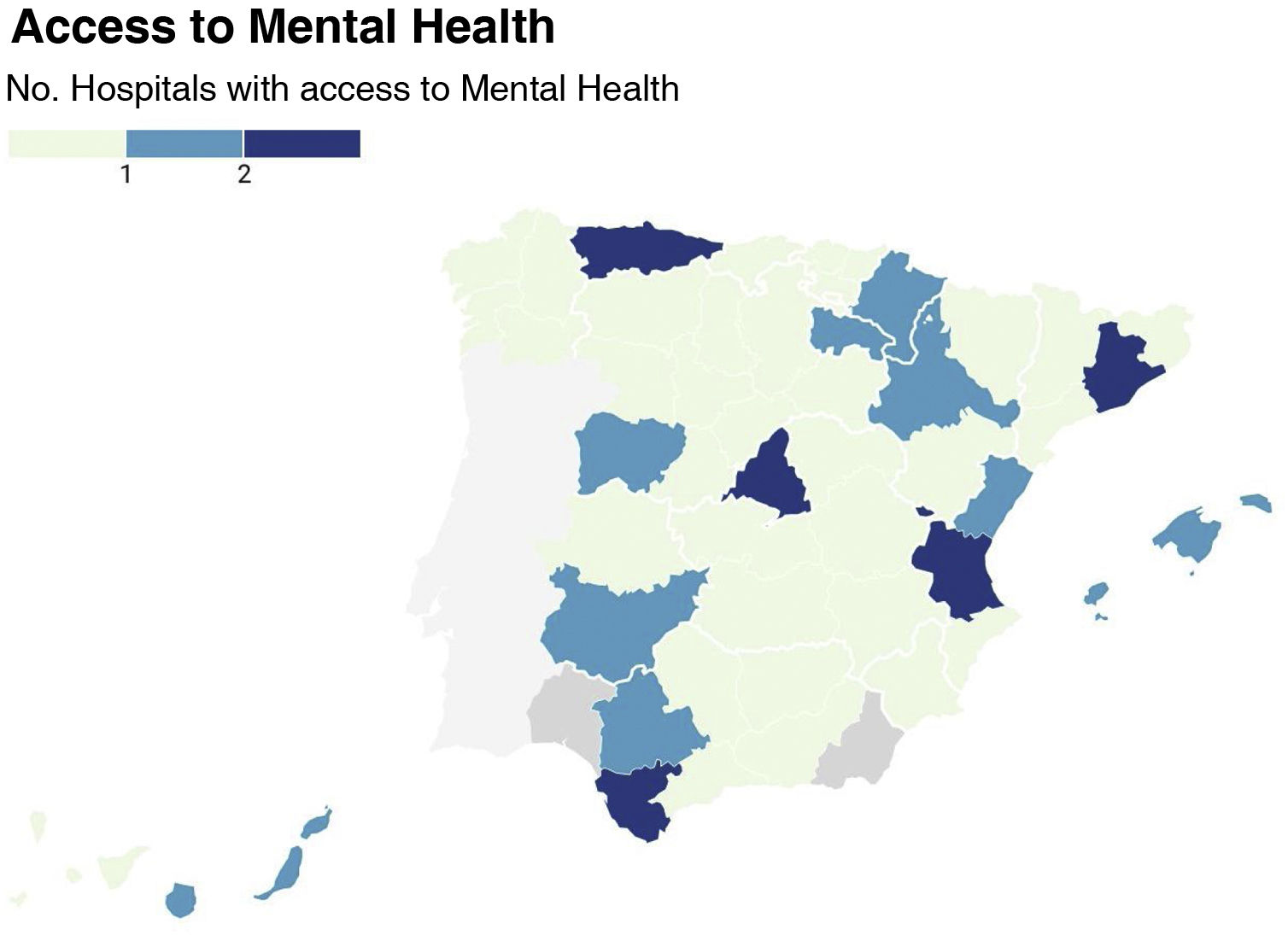

Referral to a mental health specialist familiar with the management of patients with diabetes is only possible in 25 hospitals, so 77% of the population does not have this service (Fig. 4).

DiscussionThe results of this survey confirm significant variability in diabetes care across Spain.

Children under the age of 15 with diabetes are cared for by paediatric specialists, but at many hospitals even that dedicated diabetes specialist is not full-time, despite diabetes being the most challenging chronic disease, and particularly at a time when technological advances in diabetes management and treatment require much fuller commitment. Dedicated education units also fail to reach the entire paediatric population, despite the fact that their special characteristics make such provision recommendable.5

Day hospitals are a reality in a significant part of the country, but more than half of the population is still without such cover. Some autonomous regions, such as Andalusia, have promoted the implementation of this service at all major hospitals and in all provinces, but in other regions, only a part of the population is covered. In some areas there is no day hospital provision at all, which probably means a deficit of care for people with diabetes compared to the rest of the country. Separate emergency care facilities for people with diabetes are even rarer and exist in only one third of the centres.

Accessibility to a multidisciplinary diabetic foot unit is considered essential for reducing the number of amputations in people with diabetes.6 However, as we found in this survey, such access is not yet guaranteed for a significant part of the population with diabetes here in Spain. New diabetic foot units still need to be set up where they are lacking.

In line with our findings, the lack of human resources for the care of people with type 1 diabetes is reported in parts of neighbouring countries such as France7, and the deficiencies are even greater in Eastern European countries.8 In 2013, 34 out of 64 general hospitals in Spain had diabetic foot units, and it would seem that the situation has only slightly improved.9 We were unable to find information in the literature on the distribution of the different specialised resources to compare the situation in our country with other similar countries.

Non-mydriatic retinography has been proven effective for over 10 years10 and is the way to ensure adequate eye screening for all people with diabetes. We therefore found it striking that, although widespread, it has not yet been implemented in all health areas.

Aided by the COVID-19 pandemic11, we have seen the spread of virtual consultations, both between healthcare professionals and with patients, and these are now taking place in over 70% of centres.

It is worth noting, however, that there are few multidisciplinary committees for diabetes care and that only in a small percentage of cases are there stable links in the form of committees with primary care. Although there are protocols for action, stable institutionalised links are very necessary in a disease as prevalent and significant as diabetes, given that shared care between primary care and hospitals helps ensure consistent disease control.12

Last of all, we detected another important problem, which is the difficulty in referring our patients with diabetes to mental health specialists who are familiar with the disease, especially when depression and other disorders are closely associated with the control of diabetes and future outcomes for these patients.13,14

In conclusion, diabetes care in Spain varies greatly from one part of the country to another and we detected deficiencies which affect a large part of the population. These include access to diabetic foot units and to mental health specialists with specific training. Additionally, very few areas seem to have multidisciplinary and mixed committees linking different levels of care.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.