Patients with untreated chronic adrenal insufficiency, high-dose glucocorticoid treatment, and Cushing's syndrome are known to frequently experience psychiatric changes. However, psychiatric changes, occurring after glucocorticoid replacement therapy that has been started following the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency, are less well known.

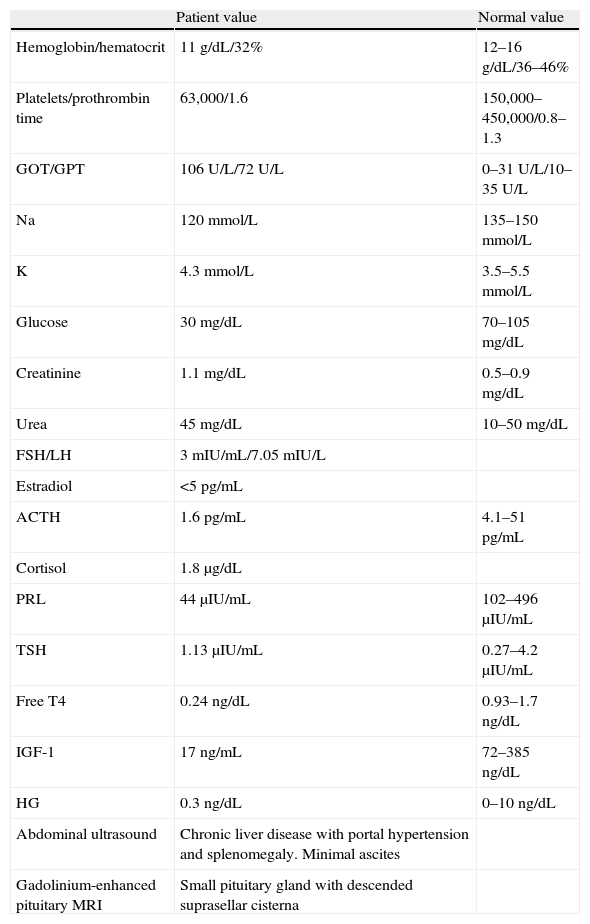

We report the case of a 53-year-old female patient with a personal history of a complicated delivery in 1981 (28 years ago) requiring several transfusions of packed red cells for severe bleeding and hypotension. After delivery, the patient experienced agalactia, early menopause (amenorrhea since delivery) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. She was on follow-up at the gastrointestinal clinic, but had not returned there for 8 years, and had been diagnosed with liver disease with Child C stage cirrhosis induced by HCV. The patient was admitted to hospital on December 2009 for obnubilation, bradypsychia, impaired speech, and temporal and spatial disorientation secondary to hyponatremia and hypoglycemia. She also reported significant fatigue, a depressive mood, and weight loss over several years. Examination revealed eyebrow alopecia, absence of pubic and axillary hair, pallor, and thinness. Table 1 shows laboratory and imaging data.

Laboratory and imaging data.

| Patient value | Normal value | |

| Hemoglobin/hematocrit | 11g/dL/32% | 12–16g/dL/36–46% |

| Platelets/prothrombin time | 63,000/1.6 | 150,000–450,000/0.8–1.3 |

| GOT/GPT | 106U/L/72U/L | 0–31U/L/10–35U/L |

| Na | 120mmol/L | 135–150mmol/L |

| K | 4.3mmol/L | 3.5–5.5mmol/L |

| Glucose | 30mg/dL | 70–105mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 1.1mg/dL | 0.5–0.9mg/dL |

| Urea | 45mg/dL | 10–50mg/dL |

| FSH/LH | 3mIU/mL/7.05mIU/L | |

| Estradiol | <5pg/mL | |

| ACTH | 1.6pg/mL | 4.1–51pg/mL |

| Cortisol | 1.8μg/dL | |

| PRL | 44μIU/mL | 102–496μIU/mL |

| TSH | 1.13μIU/mL | 0.27–4.2μIU/mL |

| Free T4 | 0.24ng/dL | 0.93–1.7ng/dL |

| IGF-1 | 17ng/mL | 72–385ng/dL |

| HG | 0.3ng/dL | 0–10ng/dL |

| Abdominal ultrasound | Chronic liver disease with portal hypertension and splenomegaly. Minimal ascites | |

| Gadolinium-enhanced pituitary MRI | Small pituitary gland with descended suprasellar cisterna |

Based on these clinical and laboratory findings, the patient was diagnosed with hypopituitarism due to Sheehan's syndrome. Replacement therapy was started with levothyroxine (25μg/day) and hydrocortisone (60mg/day in three divided doses). Her clinical condition improved after the start of treatment, with normalization of blood glucose levels and correction of hyponatremia, but three days later the patient experienced anxiety, euphoria, and lack of inhibition. This condition progressed in two days to a hallucinatory psychosis with visual hallucinations with no delusional interpretation and partial subsequent recall. As there was no personal or family history of psychiatric disease or use of toxic substances, and after ruling out an infectious etiology to account for the condition, a “steroid psychotic crisis” was diagnosed, and treatment was started with tiapride and haloperidol. Glucocorticoid doses were decreased to 10mg/day.

The patient experienced a gradual improvement in the five days following the start of treatment. The psychotic symptoms disappeared, and treatment with psychodrugs was discontinued at two weeks and has not been needed since then. After 6 days of treatment with hydrocortisone 10mg/day, the dose was increased to 30mg/day. The patient then experienced a mild exacerbation of the psychotic conditions which required a dose reduction to 10mg/day again. This dose was subsequently increased very slowly and gradually.

The patient is currently being treated with hydrocortisone 20mg/day and levothyroxine 75μg/day.

Sheehan's syndrome, currently uncommon thanks to improved obstetric procedures, is caused by pituitary infarction after severe bleeding during or after delivery. Clinical signs vary, depending on the severity of the condition and range from acute severe panhypopituitarism to less severe forms including agalactia, lack of resumption of the menstrual cycle after delivery, and a clinical picture of indolent hypopituitarism.1 In such cases, prolactin, gonadotropin, and growth hormone deficiency occur in 90–100% of patients, while ACTH and TSH deficiency is a little less common (60–75% of patients). Diabetes insipidus rarely occurs. The most common water and electrolyte change in Sheehan's syndrome is hyponatremia (occurring in 35–65% of patients), resulting from cortisol deficiency, hypothyroidism, and a potentially impaired vasopressin secretion.2 These patients often experience psychiatric changes such as depression, impaired memory, and difficulty in concentration, caused by untreated, long-standing hypothyroidism and chronic adrenal insufficiency. These changes are resolved when replacement therapy is started.

As regards psychiatric pathology and glucocorticoids, psychiatric changes are common in patients with untreated, long-standing hypocortisolism, as previously discussed. Psychiatric changes caused by the administration of high glucocorticoid doses, which usually occur early after the start of treatment,3 and those occurring in patients with Cushing's syndrome are also common and well known.4 The condition of our patient is less common and less well known because the psychiatric changes occurred when glucocorticoid replacement therapy was started after the diagnosis of secondary adrenal insufficiency.5 The pathogenesis of this complication is unclear. One explanatory theory is that the chronic state of hypocortisolism induces an adaptive mechanism by which the overexpression and hypersensitization of cerebral glucocorticoid receptors occur at the central level6 to compensate for a cortisol deficiency. Such upregulation results in a supraphysiological response to replacement therapy with physiological glucocorticoid doses started after the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. If treatment is started in such cases at a higher dosage, than necessary, as occurred in our patient (hydrocortisone 60mg/day), the risk of that complication is greater. The maintenance of treatment with low glucocorticoid doses leads to a reduced receptor activity and number, which would explain why the supraphysiological response is self-limiting and why the psychiatric clinical signs are reversed.7

Thus, in patients diagnosed with Sheehan's syndrome with long-standing hypopituitarism, and in general in patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency who show psychiatric changes at the start of glucocorticoid therapy, treatment should be reduced or discontinued. Treatment should then be restarted at very low, slowly increasing doses.

Please cite this article as: Martín López M, et al. Psicosis alucinatoria aguda secundaria a tratamiento con glucocorticoides orales en una paciente diagnosticada de síndrome de Sheehan. Endocrinol Nutr. 2011;58:445–6.