Ganglioneuroma (Gn) is a benign tumor of the sympathetic nervous system that may occur along the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia, from the neck to the pelvis, and occasionally in the adrenal medulla. Adrenal Gn (AGn) usually occurs asymptomatically in patients under 20 years of age and is incidentally diagnosed in imaging tests requested for other reasons. Despite its benign nature, conversion to a malignant schwannoma has been documented in some cases, and it has been associated with tumors such as pheochromocytoma. Gn is treated by surgical resection and has an excellent prognosis. We report two patients with AGn diagnosed and operated on at our hospital.

Case 1. This was an 18-year-old female outpatient with an unremarkable history who attended for non-specific abdominal pain and was found to have a solid left adrenal mass in an ultrasound examination. A computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the presence of a homogeneous, solid adrenal tumor 6cm in diameter showing peripheral enhancement. Laboratory tests and functional hormone screening tests were normal. Based on the diagnosis of a nonfunctioning adrenal mass, laparoscopic left adrenalectomy was performed. The patient was discharged 24h after surgery, and a 7cm tumor pathologically diagnosed as Gn was found in the surgical specimen.

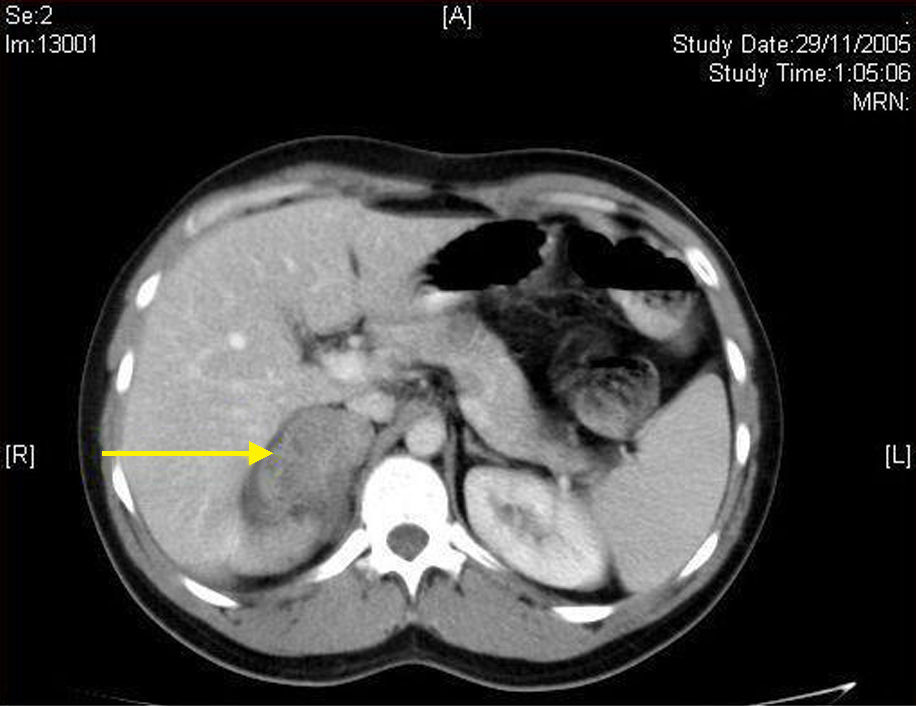

Case 2. This was a 28-year-old male patient with no remarkable history except for recurrent episodes of gastroenteritis and non-specific abdominal pain. An outpatient ultrasonography revealed a suspected right adrenal tumor. An abdominal CT scan confirmed the presence of a 5.8cm×4cm adrenal mass with a mixed low density. As with the previous patient, routine laboratory tests and blood hormone profile were normal. A non-functioning incidental adrenal tumor was diagnosed, and laparoscopic right adrenalectomy was performed. The patient was also discharged at 24h with no postoperative complications, and the pathological department reported a ganglioneuroma.

Gn is a rare, slowly growing tumor arising from primary sympathetic neurons of the neural crest. Gn belongs to the group of neurogenic tumors arising at this level, together with ganglioblastoma and neuroblastoma, but unlike these it consists of mature ganglion cells with no malignant potential.1–5 There is controversy as to whether Gn may occur de novo (primary Gn) or is the result of differentiation and maturation from ganglioblastoma or neuroblastoma.3,4 Tumors occur along the paravertebral sympathetic chain, from the neck to the pelvis, and occasionally in the adrenal medulla. They are most commonly located in the posterior mediastinum (40%) and retroperitoneum (37%), and more rarely in the anterior mediastinum, stomach, appendix, or prostate.1–5 Adrenal Gn accounts for approximately 15–30% of cases.

The incidence of AGn has increased in recent years as the result of the growing detection rate of incidentalomas in increasingly performed imaging tests of an improved quality. It is estimated that an adrenal tumor is incidentally found in 1–10% of abdominal CT scans. Of these, 1–6% are Gns.1 Although cases have also been reported in children, AGn mainly affects young adults with no sex predominance.1,2 Approximately half the patients have no symptoms, and when these occur, the most common clinical signs include non-specific abdominal pain or a palpable mass. Gns are usually non-secretory from the functional viewpoint, but 20–30% secrete catecholamines and metabolites. When hormone activity exists, diarrhea (release of vasoactive intestinal peptide), sweating, or high blood pressure may be associated, but these do not cause clinical emergencies, unlike in pheochromocytoma.4

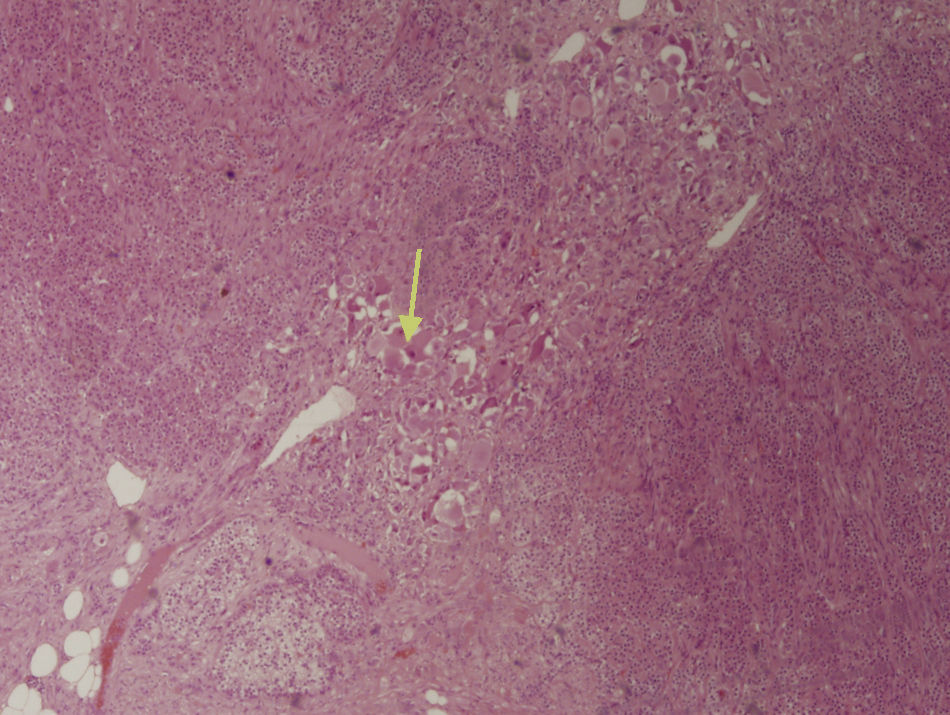

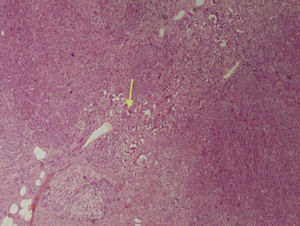

The first step in diagnosis always consists of hormone tests to show a non-functioning tumor: free cortisol in 24-h urine, suppression with dexamethasone 1mg, serum basal cortisol, ACTH, renin, plasma aldosterone, and catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) and their metabolites in blood and urine.3 The most helpful imaging tests are abdominal CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which have been shown to be superior to ultrasonography for the detection and characterization of adrenal disease.1 Gn is seen at CT as a well-defined, oval or lobulated solid mass with a low attenuation (usually less than 40 Hounsfield units) and a fibrous capsule (Fig. 1). Intratumoral calcifications are seen in 42–60% of cases, and may sometimes be heterogeneous after contrast administration.2,3,5,6 In MRI they show a low intensity signal in T1 and heterogeneity with high intensity in T2.5 Positron Emission Tomography (PET) has recently been incorporated to complement both tests in Gn diagnosis and, above all, to rule out malignant adrenal neoplastic conditions.1 Final diagnosis is made after histopathological analysis of the surgical specimen. The characteristic microscopic appearance is a uniform image with a stroma consisting of irregularly intertwined transversely and longitudinally oriented Schwann cells. Fat may occasionally be found. Relatively mature neurons with little Nissl substance and forming small groups or nests are found scattered throughout this Schwannian background. A bulky eosinophilic cytoplasm and one to three nuclei with mild to moderate atypia are typically seen (Fig. 2). The use of fine needle aspiration is limited by the possibility that the lesion is malignant (adrenal carcinoma or metastasis) or cystic in nature and by the difficulty in differentiating adenoma from carcinoma.2,3

The indication of surgery for incidental, non-functioning adrenal tumors is not clearly defined and will depend on lesion size and radiographic characteristics. However, surgery should be performed on symptomatic tumors greater than 6cm in diameter (an increased incidence of carcinoma has been seen in these lesions) or showing radiographic characteristics of malignancy.3,7 Clinical and radiographic monitoring is usually done for lesions less than 4cm in size, although some authors advise surgical excision in young patients because of the very long follow-up that would be required and the anxiety this may cause.7,8 Treatment for lesions ranging from 4 and 6cm in size is controversial, and both surgical excision and monitoring have been recommended. Surgery should be considered if the tumor grows or radiographic signs of malignancy occur.3,7

Laparoscopy has become the procedure of choice for all adrenal pathology, including incidental, on-functioning masses, and is increasingly less limited by size.8 There is no current agreement about the maximum tumor size amenable to laparoscopic surgery. The traditionally accepted limit is 6cm, but there are many series reporting surgery for greater tumors, up to 13cm in size.1,7–10 A transperitoneal approach is usually used, but a retroperitoneal approach is preferred by some groups. Today, the presence of an invasive malignant tumor or venous thrombosis associated with the renal or suprarenal veins is an absolute contraindication.7–10 The prognosis of AGn after surgical resection is excellent, even when complete excision is not possible.10 Tumor recurrence is rare, and should be considered to result from an incomplete initial surgery (and should therefore be called “persistence” instead).

Please cite this article as: Titos García A, et al. Ganglioneuroma como causa infrecuente de tumor suprarrenal. Endocrinol Nutr. 2011;58(8):443–6.