As a result of the immunodeficiency associated with their condition, people living with HIV (PLHIV), are usually considered a risk group in epidemics caused by infectious agents, whether this is the annual influenza viruses or others which have emerged intermittently over the last few decades.

In the case of this new epidemic, the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2), there is no evidence to support that PLHIV have a different clinical course, except perhaps, for those with CD4 levels CD4 <200cells/μl; this point however, although logical in theory, has not been fully confirmed.1 However, a significant percentage of PLHIV, a third in the largest cohort in our Autonomous Region, are over the age of 50,2 and so are at higher risk of having chronic diseases such as high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease and chronic lung disease, and a higher percentage smoke, meaning a greater risk of respiratory infections,3,4 and a greater risk of dying in the event of suffering from COVID-19.5,6

One of the characteristics of COVID-19 is its high transmission and mortality rates in long-term care facilities (LTCF) and residential care homes for older people in the Western countries most affected by the pandemic.7,8 We would like to report on cases of PLHIV who have had COVID-19 treated in our hospital. Most were infected due to an outbreak in a LTCF for PLHIV with mainly neurological disabilities who require care which they cannot receive in their community environment. Nine of the ten residents were infected; the resident not infected was in another facility recovering from status epilepticus at the time of the outbreak.

There have not been many reported cases of COVID-19 in PLHIV. Those we have reviewed from here in Spain and Italy9–11 include a total of 103 cases in centres that cover several thousand patients (only 68 confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and the rest clinically suspected), which would strongly suggest that PLHIV are not a special risk group for contracting COVID-19.

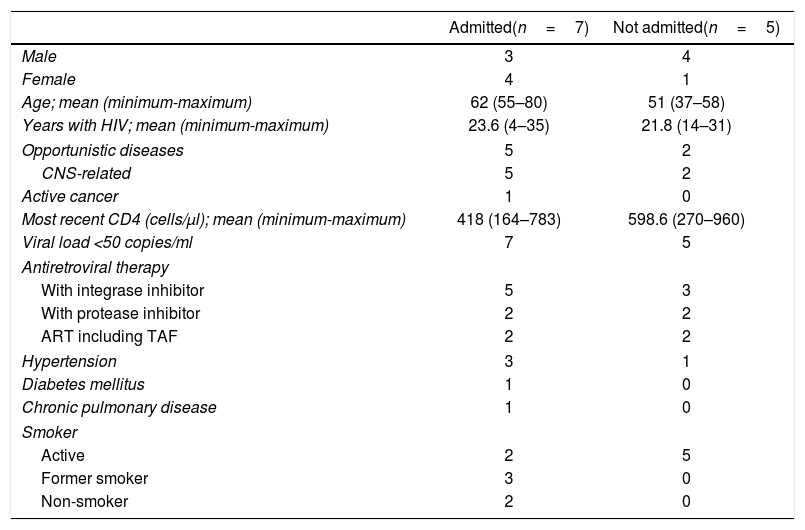

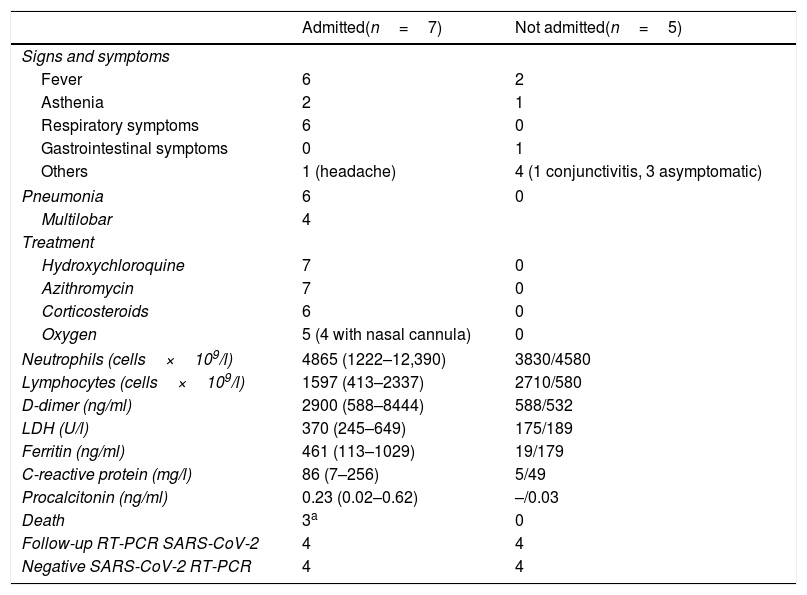

As of 15 May 2020, we had diagnosed 317 cases of RT-PCR-confirmed COVID-19 in our service area, 12 of them PLHIV. Seven patients (five from the LTCF) required hospital admission and the remaining five (four from the LTCF) had telephone follow-up without being admitted (Tables 1 and 2). All 12 were on antiretroviral treatment (ART), all had viral load <50copies/ml, and ten had CD4 lymphocyte counts >200cells/μl. The ART was not modified in any of the cases, so none received lopinavir/ritonavir. All the patients gave their consent for the publication of clinical data.

Baseline characteristics of the patients.

| Admitted(n=7) | Not admitted(n=5) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 3 | 4 |

| Female | 4 | 1 |

| Age; mean (minimum-maximum) | 62 (55–80) | 51 (37–58) |

| Years with HIV; mean (minimum-maximum) | 23.6 (4–35) | 21.8 (14–31) |

| Opportunistic diseases | 5 | 2 |

| CNS-related | 5 | 2 |

| Active cancer | 1 | 0 |

| Most recent CD4 (cells/μl); mean (minimum-maximum) | 418 (164–783) | 598.6 (270–960) |

| Viral load <50 copies/ml | 7 | 5 |

| Antiretroviral therapy | ||

| With integrase inhibitor | 5 | 3 |

| With protease inhibitor | 2 | 2 |

| ART including TAF | 2 | 2 |

| Hypertension | 3 | 1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 | 0 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1 | 0 |

| Smoker | ||

| Active | 2 | 5 |

| Former smoker | 3 | 0 |

| Non-smoker | 2 | 0 |

CNS: central nervous system; TAF: tenofovir alafenamide; ART: antiretroviral treatment.

Signs and symptoms, treatment, analytical parameters at admission and outcomes for PLHIV with COVID-19.

| Admitted(n=7) | Not admitted(n=5) | |

|---|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | ||

| Fever | 6 | 2 |

| Asthenia | 2 | 1 |

| Respiratory symptoms | 6 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 0 | 1 |

| Others | 1 (headache) | 4 (1 conjunctivitis, 3 asymptomatic) |

| Pneumonia | 6 | 0 |

| Multilobar | 4 | |

| Treatment | ||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 7 | 0 |

| Azithromycin | 7 | 0 |

| Corticosteroids | 6 | 0 |

| Oxygen | 5 (4 with nasal cannula) | 0 |

| Neutrophils (cells×109/l) | 4865 (1222–12,390) | 3830/4580 |

| Lymphocytes (cells×109/l) | 1597 (413–2337) | 2710/580 |

| D-dimer (ng/ml) | 2900 (588–8444) | 588/532 |

| LDH (U/l) | 370 (245–649) | 175/189 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 461 (113–1029) | 19/179 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 86 (7–256) | 5/49 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/ml) | 0.23 (0.02–0.62) | –/0.03 |

| Death | 3a | 0 |

| Follow-up RT-PCR SARS-CoV-2 | 4 | 4 |

| Negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR | 4 | 4 |

The laboratory values for the admitted patients are expressed as mean (minimum value-maximum value). Only two of the patients not admitted had blood tests in A&E; the values expressed correspond to each of them.

Of the nine patients from LTCF, seven had suffered at least one opportunistic infection (OI), in six cases related to the central nervous system (CNS) and in another with no clear history of OI, but with a psychiatric condition related to intravenous drug addiction, which made it difficult to specify subjective symptoms such as asthenia, dysgeusia or anosmia. Lastly, was the oldest resident, aged 80, without criteria for AIDS, but with a history of alcoholism and chronic liver disease. Of the five who were admitted, all had fever and four also had respiratory symptoms with infiltrates on the chest X-ray.

The other three PLHIV diagnosed came from their own homes. One was a male patient over 70 years of age with HIV-associated dementia and bilateral pneumonia. Another was a woman who consulted for persistent left retro-orbital headache, in whom we found occupation of the ethmoid sinus and meatus of the left nostril, and diagnosed her with a relapse of her breast cancer; she had completed chemotherapy five months earlier, and had local recurrence on the surgical scar, multiple lymphadenopathy and lung, liver and adrenal metastases, but she did not have pneumonia or any respiratory symptoms. The third case, also a woman, consulted for asthenia, itchy throat and conjunctivitis; she was monitored at home, only having low-grade fever ≤37.5°C.

All of the hospitalised patients were treated with the combination of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and azithromycin. Six patients, including the five who had pneumonia, also received corticosteroids at different doses, due to the practically daily changes in the treatment recommendations, which we all experienced in the early weeks of the epidemic. Four patients with positive pneumococcal urinary antigen test in urine also received the appropriate antibiotic therapy. They were all also given a prophylaxis dose of low molecular weight heparin.

The patients who were not admitted were only prescribed symptomatic treatment if necessary, and antibiotics in the case of one patient with positive pneumococcal urinary antigen test without respiratory symptoms, but with a suspect infiltrate on X-ray (perhaps a chest computed tomography scan might have detected some infiltrates, due to its greater sensitivity), and blood test showing increased CRP.

Three of the 12 patients died, two in connection with COVID-19. One was the 80-year-old patient who had numerous comorbidities, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease with glomerular filtration rate measured according to CKD/EPI of 13–18ml/min/1.73m2 and chronic liver disease without decompensation; her respiratory symptoms began to worsen 48 hours after admission with progressive dyspnoea, need for increased levels of oxygen therapy and non-productive cough; she was started on corticosteroids and blood tests showed an increase in ferritin, CRP, procalcitonin (2.64ng/ml) and especially D-dimer (55,000ng/ml) and neutrophils (16,290/mm3). This patient made very poor progress and it was decided to limit therapeutic effort. She died while receiving end of life care on her fourth day in hospital.

The second person who died was a 56-year-old patient with hypertension and a history of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, HIV-associated cognitive impairment and minimally functioning left lung, due to elevated hemidiaphragm as a consequence of a stab wound, which had required splenectomy in his adolescence. The patient had increased dyspnoea which he was tolerating well; it was difficult to administer oxygen as he was unable to cooperate with the treatment. Radiological progression of the infiltrate was identified in the right side of his chest plus contralateral involvement. Blood tests showed a moderate increase in ferritin and CRP and a decrease in D-dimer to 50% of the value on admission. He died of cardiorespiratory arrest on his fifth day in hospital.

Both the above patients had positive pneumococcal urinary antigen tests and were on antibiotic treatment.

The third death was a result of cancer recurrence. The patient had been discharged, but was readmitted because of poor headache control and left exophthalmos; the ENT assessment concluded that infiltration of the cancer in her left paranasal sinuses was displacing her eyeball and was possibly the cause of her headache. On readmission she had negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR and antibody determination by immunochromatography was also negative.

Now the peak of the epidemic in our area has passed, we can say that if we leave out the nine cases involving patients who were residents in the LTCF, the incidence of COVID-19 in our PLHIV cohort was very low, with only three out of almost 300 patients we monitor at our clinic. This puts us at just over 1%, although obviously we cannot rule out asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic episodes which did not require a medical consultation.

The immunological status of our patients, ten with CD4 >200 cells/μl, and the fact that all had undetectable viral load, is very similar to that of PLHIV in the series we reviewed,9–11 in which only ten cases had CD4 <200cells/μl, and five detectable viral load; one case with both criteria was a concomitant late diagnosis of HIV and COVID-19.9 Ten critical cases were described, with three deaths,10,11 and another was still in the ICU with assisted ventilation at the time of publication.9

The fact that all the residents living in the LTCF at that time developed COVID-19 shows us the ease of spread of the virus in closed communities, where the introduction of the virus by a worker from outside the institution resulted in transmission to all the residents and some caregivers, with the sad toll of two deaths. Due to the short period of time in which the onset of symptoms occurred in all those affected, 28 March to 4 April, we believe that when the first case was diagnosed on 2 April, they were all infected, but at different pre-symptomatic stages and possibly with mild symptoms. As the epidemic has evolved, we have learned the importance of transmission in the incubation period, before the appearance of the first most characteristic symptoms, such as fever, cough and dyspnoea.12 Nevertheless, due to the cognitive status of the residents, all except one having neuropsychiatric impairment, we understand that it was very difficult to maintain prevention and isolation measures, despite the efforts of the caregivers.

We have follow-up SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR results for eight of the patients. One was found to be negative four weeks after the onset of symptoms, when readmitted with her active cancer. In the seven LTCF patients who overcame COVID-19, five were negative at follow-up five weeks after the start of the outbreak, and in the two who had COVID-19 but were asymptomatic or had very mild symptoms and so were not admitted, it was seven and nine weeks respectively before they had a negative RT-PCR result.

In terms of treatment, in all of the patients we used the drugs we had available and which might be effective against SARS-CoV-213: HCQ, azithromycin, corticosteroids, but not tocilizumab, as none of the patients were on either invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation, this being a necessary requirement for its use in our hospital at that time due to the limited availability of the drug. We also did not prescribe lopinavir/ritonavir, in order not to modify any antiretroviral treatment. We do not know for sure if use of lopinavir/ritonavir has modified the course of COVID-19 and this issue has remained unresolved in observational studies which included many more patients.14,15 We can confirm that the patients who were not admitted all had an uncomplicated disease course until the condition resolved, without receiving any of these active substances.

Our series provides data on the high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 in closed communities and the difficulties in preventing its spread in this environment, due to the virus's ability to be transmitted in the asymptomatic phase of the disease. The limitations of the series are related to the small sample size and the fact that we cannot make comparisons between admitted and non-admitted patients or between residents in the LTCF and residents in the community. We also do not believe that it is applicable to other groups in view of the special characteristics of neurocognitive involvement in most of our patients.

Please cite this article as: Cucurull-Canosa J, Vega-Molpeceres S, Damián-Rodríguez JA, Pons-Viñas E. Descripción de 12 pacientes VIH positivos que han padecido la COVID-19 en nuestra área. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:208–210.