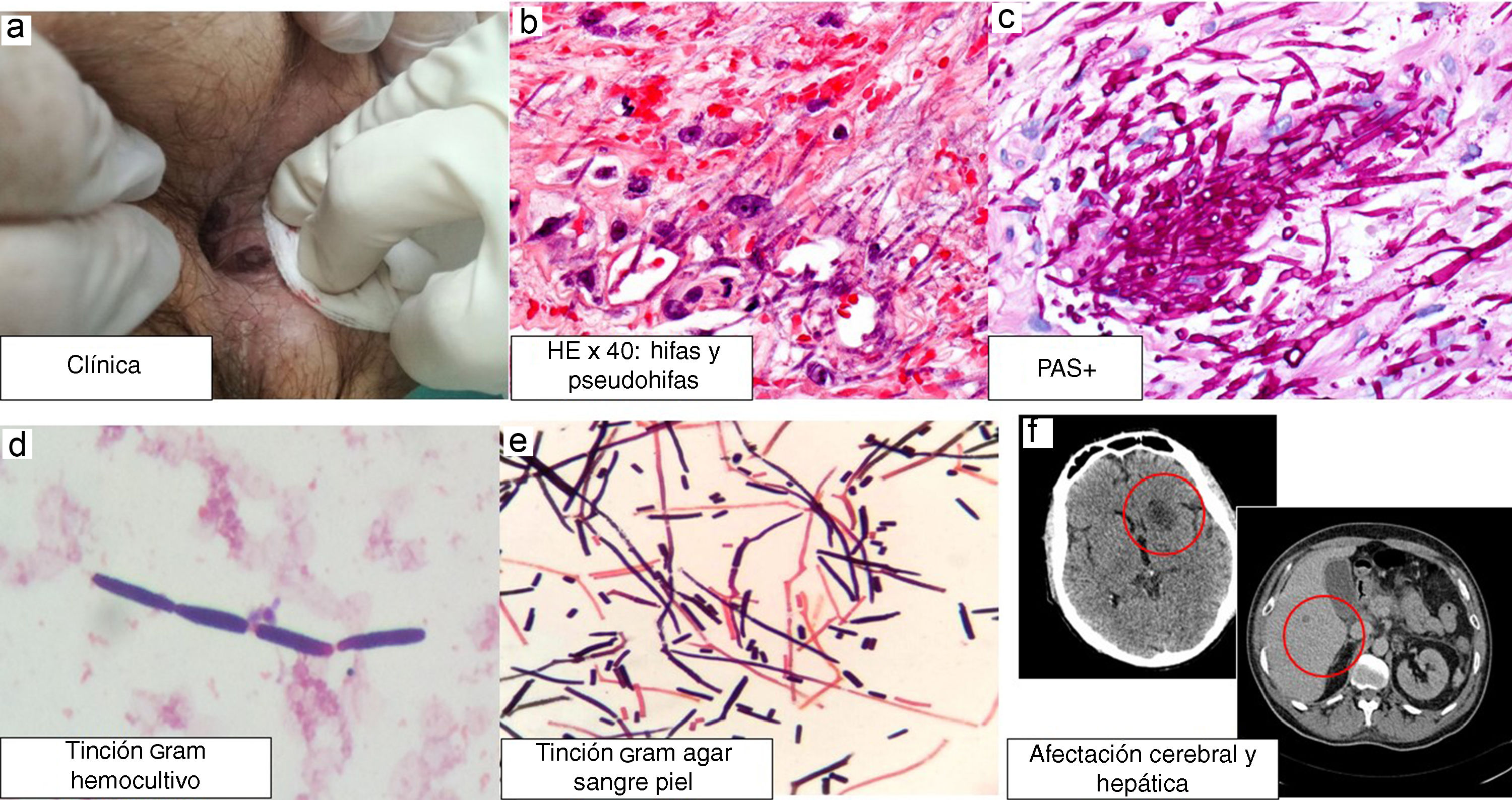

This was a 47-year-old male patient diagnosed in 2012 with stage IVA mantle cell lymphoma with lymph node, spleen, bone marrow, ileum and gastrointestinal tract involvement, in complete response after treatment with R-CHOP and R-DHAP, rituximab and ibrutinib. He had been admitted to the Haematology Department for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation from a haploidentical related donor, with subsequent pancytopenia. On day 11 post-transplant the patient developed abdominal pain, ascites and pleural effusion. He was referred for Dermatology assessment of asymptomatic hyperpigmented lesions in his anal mucosa. Examination revealed blackish-brown necrotic plaques extending from his anal mucosa to the outside (Fig. 1). Pathology examination showed (Fig. 1) squamous mucosa extensively ulcerated and presence of numerous pseudohyphae within the vessels and in the adjacent tissue, positive with the PAS (periodic acid-Schiff) and Grocott stain histochemical techniques. The pathology diagnosis was cutaneous angioinvasive mycosis. The biopsy was cultured and after 48h of incubation, growth of whitish and flat colonies was observed, identified as Saprochaete clavata.

S. clavata was also isolated in the two blood cultures extracted on the same day as the biopsy, with a time to positivity of 23.4h. In both samples, the identification was made using MALDI-TOF® (Bruker), with a score of 1.546. The isolated colonies were sent to a reference centre (Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Carlos III Health Institute]), which confirmed the identification. The antifungal susceptibility testing was performed by broth microdilution using the Sensititre® system (Thermo Scientific) and following the EUCAST criteria. Although there are no defined susceptibility criteria for these fungi, S. clavata is intrinsically resistant to echinocandins (anidulafungin, micafungin and caspofungin). The minimum inhibitory concentrations for the rest of the systemic antifungals were: amphotericin B (0.25μg/ml), 5-fluorocytosine (0.12μg/ml), fluconazole (32μg/ml), voriconazole (0.5μg/ml) and posaconazole (0.25μg/ml) (Fig. 1).

In the staging CT, lesions were found in the brain, liver and lungs, in addition to the gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 1).

Treatment was prescribed with liposomal amphotericin B 5mg/kg and 5-fluorocytosine 37.5mg/kg/6h, and the patient was transferred to the ICU in view of his poor progress with persistence of the fever and cerebral lesions, which ultimately led to his death two months after admission.

Invasive fungal infections are more common in immunosuppressed patients, particularly those with haematological malignancies, agranulocytosis and allogeneic transplantation. Infections of this type have increased in recent years and have become one of the leading causes of death in these patients. The most common agents include the genera Candida, Aspergillus and Mucor.1

Fungi of the genus Geotrichum are ubiquitous, filamentous, similar to a yeast, and are frequently isolated in soil, air, water, milk, clothing and vegetables, as well as in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and other mammals. The genus Geotrichum is composed of 18 species; the most common in human pathology are Geotrichum clavatum (reclassified as S. clavata) and Geotrichum capitatum (reclassified as Saprochaete capitata).2 The most common source for acquiring the infection is the ingestion of food, in particular cheese, as these fungi are used in the maturation process.3

Infections by these fungi are very rare. In fact, until a few years ago they were not considered pathogenic. However, corresponding with the increase in immunosuppressed patients in our clinics, we have begun to see opportunistic infections caused by these microorganisms.3

In the multicentre international FungiScope Registry4 they report 23 cases of infections by Saprochaete species over a period of 12 years. Of the 23 cases, 14 were caused by S. capitata, five by S. clavata and two by G. candidum. The infected patients were severely immunocompromised, with fungaemia and organ involvement, and the outcome was fatal in 65% of the cases, despite the antifungal treatment. In these cases, fungaemia was the most common form of presentation, in addition to solid organ involvement (lung, liver, spleen, central nervous system). The poor prognosis of this infection (65% mortality rate compared to 35% in candidaemia) means that we need to find better ways of treating these conditions.4

Following a search of the literature, we found only one case which showed images of skin manifestations, described as disseminated pink papular lesions.5 We found no images like those of our patient in the form of necrotic plaques in the mucous membrane. It is worth noting that our patient's skin lesions were only discovered thanks to a rigorous and exhaustive examination by the treating physician.

In terms of diagnosis, as this is a very ubiquitous fungus with little pathogenic power, repeated isolation in samples or, thought to be more specific, isolation in biopsies, either a punch biopsy or fine needle aspiration, is required.2,4

As far as treatment is concerned, there are no standardised regimens. These fungi are known to be resistant to echinocandins (anidulafungin, caspofungin and micafungin) and have different degrees of susceptibility to voriconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, flucytosine and amphotericin B. In the registry with the most patients,4 they consider the combination amphotericin B and 5-fluorocytosine to be active against Saprochaete spp. and Geotrichum spp.6

Please cite this article as: Salgüero Fernández I, Nájera Botello L, Orden Martinez B, Roustan Gullón G. Fungemia diseminada por Saprochaete clavata. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019;37:283–284.