Carbapenems resistance is a growing phenomenon and a threat to public health because of the reduced therapeutic options for resistant infections.

MethodsA retrospective case–control study was conducted in 2 tertiary-care hospitals in Medellín, Colombia. Fifty patients infected with ertapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae were compared with a control group consisting of 100 patients with infections caused by ertapenem susceptible enterobacteriaceae. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to identify factors that best explain ertapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae infections.

ResultsThe factors associated with ertapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae infections were prior exposure to carbapenems (adjusted OR 3.43; 95% IC 1.08–10.87) and prior exposure to cefepime (adjusted OR 6.46; 95% IC 1.08–38.38).

ConclusionPrior exposure to antibiotics is the factor that best explains the ertapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae infection in this population, highlighting the importance of antimicrobial stewardship programs in hospitals.

La resistencia a carbapenémicos es un fenómeno creciente y una amenaza para la salud pública, pues reduce las posibilidades terapéuticas en microorganismos resistentes.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo de casos y controles en 2 instituciones hospitalarias de Medellín, Colombia. Cincuenta pacientes con infecciones por enterobacterias resistentes a ertapenem fueron comparados con 100 pacientes con infecciones por enterobacterias sensibles a ertapenem. Un modelo multivariado de regresión logística se empleó para identificar los factores que mejor explican la infección por enterobacterias resistentes a ertapenem.

ResultadosLa exposición previa a carbapenémicos (OR ajustada 3,43; IC 95% 1,08-10,87) y la exposición previa a cefepima (OR ajustada 6,46; IC 95% 1,08-38,38) fueron los factores asociados a la infección por enterobacterias resistentes a ertapenem en la población estudiada.

ConclusiónLa exposición previa a antibióticos es el factor que mejor explica la infección por enterobacterias resistentes a ertapenem en esta población, poniendo de relieve la importancia de programas de optimización del uso de antimicrobianos en instituciones hospitalarias.

Enterobacteriaceae are among the most common micro-organisms in hospital institutions in Colombia, but, in addition to their high prevalence, in the past decade an emergence of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae,1–3 antibiotics used to treat serious infections and, in particular, for micro-organisms that express resistance mechanisms to other antimicrobials, limiting their clinical use, has been observed.

The increase of resistance to carbapenems has been documented by research groups and surveillance networks, such as the GERMEN Group, which, in a recent study in 22 hospitals in Medellín, Colombia, found a significant increase in carbapenem resistance between 2007 and 2012.4 However, the knowledge of local epidemiology, as well as the factors that could be related to infection by these micro-organisms in the hospital population is still precarious. Therefore, this study was conducted with the objective of determining factors related to the ertapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (ERE) infection in hospitalised patients in 2 tertiary care health institutions in Medellín, Colombia.

MethodsA retrospective, non-matched case–control study was conducted at 2 hospital institutions in Medellín. The cases were 50 adult patients with ERE infections, while the control group consisted of patients hospitalised with infections caused by ertapenem-susceptible enterobacteriaceae. For each case, 2 control patients were selected, considering the same proportion of patients for each enterobacteriaceae species and each sample collection site. Patients who were admitted with a diagnosis of infection by the same enterobacteriaceae or those for which the isolate was obtained in the 2 days after admission were excluded, as were patients for whom the isolate corresponded to a colonisation.

The information was taken from the medical record and the laboratory databases. For each patient, we screened demographic information, medical history, comorbidities and underlying illnesses, and antibiotics administered for ≥48h with anti-gram-negative activity, invasive procedures performed during the hospitalisation and prior to the isolation, as well as variables related to the bacterial isolation.

The antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed using the MicroScan Walk-Away® system (Dade Behring Inc., West Sacramento, CA, USA) and Vitek® 2 Compact (bioMérieux, Durham, NC, USA). Ertapenem resistance was defined using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) 2013 interpretation criteria (susceptible ≤0.5μg/ml and resistant ≥2μg/ml),5 with the exception of 13 isolates from 2010, that were interpreted with the cut-off values from the same year (susceptible ≤2μg/ml and resistant ≥8μg/ml).6 Intermediate susceptibility results were considered resistant. The modified Hodge test was performed with the 10μg5 ertapenem disks.

The information was analysed with the SPSS® program (IBM SPSS Statistics 21). The continuous variables were recoded to categorical variables, considering the median value. The categorical variables were compared with Fisher's exact test or the Chi2 test. The odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. A multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed and the adjusted OR and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. A p≤0.05 value was considered significant.

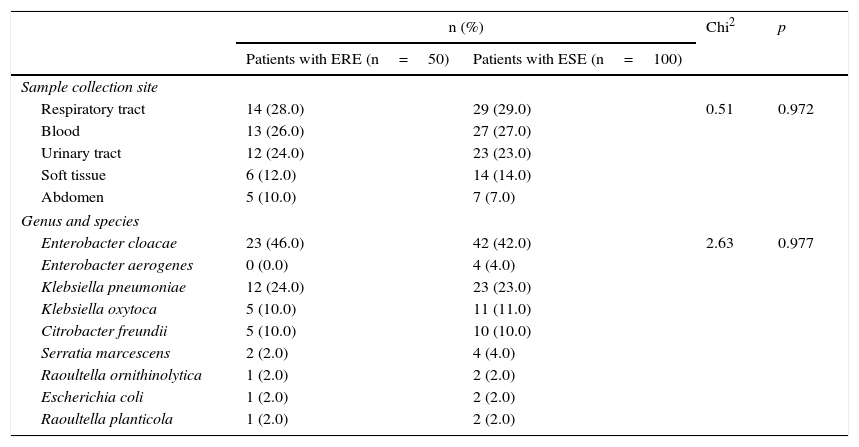

Results50 patients with ERE isolates were analysed. The most common species was Enterobacter cloacae (46.0%), followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (24.0%), Klebsiella oxytoca and Citrobacter freundii (10.0% each). The most common sample collection sites were the respiratory tract (28.0%), the bloodstream (24.0%) and the urinary tract (24.0%) (Table 1). In the control group, due to the difficulty of finding the entire number of subjects with ertapenem-susceptible Enterobacter cloacae infections, 4 isolates of Enterobacter aerogenes were included.

Distribution of the sample collection sites and the bacterial species isolated from patients with ertapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae and ertapenem-susceptible enterobacteriaceae infections.

| n (%) | Chi2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with ERE (n=50) | Patients with ESE (n=100) | |||

| Sample collection site | ||||

| Respiratory tract | 14 (28.0) | 29 (29.0) | 0.51 | 0.972 |

| Blood | 13 (26.0) | 27 (27.0) | ||

| Urinary tract | 12 (24.0) | 23 (23.0) | ||

| Soft tissue | 6 (12.0) | 14 (14.0) | ||

| Abdomen | 5 (10.0) | 7 (7.0) | ||

| Genus and species | ||||

| Enterobacter cloacae | 23 (46.0) | 42 (42.0) | 2.63 | 0.977 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.0) | ||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 12 (24.0) | 23 (23.0) | ||

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 5 (10.0) | 11 (11.0) | ||

| Citrobacter freundii | 5 (10.0) | 10 (10.0) | ||

| Serratia marcescens | 2 (2.0) | 4 (4.0) | ||

| Raoultella ornithinolytica | 1 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | ||

| Escherichia coli | 1 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | ||

| Raoultella planticola | 1 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | ||

ERE: ertapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae; ESE: ertapenem-susceptible enterobacteriaceae.

In the ERE group, the antibiotics with greatest in vitro activity were amikacin (86.0% of susceptibility), tigecycline (85.4%), ciprofloxacin (62.0%) and gentamicin (54.0%). Decreased susceptibility to all β-lactams, including other third- and fourth-generation carbapenems and cephalosporins was observed. In 38 isolates (88.0%) a positive result was obtained in the modified Hodge test.

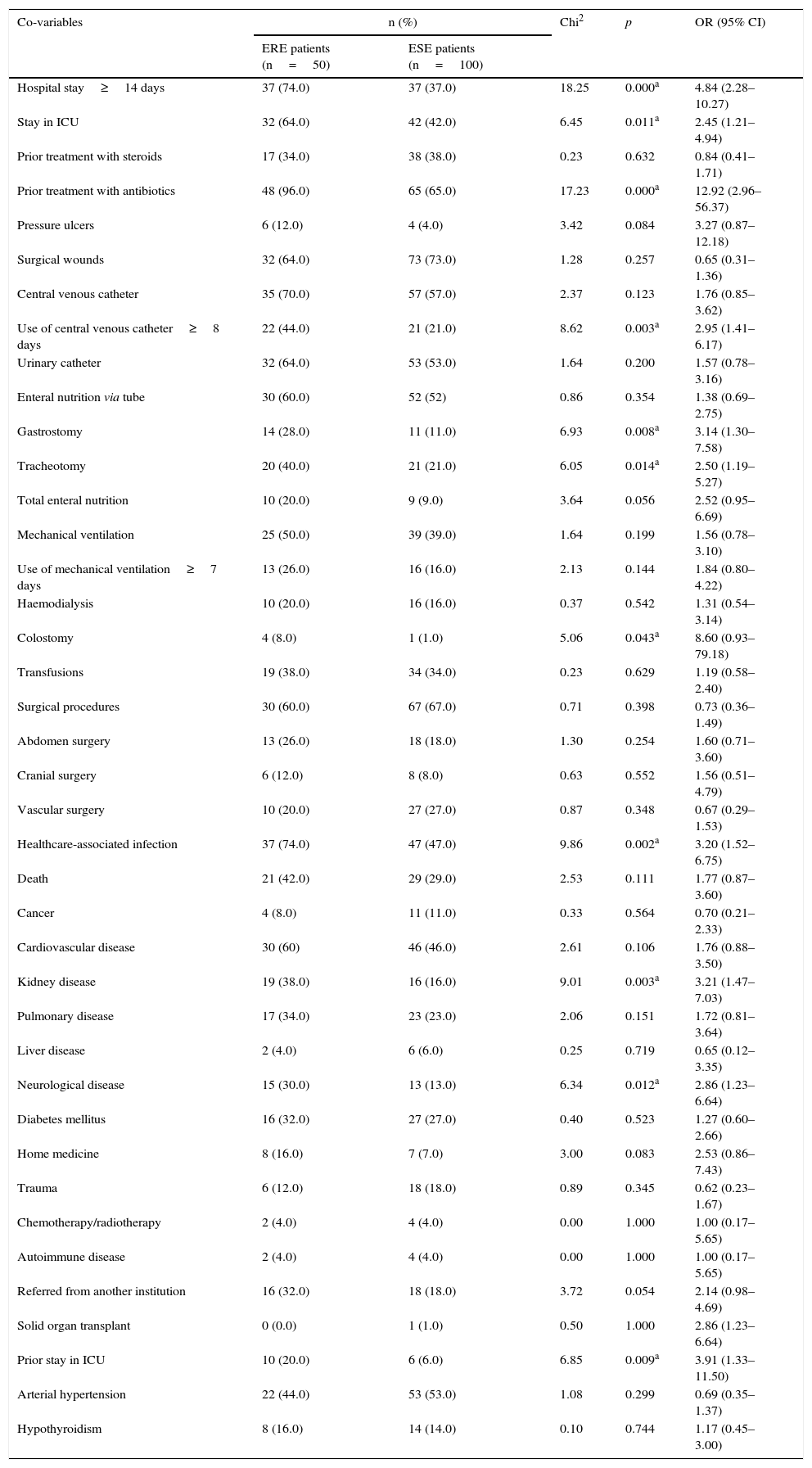

The average age of the cases was 69.5 years, and 67.5 years in the controls. No differences were found between the groups regarding age (p=0.199) or the proportion of male patients (p=0.164). In the group of cases, a larger proportion of individuals with a history of prior hospitalisation in intensive care units was observed (OR 3.91; 95% CI 1.33–11.50; p=0.009), as well as kidney disease (OR 3.21; 95% CI 1.47–7.03; p=0.003) and neurological disease (OR 2.86; 95% CI 1.23–6.64; p=0.012) (Table 2).

Clinical and variable factors related to hospitalisation, procedures, and invasive devices at the time of isolation of ertapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae and ertapenem-susceptible enterobacteriaceae.

| Co-variables | n (%) | Chi2 | p | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERE patients (n=50) | ESE patients (n=100) | ||||

| Hospital stay≥14 days | 37 (74.0) | 37 (37.0) | 18.25 | 0.000a | 4.84 (2.28–10.27) |

| Stay in ICU | 32 (64.0) | 42 (42.0) | 6.45 | 0.011a | 2.45 (1.21–4.94) |

| Prior treatment with steroids | 17 (34.0) | 38 (38.0) | 0.23 | 0.632 | 0.84 (0.41–1.71) |

| Prior treatment with antibiotics | 48 (96.0) | 65 (65.0) | 17.23 | 0.000a | 12.92 (2.96–56.37) |

| Pressure ulcers | 6 (12.0) | 4 (4.0) | 3.42 | 0.084 | 3.27 (0.87–12.18) |

| Surgical wounds | 32 (64.0) | 73 (73.0) | 1.28 | 0.257 | 0.65 (0.31–1.36) |

| Central venous catheter | 35 (70.0) | 57 (57.0) | 2.37 | 0.123 | 1.76 (0.85–3.62) |

| Use of central venous catheter≥8 days | 22 (44.0) | 21 (21.0) | 8.62 | 0.003a | 2.95 (1.41–6.17) |

| Urinary catheter | 32 (64.0) | 53 (53.0) | 1.64 | 0.200 | 1.57 (0.78–3.16) |

| Enteral nutrition via tube | 30 (60.0) | 52 (52) | 0.86 | 0.354 | 1.38 (0.69–2.75) |

| Gastrostomy | 14 (28.0) | 11 (11.0) | 6.93 | 0.008a | 3.14 (1.30–7.58) |

| Tracheotomy | 20 (40.0) | 21 (21.0) | 6.05 | 0.014a | 2.50 (1.19–5.27) |

| Total enteral nutrition | 10 (20.0) | 9 (9.0) | 3.64 | 0.056 | 2.52 (0.95–6.69) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 25 (50.0) | 39 (39.0) | 1.64 | 0.199 | 1.56 (0.78–3.10) |

| Use of mechanical ventilation≥7 days | 13 (26.0) | 16 (16.0) | 2.13 | 0.144 | 1.84 (0.80–4.22) |

| Haemodialysis | 10 (20.0) | 16 (16.0) | 0.37 | 0.542 | 1.31 (0.54–3.14) |

| Colostomy | 4 (8.0) | 1 (1.0) | 5.06 | 0.043a | 8.60 (0.93–79.18) |

| Transfusions | 19 (38.0) | 34 (34.0) | 0.23 | 0.629 | 1.19 (0.58–2.40) |

| Surgical procedures | 30 (60.0) | 67 (67.0) | 0.71 | 0.398 | 0.73 (0.36–1.49) |

| Abdomen surgery | 13 (26.0) | 18 (18.0) | 1.30 | 0.254 | 1.60 (0.71–3.60) |

| Cranial surgery | 6 (12.0) | 8 (8.0) | 0.63 | 0.552 | 1.56 (0.51–4.79) |

| Vascular surgery | 10 (20.0) | 27 (27.0) | 0.87 | 0.348 | 0.67 (0.29–1.53) |

| Healthcare-associated infection | 37 (74.0) | 47 (47.0) | 9.86 | 0.002a | 3.20 (1.52–6.75) |

| Death | 21 (42.0) | 29 (29.0) | 2.53 | 0.111 | 1.77 (0.87–3.60) |

| Cancer | 4 (8.0) | 11 (11.0) | 0.33 | 0.564 | 0.70 (0.21–2.33) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 30 (60) | 46 (46.0) | 2.61 | 0.106 | 1.76 (0.88–3.50) |

| Kidney disease | 19 (38.0) | 16 (16.0) | 9.01 | 0.003a | 3.21 (1.47–7.03) |

| Pulmonary disease | 17 (34.0) | 23 (23.0) | 2.06 | 0.151 | 1.72 (0.81–3.64) |

| Liver disease | 2 (4.0) | 6 (6.0) | 0.25 | 0.719 | 0.65 (0.12–3.35) |

| Neurological disease | 15 (30.0) | 13 (13.0) | 6.34 | 0.012a | 2.86 (1.23–6.64) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (32.0) | 27 (27.0) | 0.40 | 0.523 | 1.27 (0.60–2.66) |

| Home medicine | 8 (16.0) | 7 (7.0) | 3.00 | 0.083 | 2.53 (0.86–7.43) |

| Trauma | 6 (12.0) | 18 (18.0) | 0.89 | 0.345 | 0.62 (0.23–1.67) |

| Chemotherapy/radiotherapy | 2 (4.0) | 4 (4.0) | 0.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 (0.17–5.65) |

| Autoimmune disease | 2 (4.0) | 4 (4.0) | 0.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 (0.17–5.65) |

| Referred from another institution | 16 (32.0) | 18 (18.0) | 3.72 | 0.054 | 2.14 (0.98–4.69) |

| Solid organ transplant | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0.50 | 1.000 | 2.86 (1.23–6.64) |

| Prior stay in ICU | 10 (20.0) | 6 (6.0) | 6.85 | 0.009a | 3.91 (1.33–11.50) |

| Arterial hypertension | 22 (44.0) | 53 (53.0) | 1.08 | 0.299 | 0.69 (0.35–1.37) |

| Hypothyroidism | 8 (16.0) | 14 (14.0) | 0.10 | 0.744 | 1.17 (0.45–3.00) |

CI: confidence interval; ERE: ertapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae; ESE: ertapenem-susceptible enterobacteriaceae; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; OR: odds ratio.

In addition, in the group of cases, a greater proportion of subjects were found who were hospitalised at the time of isolation >13 days (OR 4.84; 95% CI 2.28–10.27; p=0.000), hospitalised in intensive care units (OR 2.45; 95% CI 1.21–4.94; p=0.011), using central venous catheter for ≥8 days (OR 2.95; 95% CI 1.41–6.17; p=0.003) and having had gastrostomy, tracheotomy or colostomy, as well as having received antibiotic treatment prior to the isolation.

In the bivariate analysis it was also observed that prior exposure to carbapenems (OR 6.74; 95% CI 3.13–14.51; p=0.000), cefepime (OR 5.26; 95% CI 1.29–21.33; p=0.016) and the combination β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor, especially piperacillin/tazobactam (OR 2.62; 95% CI 1.28–5.35, p=0.007), was more frequent in patients with ERE infections. No differences were found in the proportion exposed to fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides or aztreonam.

The multivariate analysis demonstrated that prior exposure to cefepime (OR 6.46; 95% CI 1.08–38.38) and to carbapenems (OR 3.43; 95% CI 1.08–10.87) were the only factors associated with ERE infection in this population.

DiscussionCarbapenem resistance is a growing phenomenon and represents a threat to public health, since it reduces therapeutic possibilities to treat germ-resistant infections.7 This problem is common in hospital institutions in various regions of the world, and Colombia in particular has been categorised as endemic for carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae.8

In this study, it was found that the factors that best explain ERE infection are prior exposure to carbapenems and prior exposure to cefepime. This resistance can be acquired through mutations in the genetic material or through acquisition of genes from other bacteria.9 Subsequent exposure to the antibiotic selects the bacterial subpopulation that can express the resistance mechanism, converting it into the predominant genotype. Prior exposure to carbapenems has been reported in other studies as a factor associated with infection by bacteria resistant to these antibiotics.10,11

Also, the relationship found between the use of cefepime and ERE infection has been reported in other research studies.10,12 One explanation for this is that given that the carbapenemase enzymes confer high levels of resistance to β-lactams, including cephalosporins, it is plausible that selective pressure induced by the use thereof causes the emergence of bacterial populations that express genes encoding for carbapenem resistance through this mechanism.

Although in this study the involved ertapenem resistance mechanism was not confirmed via molecular or phenotypic tests, this is probably due to production of carbapenemase enzymes, since 88% of the isolates returned positive results in the modified Hodge test, which has a sensitivity and specificity exceeding 90% to detect KPC-type carbapenemase-producing isolates.5 Furthermore, this is the mechanism that has been found most frequently conferring resistance to carbapenems in Colombia.1–3

The limitations of this study arise from its retrospective nature, given that the molecular identification of the carbapenem-resistance mechanisms was not performed nor were additional phenotypic tests carried out. Therefore, the ertapenem resistance could be mediated, either by the production of carbapenemase enzymes,13 or by a combination of the overproduction of β-lactamases (extended-spectrum β-lactamases or AmpC enzymes) and concomitant mutations, such as those that lead to the loss of porins, causing a defect in permeability14 and that could return false positives in the modified Hodge test.15 The role of patient-to-patient transmission of these micro-organisms was not evaluated either. This is a situation in which the relevance of prior antibiotic exposure as a risk factor could be less. In addition, colonisation prior to ERE infection was not analysed in this study.

The findings of this study highlight the importance of antibiotic management programmes and the need for future research studies that allow for greater understanding of the growing problem of antibiotic resistance, as well as for the design of prevention and control strategies.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest, with the exception of Indira Berrio, who has been a speaker at conferences and has advised the pharmaceutical companies Pfizer, MSD and Bayer.

Please cite this article as: Maldonado N, Castro B, Berrio I, Manjarrés M, Robledo C, Robledo J. Resistencia a ertapenem en 2 instituciones hospitalarias de alto nivel de complejidad: microbiología, epidemiología y factores de riesgo. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:509–513.