Integrase inhibitors (INI) and especially dolutegravir (DTG) are placed as a first-line antiretroviral treatment for their efficacy and safety. Although in the pivotal trials the rate of adverse effects (AEs) was low (2–3%), in real-life studies it appears to be higher, especially neuropsychiatric AEs. The objective is to determine the percentage of AEs and discontinuation of DTG in our site and the relationship with the psychiatric background.

MethodsRetrospective descriptive study of patients starting DTG from 2015 to 2017. Discontinuation of treatment, adverse effects and previous psychiatric pathology were recorded. Follow-up is carried out since the beginning of the treatment and hospitalizations, emergency room (ER) visits and primary care (PC) were registered. The study was authorizedby the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of Aragon.

Results283 patients were included, between 11 and 87 years old, 70% male. 21% were naive. 24% of the patients discontinued treatment with DTG, 10% due to AEs. Neuropsychiatric AEs were was detected in 5%. This group of patients had a more frequent previous psychiatric history (62 vs 41%; p=0.002) than the ongoing treatment group and they needed more visits to PC (18.8 vs 8.4% p=0.016), ER (8,7 vs 3.3% p=0.061) and in one case even hospitalization due to AE.

ConclusionPatients who discontinued treatment with DTG had more psychiatric history. Although more studies are required, it is necessary to assess this background before starting treatment with INI. Symptoms such as anxiety, insomnia, depression can be DTG AEs more frequently than expected. Being identified by PC and emergency physicians could avoid the unnecessary prescription of other medications.

Los inhibidores de integrasa (INI) y especialmente dolutegravir (DTG) son el tratamiento de primera línea antirretroviral por su eficacia y seguridad. Aunque en los ensayos pivotales la tasa de efectos adversos (EA) era baja (2–3%), en los estudios de vida real parece ser mayor, especialmente los EA neuropsiquiátricos. El objetivo fue determinar el porcentaje de EA y discontinuación de DTG en nuestro centro y la relación con los antecedentes psiquiátricos.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo retrospectivo de pacientes que iniciaron DTG entre 2015−2017. Se registraron: discontinuación, efectos adversos y patología psiquiátrica. Se realizó seguimiento desde inicio del fármaco y se registraron las hospitalizaciones, visitas a urgencias y atención primaria (AP). Fue autorizado por el Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica de Aragón.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 283 pacientes, entre 11–87 años, 70% varones. El 21% naive. Discontinuó tratamiento con DTG el 24%, 10% por EA. Se detectó un 5% de EA neuropsiquiátricos. Este grupo tenía más antecedentes psiquiátricos (62 vs 41%; p=0,002) que el de pacientes que continuaron el tratamiento, y precisaron más visitas en AP (18,8 vs 8,4% p=0,016), urgencias (8,7 vs 3,3% p=0,061).

ConclusiónLos pacientes que discontinuaron tratamiento con DTG tenían más antecedentes psiquiátricos. Por lo que, aunque se precisan más estudios, sería necesario valorar este antecedente previamente al tratamiento con INI. Síntomas como ansiedad, insomnio, depresión pueden ser EA de DTG en una frecuencia mayor a la esperada. Ser identificados por los médicos de AP y urgencias podría evitar una cascada de prescripción innecesaria.

The incorporation of integrase inhibitors (INIs) into human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) treatment has brought about a highly significant improvement in the safety and effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (ART). That is why it is the first-line initial ART option in naive patients.1,2 Specifically, dolutegravir (DTG) showed greater efficacy compared to other initial ARTs, such as efavirenz, darunavir co-administered with ritonavir, and atazanavir co-administered with ritonavir in females.3–5 Even among INIs, according to a meta-analysis sponsored by the World Health Organization, DTG stands as the most effective (followed by raltegravir and, after that, elvitegravir/cobicistat), though the analysis only included regimens of elvitegravir/cobicistat co-formulated with emtricitabine/tenofovir,6 presenting a low virological failure rate, high genetic barrier, low potential for interactions, and high central nervous system penetration.7 A fourth INI, bictegravir, has recently been marketed in Spain.

INIs are considered to be the safest family of drugs, given their low rate of adverse effects (AEs). In pivotal trials of DTG, the rate of serious AEs was around 9%–11%,4,7 and only led to suspension of treatment in 2% of patients in the SINGLE, SPRING-2 and FLAMINGO trials3,4,8 and in 3% of patients in the VIKING-3 and SAILING trials.9,10

However, since it was placed on the market in 2014, a higher rate of AEs, especially neuropsychiatric ones, has been reported (3.4%–6%)11–13 in retrospective studies and case series compared to pivotal trials, on including DTG in clinical practice.14,15 The neuropsychiatric adverse effects (NPAEs) with the highest incidence are: insomnia and sleep disturbances, anxiety, depression and psychosis.16 Factors that could predispose an individual to the onset of this type of AE include female sex, age over 65 years15 and inclusion of abacavir in the ART regimen.17 Nonetheless, these results have not been replicated in all studies, which calls for a more comprehensive analysis of data obtained in clinical practice.

The objectives of this study are to establish the rate of DTG suspension and the reasons for this suspension in our setting, and to determine what could be considered risk factors for developing NPAEs, such as the patient's medical history in general and psychiatric history in particular.

MethodsA retrospective descriptive study conducted at a tertiary referral hospital that enrolled patients who started treatment with DTG between March 2015 and September 2017 (in the form of either of the 2 medicinal products marketed to date: Tivicay® or Triumeq®) through the electronic prescription programme of the Hospital Pharmacy Department. Patients were divided into 2 groups: those who suspended treatment with DTG and those who did not. Switching from one commercial form of DTG to another (from Tivicay® to Triumeq® or vice versa) was not considered suspending treatment.

The following data in the medical record were reviewed: age, baseline CD4 count, baseline viral load, sex, ethnicity, ART status (naive patient or prior ART), antiretroviral drugs accompanying DTG, duration of treatment, and psychiatric history or prior use of psychiatric drugs. Retrospective patient follow-up was conducted from the time the drug was prescribed until January 2018, by means of electronic medical record consultations and telephone calls when necessary. The following were recorded: AEs attributed to DTG, need for medical care for psychiatric reasons while taking DTG (primary care [PC], emergency care or hospital admission), treatment suspension and, where applicable, reason for switching and subsequent ART.

Statistical analysis was performed with the IBM® SPSS® Statistics software program, ver. 19. Quantitative variables were presented in terms of mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range. Qualitative variables were presented in terms of frequency and percentage. Comparison of quantitative variables between independent groups was performed using Student's t-test when they were parametric and the Mann–Whitney U test when they were non-parametric. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test. The study was authorised by the Aragón Independent Ethics Committee.

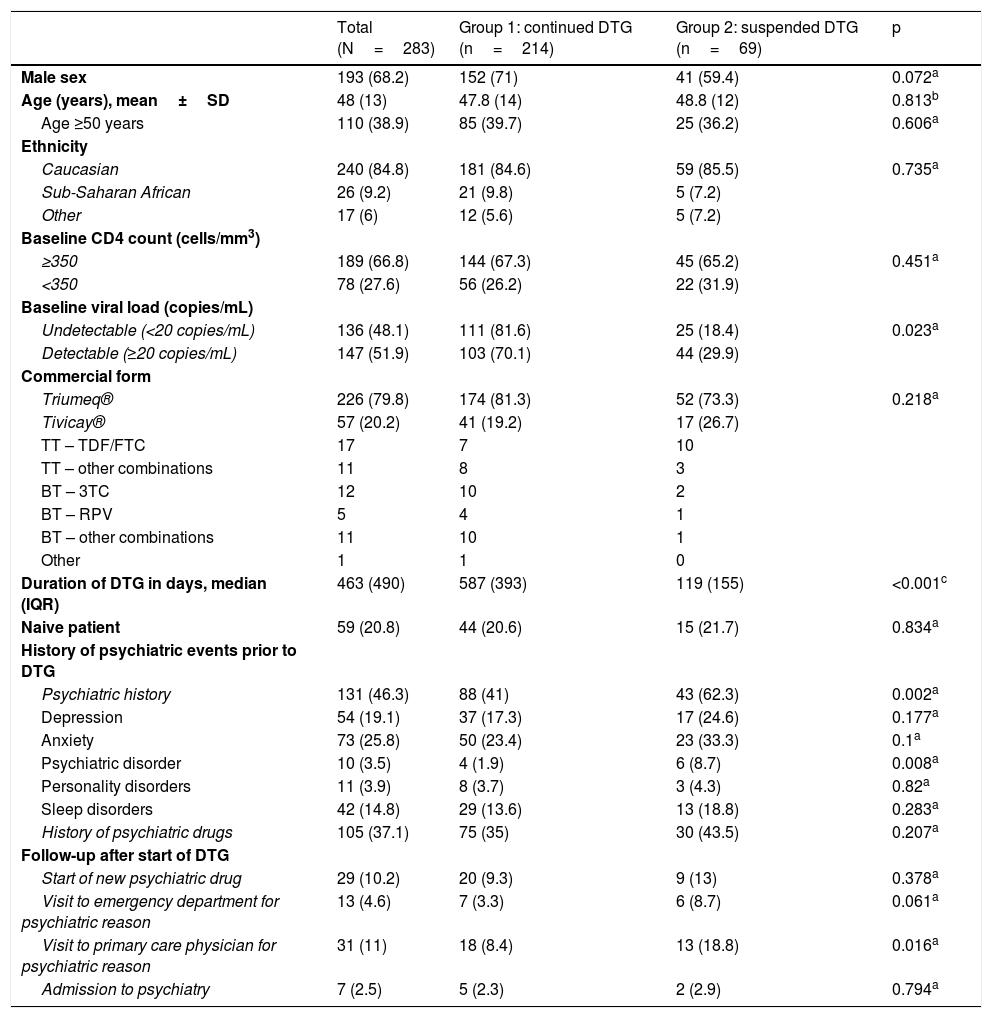

ResultsA total of 283 patients were enrolled; their ages ranged from 11 to 87 years, and 70% were male. Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the patients and those of each group. The two groups were comparable in terms of demographics. The median number of days of treatment with DTG was 463, and was significantly lower in the group that suspended said treatment (p<0.001).

Patients’ characteristics, psychiatric history and follow-up after starting dolutegravir.

| Total (N=283) | Group 1: continued DTG (n=214) | Group 2: suspended DTG (n=69) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 193 (68.2) | 152 (71) | 41 (59.4) | 0.072a |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 48 (13) | 47.8 (14) | 48.8 (12) | 0.813b |

| Age ≥50 years | 110 (38.9) | 85 (39.7) | 25 (36.2) | 0.606a |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 240 (84.8) | 181 (84.6) | 59 (85.5) | 0.735a |

| Sub-Saharan African | 26 (9.2) | 21 (9.8) | 5 (7.2) | |

| Other | 17 (6) | 12 (5.6) | 5 (7.2) | |

| Baseline CD4 count (cells/mm3) | ||||

| ≥350 | 189 (66.8) | 144 (67.3) | 45 (65.2) | 0.451a |

| <350 | 78 (27.6) | 56 (26.2) | 22 (31.9) | |

| Baseline viral load (copies/mL) | ||||

| Undetectable (<20 copies/mL) | 136 (48.1) | 111 (81.6) | 25 (18.4) | 0.023a |

| Detectable (≥20 copies/mL) | 147 (51.9) | 103 (70.1) | 44 (29.9) | |

| Commercial form | ||||

| Triumeq® | 226 (79.8) | 174 (81.3) | 52 (73.3) | 0.218a |

| Tivicay® | 57 (20.2) | 41 (19.2) | 17 (26.7) | |

| TT – TDF/FTC | 17 | 7 | 10 | |

| TT – other combinations | 11 | 8 | 3 | |

| BT – 3TC | 12 | 10 | 2 | |

| BT – RPV | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| BT – other combinations | 11 | 10 | 1 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Duration of DTG in days, median (IQR) | 463 (490) | 587 (393) | 119 (155) | <0.001c |

| Naive patient | 59 (20.8) | 44 (20.6) | 15 (21.7) | 0.834a |

| History of psychiatric events prior to DTG | ||||

| Psychiatric history | 131 (46.3) | 88 (41) | 43 (62.3) | 0.002a |

| Depression | 54 (19.1) | 37 (17.3) | 17 (24.6) | 0.177a |

| Anxiety | 73 (25.8) | 50 (23.4) | 23 (33.3) | 0.1a |

| Psychiatric disorder | 10 (3.5) | 4 (1.9) | 6 (8.7) | 0.008a |

| Personality disorders | 11 (3.9) | 8 (3.7) | 3 (4.3) | 0.82a |

| Sleep disorders | 42 (14.8) | 29 (13.6) | 13 (18.8) | 0.283a |

| History of psychiatric drugs | 105 (37.1) | 75 (35) | 30 (43.5) | 0.207a |

| Follow-up after start of DTG | ||||

| Start of new psychiatric drug | 29 (10.2) | 20 (9.3) | 9 (13) | 0.378a |

| Visit to emergency department for psychiatric reason | 13 (4.6) | 7 (3.3) | 6 (8.7) | 0.061a |

| Visit to primary care physician for psychiatric reason | 31 (11) | 18 (8.4) | 13 (18.8) | 0.016a |

| Admission to psychiatry | 7 (2.5) | 5 (2.3) | 2 (2.9) | 0.794a |

3TC: lamivudine; BT: bitherapy; DTG: dolutegravir; IQR: interquartile range; RPV: rilpivirine; SD: standard deviation; TDF/FTC: tenofovir/emtricitabine; TT: triple therapy.

Data are expressed in terms of n (%), except where otherwise indicated.

Of the entire sample, 21% were naive patients; all other patients had received ART with triple therapy with protease inhibitors (75; 33%), non-analogues (54; 24%) and other integrase inhibitors (42; 19%). Other ART regimens were monotherapy with darunavir (15; 6,7%), monotherapy with lopinavir (9; 4%), bitherapy (16; 7%) and other less common regimens (12; 5,4%). One patient had not been taking any prior treatment, having stopping ART. The most common treatment combination along with DTG was abacavir/lamivudine (79.9%; 226 patients) (Table 1).

Treatment with DTG was suspended in 69 patients (24.4%); this group more often had a history of psychiatric events (62 versus 41%; p=0.002) and a higher frequency of psychotic disorders (8.7 versus 1.9%; p=0.008). There was also a trend towards more often presenting depression, anxiety, personality disorders and sleep disorders, though differences were not statistically significant (Table 1). No differences between baseline CD4 count (<350 cells/mm3), ethnicity, age >50 years, commercial form (Tivicay®/Triumeq®) or ART status (naive/pretreated) were found between the group that suspended treatment and the group that did not. Differences were found, however, in detectable versus undetectable baseline viral load; 29.9% of patients with a detectable baseline viral load versus 18.38% of patients with an undetectable baseline viral load suspended treatment (p=0.024). It should be noted that the relative risk of suspending treatment was 1.46 times higher (0.971–2.21; p=0.072) in women versus men, although statistical significance was not achieved.

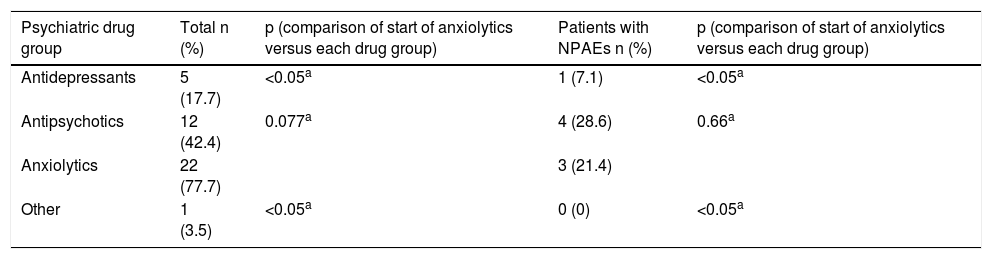

Patients who suspended DTG more often visited their PC physician with psychiatric symptoms (18.8 versus 8.4%; p=0.016) and the emergency department (8.7 versus 3.3%; p=0.061) compared to the other group. In both groups, though there were no statistically significant differences, at least one new psychiatric drug had to be started while taking DTG (anxiolytics 77.7%, antipsychotics 42.4%, antidepressants 17.7% and other 3.5%) (Table 2), and 7 patients had to be admitted to hospital in a psychiatric unit owing to decompensation of their underlying psychiatric disease (Table 1). Notably, the majority of anxiolytics were prescribed for insomnia.

Psychiatric drugs started following change in antiretroviral treatment to dolutegravir.

| Psychiatric drug group | Total n (%) | p (comparison of start of anxiolytics versus each drug group) | Patients with NPAEs n (%) | p (comparison of start of anxiolytics versus each drug group) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants | 5 (17.7) | <0.05a | 1 (7.1) | <0.05a |

| Antipsychotics | 12 (42.4) | 0.077a | 4 (28.6) | 0.66a |

| Anxiolytics | 22 (77.7) | 3 (21.4) | ||

| Other | 1 (3.5) | <0.05a | 0 (0) | <0.05a |

NPAEs: neuropsychiatric adverse effects.

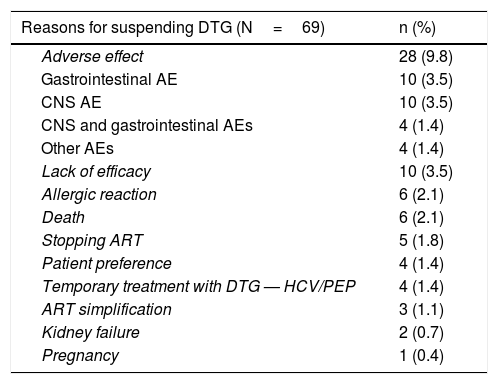

The most common cause of suspension of this drug was AEs: 28 patients (9.89%). The predominant AEs were gastrointestinal (abdominal pain, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting) and neuropsychiatric. A rate of NPAEs of 4.9% was detected; these were: anxiety, depression, insomnia, nightmares, behavioural disorders and, in one case, autolytic attempt. Other reasons for suspension are listed in Table 3. In most cases in which suspension due to lack of efficacy was recorded, said lack of efficacy corresponded to sustained low-level viraemia. Of the 4 patients who took DTG on a temporary basis, 3 started it as simultaneous treatment for hepatitis C to prevent interactions, and then resumed their usual treatment. In the other case, DTG was included in a post-exposure prophylactic regimen, and was suspended after 28 days of treatment.

Reasons for suspending dolutegravir.

| Reasons for suspending DTG (N=69) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Adverse effect | 28 (9.8) |

| Gastrointestinal AE | 10 (3.5) |

| CNS AE | 10 (3.5) |

| CNS and gastrointestinal AEs | 4 (1.4) |

| Other AEs | 4 (1.4) |

| Lack of efficacy | 10 (3.5) |

| Allergic reaction | 6 (2.1) |

| Death | 6 (2.1) |

| Stopping ART | 5 (1.8) |

| Patient preference | 4 (1.4) |

| Temporary treatment with DTG — HCV/PEP | 4 (1.4) |

| ART simplification | 3 (1.1) |

| Kidney failure | 2 (0.7) |

| Pregnancy | 1 (0.4) |

AE: adverse effect; ART: antiretroviral treatment; CNS: central nervous system; DTG: dolutegravir; HCV: hepatitis C virus; PEP: post-exposure prophylaxis.

Among the 69 patients who suspended DTG, 11 (16%) did not start a new ART (death or withdrawal from treatment and follow-up). Of the 58 patients who started treatment subsequently to DTG, 12 (20.6%) returned to their prior treatment.

DiscussionIn this study, rates of treatment suspension due to AEs with DTG were 3–5 times higher than those found in pivotal clinical trials (9.8% versus 2%–3%), especially gastrointestinal AEs and those affecting the central nervous system. This supports findings in clinical practice regarding DTG use outside of a clinical trial setting. Possible reasons for these discrepancies include patient screening in clinical trials with rigorous inclusion criteria which, in many cases, do not apply to real-life clinical practice.

The high rate of naive patients in the study (21%) is explained by the January 2014 change to the Spanish national recommendations in the Grupo de Estudio de SIDA [Spanish AIDS Study Group] (GeSIDA) guidelines, which positioned INIs as preferential initial ART, though the drug was not marketed for use in clinical practice until 2015.18

Moreover, in our case series, the rate of suspension due to AEs was twice that of other real-life study cohorts, such as a Hospital Ramón y Cajal [Ramón y Cajal Hospital] cohort (4.3%)19 and a Swiss cohort (5.7%).20 It was, however, consistent with other published studies having reported rates of suspension due to AEs of 7.6%–13.7% (with 5.6%–9.9% due to NPAEs).14,16,21,22 Risk factors for DTG suspension have been reported in the literature 14,16,21,23 (baseline CD4 count <350, inclusion of abacavir in treatment, age >50 years, sub-Saharan African ethnicity, female sex and Tivicay® commercial form), though there were no significant differences in these factors in our study. In our study, patients with a detectable baseline viral load suspended the treatment more frequently.

Most of these series reported no baseline psychiatric disease history, even though psychiatric comorbidities are much more common in the population with HIV than in the general population. Anxiety has been reported in up to 30% of cases, depression in 50% and insomnia in up to 70%.24 Our study population, 46% of patients had a history of psychiatric events; this was slightly higher than the 38% reported in the Observational Pharmaco-Epidemiology Research and Analysis (OPERA) registry.24 In our study, as many as 62% of patients in the group that suspended treatment with DTG had a history of psychiatric events.

The high rate of patients with a history of neuropsychiatric events, predominantly in the group that suspended DTG, as well as suspension due to NPAEs, up to 5% in our study, appear to point to a relationship between DTG use and a higher incidence of NPAEs. However, this might also have stemmed from not controlling for confounding factors, since, for example, underlying psychiatric disease itself could lead to treatment suspension and not the other way round.

During treatment with DTG, patients who suspended said treatment visited their PC physician and the emergency department more frequently due to their psychiatric disorder, resulting, in many cases, in adding another psychiatric drug to their usual medication owing to a failure to relate it to their change in medication. Interestingly, a large percentage of patients who did not suspend treatment with DTG had to start at least one new psychiatric drug during treatment with DTG; this could be attributed to the onset of an NPAE not detected as such and treated symptomatically.

Scheduled visits to infectious disease clinics have been spaced out due to good tolerance of new treatments in recent years. This may have contributed to delays in the detection of these AEs by infectious disease specialists, and to increased use of other healthcare services. Patients, PC physicians and emergency physicians would need to be educated in the most common AEs of these drugs, so that they can be detected early. Hospital pharmacists could also play a more prominent role in this detection, as patients regularly visit hospital pharmacy departments to pick up medication.

The main limitations of this study were that it was a single-centre study with a moderate sample size, and hence its findings may not be generalisable, and that, as it was a descriptive study, it was not possible to control for confounding factors. Another notable limitation of our study was that we could not specify the temporal relationship between visits to emergency departments, PC physicians and infectious disease specialists, as electronic medical records were not fully digitalised. Finally, another limitation of our study worth mentioning is that, owing to the study's initial design, there was no follow-up of AEs after suspension of DTG, and, as a result, we have no information on the courses of said AEs after DTG was suspended. No multivariate analysis to identify risk factors for suspending treatment due to NPAEs was performed due to the limited sample size of this subgroup of patients. Notwithstanding this, our study had certain strengths, such as its recording of baseline psychiatric disease and its consideration of subsequent medical visits and psychiatric drug prescriptions, which placed limits on the underestimation that has been cited in studies in other, broader cohorts.

Despite its limitations, our study showed a link between DTG use and NPAEs that was stronger than expected. More extensive studies will be needed in order to firmly establish this link, especially in patients with underlying psychiatric disorders.

In conclusion, although more real-life data are needed to arrive at conclusive results, there is a link between the presence of underlying psychiatric diseases and suspension of the use of DTG for the treatment of HIV. Therefore, establishing psychiatric diseases as a clinical criterion before starting ART with this drug, and most likely those of the same family, should be considered, at least until more data are available on bictegravir. In addition, the education of patients and healthcare personnel who are not infectious disease specialists (PC physicians, emergency department staff and hospital pharmacy staff) is essential in determining the causal relationship between DTG use and non-specific symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, insomnia, depression and anxiety. This could prevent unnecessary admissions and prescriptions, as well as suspensions of ART and the consequences thereof for public health.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Povar-Echeverría M, Comet-Bernad M, Gasso-Sánchez A, Ger-Buil A, Navarro-Aznarez H, Martínez-Álvarez R, et al. Efectos adversos neuropsiquiátricos de dolutegravir en la práctica clínica real. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:78–82.