Bartonella henselae causes cat scratch disease (CSD), spread by a cat scratch or bite. Cats are its main reservoir. This sometimes results in optic neuritis or neuroretinitis.

ObjectiveTo review these conditions in Gipuzkoa (Spain), 2014−2019.

MethodsA retrospective review of serology registries and clinical registries, selecting those with consistent clinical signs, contact with cats and positive serology for B. henselae (IgG-IFA ≥1/256).

ResultsSixty-four patients had CSD. Of these, one had optic neuritis and 3 had neuroretinitis (4/64; 6.3%). In 3 patients, flu-like symptoms preceded eye symptoms. Two suffered from loss of visual acuity at discharge, despite prolonged treatment with antibiotics and corticosteroids.

ConclusionOptic neuritis and neuroretinitis caused by B. henselae are severe complications with a non-negligible incidence among patients with CSD in Gipuzkoa. We recommend ruling out CSD in patients with symptoms of optic neuritis or neuroretinitis (sudden vision loss, etc.) and contact with cats.

Bartonella henselae causa la enfermedad por arañazo de gato (EAG), transmitida por arañazo o mordedura de gato, su principal reservorio. En ocasiones produce neuritis óptica o neurorretinitis.

ObjetivoRevisar estas patologías en Gipuzkoa (España), 2014−2019.

MétodosRevisión retrospectiva de registros serológicos y clínicos, seleccionando aquellos con manifestaciones clínicas compatibles, contacto con gatos y serología positiva para B. henselae (IFI-IgG ≥1/256).

ResultadosSesenta y cuatro pacientes presentaron EAG; entre estos, uno tenía neuritis óptica y 3, neurorretinitis (4/64, 6,3%). En 3 casos un cuadro pseudogripal precedió a los síntomas oculares; 2 presentaron pérdida de agudeza visual al alta, a pesar del tratamiento prolongado con antibióticos y corticoides.

ConclusiónLa neuritis óptica y la neurorretinitis por B. henselae son complicaciones graves que presentan una incidencia no despreciable entre los pacientes con EAG de Gipuzkoa. Recomendamos descartar la EAG en pacientes con síntomas de neuritis óptica o neurorretinitis (pérdida brusca de visión, etc.) y contacto con gatos.

Bartonella henselae is the aetiological agent of cat-scratch disease (CSD), a usually-benign and self-limiting infection characterised by regional lymphadenopathy associated with influenza-like symptoms1,2, transmitted through the scratches or bites of cats, its main reservoir2–4. Less frequently, extranodal manifestations can present1,4, with the eye being the organ most often affected5.

Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome is the most typical ocular manifestation.2,3,5 Other reported ocular manifestations are uveitis4, neuroretinitis1–4, inflammatory optic nerve oedema and retinal vessel occlusion1,4,5. Neuroretinitis is the most common complication of the infection and, in turn, B. henselae is the most common infectious cause of neuroretinitis3.

The objective of this work was to describe cases of involvement of the posterior segment of the eye associated with B. henselae infection detected between 2014 and 2019 at the Hospital Universitario Donostia [Donostia University Hospital], which covers the majority of the population of Gipuzkoa (~600,000 inhabitants).

MethodsPatients with positive serology for B. henselae were obtained from the laboratory’s records. Those patients with specific IgG ≥1/256 (Bartonella IFA, Focus Diagnostics) were considered positive. The corresponding medical records were reviewed and those patients with clinical manifestations compatible with involvement of the posterior segment of the eye, a history of contact with cats and serology results negative for cytomegalovirus, Toxoplasma, HIV, syphilis and Borrelia burgdorferi were selected. The study was approved by the Gipuzkoa Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

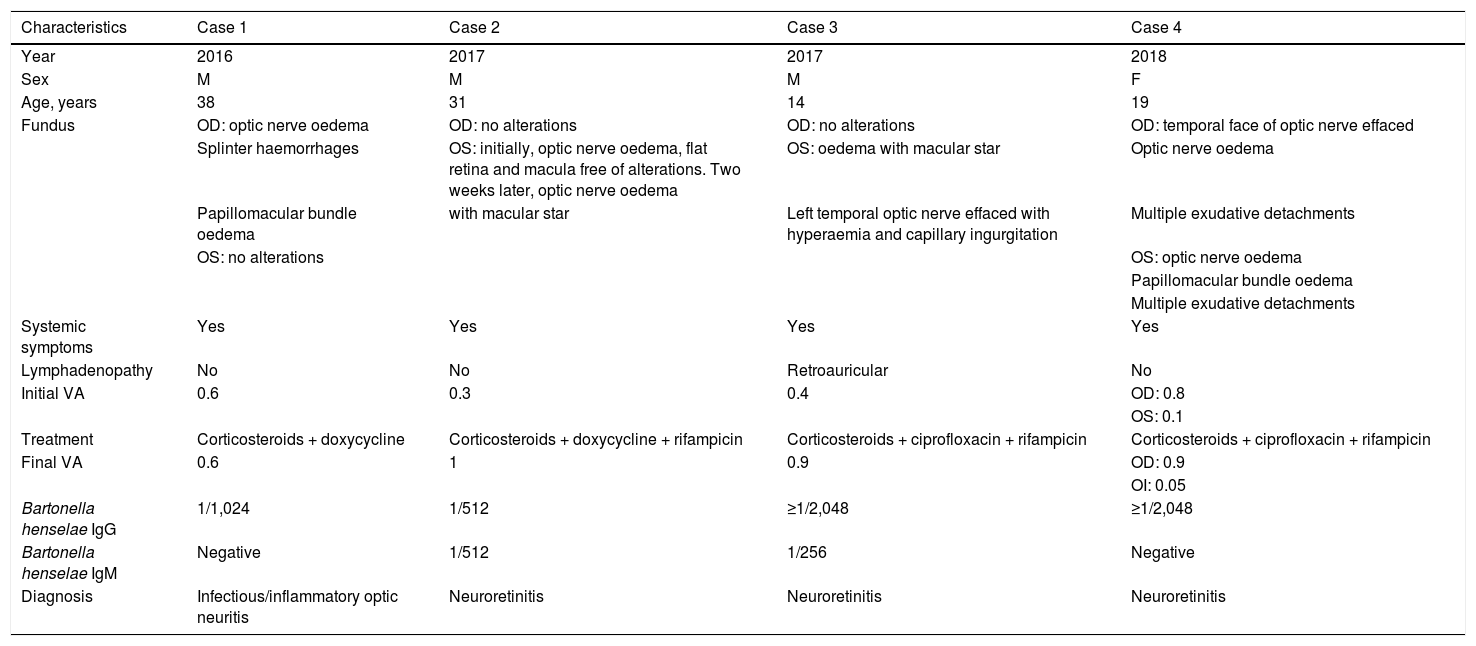

ResultsSeventy-four patients presented with CSD, four of which had involvement of the posterior segment of the eye (6.3%), one with infectious/inflammatory optic neuritis and three with neuroretinitis. Their demographic, clinical and serological characteristics, treatment and evolution can be seen in Table 1. Below is a brief description of each case.

Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, treatment and clinical course.

| Characteristics | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Sex | M | M | M | F |

| Age, years | 38 | 31 | 14 | 19 |

| Fundus | OD: optic nerve oedema | OD: no alterations | OD: no alterations | OD: temporal face of optic nerve effaced |

| Splinter haemorrhages | OS: initially, optic nerve oedema, flat retina and macula free of alterations. Two weeks later, optic nerve oedema | OS: oedema with macular star | Optic nerve oedema | |

| Papillomacular bundle oedema | with macular star | Left temporal optic nerve effaced with hyperaemia and capillary ingurgitation | Multiple exudative detachments | |

| OS: no alterations | OS: optic nerve oedema | |||

| Papillomacular bundle oedema | ||||

| Multiple exudative detachments | ||||

| Systemic symptoms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lymphadenopathy | No | No | Retroauricular | No |

| Initial VA | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 | OD: 0.8 |

| OS: 0.1 | ||||

| Treatment | Corticosteroids + doxycycline | Corticosteroids + doxycycline + rifampicin | Corticosteroids + ciprofloxacin + rifampicin | Corticosteroids + ciprofloxacin + rifampicin |

| Final VA | 0.6 | 1 | 0.9 | OD: 0.9 |

| OI: 0.05 | ||||

| Bartonella henselae IgG | 1/1,024 | 1/512 | ≥1/2,048 | ≥1/2,048 |

| Bartonella henselae IgM | Negative | 1/512 | 1/256 | Negative |

| Diagnosis | Infectious/inflammatory optic neuritis | Neuroretinitis | Neuroretinitis | Neuroretinitis |

M: male; F: female; OD: right eye; OS: left eye; VA: visual acuity.

A 38-year-old man who, after three days of general malaise, myalgia and cough, presented sudden loss of vision in the lower field of his right eye (OD), reporting a clear horizontal level in half his field of vision. He worked in a rural setting with frequent contact with cats. At the time he presented IgG against B. henselae of 1/1,024 and negative IgM, with the IgG titre dropping to 1/128 five months later. He was diagnosed with infectious/inflammatory optic neuritis and treated with corticosteroids and doxycycline for six weeks. At discharge, nine months later, his visual acuity of OD remained reduced (0.6).

Case 2A 31-year-old man who attended the Emergency Department after one week of fever, frontal and temporal headache with dysesthesia in that area, and blurred vision and pain in his left eye (OS). He owned a cat, which had scratched him multiple times. He presented IgG and IgM against B. henselae at a titre of 1/512. Diagnosed with neuroretinitis, he was treated with corticosteroids in combination with doxycycline and rifampicin for six weeks. At discharge, nine months later, his acuity of OS was 1.0.

Case 3A 14-year-old boy who attended the Emergency Department after one week of fever, headache, odynophagia and loss of visual acuity in OS, which he described as “the presence of black spots”. He owned several cats, including kittens. He presented specific IgG ≥1/2,048 and IgM 1/256, with the titres reducing two weeks later to 1/512 and <1/64, respectively. The patient was diagnosed with neuroretinitis and treated with corticosteroids in combination with ciprofloxacin and rifampicin for six weeks. At discharge, two months later, his visual acuity of OS was 0.9.

Case 4A 19-year-old woman with visual disturbances over several days, such as dispersed scotomas and object deformities in OS, accompanied by an oppressive holocranial headache that was predominantly retro-ocular in OS. The loss of vision was worsening and became bilateral. She had frequent contact with a cat, which had scratched her multiple times. She presented IgG against B. henselae ≥1/1,024 and negative IgM; 12 weeks later, IgG was 1/256. Diagnosed with neuroretinitis, she was treated with corticosteroids in combination with ciprofloxacin and rifampicin for six weeks. At discharge, one year later, she presented visual acuity of 0.9 in OD and 0.05 in OS and optic atrophy in the temporal side of OS.

DiscussionIn the literature, ocular involvement has been described in 5–10% of patients with CSD, mostly in the form of Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, and in a lower proportion in the form of other atypical manifestations, including neuroretinitis1,5. In this review, four patients (6.3%) presented involvement of the posterior segment of the eye with a history of contact with cats, three in the form of neuroretinitis and one as infectious/inflammatory optic neuritis.

Neuroretinitis in patients with CSD was first described by Sweeny and Drance in 19706 and is considered the most common complication of B. henselae infection involving the posterior segment of the eye5,7. It is a syndrome of loss of visual acuity due to optic nerve oedema associated with macular exudates, typically in a star-shaped pattern2,8, which was observed in two of the patients with neuroretinitis in this study (cases 2 and 3, Table 1).

Clinically, neuroretinitis manifests as a sudden loss of visual acuity, generally unilaterally1,2,4, often preceded by influenza-like symptoms1. All four patients in this study reported previous non-specific symptoms (fever, headache, general malaise and/or myalgia), with the ocular involvement being unilateral in three of them. However, bilateral involvement is not uncommon, as is reported in the review by Ksiaa et al. (54.1%)8. Regional lymphadenopathy, a typical characteristic of CSD, is less common in involvement of the posterior segment of the eye: Habot-Wilner et al. described it in 20% of their patients4. In this series, the presence of retroauricular lymphadenopathy was observed in one patient.

The diagnosis of ocular CSD is based on characteristic clinical findings, history of contact with cats and serology indicative of recent infection with B. henselae (positive IgM and/or IgG ≥1/256)8. The four cases presented here had positive serology results (all IgG ≥1/512 and two IgM ≥1/256). It is common in the context of CSD for IgM not to be detected because the disease is subacute (patients may be treated late in its course) and because IgM in B. henselae infections is short-lived2.

Doxycycline, rifampicin, macrolides or fluoroquinolones, usually in combinations of two antibiotics, are generally recommended for the treatment of neuroretinitis1. In the latest revision of UpToDate9, combined antibiotic treatment associated with corticosteroids is recommended for all patients with neuroretinitis secondary to CSD, doxycycline and rifampicin in patients over eight years of age, and azithromycin or trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole plus rifampicin in those younger than eight. There is no consensus on the optimal duration of treatment, but it has been recommended to maintain it for at least six weeks9.

While ocular involvement due to CSD can resolve spontaneously with a favourable visual prognosis in immunocompetent patients1,8, it is not uncommon for vision loss to persist, as has been observed in 6–13.5% of cases in some reviews4,7. Close ophthalmological follow-up is therefore important in these patients. Two of the patients in this study presented a unilateral loss of visual acuity at discharge despite the prolonged antibiotic treatment: the patient with infectious/inflammatory optic neuritis presented a visual acuity of 0.6 in OD and one of the patients with neuroretinitis 0.05 in OS.

In conclusion, involvement of the posterior segment of the eye is a complication of CSD that can sometimes have serious sequelae such as loss of visual acuity. This is of particular significance as CSD often affects young subjects (more potential years of cumulative disability). It is necessary to consider the possibility of B. henselae infection in any inflammatory involvement of the posterior segment of the eye so that specific treatment can be started as early as possible.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Salicio-Bermejo Y, Cilla-Eguiluz G, Blanco-Esteban A, Martin-Peñaranda T, Grandioso-Vas D, Echeverría-Irigoyen MJ. Neurorretinitis por Bartonella henselae en Gipuzkoa, 2014−2019. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:451–453.