In a recent report, Salazar Alarcón et al.1 described a case of lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis (LAR) caused by Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae (R. sibirica mongolotimonae), with no cases in the pediatric population previously reported in the literature. In this letter, we report another pediatric case of LAR by R. sibirica mongolitimonae in southern Spain, which confirms an expanded distribution of this agent in our country. Moreover, we aim to highlight the potential risks associated with its main vector, the species of the genus Hyalomma.2 Human transmission by Hyalomma ticks of other life-threatening zoonotic agents such as Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) has already been reported.3

We report the case of a 4-year-old boy with fever of up to 39.7°C for 5 days. In the 24h before the onset of fever, he presented a lesion compatible with a bite on the inner side of the right thigh. Physical examination revealed a circular lesion (5mm) with a necrotic eschar, surrounded by a slightly raised inflammatory halo (Fig. 1). He associated rope-like lymphangitis running from the eschar up to the inguinal region, where a painful adenopathy (2cm×1cm) was found. The rest of the physical examination was normal. A shave biopsy was performed to determine a Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Rickettsia. Analytical control was performed with blood count: 10,180 leukocytes (70.8% N, 16.4% L, 12.6% M); Red and platelet series, biochemical profile, and basic coagulation were normal. CRP 24.9mg/L. He began treatment with oral azithromycin and intravenous amoxicillin-clavulanate. Serological studies of Rickettsia conorii, Borrelia Burgdoferi, and Bartonella henselae were negative. He showed a favorable evolution and was discharged on the fifth day. Follow-up confirmed good evolution and no seroconversion. The diagnosis was confirmed with the results of PCR in the eschar sample performed at the National Center for Microbiology: PCR Borrelia sp. negative and positive for Rickettsia sibirica mongolotimonae. Bands compatible with Rickettsia (SFG) infection were detected, using as targets fragments of the ompA and ompB genes (conventional PCR), and 23S rRNA (real-time PCR). Definitive identification was obtained by molecular sequencing of ompA and ompB genes (491 and 464bp, respectively) that revealed 100% identity with Rickettsia sibirica subsp. mongolitimonae.

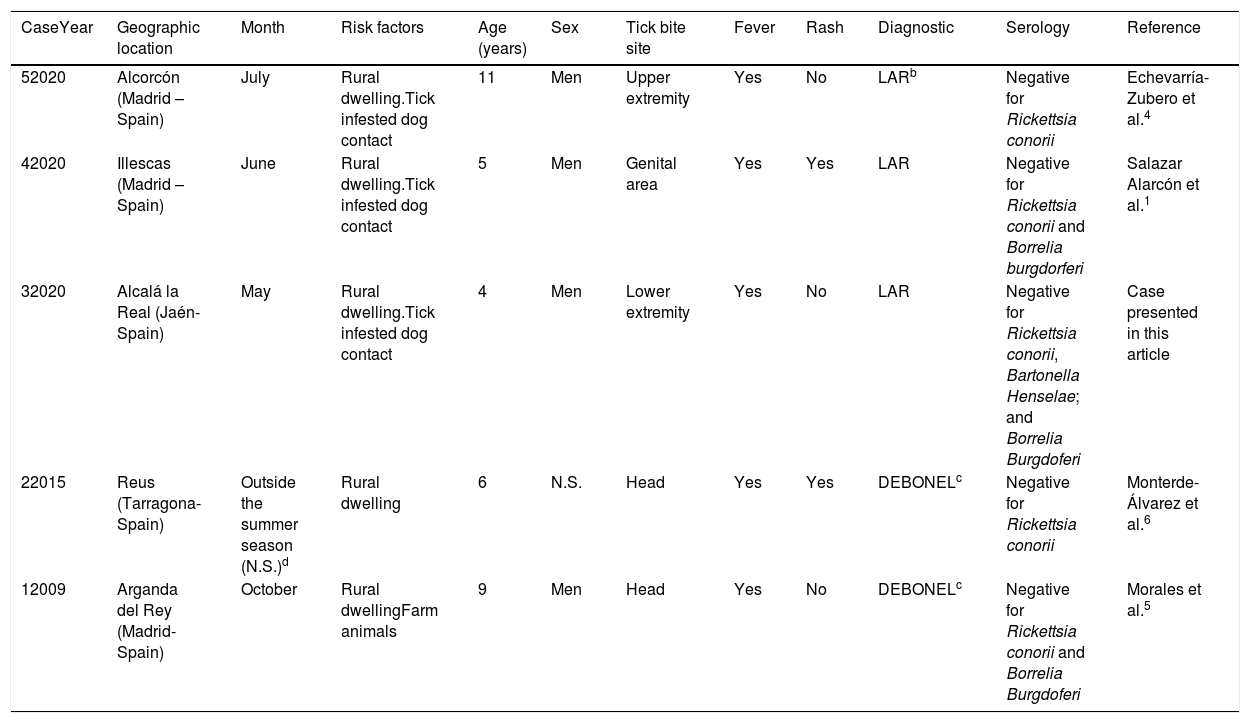

Different clinical manifestations of the infection have been described, such as Dermacentor-borne necrosis erythema and lymphadenopathy (DEBONEL) and mainly, lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis (LAR).2 The few reported cases of R. sibirica mongolotimonae infection in children1,4–6 are presented in Table 1. The median age of LAR cases was 5 y.o. The three of them were detected in late spring and early summer. In all cases fever was present and just one case presented a generalized skin rash. In the DEBONEL pictures, the presence of eschar and adenopathy also stands out, generally in the upper half of the body and scalp; fever may not always be present and usually occur in cold months.2 In adults, severe manifestations have been described,7 such as septic shock, acute kidney injury, myopericarditis, retinal vasculitis, and neurological alterations, including encephalitis, among others.

Infections by Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonaea in children.

| CaseYear | Geographic location | Month | Risk factors | Age (years) | Sex | Tick bite site | Fever | Rash | Diagnostic | Serology | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52020 | Alcorcón (Madrid – Spain) | July | Rural dwelling.Tick infested dog contact | 11 | Men | Upper extremity | Yes | No | LARb | Negative for Rickettsia conorii | Echevarría-Zubero et al.4 |

| 42020 | Illescas (Madrid – Spain) | June | Rural dwelling.Tick infested dog contact | 5 | Men | Genital area | Yes | Yes | LAR | Negative for Rickettsia conorii and Borrelia burgdorferi | Salazar Alarcón et al.1 |

| 32020 | Alcalá la Real (Jaén-Spain) | May | Rural dwelling.Tick infested dog contact | 4 | Men | Lower extremity | Yes | No | LAR | Negative for Rickettsia conorii, Bartonella Henselae; and Borrelia Burgdoferi | Case presented in this article |

| 22015 | Reus (Tarragona-Spain) | Outside the summer season (N.S.)d | Rural dwelling | 6 | N.S. | Head | Yes | Yes | DEBONELc | Negative for Rickettsia conorii | Monterde-Álvarez et al.6 |

| 12009 | Arganda del Rey (Madrid-Spain) | October | Rural dwellingFarm animals | 9 | Men | Head | Yes | No | DEBONELc | Negative for Rickettsia conorii and Borrelia Burgdoferi | Morales et al.5 |

In all cases, the diagnosis was confirmed with the results of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the biopsy of the eschar sample. DNA samples were tested by PCR targeting fragments of the rickettsial genes ompA and ompB (conventional PCR). Definitive identification was obtained by molecular sequence of ompA and ompB, what showed a 100% identity with Rickettsia sibirica subsp. Mongolitimonae.

One of the limitations in the study of these cases is the difficulty in identifying the species of tick involved, unknown as in our case. Nevertheless, although it has been isolated in Rhipicephalus pusillus and R. bursa, its main vector is considered to be the species of the genus Hyalomma.2 These species are characterized by their aggressive host-seeking behavior8 (unlike other ticks utilizing a passive ambush strategy as they wait in vegetation), at a surprising speed for its size.8 Perfectly adapted to semi-desert climates, they usually have maximum activity in the hot and dry months.8 They are not very anthropophilic, although, in Spain, a progressive increase in their population is reported3,9 along with a high proportion of CCHFV infected ticks collected from wildlife.3,9 The change in climatic conditions seems to play an important role in this increasement.9,10 The fragmentation of the plant habitat and the abandonment of farmland would also be also decisive in tick populations and their hosts, causing increased contact rates between humans and infected ticks.10 These potential risks emphasize the importance of the development of new prevention strategies and the evaluation of this threat to public health.3

Informed consentThe family of the patient described in this case report gave their informed consent for the inclusion in this publication.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest in this article.