Early and adequate treatment of bloodstream infections decreases patient morbidity and mortality. The objective is to develop a preliminary method for rapid antibiotic susceptibility testing (RAST) in enterobacteria with inducible chromosomal AmpC.

MethodsRAST was performed directly on spiked blood cultures of 49 enterobacteria with inducible chromosomal AmpC. Results were read at 4, 6 and 8h of incubation. Commercial broth microdilution was considered the reference method. Disks of 10 antibiotics were evaluated.

ResultsThe proportion of readable tests at 4h was 85%. All RAST could be read at 6 and 8h.

For most antibiotics, the S or R result at 4, 6 and 8h was greater than 80% after tentative breakpoints were established and Area of Technical Uncertainty was defined.

ConclusionsThis preliminary method seems to be of practical use, although it should be extended to adjust the breakpoints and differentiate them by species.

El tratamiento precoz y adecuado de las bacteriemias disminuye la morbilidad y mortalidad de los pacientes. El objetivo es desarrollar un método preliminar de pruebas rápidas de sensibilidad antibiótica (PRSA) en enterobacterias con AmpC cromosómica inducible.

MétodosLas PRSA se realizaron directamente de hemocultivos simulados positivos para 49 enterobacterias con AmpC cromosómica inducible. Los resultados se leyeron a las 4, 6 y 8 horas de incubación. La microdilución en caldo comercial se consideró el método de referencia. Se evaluaron discos de 10 antibióticos.

ResultadosLa proporción de pruebas legibles a las 4 horas fue del 85%. Todas las PRSA pudieron leerse a las 6 y 8 horas.

Para la mayoría de los antibióticos, el resultado S o R a las 4, 6 y 8 horas fue superior al 80%, después de que se establecieran puntos de corte provisionales y se definiera el área de incertidumbre técnica.

ConclusionesEste método preliminar parece ser de utilidad práctica, aunque debería ampliarse para ajustar los puntos de corte y diferenciar por especies.

Adequate early management of sepsis is imperative to decrease mortality and morbidity. Administration of correct antimicrobial therapy within the first hours of symptom onset increases the survival rate.1

Reliable and early information on antibiotic susceptibility allows early adjustment of treatment. The tests performed in laboratories for the determination of antibiotic susceptibility allow us to obtain results in 16–20h. Therefore, it is necessary to implement rapid antibiotic susceptibility testing (RAST), mainly in severe infections, which will allow us to shorten the time of the results.2

In 2019 the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) publishes a method of RAST performed directly from positive blood culture bottles. It is a simple method that allows results to be obtained between 4 and 8h. At present it has been validated for some bacterial species3 but no studies have been performed to develop RAST in enterobacteria with inducible chromosomal AmpC, prevalent in severe infections. Our objective is to develop a preliminary method for RAST in enterobacteria with inducible chromosomal AmpC.

Material and methodsTo simulate real conditions, BACTEC™ Plus Aerobic/F blood culture bottles (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks MD, USA), were inoculated with 5ml of human blood and 1ml of a solution with 100–200CFU/ml, which was previously prepared by diluting a 0.5 McFarland suspension of each bacterial isolate 1/1,000,000.4 They were incubated in the automated BACTEC FX system (Becton, Dickinson and Company), being positive for 7–15h.

The disk diffusion method was performed as described by the RAST EUCAST method.3 Blood culture broth was inoculated on a Müller-Hinton plate (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK), disks of the different antibiotics (piperacillin/tazobactam, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, tobramycin and amikacin) were placed and the plate was subsequently incubated at 35±2°C. Reading was performed at 4, 6 and 8h.

Simultaneously, a subculture was performed on blood agar, incubating the plate for 16–20h to subsequently confirm identification by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MICROFLEX LT/SH (Bruker Daltonics)) and determine antibiotic susceptibility by microdilution in broth, considered the reference method, using the MicroScan® WalkAway® automated system.

RAST were performed directly from spiked blood cultures of 12 Enterobacter cloacae, 12 Citrobacter freundii, 13 Klebsiella aerogenes and 12 Serratia marcescens. All strains came from blood cultures of patients preserved in our collection. Strains with different antibiotic susceptibility were chosen to establish the tentative breakpoints: inducible phenotype: 27 strains; derepressed phenotype: 10 strains; quinolone resistance: 16 strains; aminoglycoside resistance: 9 strains; ESBL production: 3 strains; carbapenem resistance: 9 strains.

The percentage of readable tests at 4, 6 and 8h was calculated.

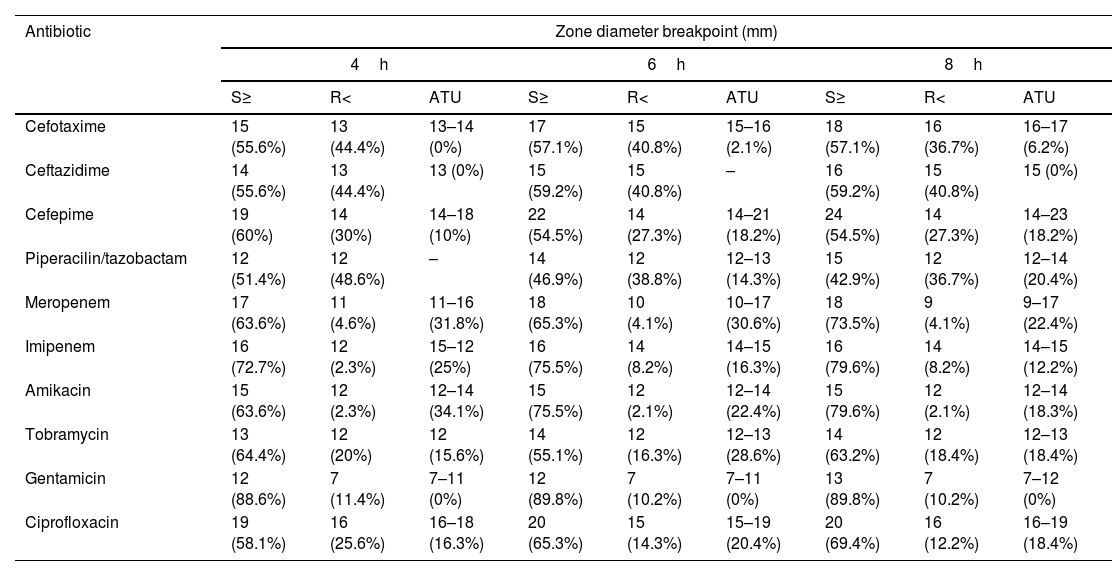

Tentative breakpoints were established for the inhibition zones at 4, 6 and 8h. For this purpose, we considered as a breakpoint of resistance in each time interval the inhibition zone with the largest diameter of the strains that were resistant with the reference method and as a breakpoint of susceptibility of each antibiotic the inhibition zone with the smallest diameter of the strains considered susceptible with the reference method. In some antibiotics the overlap between S and R isolates was problematic, we introduced Area of Technical Uncertainty (ATU), considering as such the diameter zones between both breakpoints.

ResultsThe proportion of readable tests at 4h of incubation was 85%. All RAST could be read at 6 and 8h.

When tentative breakpoints and ATU were established, as described in section “Material and methods”, the results shown in Table 1 were obtained. For most antibiotics, an S or R result at 4, 6 and 8h greater than 80% was obtained. The percentage of strains included in the ATU category ranged from 0% for gentamicin and ceftazidime at all time intervals to 34% for amikacin at 4h.

Breakpoints and ATU established at each incubation time interval and percentage of strains included in each category.

| Antibiotic | Zone diameter breakpoint (mm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4h | 6h | 8h | |||||||

| S≥ | R< | ATU | S≥ | R< | ATU | S≥ | R< | ATU | |

| Cefotaxime | 15 (55.6%) | 13 (44.4%) | 13–14 (0%) | 17 (57.1%) | 15 (40.8%) | 15–16 (2.1%) | 18 (57.1%) | 16 (36.7%) | 16–17 (6.2%) |

| Ceftazidime | 14 (55.6%) | 13 (44.4%) | 13 (0%) | 15 (59.2%) | 15 (40.8%) | – | 16 (59.2%) | 15 (40.8%) | 15 (0%) |

| Cefepime | 19 (60%) | 14 (30%) | 14–18 (10%) | 22 (54.5%) | 14 (27.3%) | 14–21 (18.2%) | 24 (54.5%) | 14 (27.3%) | 14–23 (18.2%) |

| Piperacilin/tazobactam | 12 (51.4%) | 12 (48.6%) | – | 14 (46.9%) | 12 (38.8%) | 12–13 (14.3%) | 15 (42.9%) | 12 (36.7%) | 12–14 (20.4%) |

| Meropenem | 17 (63.6%) | 11 (4.6%) | 11–16 (31.8%) | 18 (65.3%) | 10 (4.1%) | 10–17 (30.6%) | 18 (73.5%) | 9 (4.1%) | 9–17 (22.4%) |

| Imipenem | 16 (72.7%) | 12 (2.3%) | 15–12 (25%) | 16 (75.5%) | 14 (8.2%) | 14–15 (16.3%) | 16 (79.6%) | 14 (8.2%) | 14–15 (12.2%) |

| Amikacin | 15 (63.6%) | 12 (2.3%) | 12–14 (34.1%) | 15 (75.5%) | 12 (2.1%) | 12–14 (22.4%) | 15 (79.6%) | 12 (2.1%) | 12–14 (18.3%) |

| Tobramycin | 13 (64.4%) | 12 (20%) | 12 (15.6%) | 14 (55.1%) | 12 (16.3%) | 12–13 (28.6%) | 14 (63.2%) | 12 (18.4%) | 12–13 (18.4%) |

| Gentamicin | 12 (88.6%) | 7 (11.4%) | 7–11 (0%) | 12 (89.8%) | 7 (10.2%) | 7–11 (0%) | 13 (89.8%) | 7 (10.2%) | 7–12 (0%) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 19 (58.1%) | 16 (25.6%) | 16–18 (16.3%) | 20 (65.3%) | 15 (14.3%) | 15–19 (20.4%) | 20 (69.4%) | 16 (12.2%) | 16–19 (18.4%) |

ATU: Area of Technical Uncertainty; S: susceptible, standard dosing regimen; R: resistant.

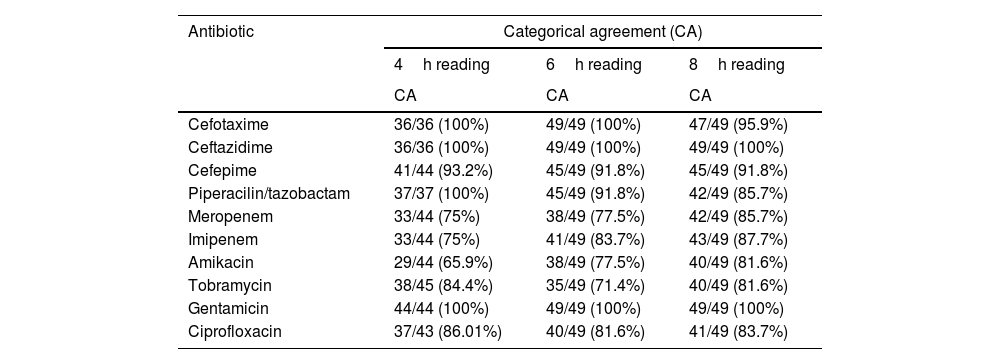

Categorical agreement at different incubation time intervals is shown in Table 2.

Results of antibiotic-bacteria categorical agreement at different incubation time intervals.

| Antibiotic | Categorical agreement (CA) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4h reading | 6h reading | 8h reading | |

| CA | CA | CA | |

| Cefotaxime | 36/36 (100%) | 49/49 (100%) | 47/49 (95.9%) |

| Ceftazidime | 36/36 (100%) | 49/49 (100%) | 49/49 (100%) |

| Cefepime | 41/44 (93.2%) | 45/49 (91.8%) | 45/49 (91.8%) |

| Piperacilin/tazobactam | 37/37 (100%) | 45/49 (91.8%) | 42/49 (85.7%) |

| Meropenem | 33/44 (75%) | 38/49 (77.5%) | 42/49 (85.7%) |

| Imipenem | 33/44 (75%) | 41/49 (83.7%) | 43/49 (87.7%) |

| Amikacin | 29/44 (65.9%) | 38/49 (77.5%) | 40/49 (81.6%) |

| Tobramycin | 38/45 (84.4%) | 35/49 (71.4%) | 40/49 (81.6%) |

| Gentamicin | 44/44 (100%) | 49/49 (100%) | 49/49 (100%) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 37/43 (86.01%) | 40/49 (81.6%) | 41/49 (83.7%) |

CA: categorical agreement.

It is important to shorten the period until effective therapy is administered in patients with severe illness; earlier results of antibiotic sensitivity testing may contribute to this.

RAST is a valuable and simple method to accelerate antimicrobial susceptibility testing and provide optimal antibiotic treatment for patients.

By modifying the breakpoints of the inhibition zone diameters at 4–8h as described in section “Material and methods” and defining the ATU category, we eliminate errors, leaving a percentage of susceptible and resistant strains that depends on each antibiotic and the reading time. Since for most antibiotics an S or R result at 4, 6 and 8h greater than 80% is obtained, it is, in our opinion, of practical use.

Our method developed on enterobacteria with inducible chromosomal AmpC directly from positive BC flasks provides results in one standard working day. It is uncomplicated to perform and requires only equipment and skills already available in clinical laboratories.

With the tentative breakpoints and ATU that were defined in this study, there are no errors.

But there are limitations: not all results were available within 4h, a relatively low number of strains have been used and no differentiation between species has been made.

Therefore, we consider the breakpoints defined to be preliminary. The study would have to be extended in the future to adjust the breakpoints. In addition, it would be desirable to differentiate them by species and to decrease the ATU intervals, thus increasing the values interpreted as S or R.

FundingNo funding has been received for this work.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest.