A 31-year-old male was admitted with unhealing left thumb lesions for years, cough, sputum, moderate fever, and night sweating. He admitted several times to health care for these lesions and used many antibiotics, but there was no response to all treatments. His physical examination was unremarkable except hyperkeratotic papules measuring 25mm×13mm on his left thumb (Fig. 1). Laboratory studies revealed the following: hemoglobin 14g/dL, hematocrit 42%, leukocytes 9800/mm3, platelets 504000/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 65mm/h, and CRP 60mg/L (normal range: 0–5). Other biochemical tests and urinalysis remained normal. Serologies for syphilis, Brucellosis, Hepatitis B Virus, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Epstein-Barr Virus, Toxoplasmosis, and Cytomegalovirus were unremarkable.

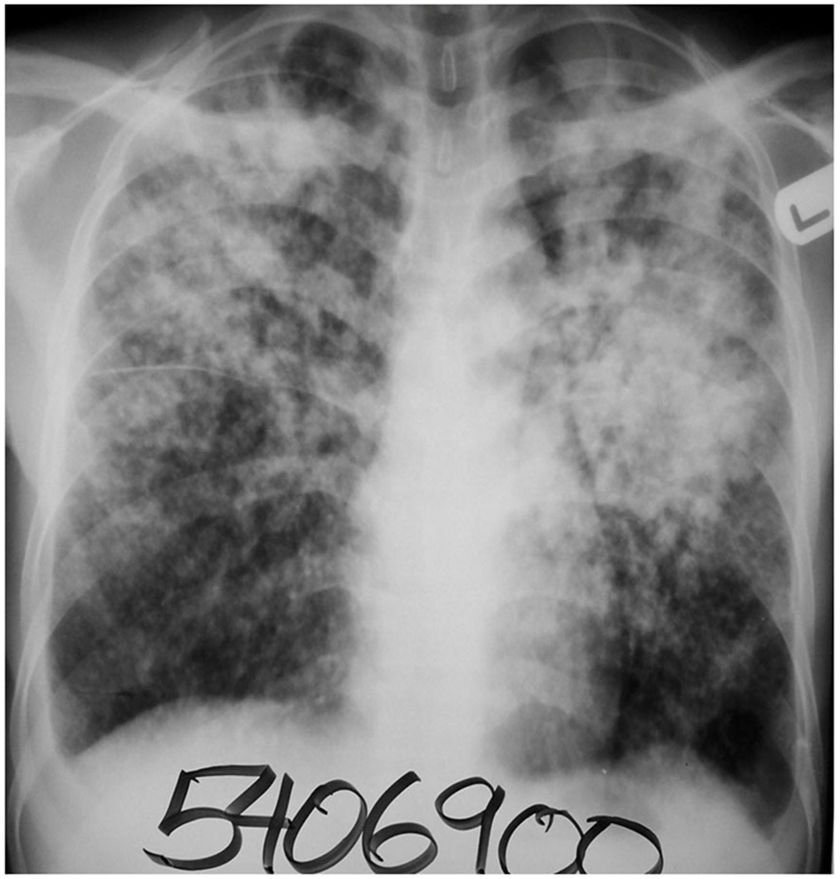

Diagnosis and evolutionIn the detailed medical history, he was diagnosed with pulmonary TB but treated inadequately. Plain chest X-ray revealed bilateral heterogeneous infiltrations on superior and middle zones (Fig. 2). Tuberculin skin test was positive (an induration of 30mm). Both sputum and fine-needle aspirate of the left thumb lesions revealed acid-fast bacilli. Both samples yielded Mycobacterium tuberculosis by Lowenstein-Jensen and MGIT media. Anti-TB drug susceptibility test was not studied in the case. Skin biopsy revealed a granulomatous dermatitis. The patient was diagnosed as having skin TB secondary to pulmonary TB (autoinoculation from mouth to hand while coughing, since he was using left hand to try to cover his mouth). The patient was treated successfully with the traditional regimen (intensive phase: 2 months and maintenance phase: 4 months). His symptoms of cough, sputum production and night sweating and cutaneous lesions improved within the first 2 months. Sputum remained negative for the bacilli in 3th month of therapy and pulmonary lesions healed over time. He was doing well 24 months after the end of therapy.

The patient was diagnosed with the chronic skin lesion as cutaneous TB based on microbiological and histopathological examinations of the materials (fine-needle aspirate and tissue biopsy). The patient who was a cobbler and his left thumb was frequently scratched due to occupational trauma. He stated to cover his mouth generally with his left hand, while coughing. We considered that the large amount of bacilli inoculated the skin during coughing, ultimately developing an infection. Thus, the diagnosis was post-primary autoinoculation TB (warty TB).

Similar to TB chancre, TB verrucosa cutis is considered as exogenous TB, based on the mechanism of development.1,2 In both clinical situations, bacilli are inoculated into skin directly from the environment. TB chancre develops through traumatic inoculation of sputum expelled by someone else (primary inoculation), while TB verrucosa cutis may develop by autoinoculation of one's own sputum (post-primary inoculation). Warty TB is frequently encountered in adult males. Even physicians may develop this disease through occupational exposure. Lesions can be seen on hands, wrists, dorsal surfaces of feet, knees, ankles, and gluteal regions.3,4 They are more common on the hands of adults and legs of children. Initial lesion of warty TB is a papule or papulopustule reddish brown or violet in color. Wart spreads peripherally until it becomes a plaque. Alternatively, a uniform, papillomatous plaque can develop. Normally, there is no lymphadenopathy, without secondarily infected. While the initial lesion can heal spontaneously within years, leaving behind atrophic scars, it can also progress slowly. This disease is encountered in individuals with a well or moderate functioning immune system and a positive tuberculin skin test as in the present case.

Cutaneous lesions are frequently caused by some infections such as mycobacteria (M. tuberculosis complex and nontuberculous mycobacteria), fungi (Madurella mycetomatis), bacteria (Nocardia spp.), and parasites (Leishmania spp.). These are often signs of localized or disseminated disease. The appearance of skin lesions may be pathognomonic but is often nonspecific. Therefore, skin biopsy is essential for definitive diagnosis. Microscopic, culture and histopathological examinations of tissue samples should be performed. TB cutis miliaris disseminata often occurs as a complication of acute miliary TB, which develops in patients with severe cellular immunodeficiency, such as advanced AIDS.5 Most patients with acute miliary TB do not exhibit cutaneous lesions. Tuberculosis cutis orificialis is a rare form of cutaneous TB and is due to the autoinoculation of mucocutaneous tissues from a visceral site of infection such as the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, or genitourinary tract.6 This rare type of cutaneous TB is observed on the nasal, oral, or anogenital skin or mucosa and is clinically significant to consider in individuals with periorificial nonhealing ulcers. Scrofuloderma results from the direct extension of the infection from a deep structure (e.g., lymph node, bone, joint, or epididymis) into the overlying skin.6 The neck, axillae, and groin are often involved, with the cervical lymph nodes as the most common source of infection. Lupus vulgaris is a chronic paucibacillary form of cutaneous TB that represents a reactivation of TB infection.6 It may occur due to direct extension from an underlying focus of infection or via hematogenous spread. Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are a group of bacteria naturally found in soil, water and dust and the incidence of their skin diseases is increasing.7 Their skin infections develop after trauma, surgery, or a cosmetic procedure. Skin lesion includes abscesses, nodules, or ulcers but may not be distinctive. A high index of suspicion is required in order to make the diagnosis. Tuberculids (such as erythema induratum of Bazin) are commonly considered cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction to M. tuberculosis antigens in patients with moderate or high immunity against the tubercle bacillus 8. Tuberculids are a group of dermatoses that tubercle bacilli cannot be isolated from the skin lesions. Cutaneous nocardiosis presents either as a part of disseminated infection or as a primary infection resulting from inoculation into the skin.9 In immunocompromised patients, its involvement is usually systemic, often with lung involvement. Three clinical variants have been identified and it frequently presents as a localized nodular process (actinomycetoma). Cutaneous leishmaniosis is the most common form and causes skin lesions, mainly painless ulcers, on exposed parts of the body. The agent is a phlebotomine sand fly and face, neck, and extremities are commonly affected.10

In conclusion, TB can present with a wide range of clinical entity. Skin TB should be included in the differential diagnosis of skin lesions, which have subacute/chronic clinical progression and do not respond to antibiotics.

Conflict of interestThere is no conflict of interest.