This was a 24-year-old Senegalese male, who had been living in Spain for nine months. Five months earlier, he reported pneumonia without an aetiological diagnosis, a 20 mm reaction to a Mantoux intradermal test, and was diagnosed as an inactive carrier of the hepatitis B virus.

The current condition began eight weeks earlier, with progressively worsening pain in his mid and lower back and weight loss of 4 kg, along with feeling hot and cold. As part of his previous medical history, he reported occasional self-limiting episodes of haematuria. There were no findings of interest from the physical examination, except for reduced mobility in the thoracolumbar region secondary to pain. Blood tests showed an increase in acute phase reactants with C-reactive protein 6.53 mg/dl, haemoglobin 12.7 g/dl, leucocytes 9.28 × 103/microlitre and eosinophils 7.3% (0.68 × 103/microlitre). Urinalysis showed moderate haematuria.

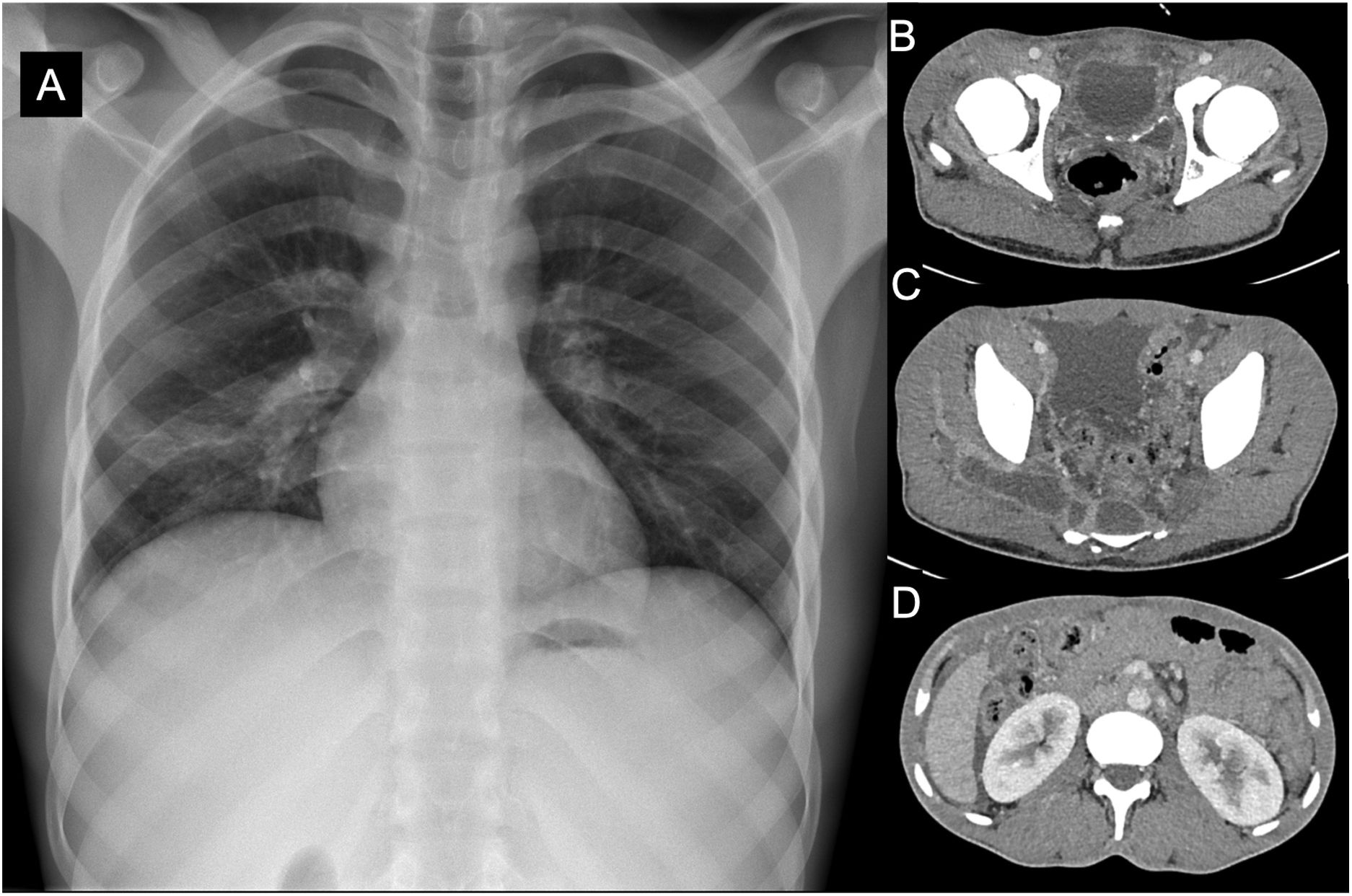

Chest x-ray (Fig. 1A) revealed an elevation of the right hemithorax and a slight ipsilateral infiltrate. Computed tomography of the abdomen (Fig. 1B, C and D) showed images suggestive of abdominal tuberculosis, along with collections of up to 14 cm in the presacral region, with extension to the gluteus medius with multiple areas of osteomyelitis. Cultures of bronchoalveolar lavage and gluteal abscess drainage samples were negative, including on Lowenstein-Jensen medium. However, the polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was positive. Sputum and urine cultures for mycobacteria were negative. He was started on treatment with antituberculosis drugs. The patient responded well, although he had a self-limiting episode of haematuria. Urine parasitology was requested. Microscopic study of the urinary sediment showed numerous long, oval eggs (110–170 μm long by 40–70 μm wide) with a terminal spur (Fig. 2) and miracidium larvae inside. The hatched eggs released the mobile miracidium larva, and the main structures such as the apical papilla and cilia could be seen (Appendix Bvideo).

A: chest x-ray showing elevation of the right hemithorax and a slight infiltrate in the right hemithorax. B, C and D: Computed tomography of the abdomen showing radiological findings suggestive of abdominal tuberculosis (multiple lymphadenopathy, peritoneal thickening, free fluid). Large lobulated abscess of up to 14 cm in the presacral region with extension to the gluteus medius. Areas of osteomyelitis.

Disseminated tuberculous with lung, bone, and gluteal involvement. Parasitic infestation by Schistosoma haematobium.

Closing remarksTuberculosis and schistosomiasis are prevalent infections in certain areas of the planet, usually associated with poor socioeconomic conditions with limited access to healthcare, and continue to be a major public health problem in some regions of the world.

It is possible that tuberculosis and schistosomiasis are mutual risk factors and that coinfection can significantly suppress the host immune system, increasing intolerance to antimicrobial therapy and being detrimental to the prognosis of the disease.

Although in the only large prospective study conducted to date, baseline helminth parasitic infection status had no effect on active pulmonary tuberculosis incidence rates or disease severity, this lack of correlation has not been definitively established.1

In Spain, testing for these two infections is particularly relevant in the context of providing care for immigrants, refugees and travellers from these regions. It is well known that tuberculosis acquired outside Europe is quite frequently extrapulmonary, and that it is not uncommon for patients to have a normal chest X-ray.2 We frequently come across patients with urogenital tuberculosis who have not been diagnosed in time because of the large number of false negatives due to the lack of acid-fast bacilli in urine or tissue samples and the false negatives of the specific polymerase chain reaction. It is therefore advisable that the culture be performed from concentrated morning urine and assuming that the mycobacterial culture may take several weeks to become positive. In our case, the microbiology results were repeatedly negative.

The other major disease that we should consider when studying apparently “sterile” haematuria in these groups is schistosomiasis; among other reasons, due to the latent symptoms patients can have for long periods of time and because of its high prevalence. Different studies in apparently healthy sub-Saharan Africans have found prevalences of 25%.3 One small point to make is that in southern Europe at least two native sources of Schistosoma haematobium have been described, one in Corsica (since 2014) and another recent one in Almería.

Parasitology confirmation is obtained by visualising helminth eggs in microfiltered urine (collected between 11.00 a.m. and 2.00 p.m. or over 24 h). We should stress that it is very rare to be able to visualise the miracidium larva in clinical samples (unless a viability test is performed), the most common being to see the egg expelled in the urine without its ovular membrane having ruptured. In these clinical conditions, different serology, molecular and even pathology techniques can be of great help.

In conclusion, the diagnosis and treatment of both diseases can be difficult and we need to have a high degree of clinical suspicion in environments where both diseases are common, as both conditions need to be adequately addressed and treated.